The mystery of faith according to fashion Why the Church is the world's first brand

Although practising Catholics are an endangered species, the fascination exercised by ecclesiastical icons on the imagination of fashion designers has not lost its vital force. Catholic iconography is everywhere: from the rosaries, effigies of the Virgin Mary and ex-votos of flaming hearts that form the basis of D&G's stylistic identity and have defined Italianism in the eyes of the world for years, to Demna Gvasalia's monkish aesthetic in the FW21 campaign with Justin Bieber in a cassock, via Praying's more recent trinity slogans and Mowalola's papas. Whether the Holy Spirit manifests itself in an austere manner, recalling the unadorned imagery of the Franciscan monks with simple and mournful lines, or whether it takes the form of a Byzantine-inspired blaze of opulence, fashion has repeatedly drawn from the sacred dimension to create something very profane.

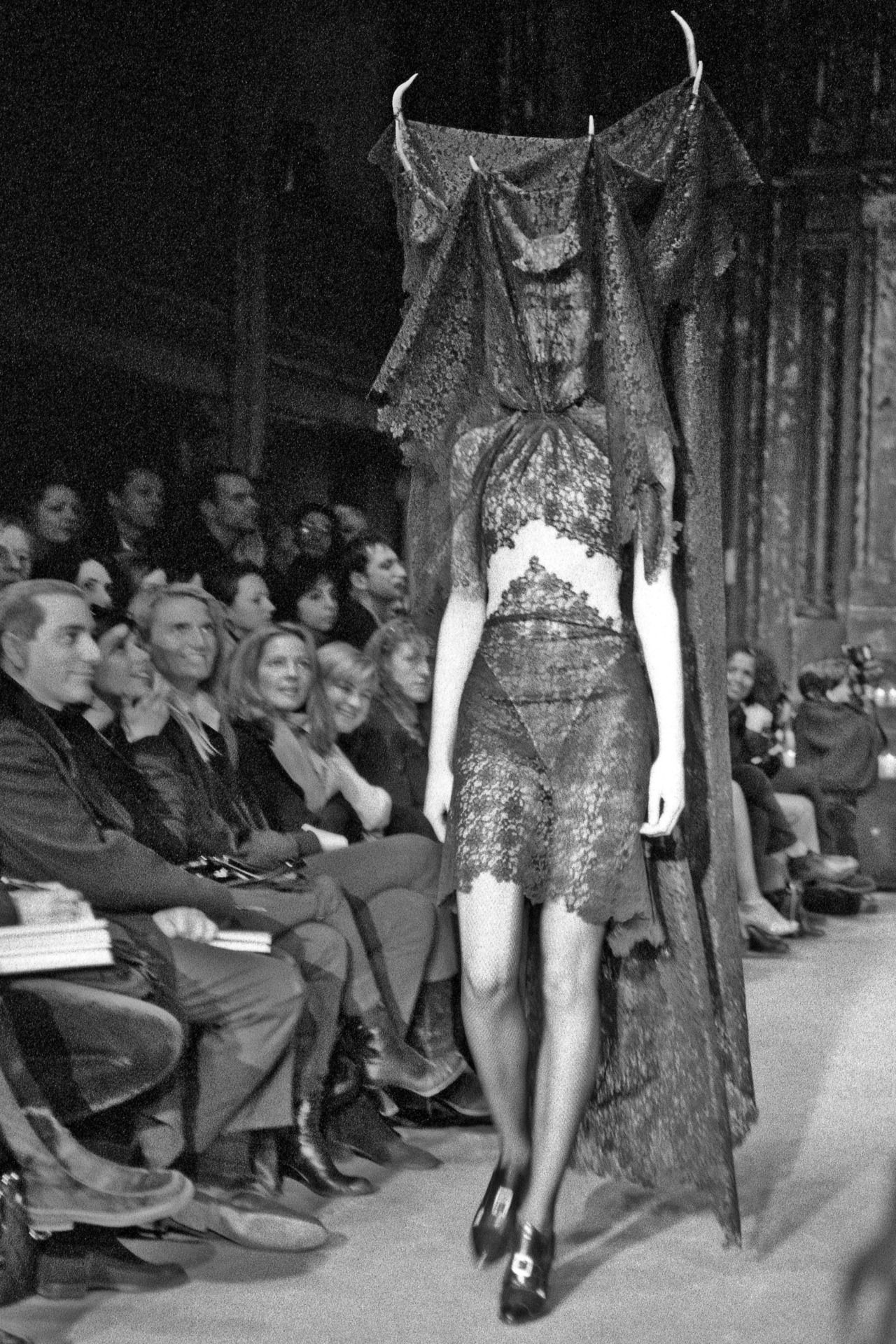

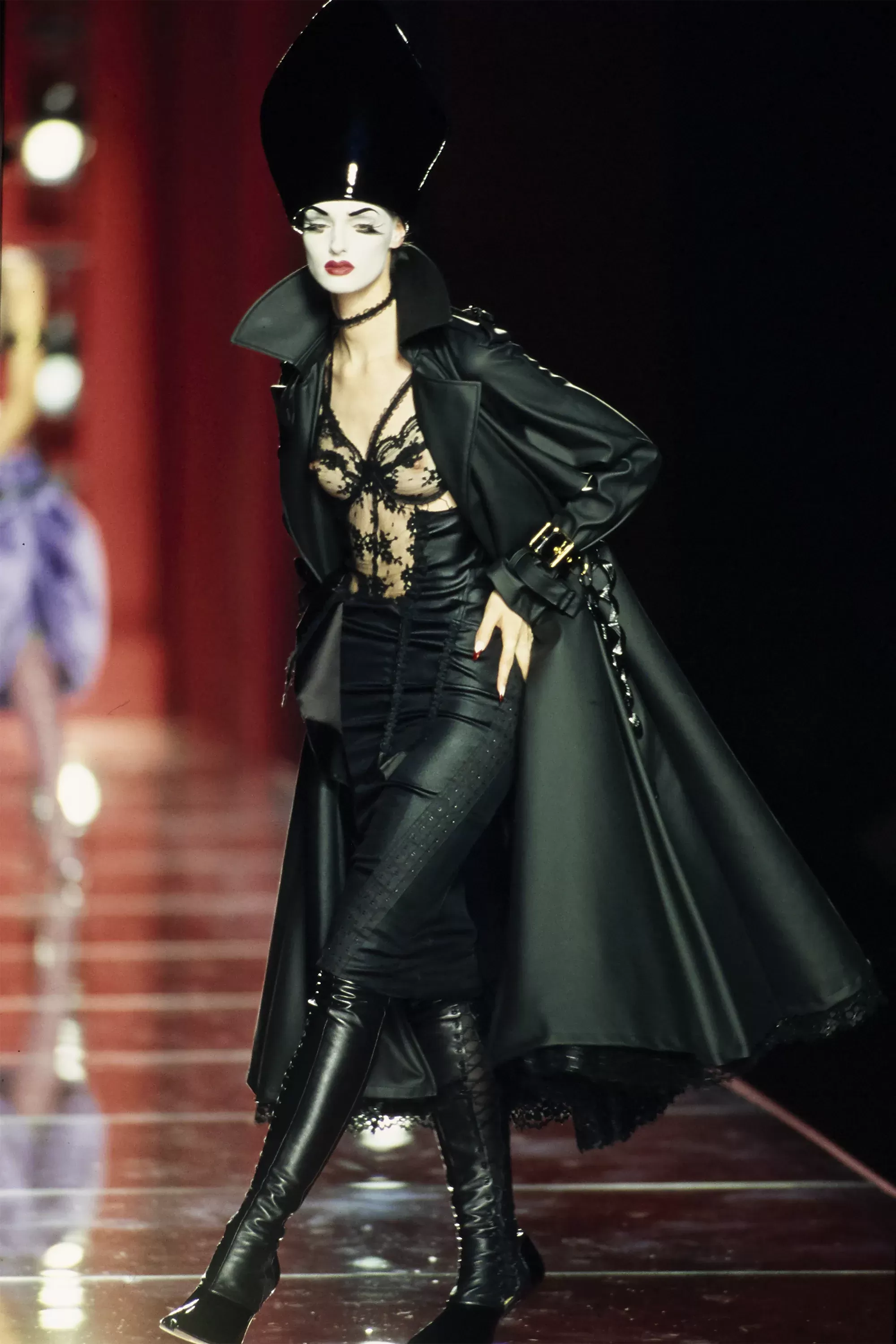

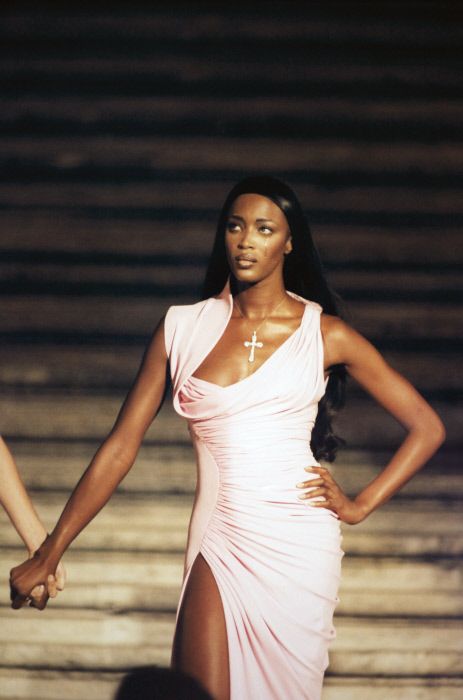

First, there are those designers who are (or have been) actually Catholic - Elsa Schiaparelli, John Galliano, Riccardo Tisci, Christian Lacroix, Coco Chanel, Jeanne Lanvin, Norman Norell or Thom Browne - and then there are those who have simply drawn inspiration from the mystery of faith, without taking part in it themselves. In 1996, set at Christ Church in Spitalfields, London, Alexander McQueen's 'Dante' collection featured a catwalk in the shape of a cross, an organ as soundtrack and models dressed in black lace veils and masks with a crucifix appliqué. One of the models wore McQueen's version of Jesus Christ's crown of thorns, an echo of Elsa Schiaparelli's 1938 collection entitled 'Pagan' and from which Tiffanny probably drew inspiration for the custom-made tiara intended for Kendrick Lamar. For Gaultier's SS07 couture, on the other hand, every woman on the catwalk was the embodiment of sanctity: haloes, faces painted like plaster statues, clothes inspired by devotional art. What looked like monastic hoods were actually stoles that descended in a train or lace commonly used to decorate shrines transformed into tight-fitting dresses. For Versace Couture FW97, however, a particular atmosphere turned inspiration into premonition, the show not only remaining in history because the garments were embellished with crosses, but also because it took place only a week before Gianni Versace's death. Givenchy under Riccardo Tisci was a triumph of biblical references: always a man of faith, the designer created a series of graphic prints on clothes for SS13, from the face of the Virgin Mary to the effigy of Christ, while the t-shirt with 'Jesus is Lord' written on it in 2010 became world famous.

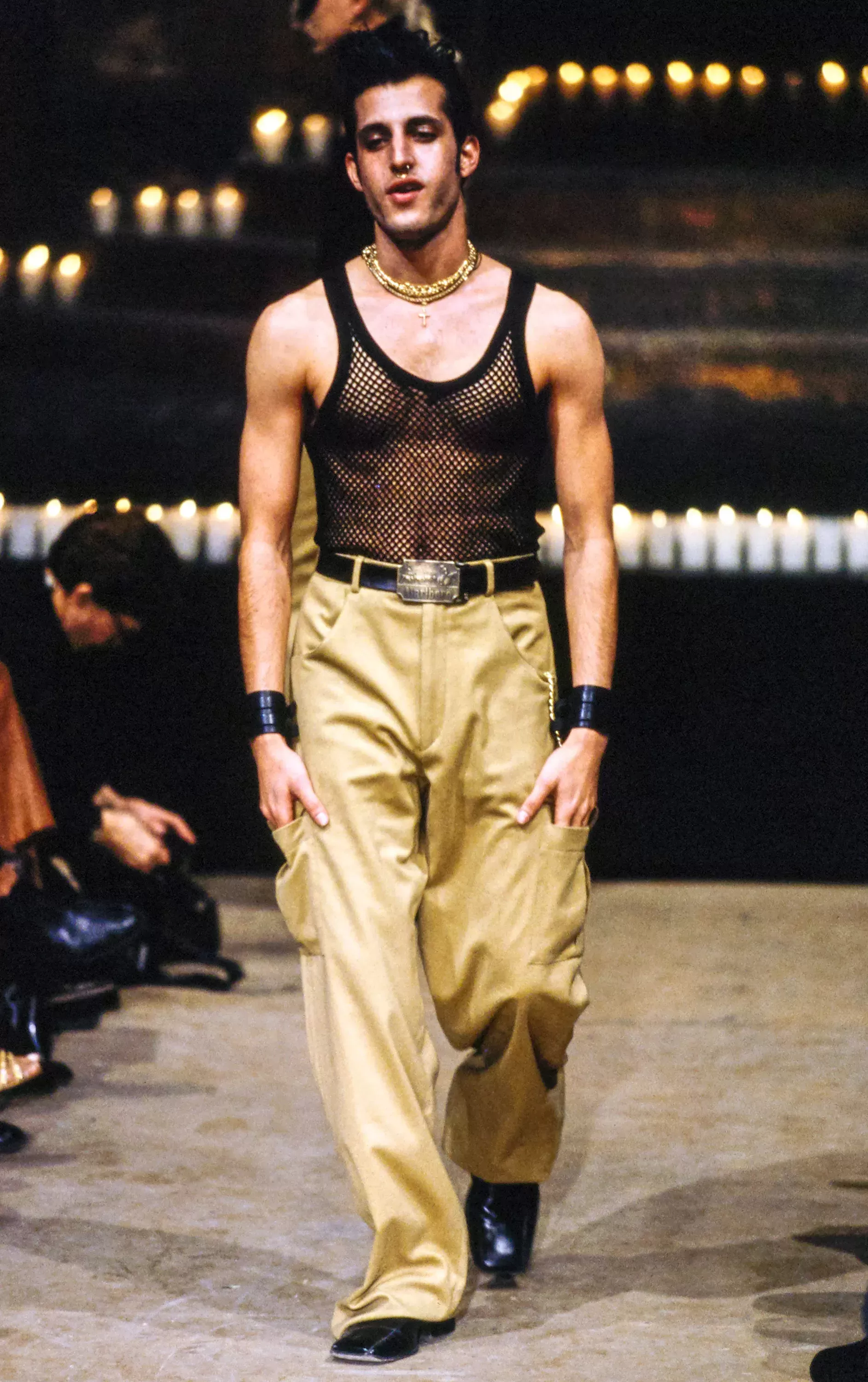

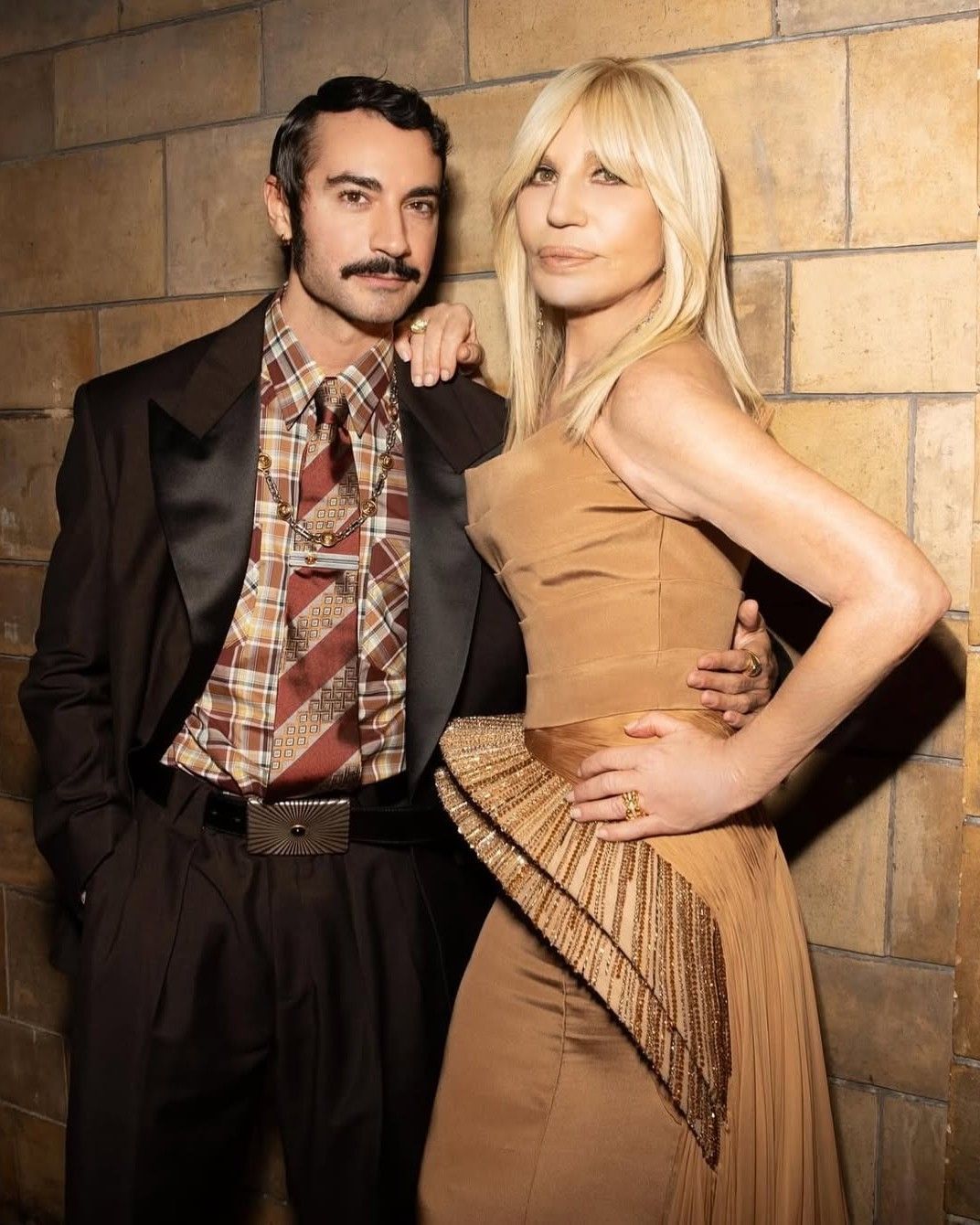

The church itself as a physical place was the illumination for the settings of several catwalks that attempted to reproduce scenes of devotion, including Thom Browne's AW13 where the smell of incense and a catwalk set up with wooden benches and kneelers and Gucci's runaways to the cloisters of Westminster and the cemetery of Arles. Not to mention all those archbishops, cardinals and pontiffs included, who despite a role that would impose abstention from a certain kind of interest in material goods, willingly or unwillingly have become true style icons, including Benedict XVI and his red velvet slippers, symbolic in his own words of martyrdom in the liturgical sense but rumoured to be by Prada. It was 1999 when Galliano showed a Catholic priest, who appeared on the catwalk looking particularly menacing, probably the result of some childhood trauma on the part of the designer. In 1939, Elsa Schiaparelli thought of decorating a dress with crossed keys (coat of arms of the Holy See), since then fashion has established a continuous dialogue with Catholicism made of symbols, cues and suggestions, which received its formal ennoblement at the 2018 Met Gala themed Heavenly Bodies, in which celebrities and designers explored and celebrated the theme (Zendaya as Joan of Arc, Alessandro Michele starring in a triptych with Jared Leto and Lana Del Rey, Rihanna as Papessa).

The ancestral link between clothing and religion could be reduced to a simple assumption: the fashion capitals, Paris and Milan, are historically Catholic. In the 1950s, Cristóbal Balenciaga Eizaguirre, a Spaniard by birth, inspired France with his garments that originated from the Catholic iconography he had grown up with: from the red drapes of papal robes to the opulent velvets of the Holy See. Since the beginning of time, human beings have questioned their existence, their nature, the meaning of things, without however finding an answer that goes beyond 'faith', the act of relying on a superior and supposed entity of whose existence there is no objective certainty. Since the 1st century, man has made up for the mystery that grips him by constructing a system of values and symbols that still today, despite being often controversial and anachronistic, influences our lives, from politics to society, passing through the wardrobe: the Church is the first brand ever created by man, perhaps with a little help from above.