Has mainstream fashion really killed the dandy? From Brummell to Harry Styles, a reading of dandyism from a contemporary perspective

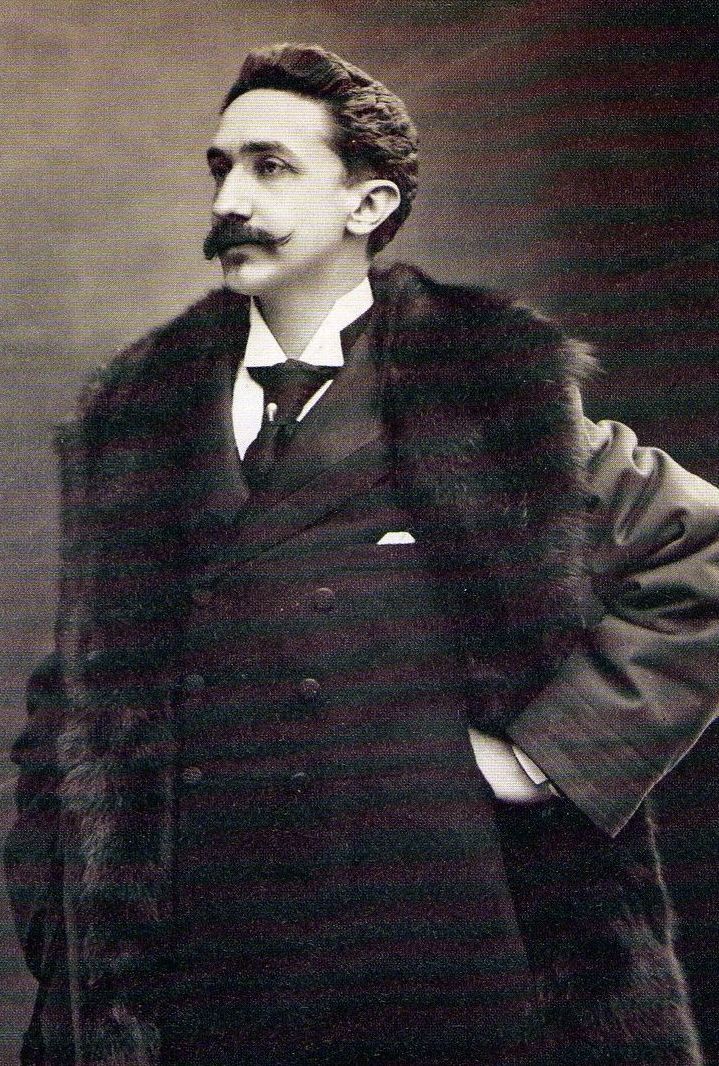

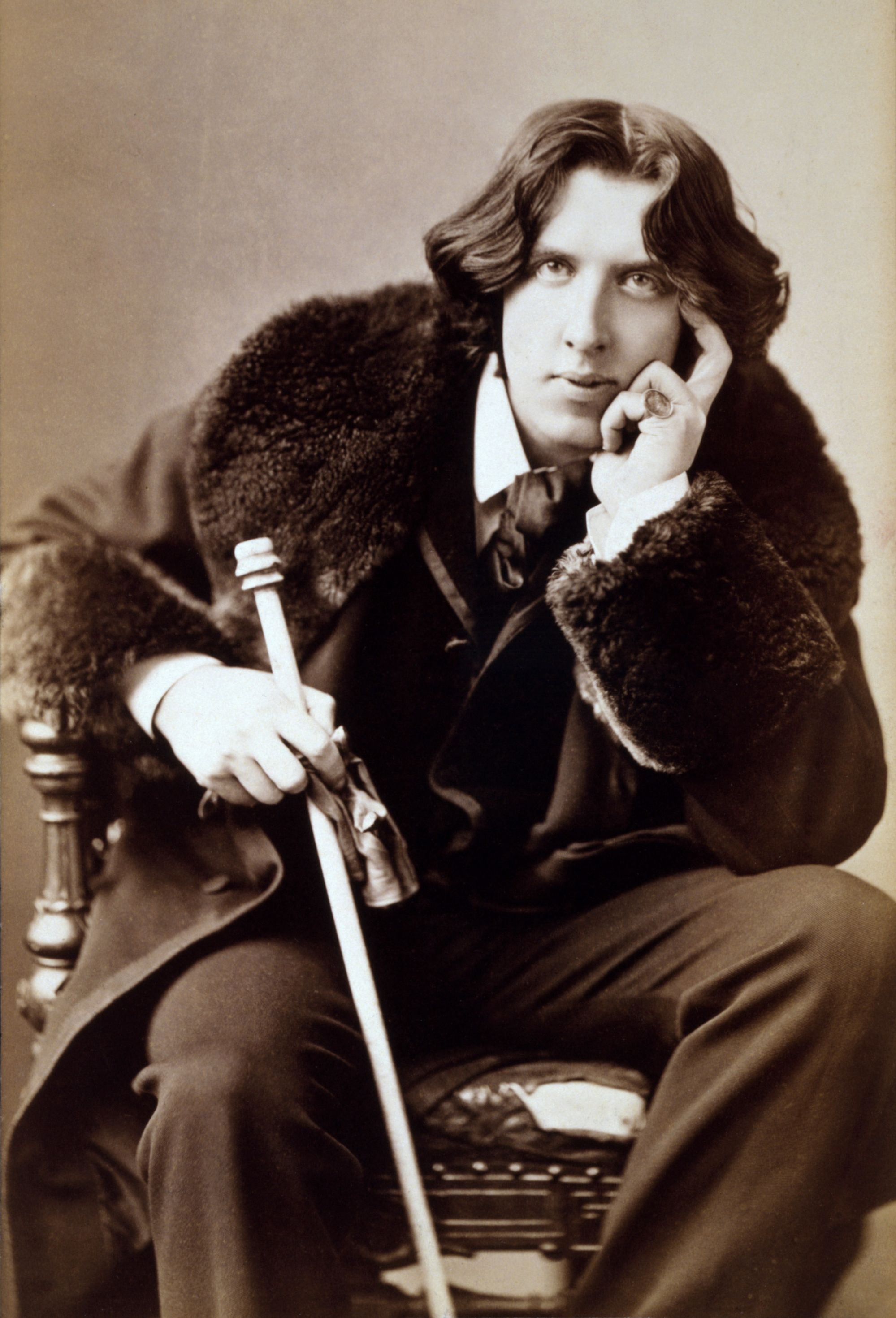

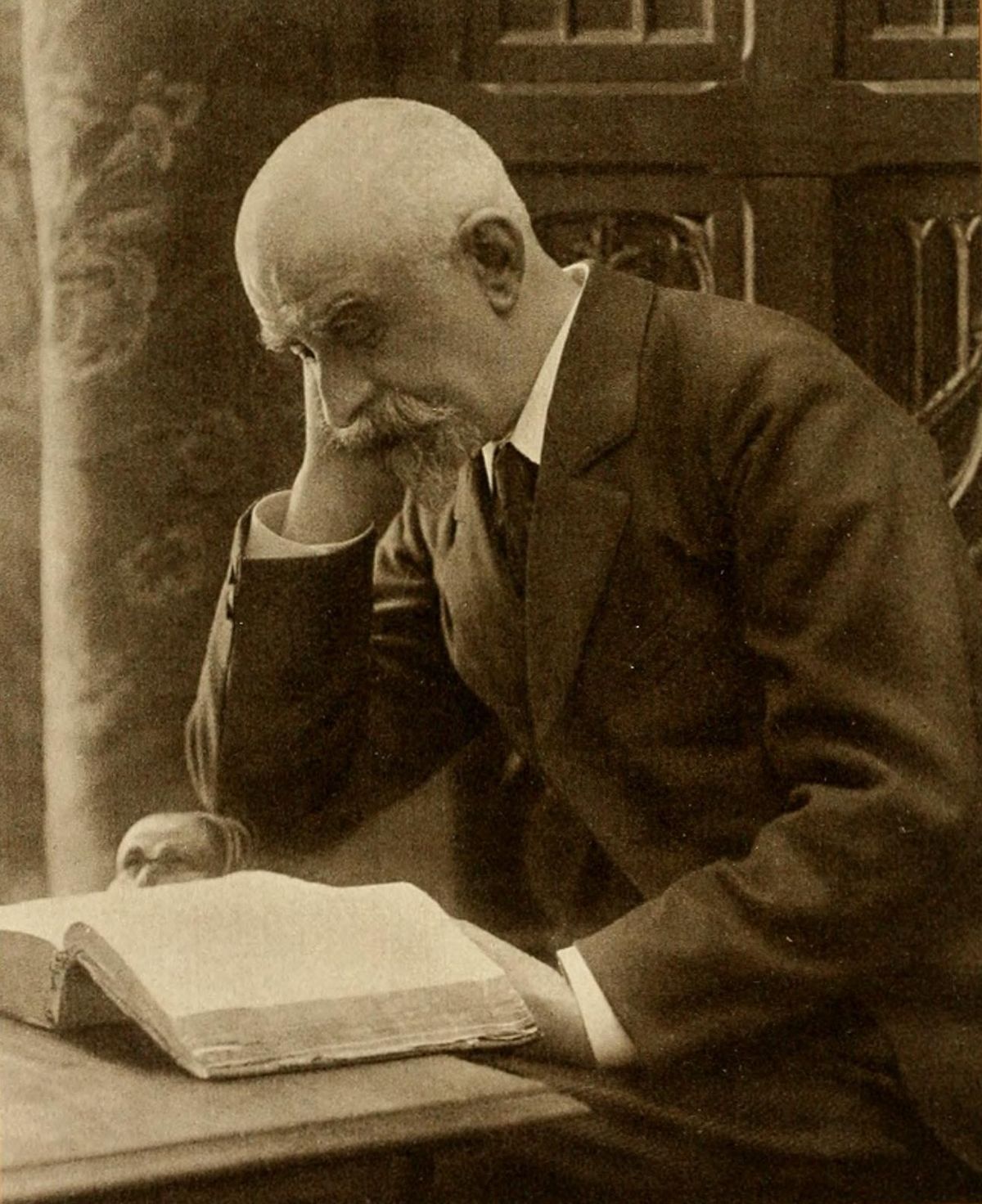

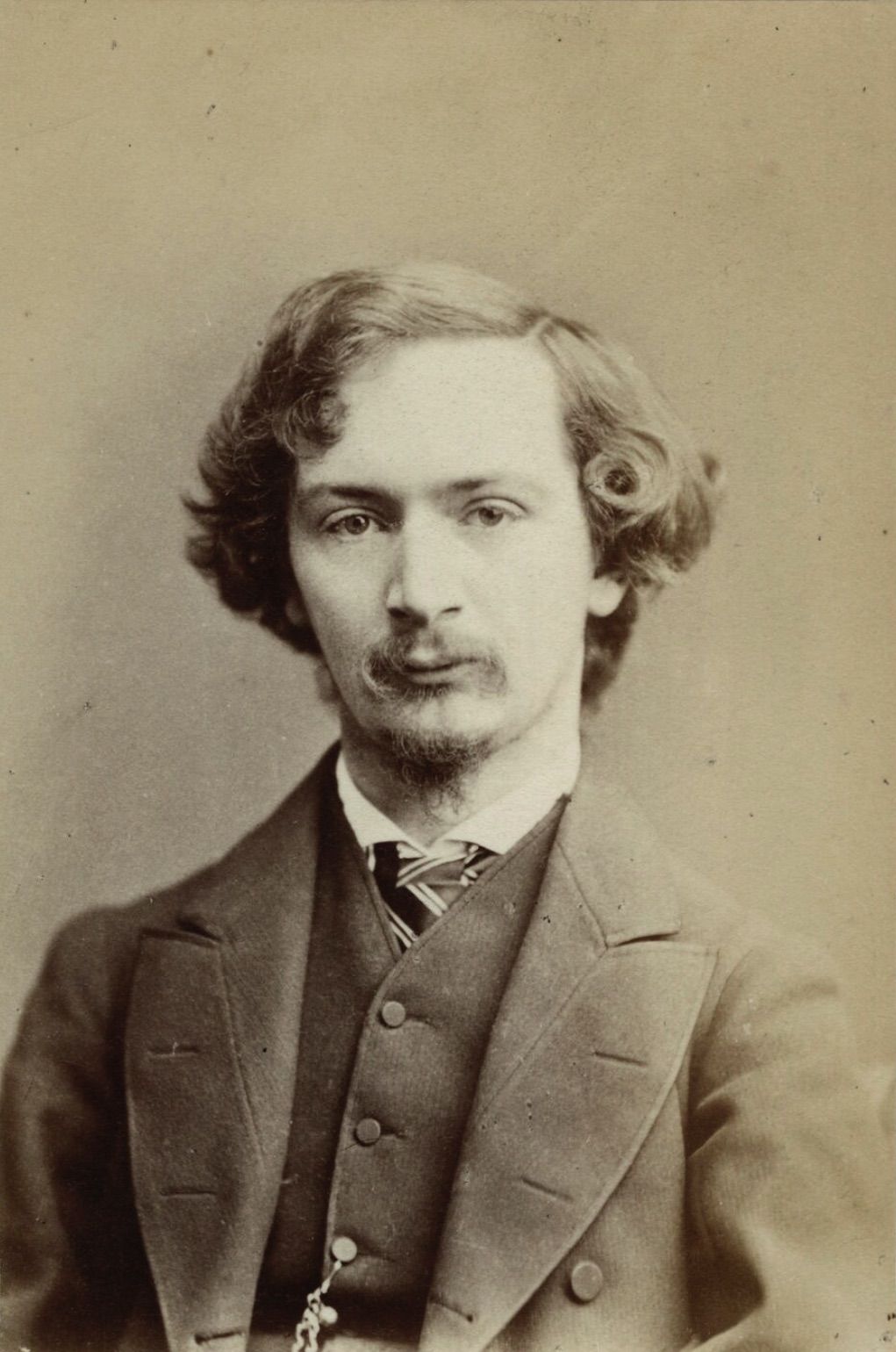

We are in the 60s when Roland Barthes, French critic, semiologist and intellectual guilty of having spent liters of ink in the attempt to define the cornerstones of a fashion theory, writes that the phenomenon of dandyism is essentially dead. Brutally killed by fashion itself, the dandy is but the memory of an aesthetic, a lifestyle and a technique that had its acme during the 19th century, hermetically sealed on the faces of Lord Brummell or Oscar Wilde. Aesthetes to the point of becoming deliberately self-referential, these well-dressed characters radicalized the dress of the distinguished man by exhibiting a cult of image that went from wetting their gloves to make their hands fit better to fixing their ties for hours. Those were years in which, in fact, there was no highly specialized fashion system in its creative and managerial departments as there is today. They were times when social inequality was something absolutely natural, made significant, moreover, by a grammar of dress that did not get lost in subtle interpretative games.

The French Revolution had in fact changed male dress in its form and substance - the utopia of a uniform-like tailoring without any particular discriminating features was spreading - leaving open the valve that would give the individual the right and the possibility to differentiate himself from others. This differentiation could no longer be achieved by playing with the uniform itself, but rather by intervening on the distribution of its components: a buckle, a button, a tie knot became strategic clasps to save identity. This was the beginning of a season of empowerment of the detail (the cane, the buttonhole flower, the pocket watch), the aesthetic category that would become a poetic manifesto and the lifeblood of the dandy's creative project. Between stylistic quirks and a know-how unknown to the masses from which he obsessively avoids, he manipulates the dress to the point of denying it any common value.

@pinsent_tailoring My BBC feature, just trying out TikTok #boredvibes #dandy #mood original sound - pinsent_tailoring

The birth of ready-to-wear, the industrialization of clothing and the development of fashion publishing have led to its death in the words of Roland Barthes. Not even luxury, promulgator of an exclusivity still able to enchant followers and not, can leave room for the dandy precisely because it acts as an incubator of standards, norms and "laws" that contradict the first rule of dandyism: the creative uniqueness. In fact, the ethics and lifestyle of this figure were based on an exquisitely inventive freedom aimed at absolute distinction from the masses, which could draw on the wardrobe of the wealthier classes or, on the contrary, simulate a scruffiness in order to distance themselves from it. Reduced then to freedom of purchase by the mechanisms of collective imitation spread first by boutiques and then by ready to wear, the phenomenon of dandyism was emptied of its ambitious project of singularity pushed to extremes. How legitimate would it be then to try to outline its contours in the contemporary world? After all, we are living in years in which the problem of creativity is faced according to perspectives and reflections that have called into question the concepts of authenticity and invention, following alternative paths explored by new research paradigms.

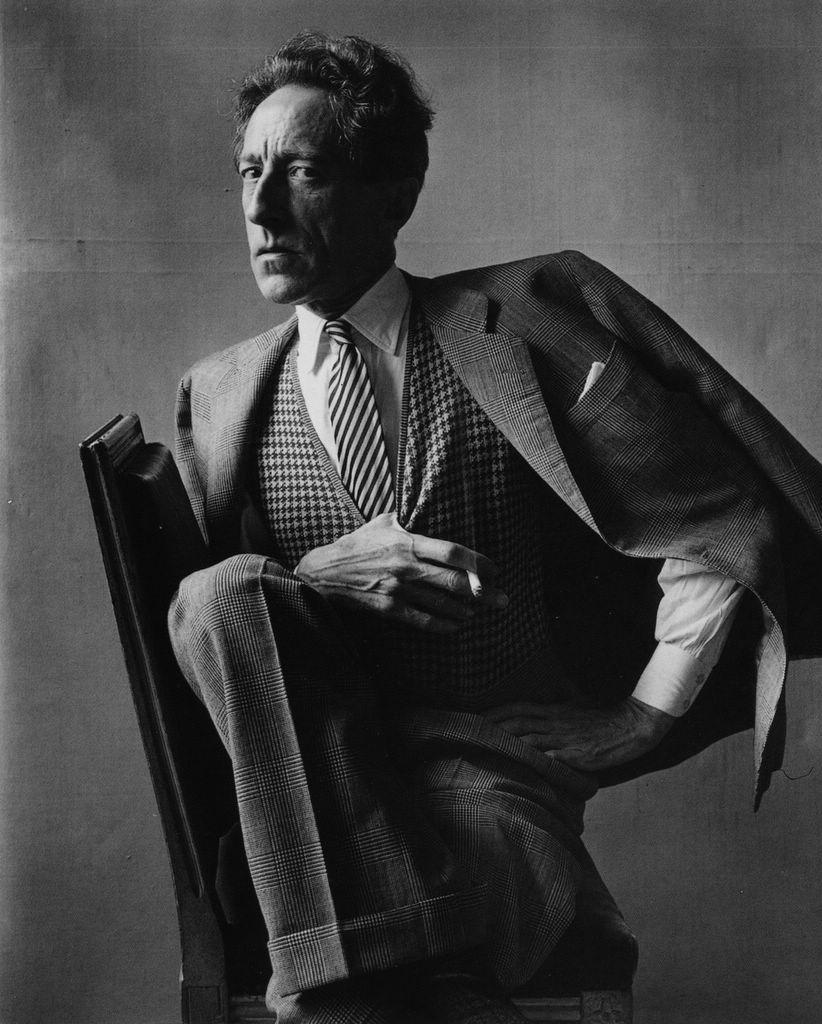

Excluding, therefore, the path of absolutism that we have seen to be the workhorse of the first dandy, it is possible to trace at least some narratives capable of replicating forms of dandyism. This is the case of celebrities who, albeit assisted by figures such as fashion stylists or editors, come to stage a performance of the dandy. Body, clothes and styling come together in a re-signification of the entire creative process of the dandy that, while not respecting the cardinal principles, contribute to the exhibition of a final product shaped on the same imagery. When in 2020 Harry Styles shows up at the Brit Awards in a yellow Marc Jacobs suit - the three-piece suit belongs to the spring-summer 2020 womenswear collection -, it is legitimate to read between the lines a direct reference to the microcosm of dandyism. The British singer is in fact used to propose Gucci looks that, from styling directed now on camp and now on glamour, end up recovering traits of dandyism.

Recovery that is at the center of practices related to vintage, obsession in vogue among members of the Z generation, the protagonist of a social campaign that has gone viral on Tik Tok in which they show their purchases through video hauls. We refer, specifically, to a generation able to consume entire decades of trends in a few months, if not weeks. Yet the interest in vintage remains vital and could even be used as a reservoir from which to draw strategically key elements of dandyism. This can be seen in the looks of boys or girls - the phenomenon of dandyism is not the preserve of the male sex - who use details of vintage clothing or accessories such as hats, cufflinks, handkerchiefs or lace-up shoes to reproduce a "dandy" mood. It is clear, perhaps superfluous, to reiterate that it would be almost entirely improper to advance the hypothesis of a pure form of dandyism, if not as a practice to embed and reinterpret in a crossover perspective to assert an identity with precise references.

The same discourse can be extended to brands whose DNA is compatible with an aesthetic willing to come to terms with the stylistic acrobatics of this figure. This is what Yohji Yamamoto did for the FW22 collection, flirting with 19th century literature and clothes in a game where the manias of the dandy - including the scapigliate hair - become the corollaries of a manifesto of resistance to time that intercepts the categories of romanticism, punk and surrealism. A project only partly shared by Kim Jones at Dior Homme who, in the FW22 collection, tries to imagine a soft dandy inspired by the codes of the historic French maison. The reinterpretation of the Bar jacket, the recurrence of the floral motif and a decorative approach that can also be seen in the jeweled gloves outline a language that winks in a more or less explicit way to the clothing rituals of the dandy, made more fluid and less loud by an interpretation modeled on modern genderless variants. A question that also closely touches the work of Silvia Venturini at Fendi, creator of a male wardrobe (re)thought for occasions in which classic does not rhyme with nostalgic: the entire FW22 collection aspires to an idea of distinct elegance that, from sensual cut-out cuts combined with Mary Jane's with straps and chockers of pearls culminates in outfits declined according to the finest sartorial intelligence of the dandy.

A scenario further shared by a large group of gentlemen who, at events such as Pitti Uomo, display tailored suits so studied as to establish a movement of marked resistance to ready-to-wear to seal the poetic dress code of a subculture still linked to the mania for detail in every detail. Not a fashion victim, nor even less a fashion icon, the dandy was and is rather a fashion curator who steals the very idea of style. And, in doing so, he clashes with the very world that has limited and regulated his aesthetic imagination: fashion has not killed him, it has anesthetized him in order to lower him into a dimension that is no longer individualistic and narcissistic, but of common collective reflection.