What ever happened to grunge? Investigation of a trend above suspicion

These days, following the success of Matt Reeves' The Batman at the box office around the world, Spotify has recorded a huge 1200% increase in streams of Nirvana's Something in the Way, a song that is part of the film's soundtrack. The phenomenon is quite natural really, but it still highlights the deep fascination that the pop culture world and its audience feel towards 90s grunge. Three weeks ago, by the way, the grunge genre made headlines when two days apart the 55th anniversary of Kurt Cobain's birth was celebrated and news of the death of Mark Lanegan, legendary pioneer of the genre, was released. Also during the past weeks, in the course of fashion month, the fashion press has used (and abused) the word grunge to refer to the shows of AC9, Philosophy di Lorenzo Serafini, Coach and even Louis Vuitton and Miu Miu. Even Chiara Ferragni was given the epithet "grunge" for the simple fact that she showed up at the Balenciaga show with a thick layer of eyeliner and an oversized trench coat. And just as the press started using the term as a generic portmanteau (according to SkyTG24, for example, python boots and a khaki leather dress would be grunge), new generations on TikTok (where the hashtag "grunge" has 4.1 billion views) have started to identify as "grunge" the style of any subculture, from the punks and goth malls of the '80s to the emo of the early 2000s, including the style of the infamous metalheads and hipsters. But if everything is grunge, then nothing is grunge.

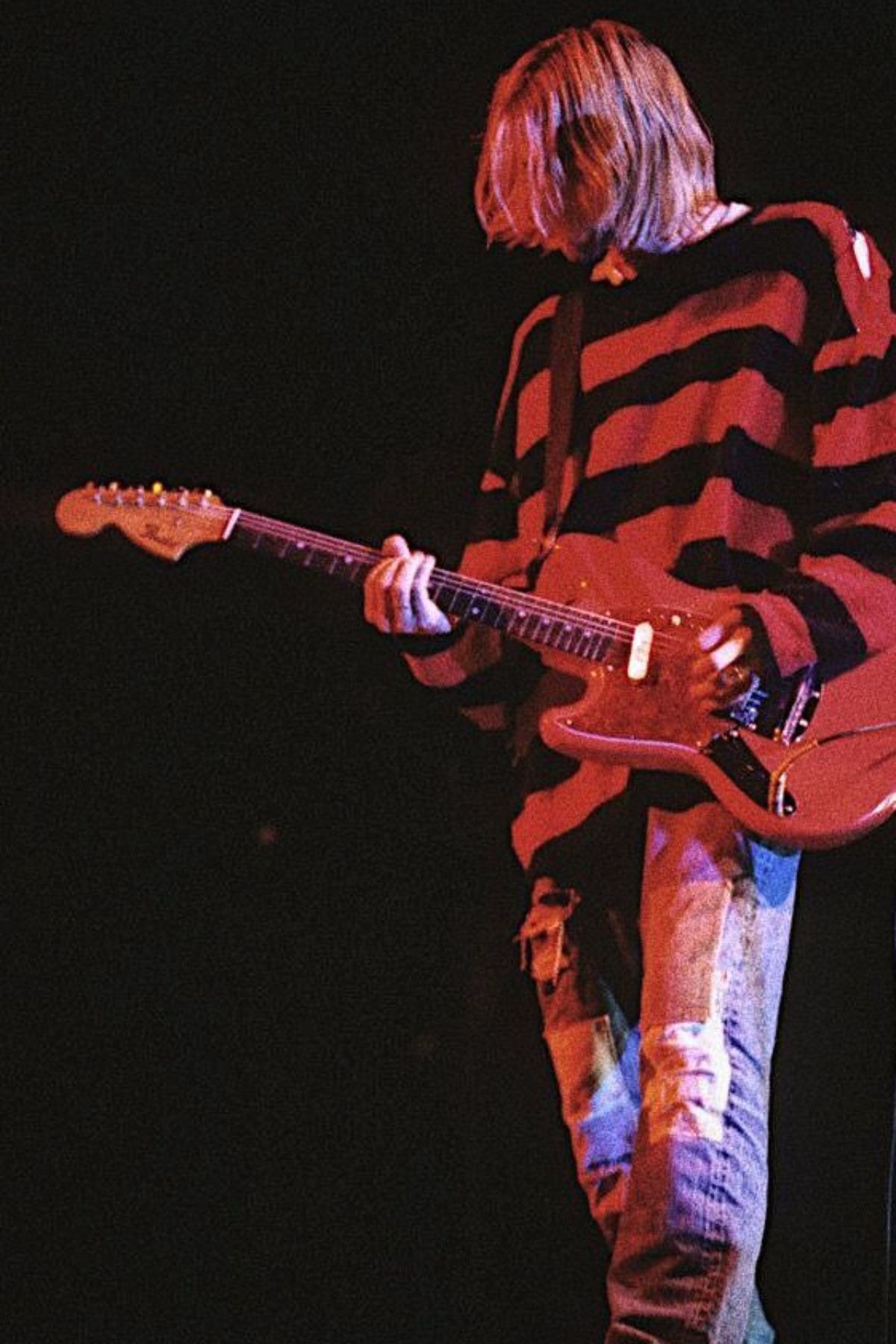

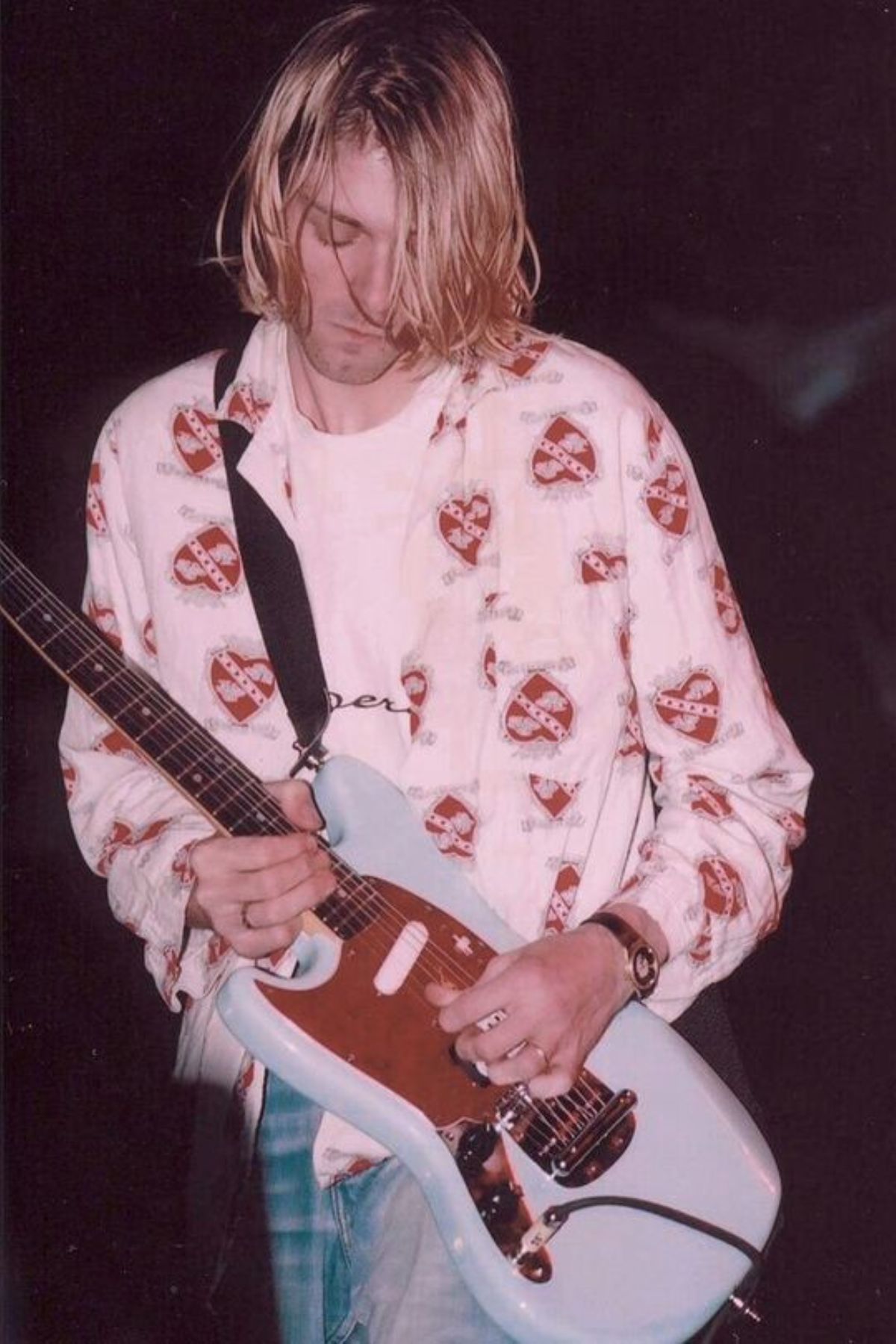

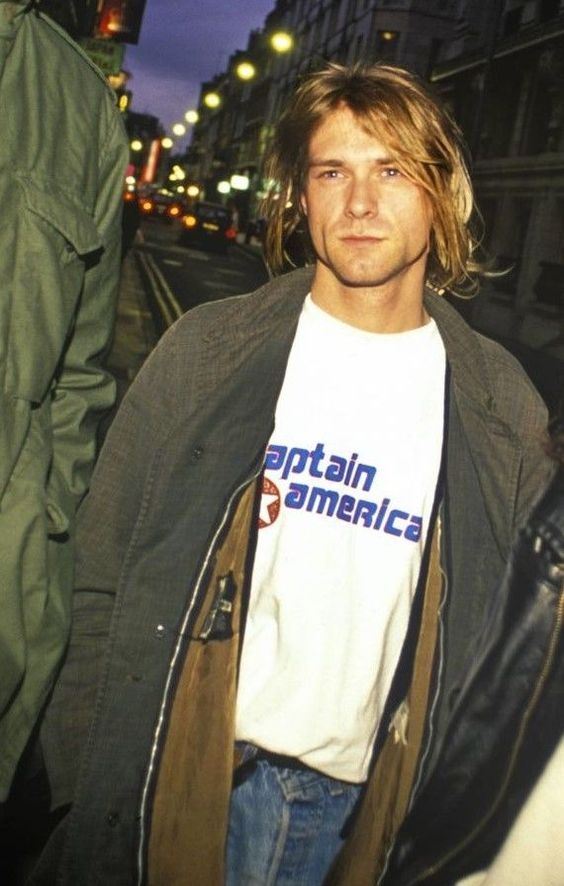

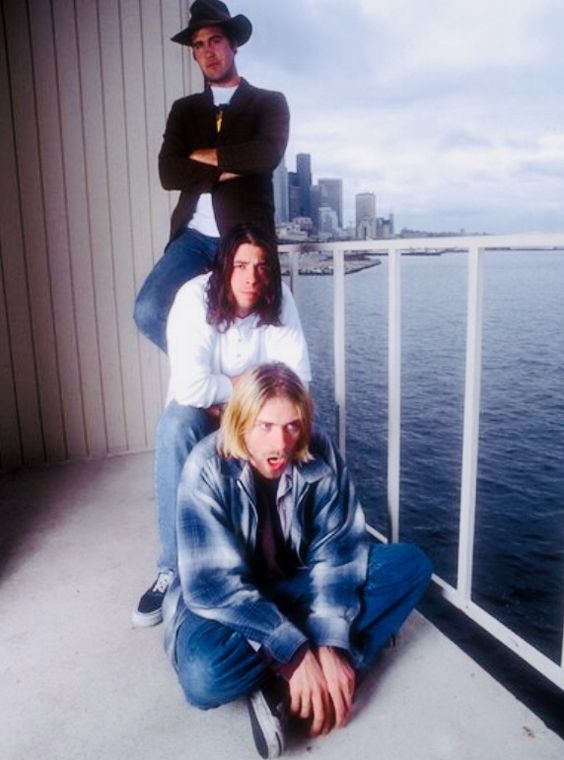

This desemantization of the concept of grunge is the direct result of the commodification of a genre that, originally, was born as a disillusioned, apathetic and sometimes angry rejection of social conventions at the turn of the '80s and '90s. This rejection also passed through the discomfort felt in the face of popularity: after the huge success of Smells Like Teen Spirit on MTV in 1994, Cobain himself explained to Rolling Stone how the song was a source of embarrassment for him, almost as if the main exponent of a much broader cultural movement had discovered flattened and commercialized in a hit that even those who had nothing to do with grunge loved and hummed everywhere. The popularity of Smells Like Teen Spirit (which, by the way, Nirvana themselves stopped singing at their concerts at one point) was just the beginning of a slow cultural transition: first, Nirvana became the only grunge band in existence in the mainstream consciousness that gradually erased Pearl Jam, Mudhoney, Alice in Chains and so on; and later, the absurd popularity of their merch led to their name and logo becoming one of the most popular graphics in the mass fast fashion market and beyond - but also leading to a song like Smells Like Teen Spirit becoming the first '90s music video to surpass one billion views on YouTube.

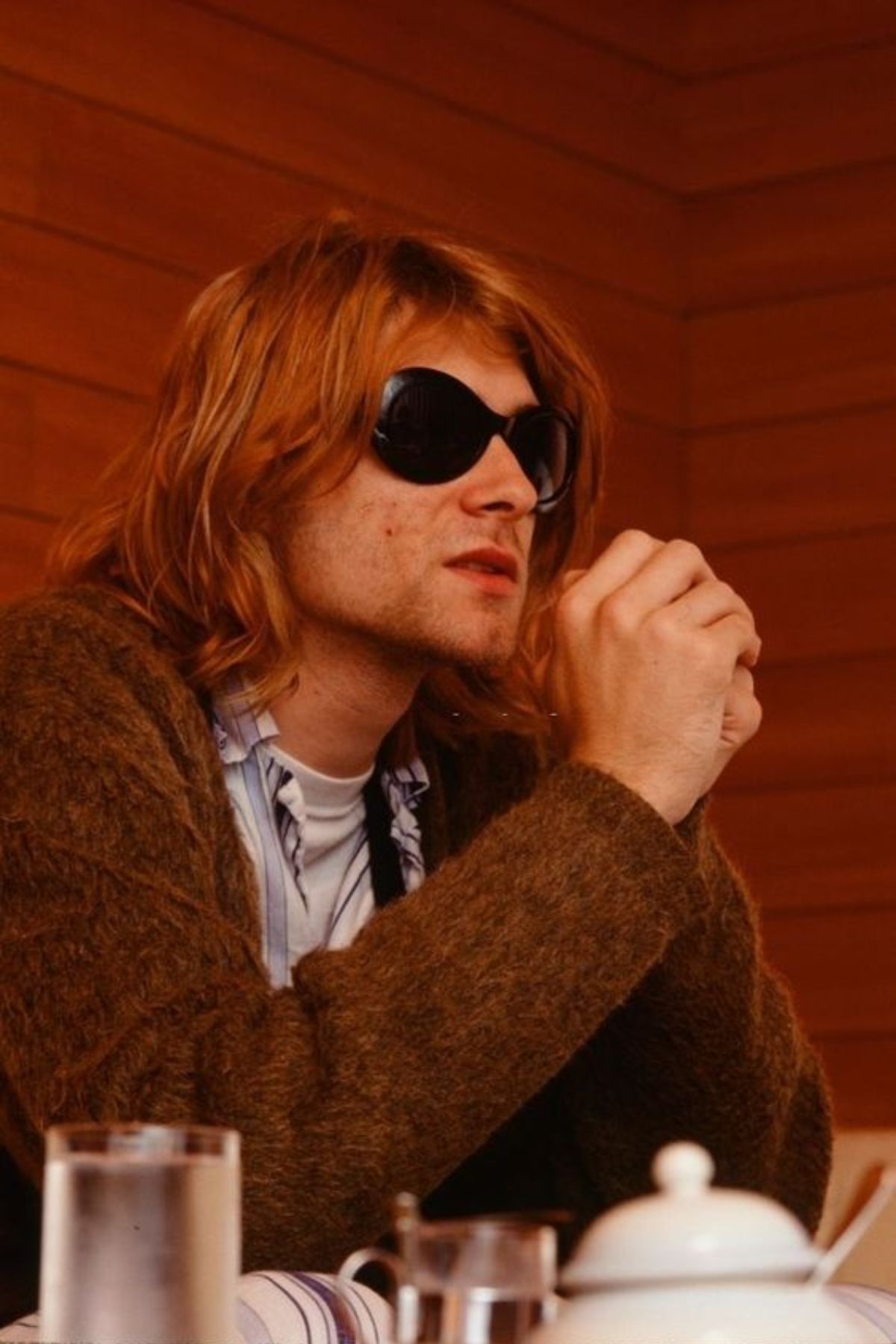

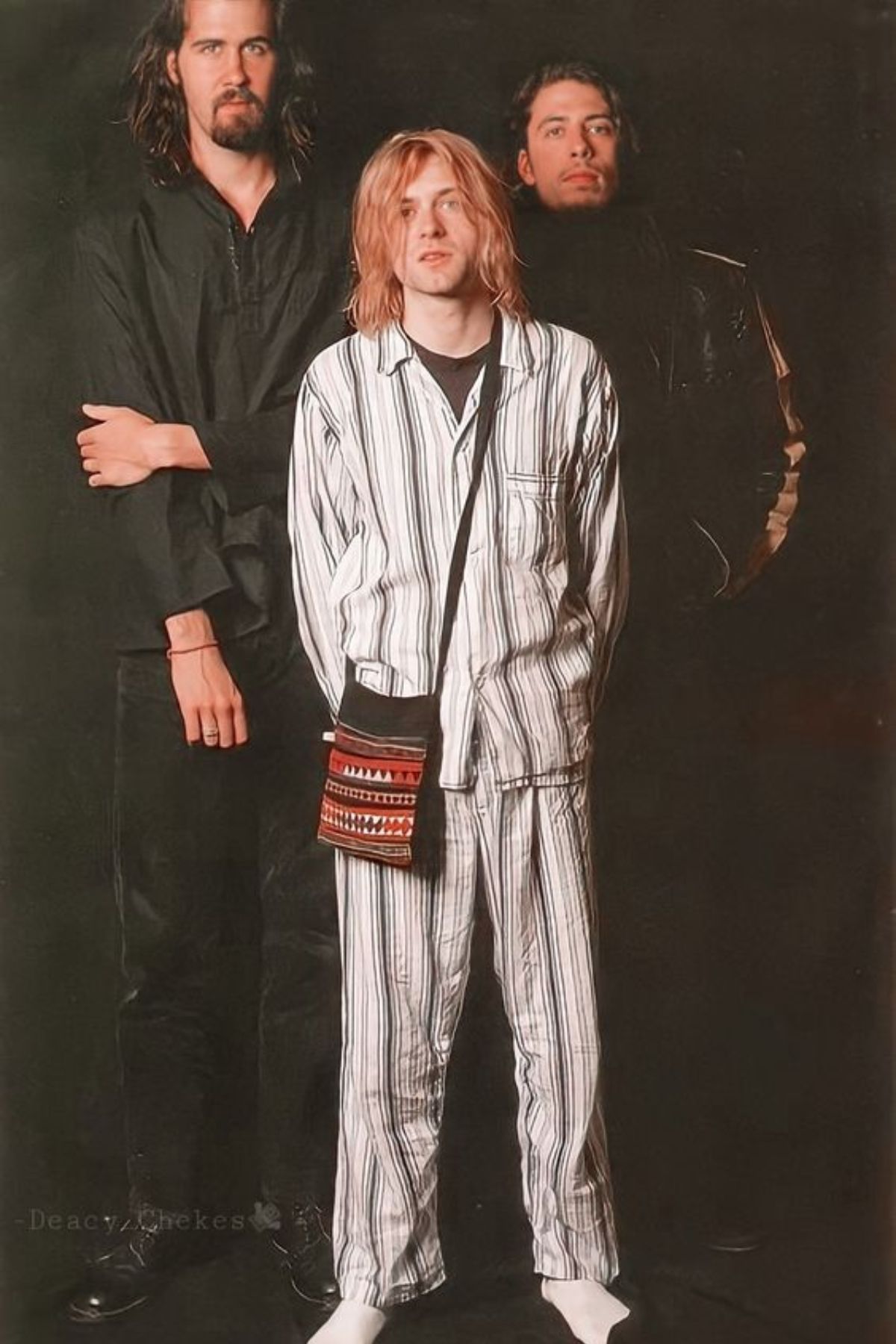

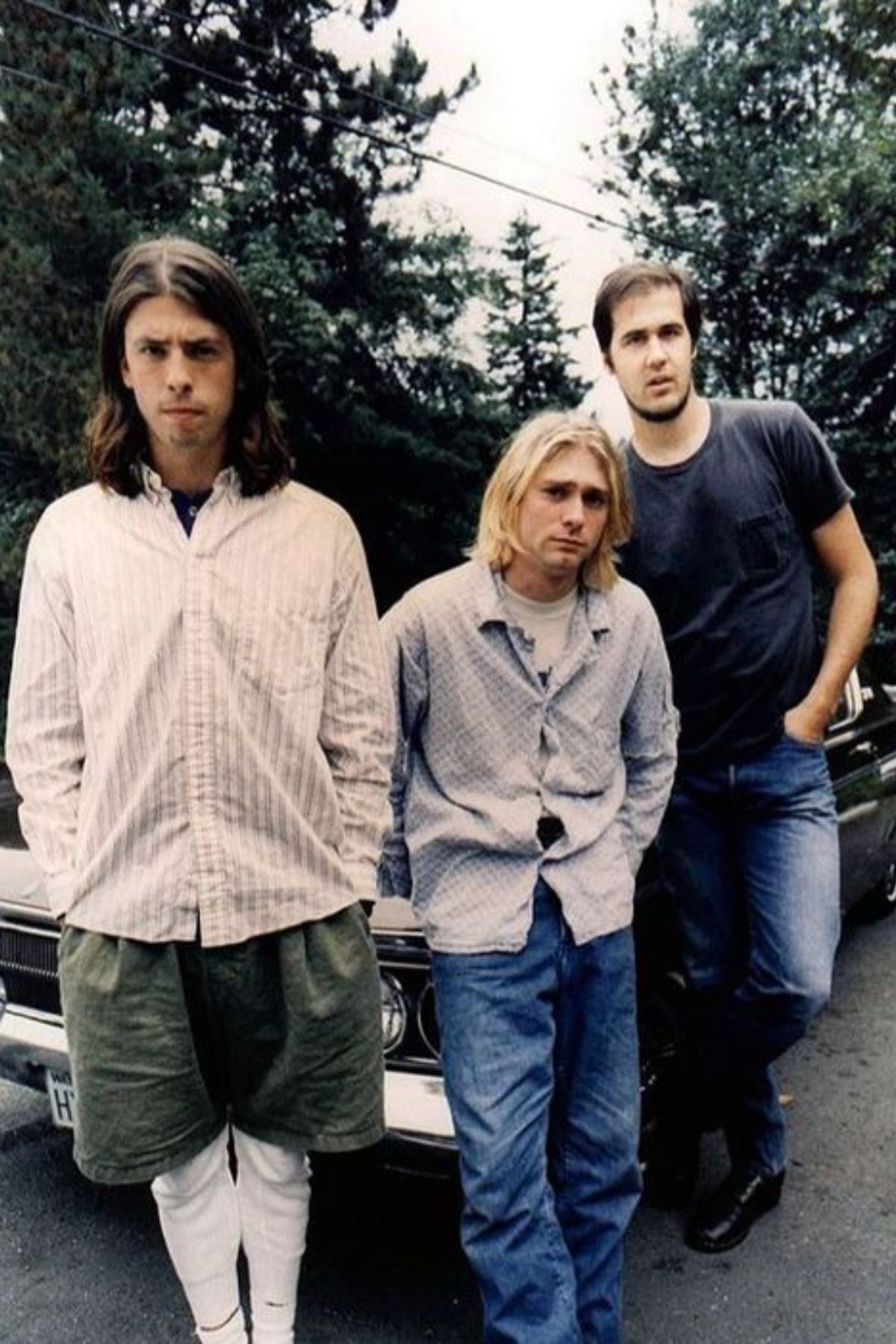

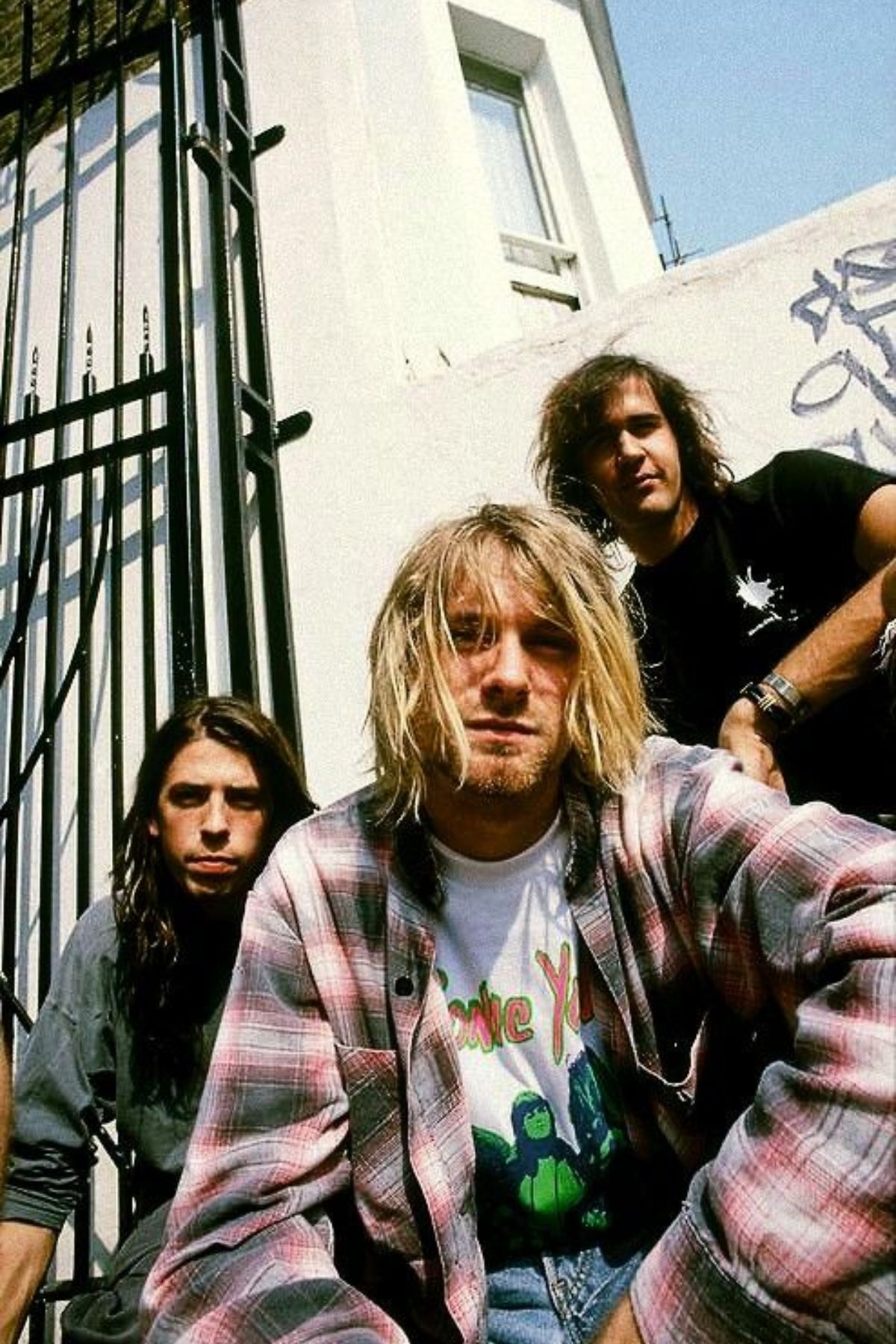

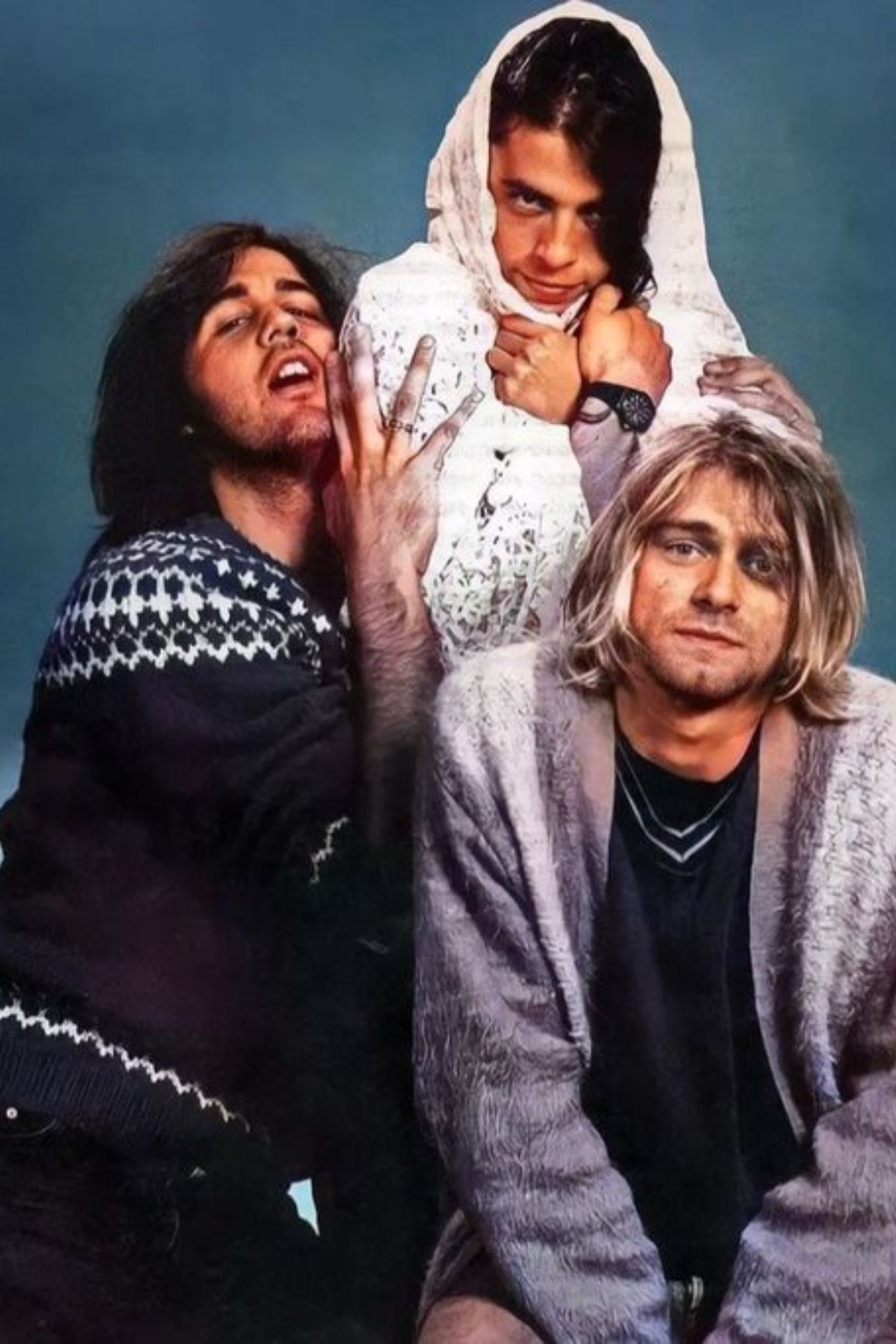

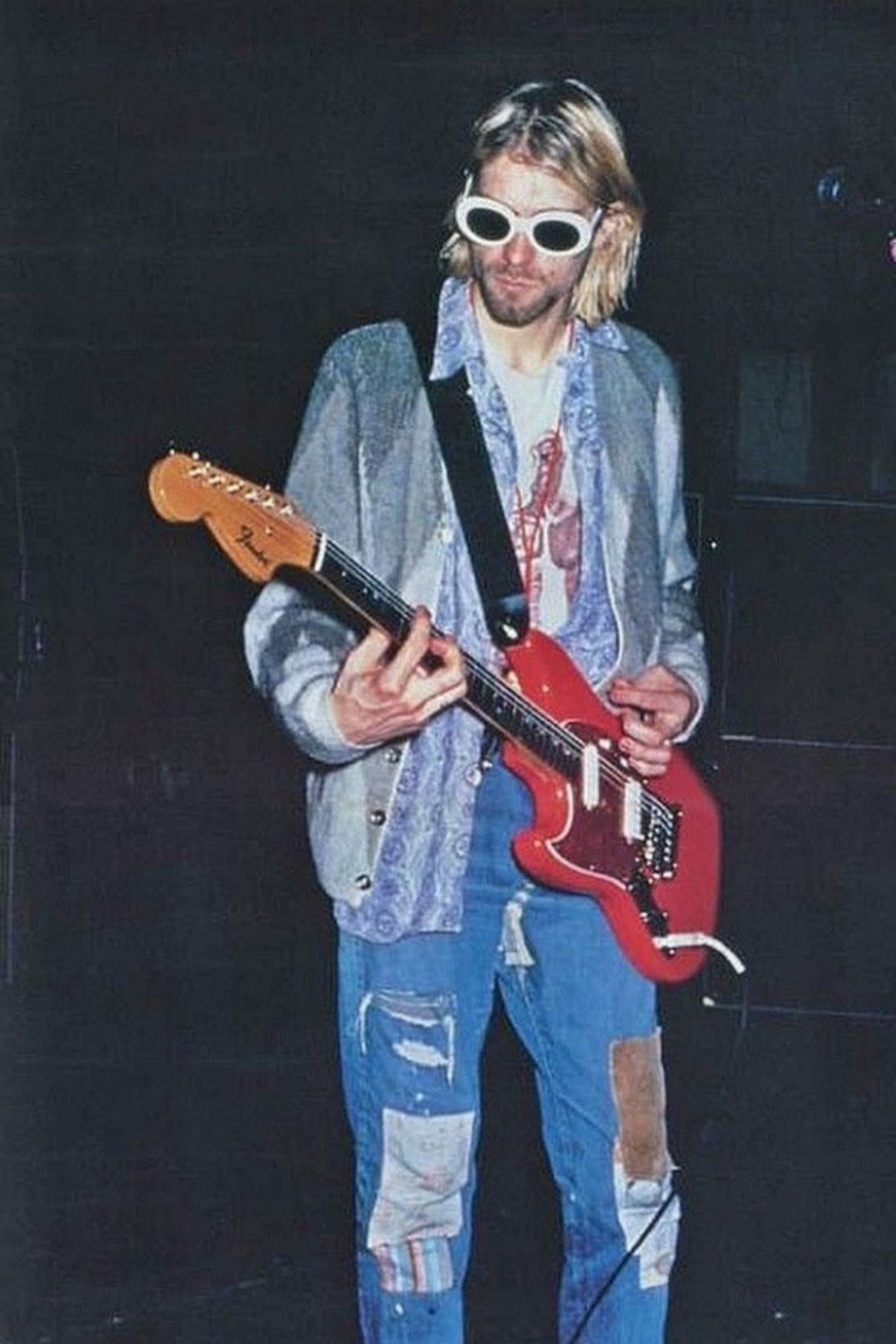

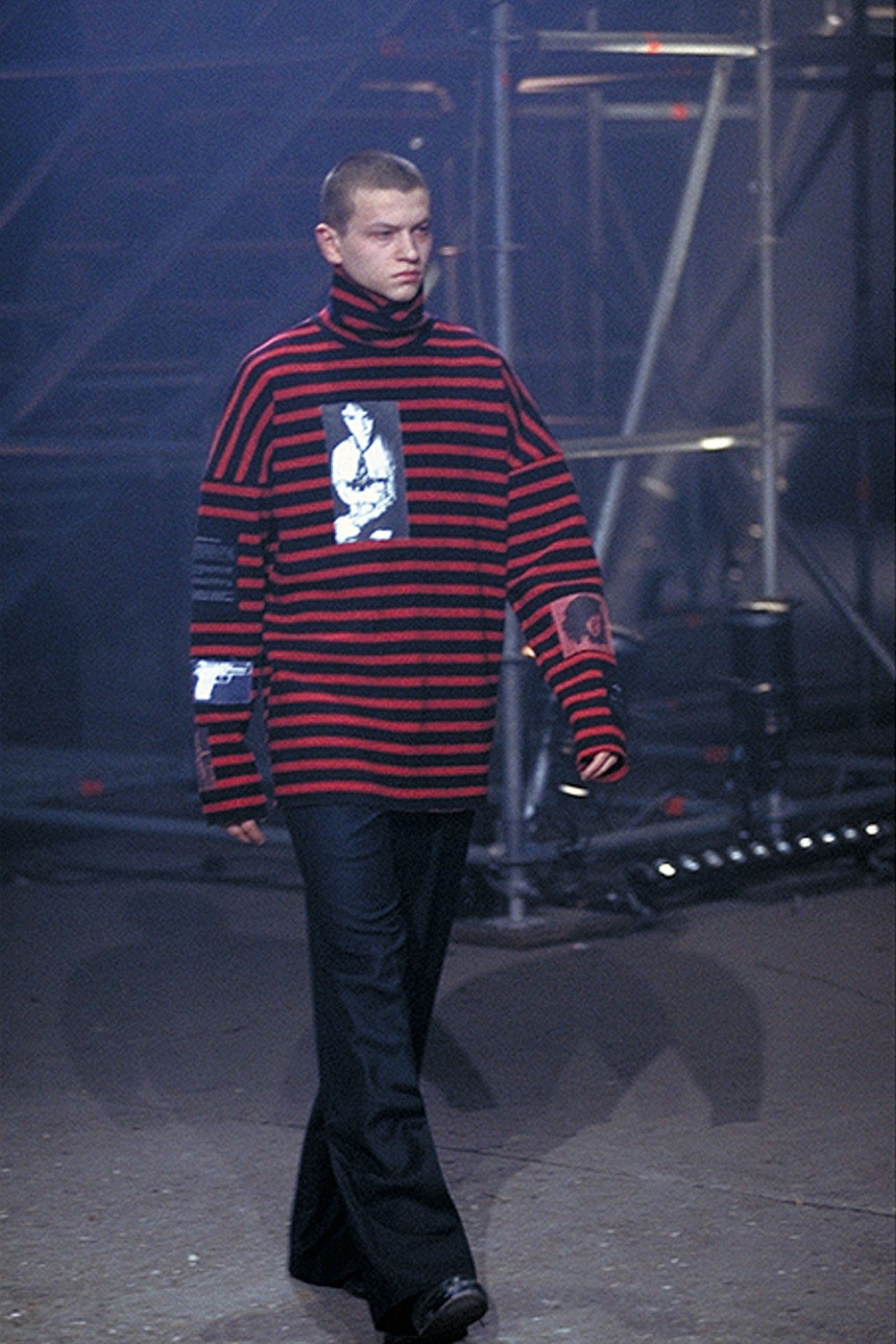

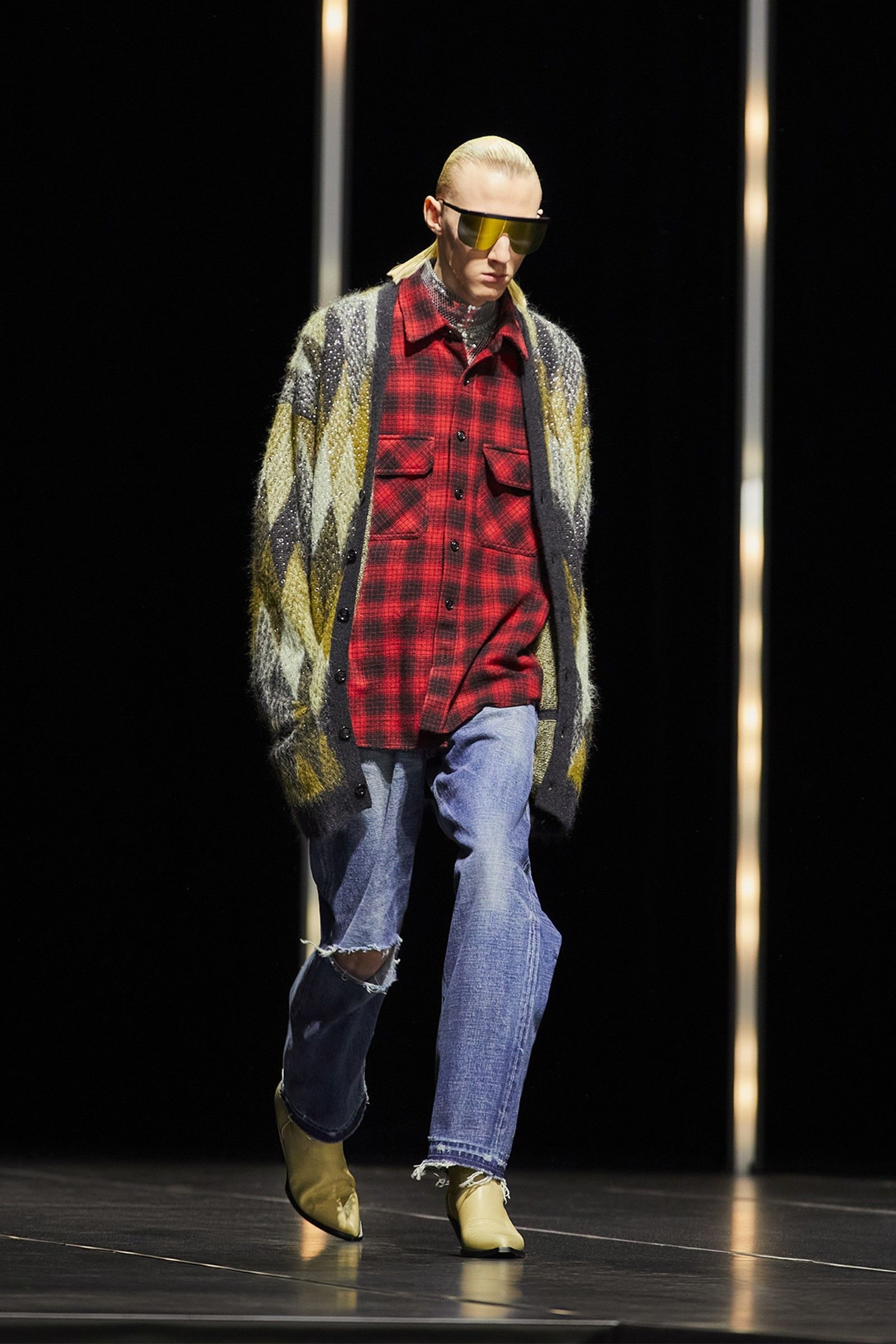

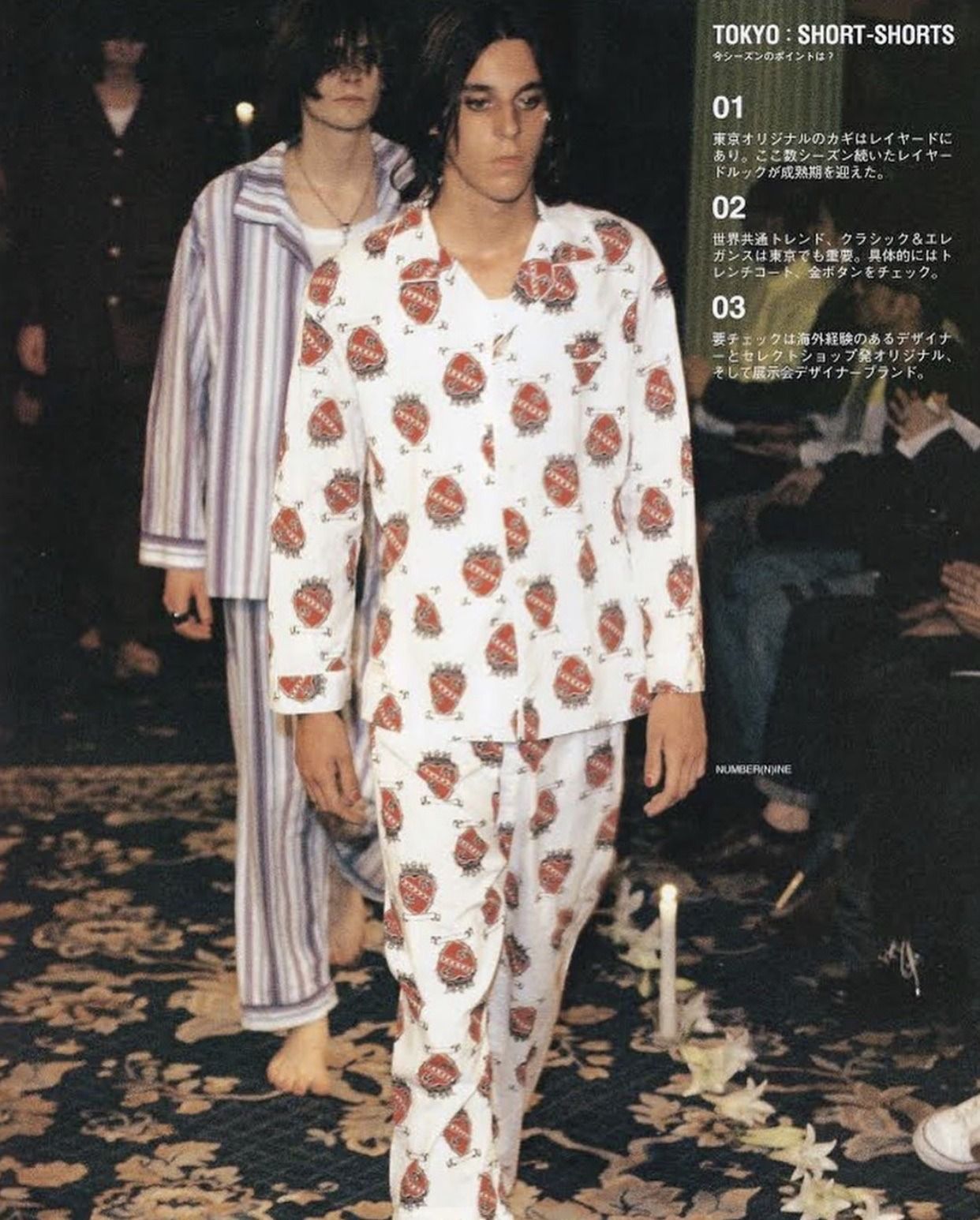

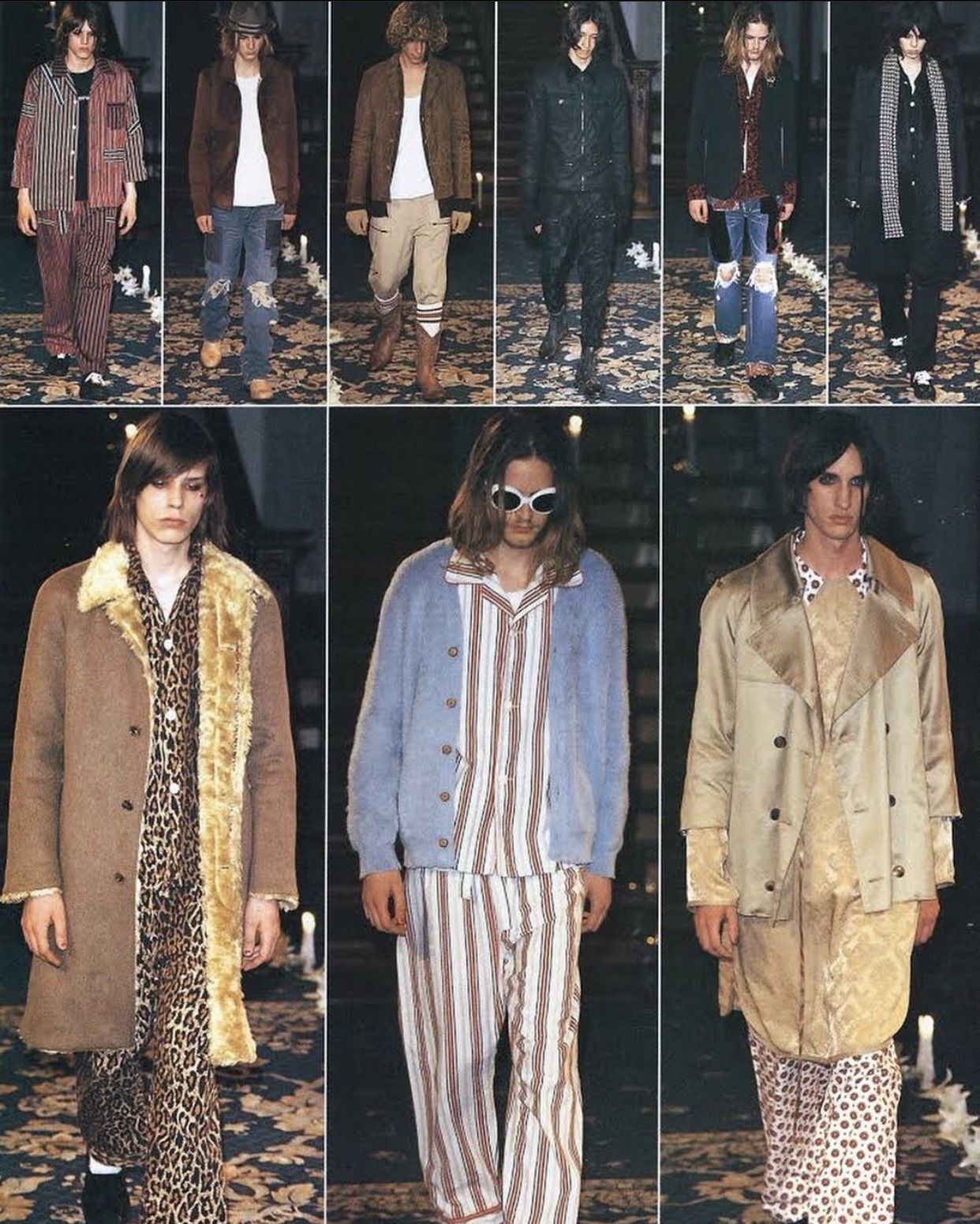

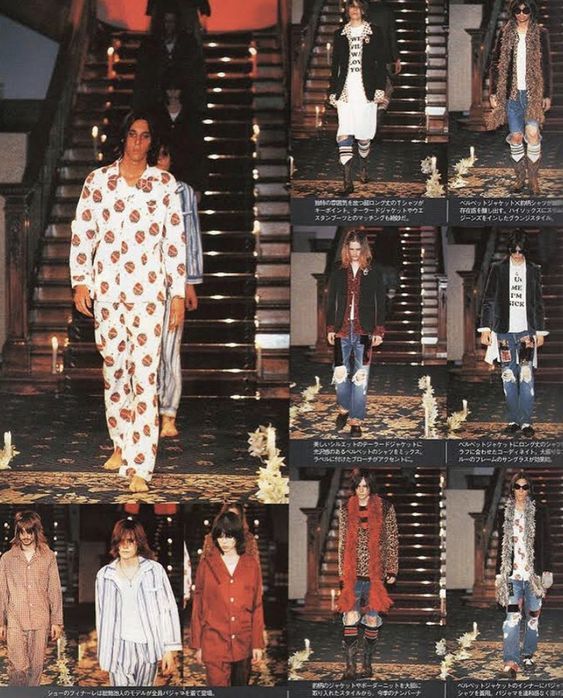

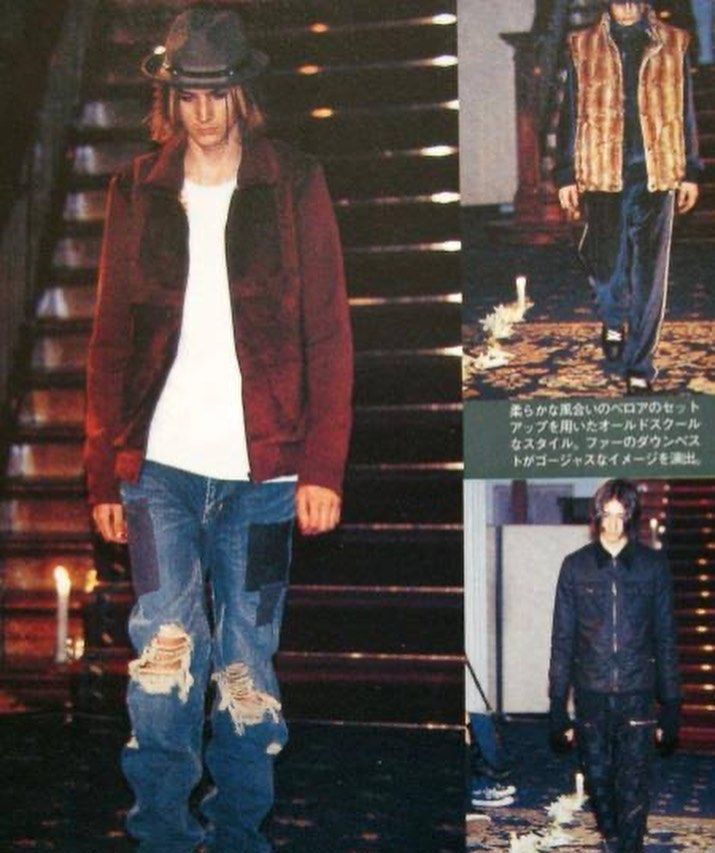

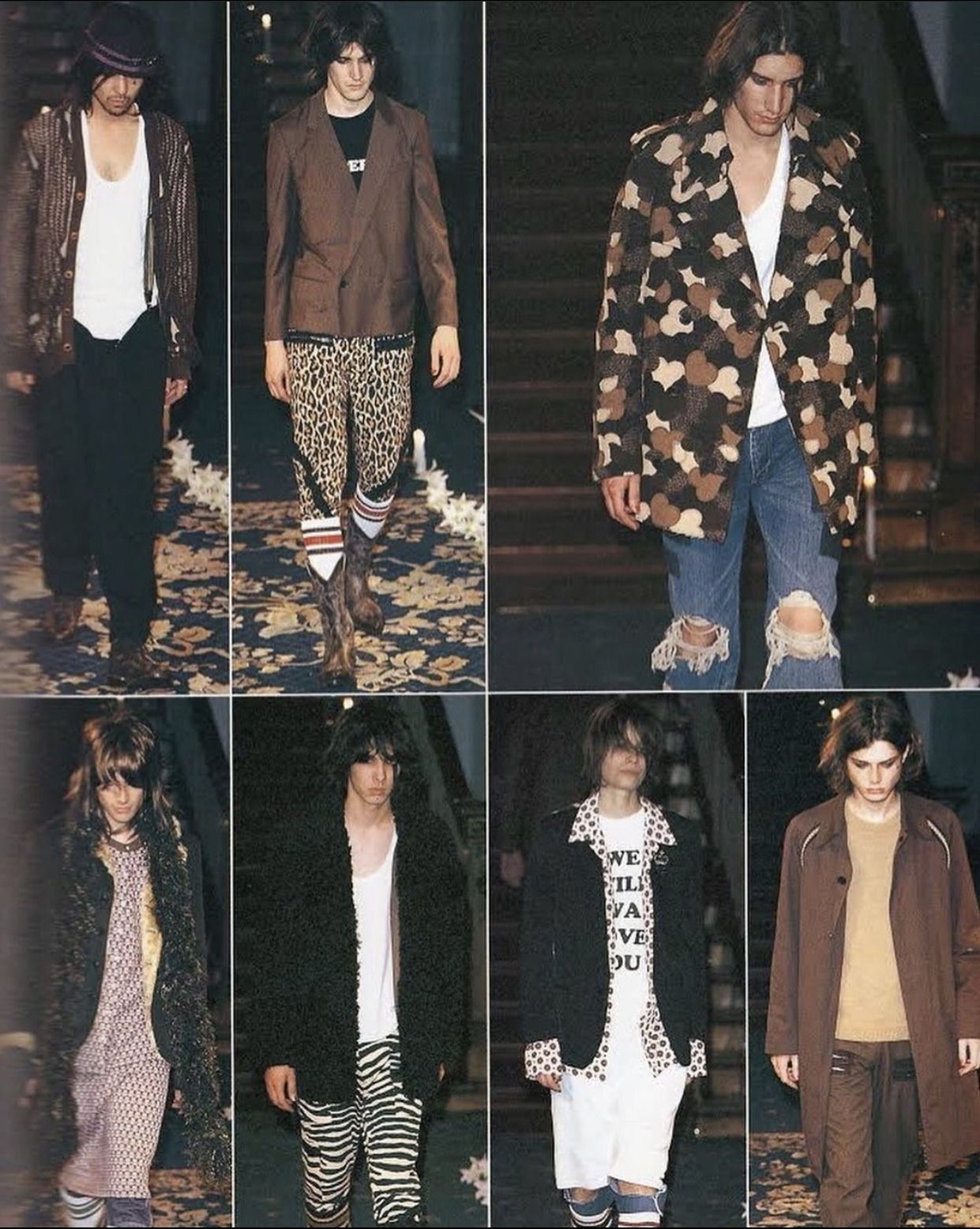

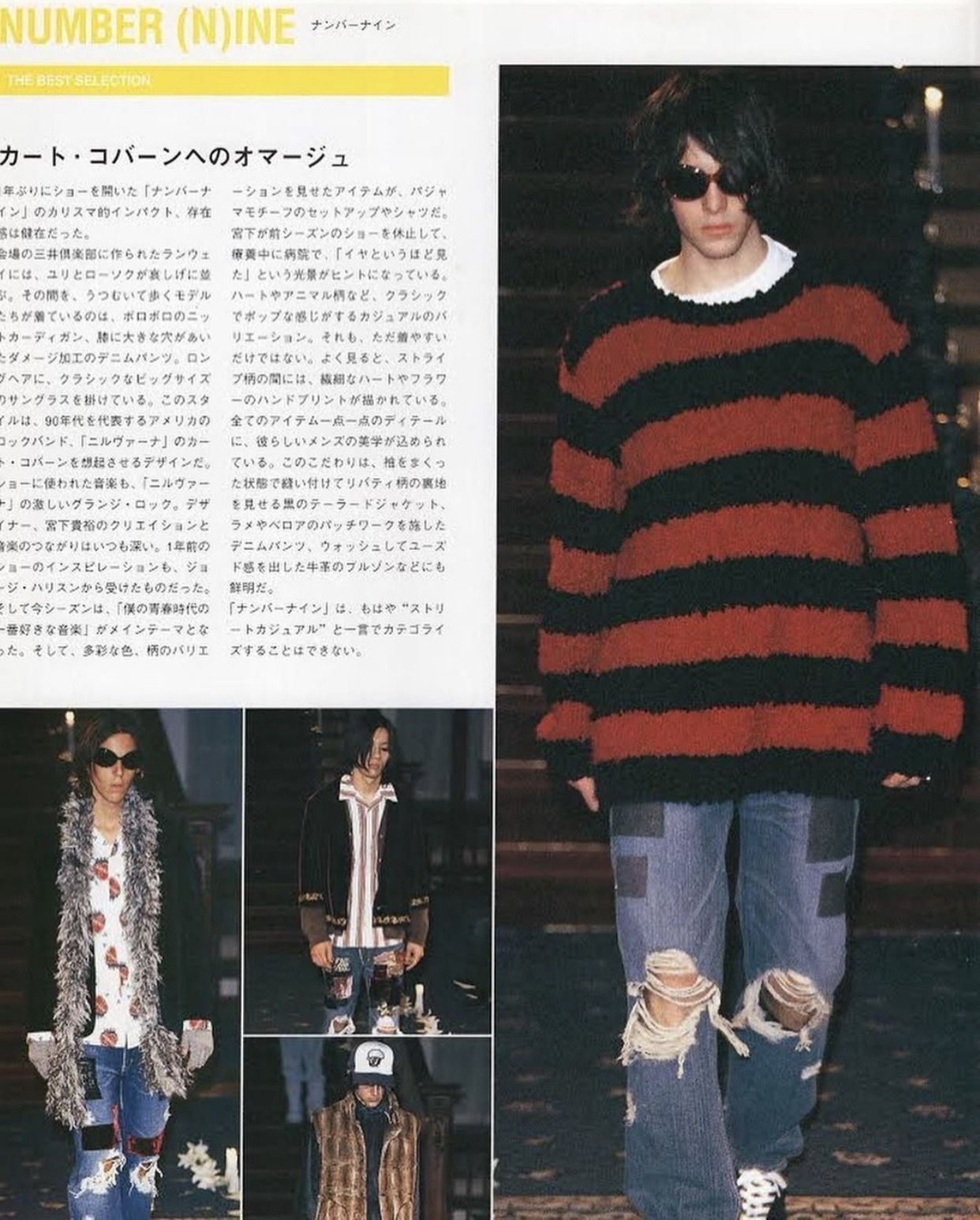

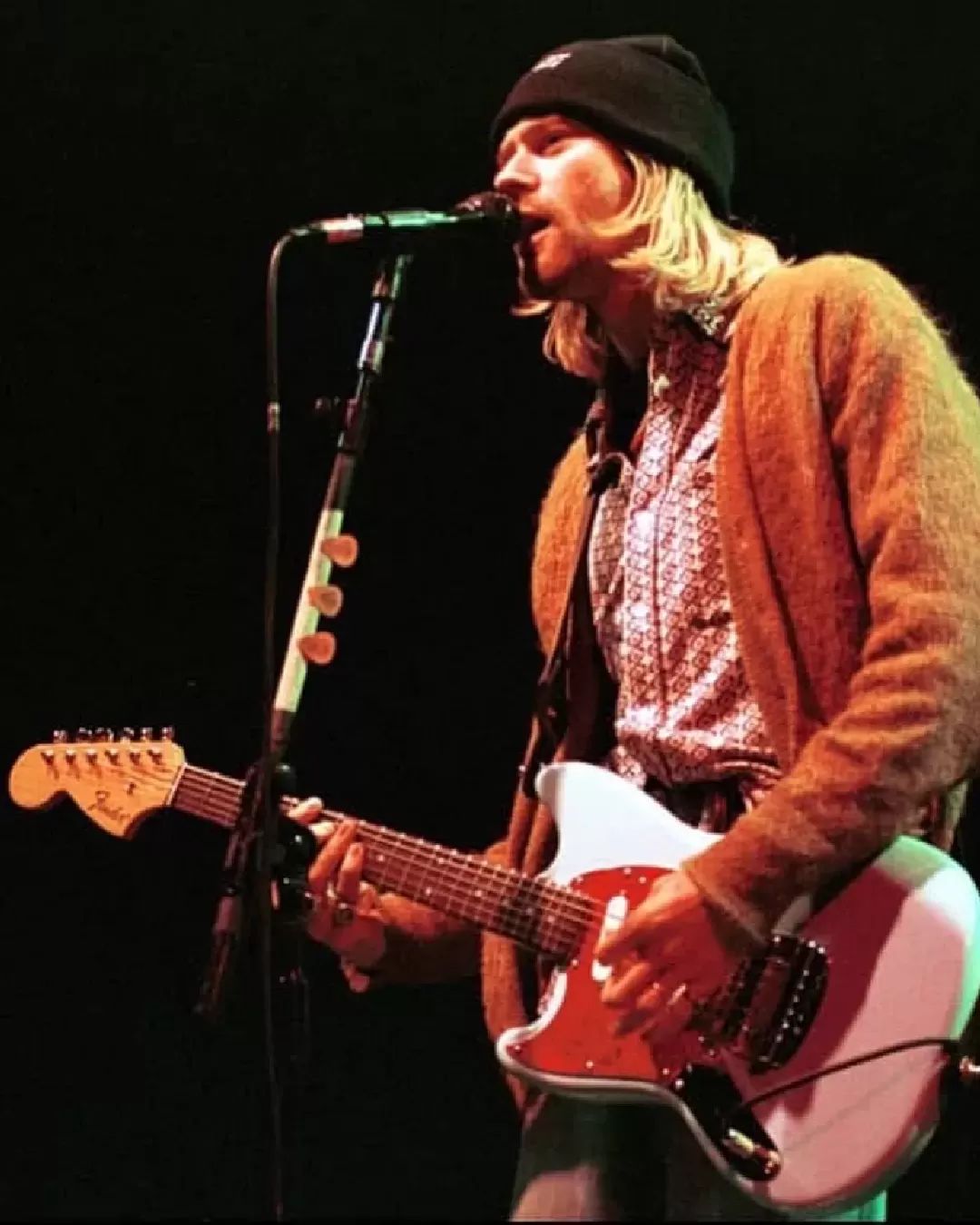

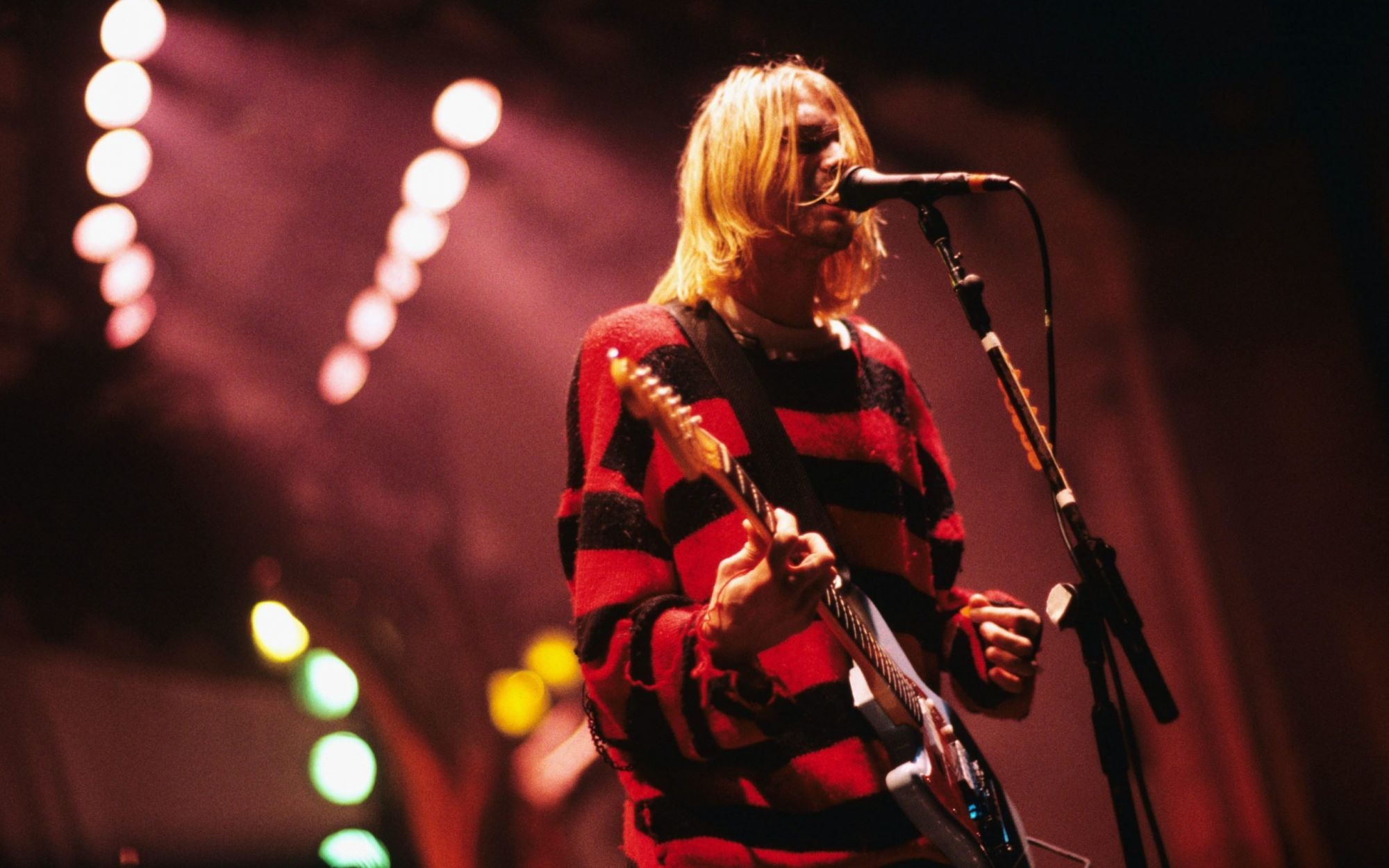

Yet over time, grunge proper has also been a source of inspiration for a handful of designers who have effectively reinterpreted its spirit, even if even the most experienced have not really managed to emancipate themselves from a slavish imitation of Kurt Cobain's personal style. Two famous collections, Number (N)ine's SS03 by Takahiro Miyashita and Saint Laurent's SS16, are perhaps the closest to the actual grunge style - which has since re-emerged in always partial readings by various designers, including Demna Gvasalia who in Vetements' FW19 collection created a perfect replica of the cardigan worn by Kurt Cobain during the legendary Unplugged concert.

Of the many designers who remade grunge, besides Miyashita, perhaps Demna was the one who came closest to capturing the sardonic insouciance of the Nirvana frontman, while it is known that collections such as the famous "grunge collection" designed in 1992 by Marc Jacobs for Perry Ellis was despised by the same exponents of the musical movement. In 2010 Courtney Love told WWD: «Marc sent me and Kurt [Cobain] his Perry Ellis grunge collection. Do you know what we did with it? We burned it. We were punkers — we didn’t like that type of thing». Saying shortly after that, years later, finding some pieces of the collection was semi-repentant of that gesture. «These pieces were part of me and Kurt living in a trench and surviving the war. We just didn't deal with life».

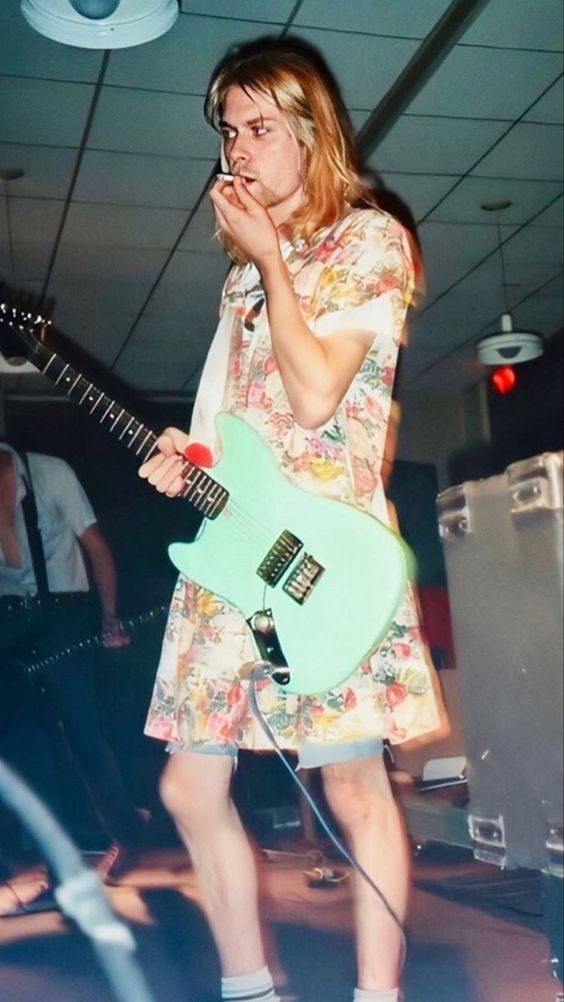

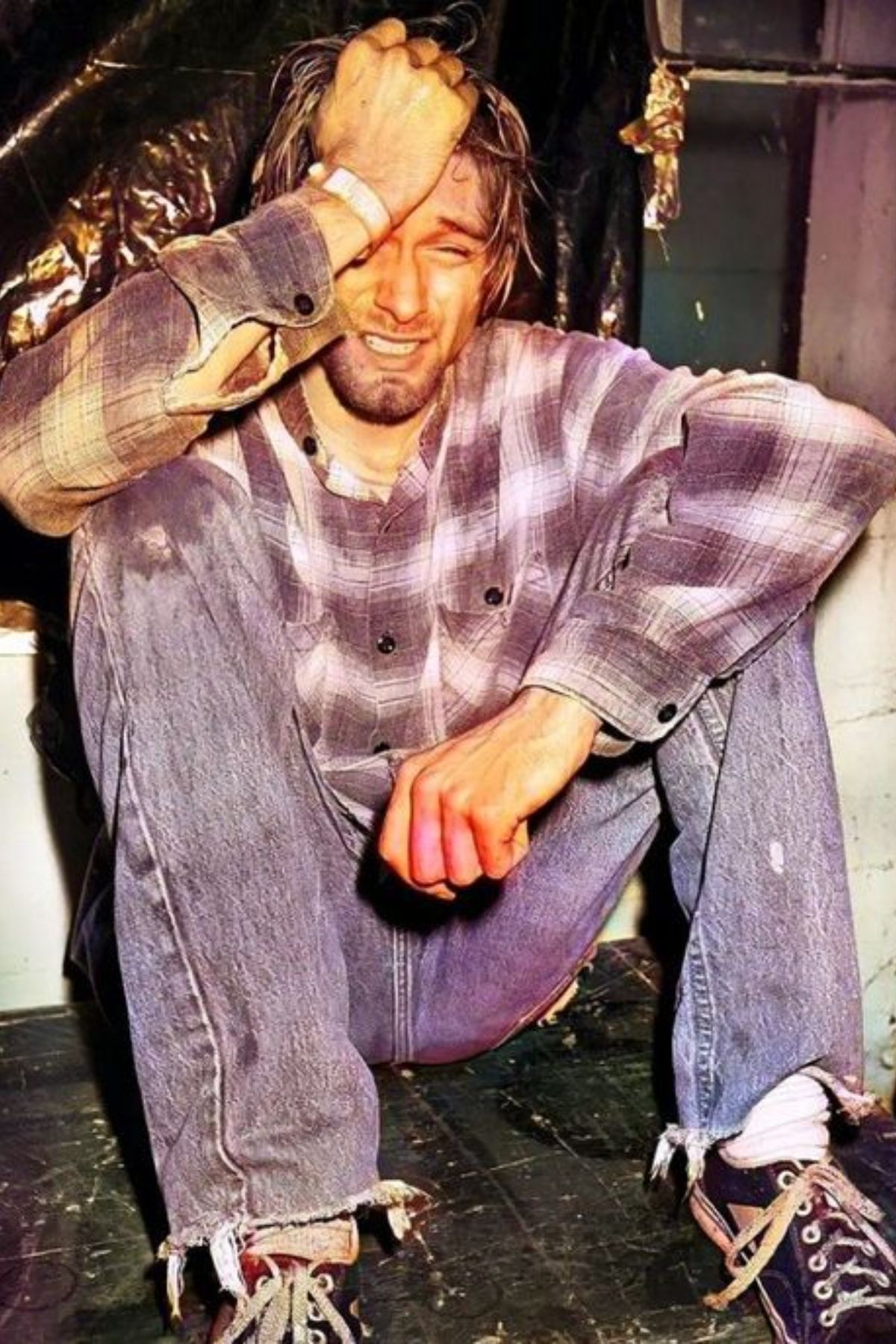

But then what became of grunge? Has the rage of a generation of musicians been flattened to mere moodboards, or has the sense of rebellion inherent in the genre survived beyond its exponents? It has to be said, in fact, that the shock tactics employed by Kurt Cobain and company seem less rebellious now - if seeing Cobain dressed as a woman was a scandal thirty years ago today, fluidity is an almost mandatory requirement for fashion brands. And this is just one example. On the other hand, we can't even talk about a complete detachment between the two worlds, considering the many interesting results that designers have obtained over time replicating and reviving that style. So it's clear that something in the visual vocabulary of grunge still speaks to the public and to the new generations. The issue is therefore of a more abstract nature: grunge has an aesthetic that is so easy to copy precisely because its exponents were not interested in aesthetics - theirs was the fascination with the marginalized and excluded, who would never have adhered to the mechanism of psychological validation at the base of the entire fashion system.

The conflict is therefore about values and opposes, on the one hand, the desire to tap the edginess of the grunge genre for commercial purposes and, on the other, the declared anti-commerciality of the genre itself. A paradox that, at its core, fashion lives using words like "disruptive", "revolutionary", "transgressive" and "anarchic" but specifying a minute later not to advocate the real rebellion but only the generic patina of coolness that comes with it. A paradox that, for example, is expressed in the sale of t-shirts that reproduce the merch of Nirvana at astronomical prices and that Isaac L. Davis described in an article on Archive PDF talking about the grunge collection of Perry Ellis:

«The collection lacked the subversive elements of grunge, in particular the challenging of gender norms, and the willingness to be shocking. […] What made grunge’s style so powerful to begin with was that it stood in opposition to traditional American gender norms and capitalist cycles of consumption. In place of these traditional American concepts, the style associated with grunge offered up do it yourself, recycled garments in conjunction with a complete dismissal of traditional gender norms. […] In this way, [the] show proves to be an excellent example of what usually happens when designers appropriate styles and aesthetics from various cultures. The designer copies the forms of the subculture they are taking ideas from, without actually capturing the essence of said forms and subculture».