Why dungarees never went out of fashion From the runways of Fashion Week to the closets of half the world

Never before has fashion been so experimental and contradictory, especially in menswear, as during these past two years - the watershed is almost without a doubt pandemic. While inches of exposed skin have left little to the imagination, there has been a revision of the classic bordering on austerity. In between is that delicate transition that saw the switch from the now casual, now tortured aesthetics and silhouettes of the 1990s to the decidedly lighter, skimpy silhouettes of the early 2000s. Crop tops, cut outs, low waists, but also the reappropriation of uniforms. Hence, for example, the reclamation of workwear elements such as dungarees.

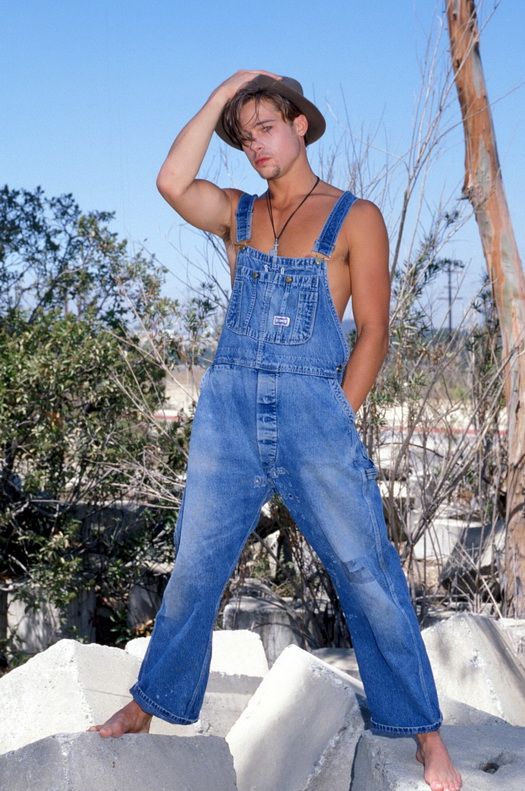

Originating in the late 18th century, dungarees were created as a utility garment, later becoming mass-produced by Levi Strauss in 1873. In the nearly 150 years since then, the garment has maintained its functional value associated with the work sphere, but simultaneously began to circulate within pop culture and fashion as an item for women and children. Lady Diana wore it, with that natural ease that allowed her to move from sportswear to revenge dress that made her even more appealing to the world press. It was also given a chance by actress Sarah Michelle Gellar, an icon of the 1990s, the ones in which dungarees were all the rage in TV series such as Friends, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air or Sex and the City, so much so that in 1994 the New York Times spoke of them as «fashion's best friend». Not that male celebrities have not made use of it: if a young as sexy Brad Pitt expressed the appeal of denim dungarees over leather, Chris Pine demonstrated much of its potential straddling utilty and coolness. Coolness that, inevitably, was eviscerated along the runways ridden by those brands and designers obsessed with the uniform theme.

Prada explored its design in the SS22 menswear collection, arriving at a decoding of the erotic and naïve that found an expressive line in white dungarees rolled up over the legs. Yet much of the aesthetic marked by dungarees draws on an imagery that is gorpcore. Gucci had launched an exclusive version in collaboration with The North Face, which sold out within a very short time. And, in all likelihood, those proposed by Dior Men with the SS23 collection will suffer the same fate: Kim Jones presented them in a color palette akin to the soft boy aesthetic, directing them toward a clearly genderless meaning. Quite different is the direction taken by JW Anderson who, with the SS22 show, tried to give voice to a narrative tension resulting from a reflection on masculinity: starting from the dictates of metrosexual aesthetics, the one more or less consciously beaten by soccer players such as David Beckham or Cristiano Ronaldo, Anderson deformed centimeters of fabric by making the garments "strange": his dungarees are short, tight and one-shouldered. Still different is Jacquemus's, which, in a surely less complicated key, has been tinged with fuchsia, glamour and marketability. If in fact in fashion it is possible to trace different families of brands, united by often overlapping scenarios, the same discourse can be extended to an item such as dungarees: depending on the brand of reference it is loaded with colors, meanings and fabrics that can express its undisputed appeal.