Dior's invisible strategy in the cinema world Masterpiece of "soft marketing" or randomness?

Everyone wonders how a haute couture atelier works. You often see pictures of Parisian studios where figures in white coats stand hunched over equally white tables as if they were in a surgical ward - and in many ways they are. Yet the subject of haute couture is not exactly popular in cinema: the last one worth mentioning is perhaps Phantom Thread, Paul Thomas Anderson's 2017 drama, where fashion actually played a fairly marginal role. And for the most part, fashion brands tend not to meddle too closely with film, merely providing support on the costume side, as Prada recently did with Elvis and Chanel with Spencer, but never lending their name or appearing directly. This kind of strategy was on full display with House of Gucci, a film with which the eponymous brand collaborated by providing archival looks, enjoying the media value brought in but without associating too closely with a film that, in fact, did not find huge success with critics. This kind of trend, however, was quietly subverted by Dior, which, in the same two-year period in which it transformed its historic Avenue Montaigne location into a giant concept store/museum, tangentally inserted itself into a cinematic storytelling that, without excessive risk, put the brand's history, craftsmanship and values in the spotlight. The films in question, released last year and this summer, respectively, are Haute Couture by Sylvie Ohayon and Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris by Anthony Fabian.

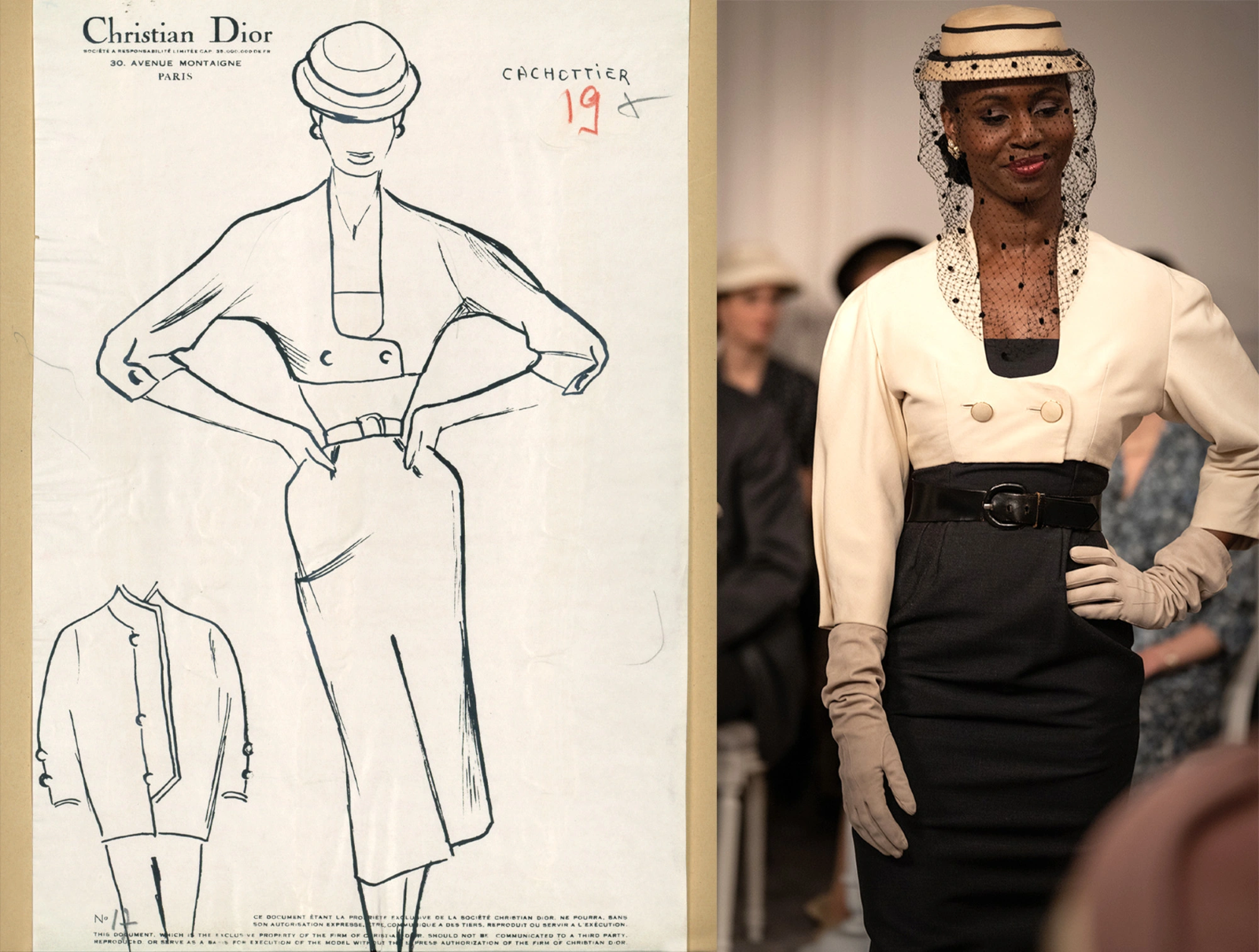

Although talking about different stories both films have several traits in common: both films are set in the Avenue Montaigne atelier (in the case of Haute Couture the location was not the real one and in the case of Mrs. Harris's it was an extremely faithful reconstruction), both films tell the story of the creation of haute couture gowns from the perspective of the brand's petit mains, both films were described by the press as "fairytales" (a fairytale of the creation of the gowns) and, indirectly, both constitute praise for the brand and the progressiveness of its values. In neither case, by the way, do the films appear to be marketing operations; they are two works that stand on their own two feet, yet it seems safe to assume that Dior's strategy with this kind of film collaboration represents a kind of experiment to test the ways in which a historic fashion brand can explicitly tell its story through an unusual medium without eroding its credibility.

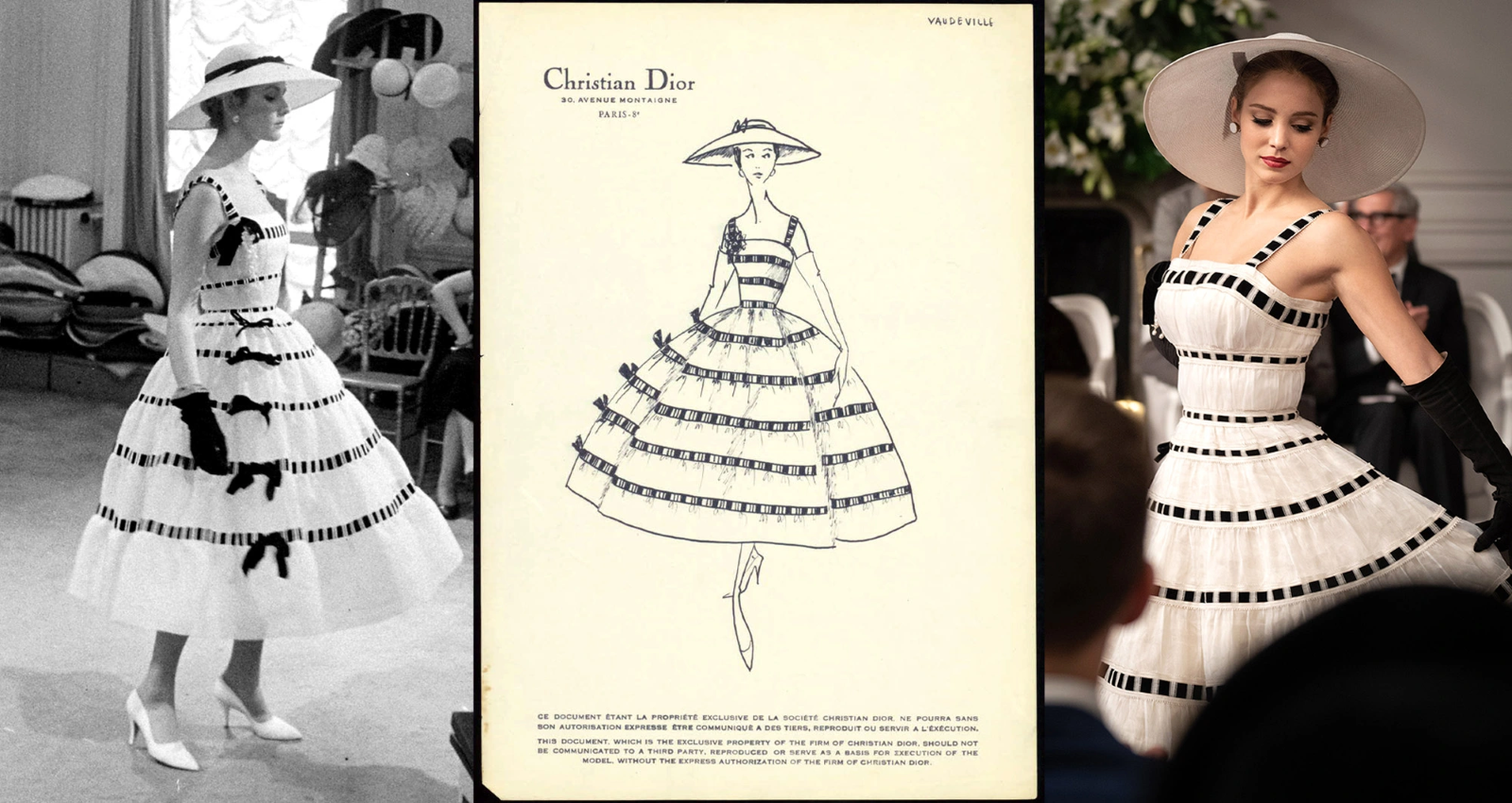

The ways of this strategy can be gleaned from the films themselves: discarding sensationalism, grand historical-biographical apparatuses and ostentatious glam and putting the spotlight on the work of the atelier and the professionals who populate it, telling stories from the everyday perspective of outsiders who approach the life of the brand with reverence, celebrating its myth and craftsmanship without ever lapsing into ultra-commercial flattery. Even the moment in Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris when an entire Dior Haute Couture show is reconstructed does not seem like rave praise but an affectionate and philologically correct tribute. Part of the strategy, and perhaps its winning element, was also the choice of productions, in both cases small and independent, without necessarily wanting to launch into huge-scale projects. When two different biographical films about Yves Saint-Laurent were released in 2014, for example, there was a huge confusion among viewers (the version we recommend is Bertrand Bonello's far more biting Saint Laurent) who went to see one film and practically forgot about the other which, by the way, because of the amount of sex and drug use in it, attracted the ire of Pierre Bergè himself.

And if the mistake of the Yves Saint Laurent biopics was to approach their subject in a manner that was now bland, now controversial, the Dior-centric films seen this year choose a narrative tone that circumvents the problem of how to tell the story of an icon, that is, without telling the story at all. In both films, Dior and the Avenue Montaigne atelier are the frame of the plot within which the story unfolds, not the subject, and because of this, the portrayal of the brand and its life appear in a naturally positive light.