When the New York Times invented fast fashion A journey through the history of fast fashion

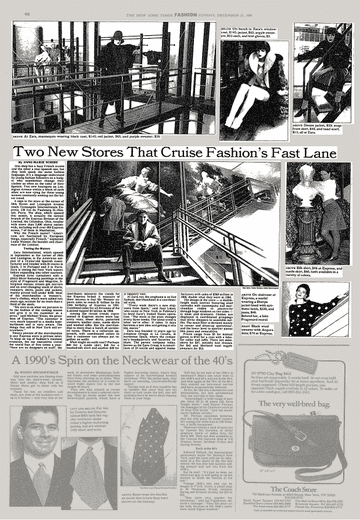

«Fashion: Two New Stores Go into Fashion's Fast Lane» was the headline of the New York Times on 31 December 1989 on the occasion of the opening of two new boutiques on Lexington Avenue, attracting the attention of «young women in constant search of the latest trend». On this occasion, the term "fast fashion" appeared for the first time, coined by journalist Anne-Marie Schiro to refer to a penchant for 'fast fashion' that had already emerged in the nineteenth century, but first conquered New York in the 1980s. Among the new openings mentioned was Zara International's first shop in the Big Apple, on the corner of 59th and Lexington, described at the time as "the American outpost of a Spanish manufacturer and retailer with 94 shops in Spain, 2 in Portugal and 2 in Paris" Prices ranged from $5 for knitted gloves to $145 for a coat with faux fur collar and cuffs, miniskirts for $27, metallic knit dresses for $43 and Shetland wool jumpers for $53. For the first time, less rich women were able to keep up with the trends, and it was on the basis of their unfulfilled desires that Zara laid the foundation for its success. But when was fast fashion really born and how did the meaning of the term evolve into the negative meaning we attach to it today?

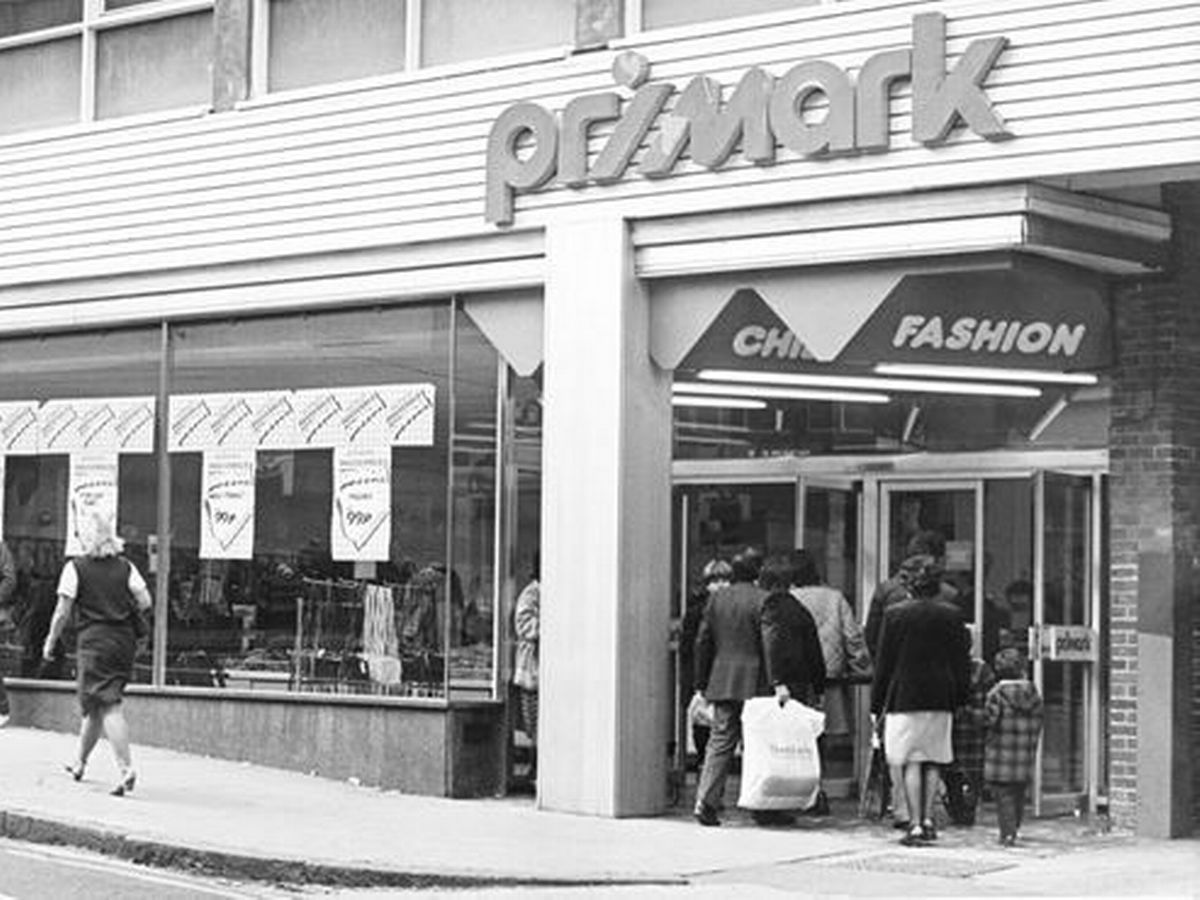

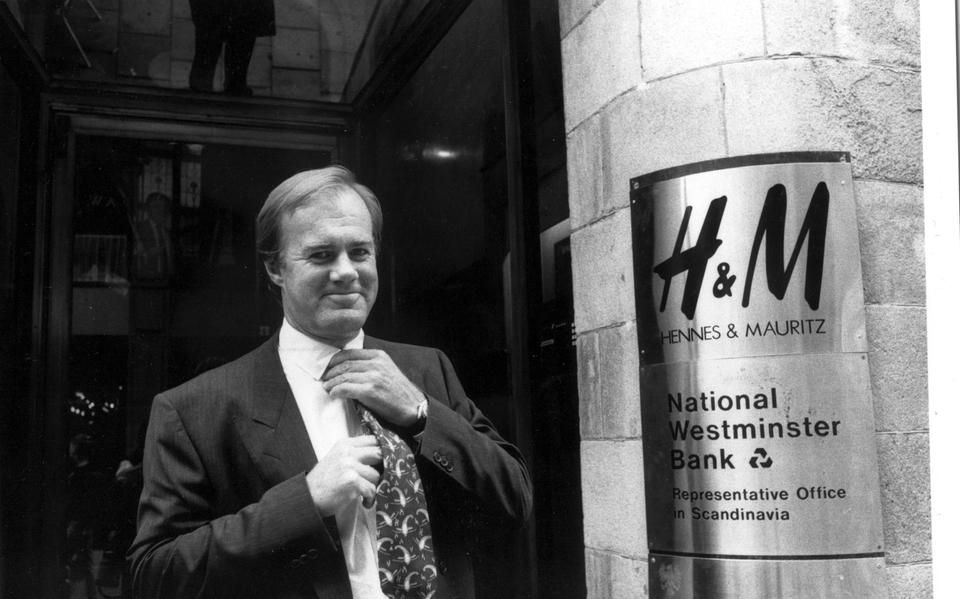

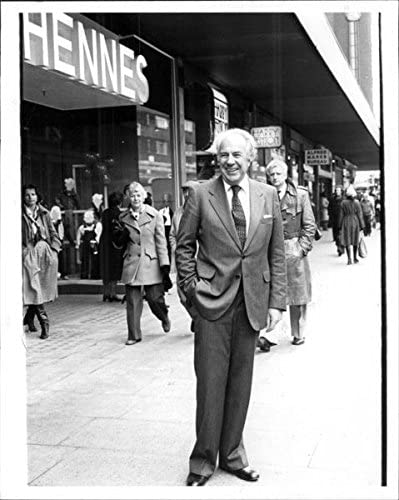

The Post points out that even if one cannot speak of 'fast fashion' for the nineteenth century, the textile industries established at that time still shape the way cheap clothes are made: «The first mass-produced garments - and they were for middle-class women, as the richer turned to tailors and the poorer sewed their own clothes - were partly made by people who worked at home for very little pay.» By the end of the Second World War, less affluent women and young people preferred to sew their clothes at home rather than rely on the neighbourhood tailor shop. The first shops dedicated to reproducing inexpensive Parisian designs opened, but the scale of the textile industry's production remained small. This changed in the 1950s when the big 'fast fashion' brands were born, most notably H&M, which was founded in 1947 when the Swede Erling Persson opened the shop 'Hennes' (which means 'their stuff' in Swedish) in the town of Vaesterås. The 'M' in the name was added twenty years later when Persson took over Mauritz Widforss' menswear boutique in 1968. Topshop and Primark followed in the 1960s, while Zara opened in La Coruñ in 1975 and was an immediate success. The Spanish giant applied the 'instant fashion' production model, where a team of designers created new clothes based on new trends in a very short time. The pace was so fast that it took the team only 15 days to design the top garment of the season, but costs remained low because the quality of materials and labour was lowered.

But even though fast fashion was initially hailed as a positive phenomenon in the democratization of fashion, aimed at making trends that had previously been the preserve of the wealthy few generally accessible, the weaknesses of an infrastructure that attempted to realise a utopia soon became apparent. The pace and cost of production, which accelerated year by year, could only be sustained if production took place in countries where labour costs were low and workers were more likely to be exploited. In the last two decades, spending little to dress fashionably has become commonplace, but only recently has the full extent of the problem of cheap fashion become clear. According to a United Nations report, the fashion industry causes 8 to 10% of all global CO2 emissions, i.e. between 4 and 5 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere every year, while investigation after investigation reports on the conditions of workers in large fast fashion companies, their struggle for minimum wages, job security and holidays, only to find that the situation has not improved in the slightest. Only last October, Channel 4's documentary, Untold: Inside the Shein Machine, denounced the conditions of workers at Shein, the Chinese counterpart to the historic fast fashion giants: many workers have no fixed salary and are paid 0.27 yuan CNY (50 cents) per garment produced, while the few who can show a regular contract earn a maximum of £500 per month for producing 500 garments per day. It is becoming increasingly obvious that cheap fashion actually comes at a very high price, but the workers and the environment are paying for it.