Why do we like "destroyed" fashion? When wear and tear is the texture of our individuality

The first reaction to Balenciaga's Paris Sneakers was outrage, followed closely by a social blizzard of accusations and controversy. Then, the Georgian designer thought well of deteriorating Stan Smiths on his latest runway show with adidas, arousing the curiosity of the most astute eyes. In 2020, it was the turn of Gucci, which with a pair of ripped 140€ tights - instantly sold out - stirred up a media fuss of outraged ravenous for explanations, while Alessandro Michele watched his socks, created in the name of fashion's transience, scatter among the most famous celebrities. But the first to lay the groundwork for this controversial fashion trend was John Galliano, whose Dior SS2000 inspired by the clochards of the Parisian suburbs earned him a parody in the film Zoolander, as well as a myriad of protests from homeless communities around the world. But the success of "destroyed" fashion goes far beyond the resentment and disappointment of the general public. Underlying the principles of luxury is the inaccessibility of the product: the more unattainable it is, the more we desire it, the more we take action to obtain it.

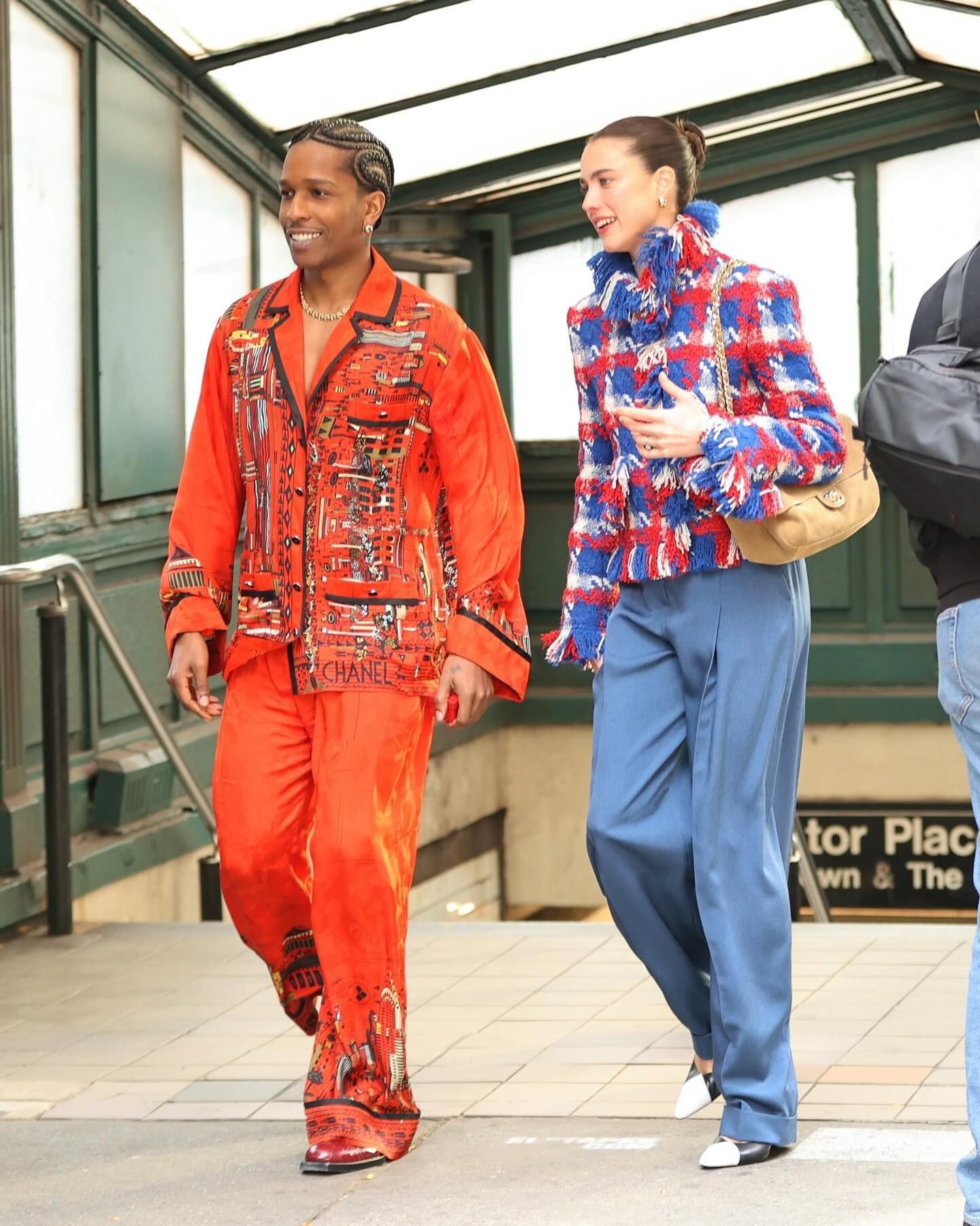

According to the "trickle down" theory, formulated by Georg Simmel in the late 19th century, the high fashion of the upper classes "trickles down" to the lower classes, who try to imitate it. With the emergence of ready-to-wear, the mechanism has been reversed, styles are no longer generated in high society, but from the lower social classes: high fashion has only to reinterpret, in an aesthetic key, the voice of the people. Demna has done nothing more than stick to the "bubble up" theory, as the biggest fashion brands have been wont to do for more than sixty years, but in his shrewd marketing move he has leveraged a psychological component that is rarely, these days, solicited. The Paris Sneakers, as well as Yohji Yamamoto's shredded mohair or Maison Margiela's frayed socks, are not just a guilty pleasure of "rich people who want to dress poor," as the social crowd has railed. It would be too limiting to think that more than 150 years of fashion history today is summed up in a mocking media strategy, and it would be equally reductive to label Balenciaga's latest product as yet another mere provocation.

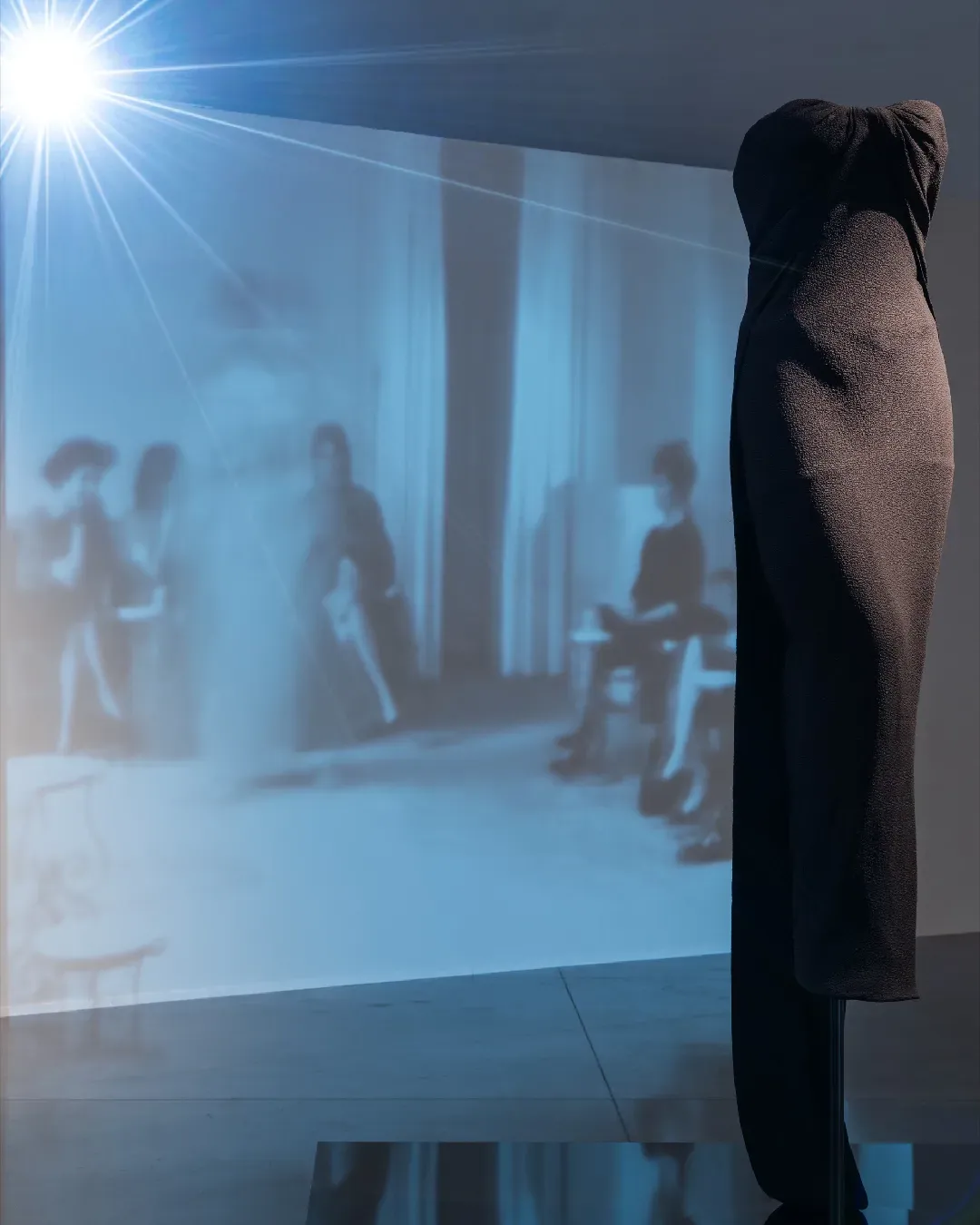

If destroyed and imperfect fashion is replacing glossy luxury, the reason is at the origins of our individuality. How many of us, during our adolescence, were really carefree? Just asking this question is enough to advance a step toward understanding this latest, paradoxical turn of ugly fashion. Not everyone feels free to express who they really are, but almost everyone wants to show that they are authentic and irreplaceable, flaunting a series of flaws that act as a guarantor for their uniqueness. The allure of destroyed fashion makes its way into our desires like a fetish and connects with our rebellious and nonconformist urges. But even before fashion, the Art Brut ("raw art") of 1945 collected artworks by marginalized artists, confined to psychiatric hospitals and prisons, completely impervious to the aesthetic and collective norms of the time.

Spontaneous and self-taught creations, born solely from the impulse of artists "in spite of themselves," stood on a par with canonically recognized works of art, while ignoring the norms of traditional artistic beauty. Their strength, which over the years has influenced a multitude of artistic currents from Pop Art to graffiti art, lies in their ability to transform something ugly into an unattainable work of art through a primitive cry of suffering and rebellion. In the same way, deteriorated, torn, and worn fashion gives voice to a transgressive side of our personality that we communicate through style: through a "destroyed" dress we share with the world all those imperfections that we are used to hide, but that make our story unique and interesting. Paraphrasing Balenciaga's latest slogan, a deteriorated dress lasts forever, and we like it precisely because it has something to tell.