Is personal style still a thing? Influencers' feeds and luxury brands' policies reflect a homologated and repetitive fashion scene

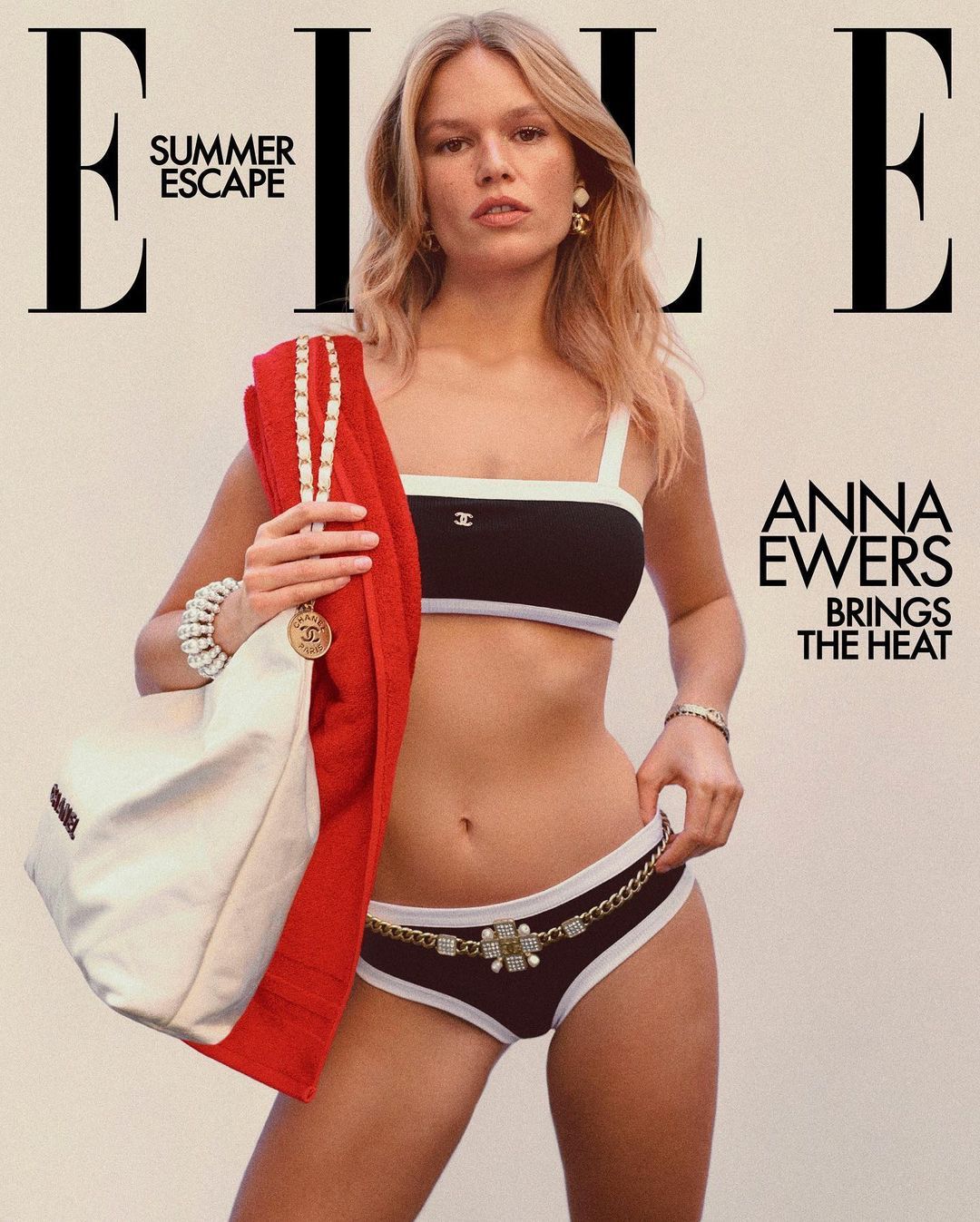

"The Miu Miu skirt is so short that it seems to have no end. For the last two weeks, it has made nearly daily appearances: on the covers of magazines, on the bodies of celebrities and influencers, and as the subject of articles about its reach". It was the beginning of March when, in the New York Times, fashion journalist Jessica Testa recounted her close encounter with what is undoubtedly this season's look, on the occasion of Miu Miu's latest Parisian fashion show. In addition to having sparked heated controversy about its actual wearability, the constant reappearance of that micro mini-skirt and matching crop top, worn by dozens of celebrities and influencers with minimal differences in styling, has given shape to a host of personalities all dressed the same, a symptom of an aesthetic flattening that makes you wonder if personal style still exists.

It's a well-known fact that luxury brands are used to lend pieces of clothing to the guests attending their fashion shows, an infallible method to give prominence and visibility to selected looks, to be enhanced, to be highlighted as the season's must-haves. Brands and designers aim at having direct control over their own image and storytelling, a goal that has become more and more challenging with social media, where they are more vulnerable to criticism and controversy. Establishing predefined looks, choosing their styling and who will wear them allows them to overcome this problem, at least in part.

Although Testa recounts the different ways the various invitees to the Miu Miu show chose to wear *that* look, by taking a look at the street-style photos one realizes that there was little variety. As @grrlbossbab pointed out on TikTok, "we've reached such a level of consumerism, where designer clothes, which are meant to be investment pieces, are like the epitome of micro trends. And I can guarantee you that none of these influencers will be wearing this look in a year". By choosing to show only one way to wear a certain item, brands limit its appeal, affecting the predisposition of a public interested in making an important purchase due to its versatility, the possibility of wearing it in many different ways, in short, with the guarantee of having made a long-term investment that will pay off. So instead, even luxury becomes fast fashion.

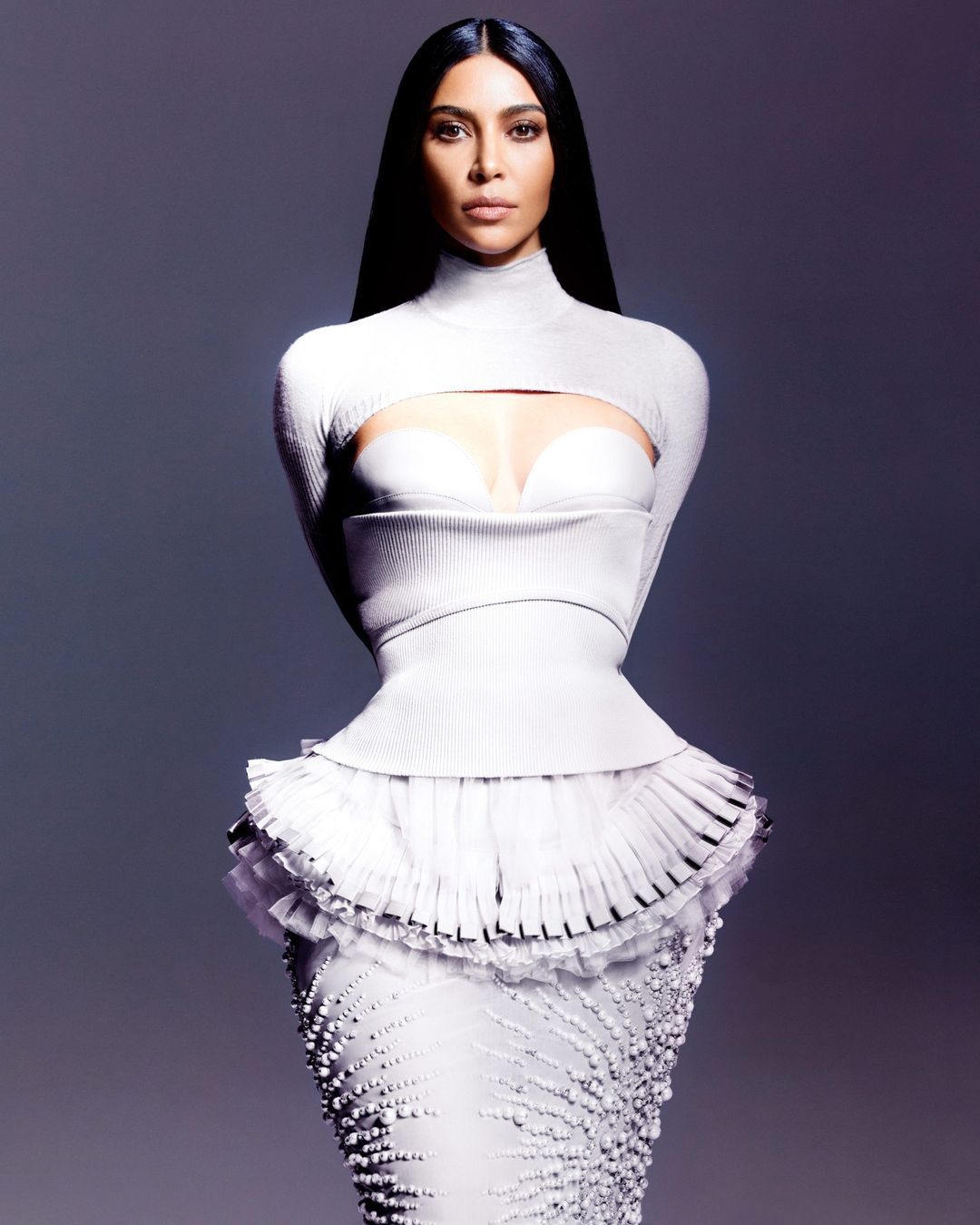

Looking at the matter from another point of view, that of the influencers, one wonders if the digital creators, dressed from head to toe in a single brand to attend their show, still have a personal style. If their feed is a series of gifts, seeding, of it bags to advertise, where is their taste, their filter? Their role as intermediaries, as curators, between the fashion houses and their followers no longer exists. If every influencer receives the same product and shows it in the same way, their posts become yet another advertising campaign to be skipped while scrolling on Instagram.

The ubiquity of Miu Miu's SS22 set, a perhaps overused example at this point, but one that has already had illustrious precedents - see under Gucci SS11, or Prada's FW18 banana-print garments - is also indicative of another typical practice for fashion houses: the full look policy. As recounted in a BoF article from 2017, many luxury brands require magazines and fashion publications to use full looks, often replicating exactly the outfit that walked on the runway (a practice that over time has increasingly affected the red carpet too). This is a very frequent policy, especially when a new creative director comes along, in order to make a clean cut with the past and convey the new image of the brand in a clear and unequivocal way. Nicolas Ghesquière was one of the first to introduce this policy first at Balenciaga and then at Louis Vuitton, followed by Riccardo Tisci at Burberry, but the policy is also valid at Christian Dior and Celine.

It seems, however, that the most demanding was Raf Simons, at the time at the helm of Calvin Klein. "The rule is that any items from Simons' debut ready-to-wear collection (Autumn/Winter 2017) must be photographed as a full catwalk look, not styled with any other brands (even non-branded apparel and vintage clothing) or even items from other looks from the same catwalk collection. Even accessories must not be worn with any other piece of clothing: the brand will provide a nude nylon bodysuit to accompany a pair of boots. Essentially, the clothes shouldn't be styled at all, but merely placed on the model as seen on the runway and in the brand's advertising campaigns."

And since many of these major fashion houses are also major advertisers for fashion magazines, it's clear that these diktats will be embraced and executed. "This shoe is the reason we're on this shoot. It's paying for the shoot", stylist Melanie Ward told BoF about it. Here, the stylists. At this rate, where will their work go? Will their job be limited to having personal relationships with brands, so they can be sent the most desired looks of the season, but without having any say in the creative process? "You're not a good stylist if you do full looks — you're a dresser", Alexandra Carl, fashion director at Rika, told BoF.

The fashion industry is first and foremost an economic machine, and only in a second moment can it be a creative system, at least for the conditions that exist today, in particular the co-dependent relations between magazines, brands, stylists, and creators. However, it's undeniable that seeing the same looks over and over again, unchanged and unchanging, from the catwalk to the magazines to the celebrities and influencers for the next six months, causes a flattening, boredom, a homologation that is antithetical to the very nature of fashion, and of fashion magazines. It's paradoxical that in a historical moment where we're all hyper-connected, partially more open, free, interesting, and democratic, which has allowed the fashion system to establish a direct relationship with a wider and more varied public, designers and brands are so frightened by this media exposure that they want to establish absolute control over their image, by any means possible. Possibly losing many exciting and unexpected possibilities on the way.