The unstoppable run of adidas Original's Gazelles From the Munich Olympics to the catwalks of Gucci and Coperni

The marriage of sportswear and luxury is something we're used to in 2022, yet it was hard to contain the surprise and excitement of the audience when adidas Gazelle appeared on the Gucci runway last month. A surprise and excitement that further grew when a series of vintage adidas Gazelle appeared at the show of Coperni, one of the most appreciated independent brands of Paris Fashion Week, and also of Wales Bonner who renewed his collaboration with adidas for the new collection. The skateboarding world has also recently shown its love for the classic silhouette: in January Blondey McCoy presented his re-design of the sneaker, as did Theo Constantinou of Paradigm and Mark Suciu in recent months.

Why are adidas Gazelle trending right now?

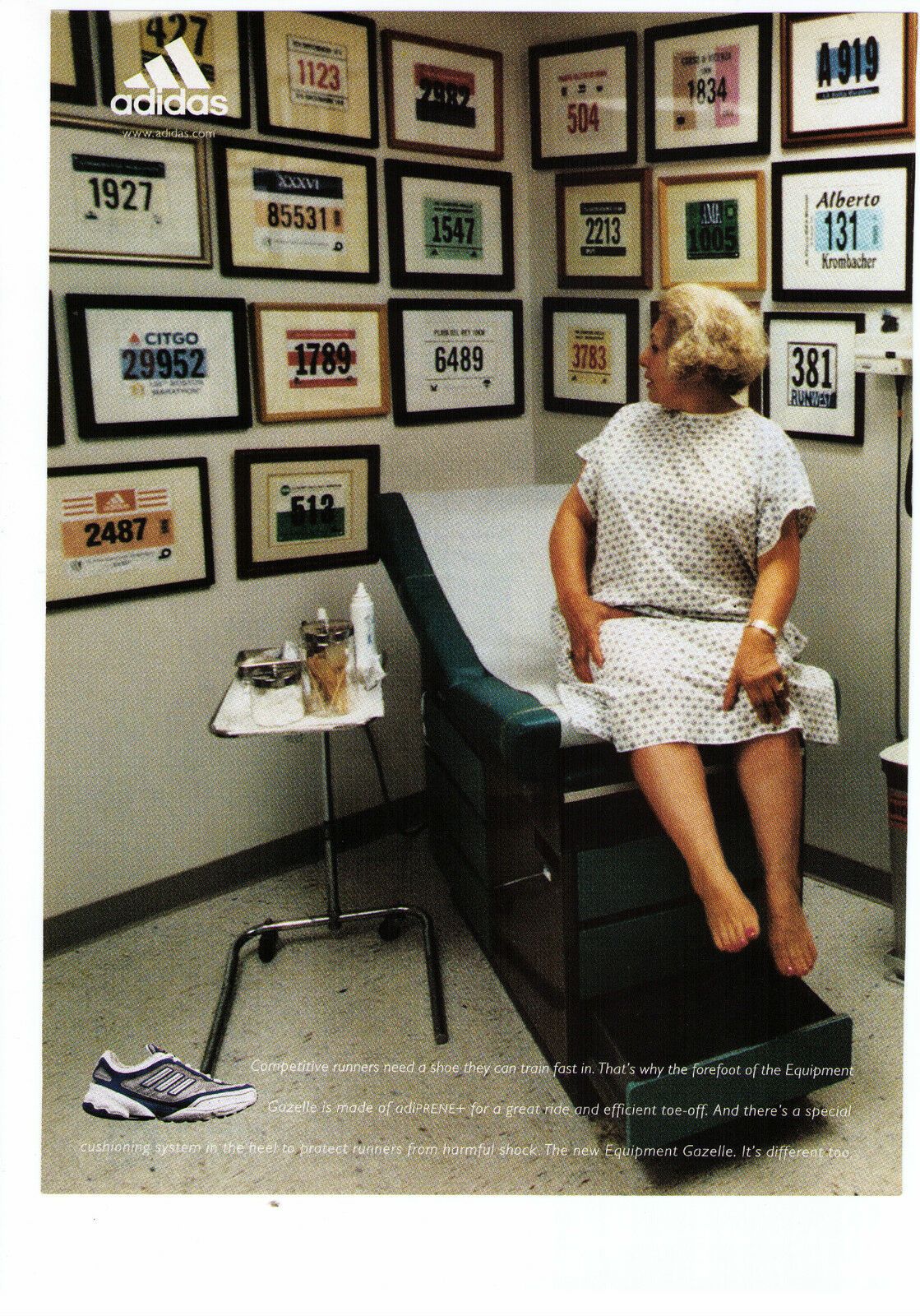

The success of the sneaker actually lasts for years and last August, in an interview with Hypebeast, the Advanced Concepts Footwear Designer at adidas, Jean Khalife, tried to explain its appeal:

«I’ve always thought that the Gazelle is an “outsider.” It’s an iconic adidas shoe for sure, but not the first one that you’d think of like the Stan Smith or the Superstar might be. It’s a bit more niche, and a bit of a paradox too: it’s a very accessible, democratic sneaker, but not everyone has a pair — so wearing it still makes you feel special. […] From a design standpoint, I just love the quality. A full suede upper that takes colors amazingly, a funky, sort of ‘70s vibe».

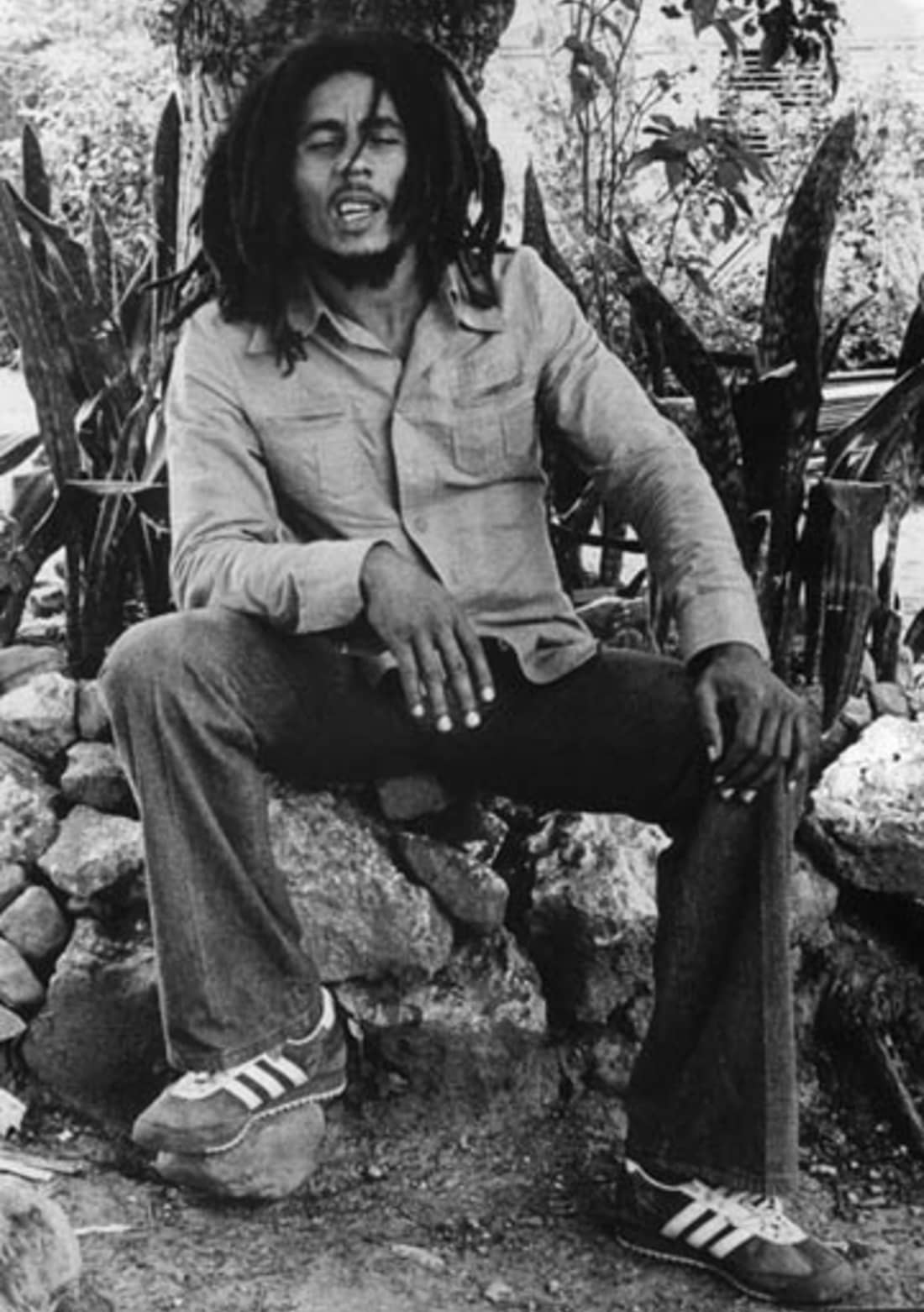

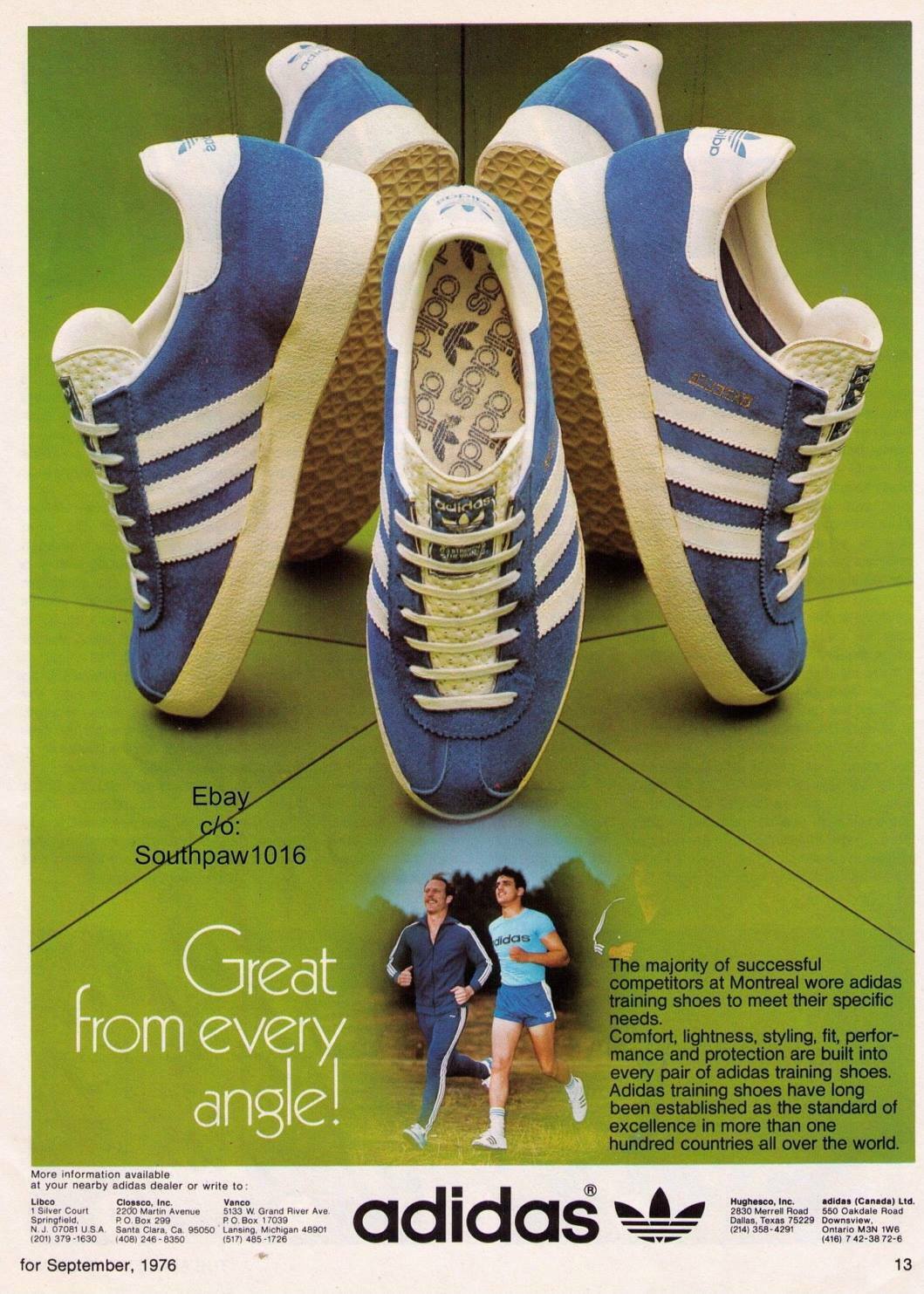

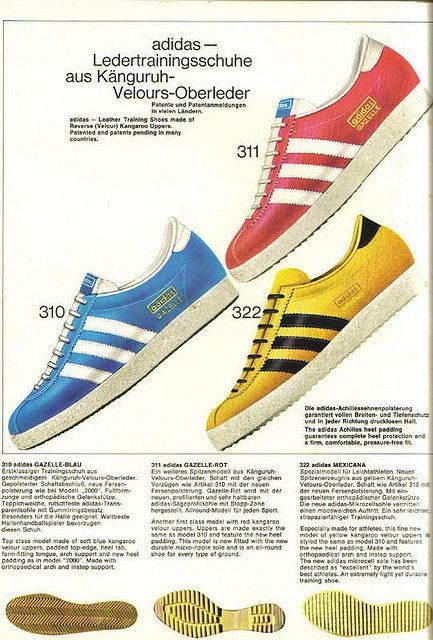

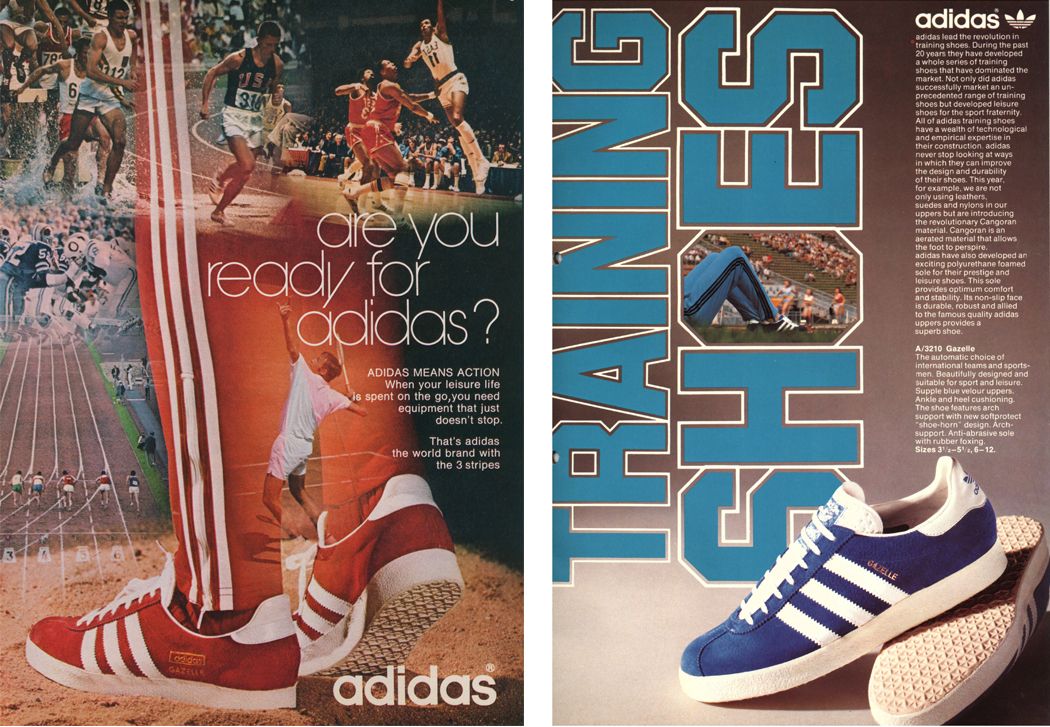

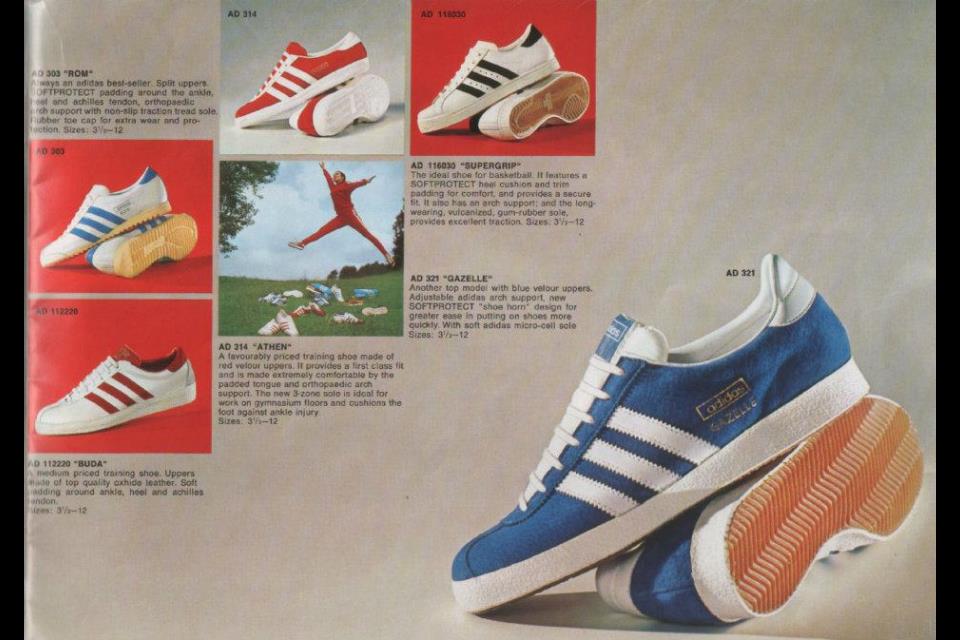

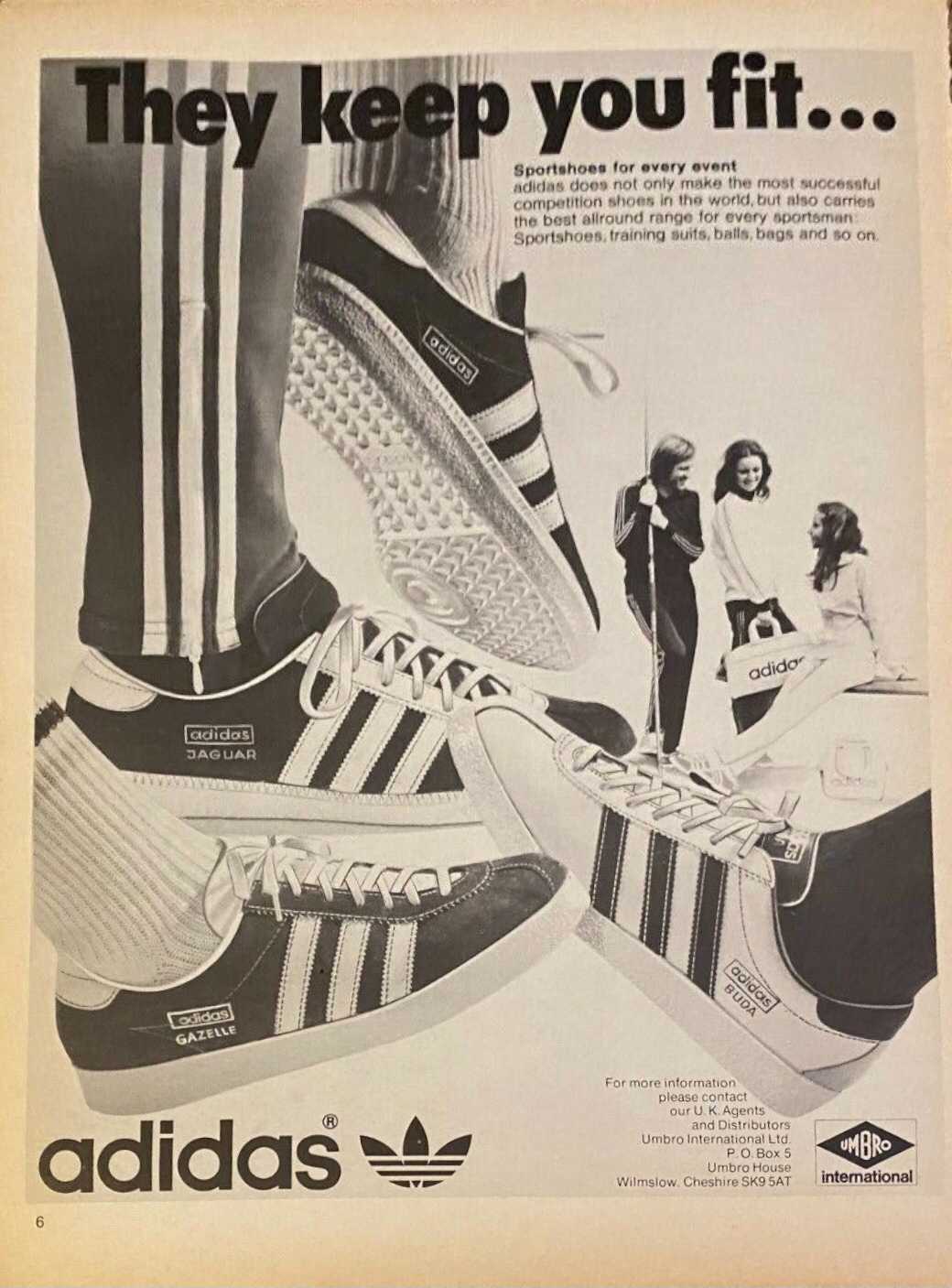

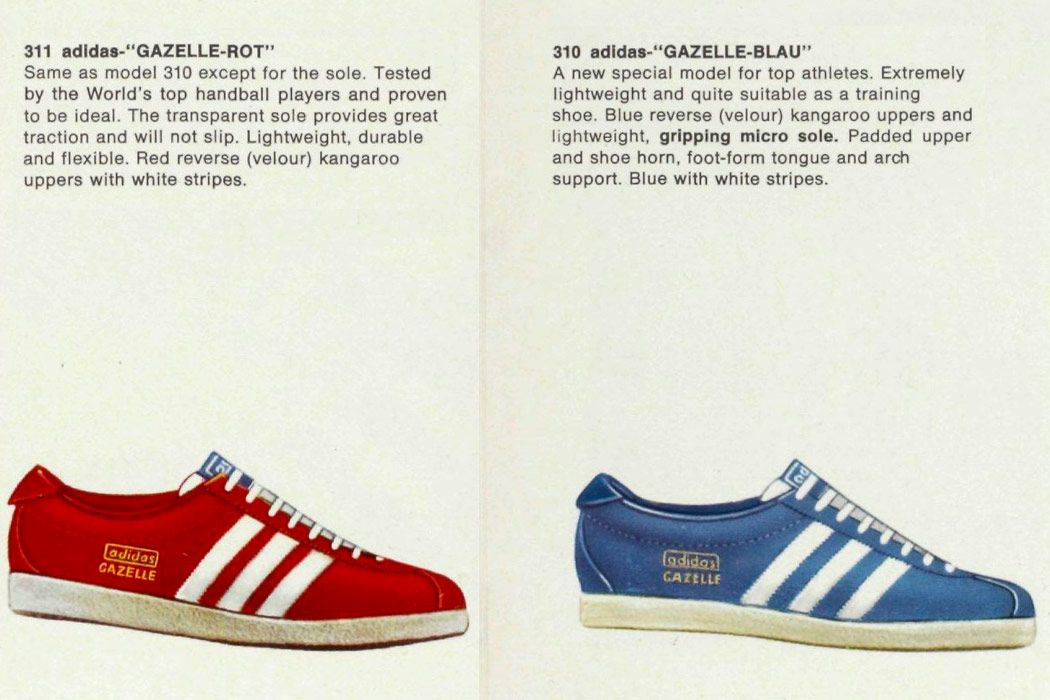

That very '70s vibe is probably what made the Gazelle collaborative co-signed with Gucci so successful - but the truth is that the sneaker possesses a fairly stainless vintage aura due to the fact that the original design, which dates back to 1966 though, has essentially remained unchanged despite the fact that various iterations of the silhouette have tweaked and updated it over time. The Gazelle was designed on the blueprint of another sneaker, the Rom, created for the German Olympic team at the 1960 Rome Olympics. A suggestive version of the facts reported by Neil Selvey, however, wants the name of the sneaker to come from the American centimeter runner Wilma Rudolph, who wore adidas when she won gold at the Rome Olympics earning the name "Black Gazelle". In any case, as Selvey notes, Rudolph retired from competition two years later, and that is before the official debut of the sneaker in '66 and so perhaps his figure represented an initial inspiration for the sneaker - which by the way was released at a time when adidas baptized its models with names of very fast animals such as Panther and Jaguar. The two original models were color-coded, as Jean Khalife explains: «Blue Gazelles were for indoor training, red were for outdoor training».

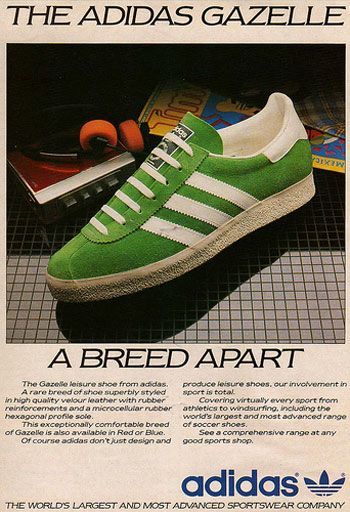

Many point to the suede construction (originally kangaroo suede) as the main novelty trait of the Gazelle, which was both more flexible and lighter than leather but still durable enough to withstand physical activity. The suede upper, however, served not only a practical function but an aesthetic one: the material tends to absorb color better by virtue of its porosity and thus allowed for a much greater range of colorways at a time when the rest of the sneakers were leather. Gary Aspden, adidas consultant and head of the brand's Spezial line, also confirmed the fact to Complex in an interview: «At their time of release, they pushed the envelope on color when it came to training shoes. The dyed suede was far more vibrant than colored leather». To state that it was with the Gazelle that the more properly aesthetic discourse entered sneaker culture would be radical - but surely the silhouette extended and expanded the concept of colorway, paving the way for constructions with numerous different materials and the idea of colorway as we understand it today.

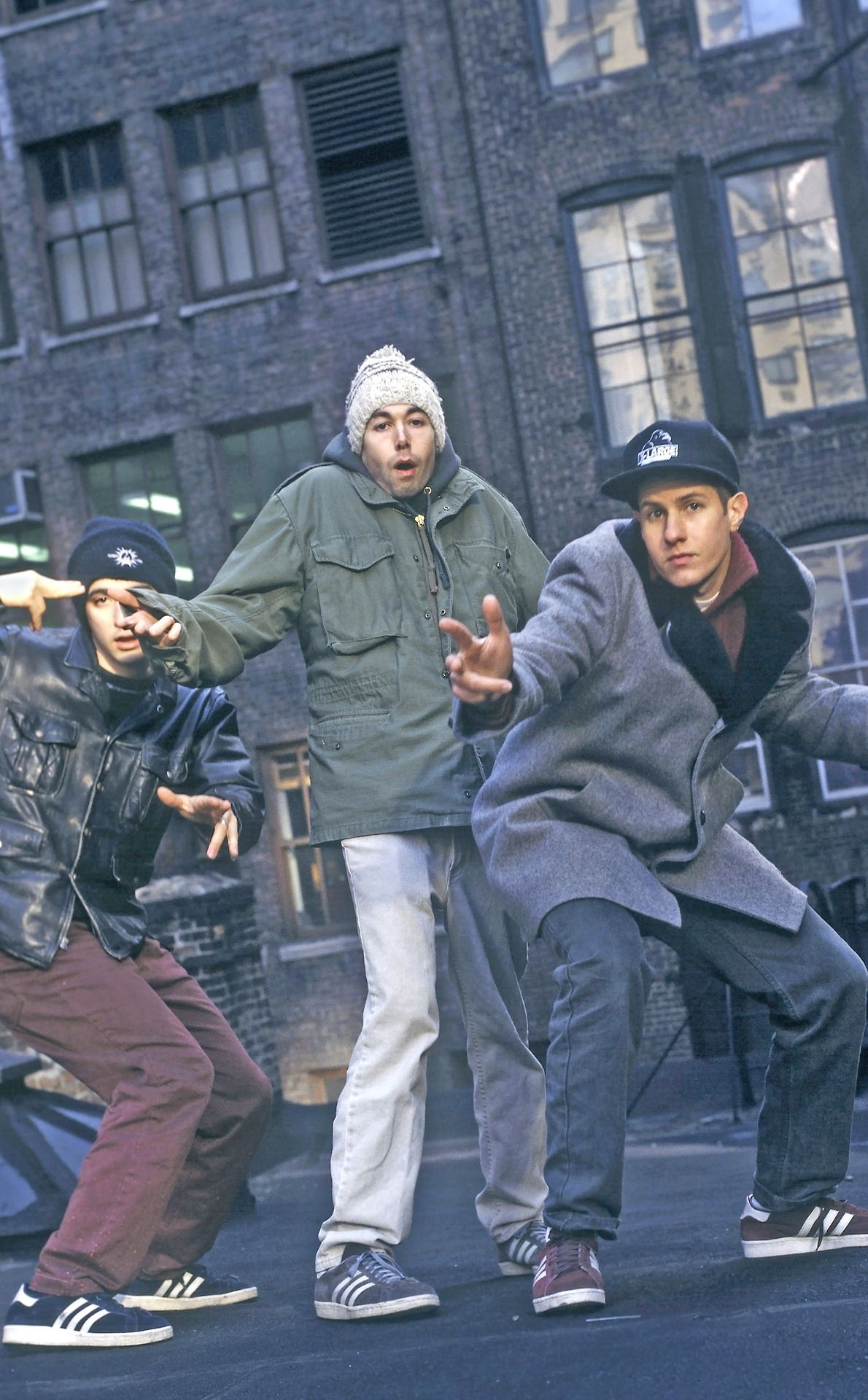

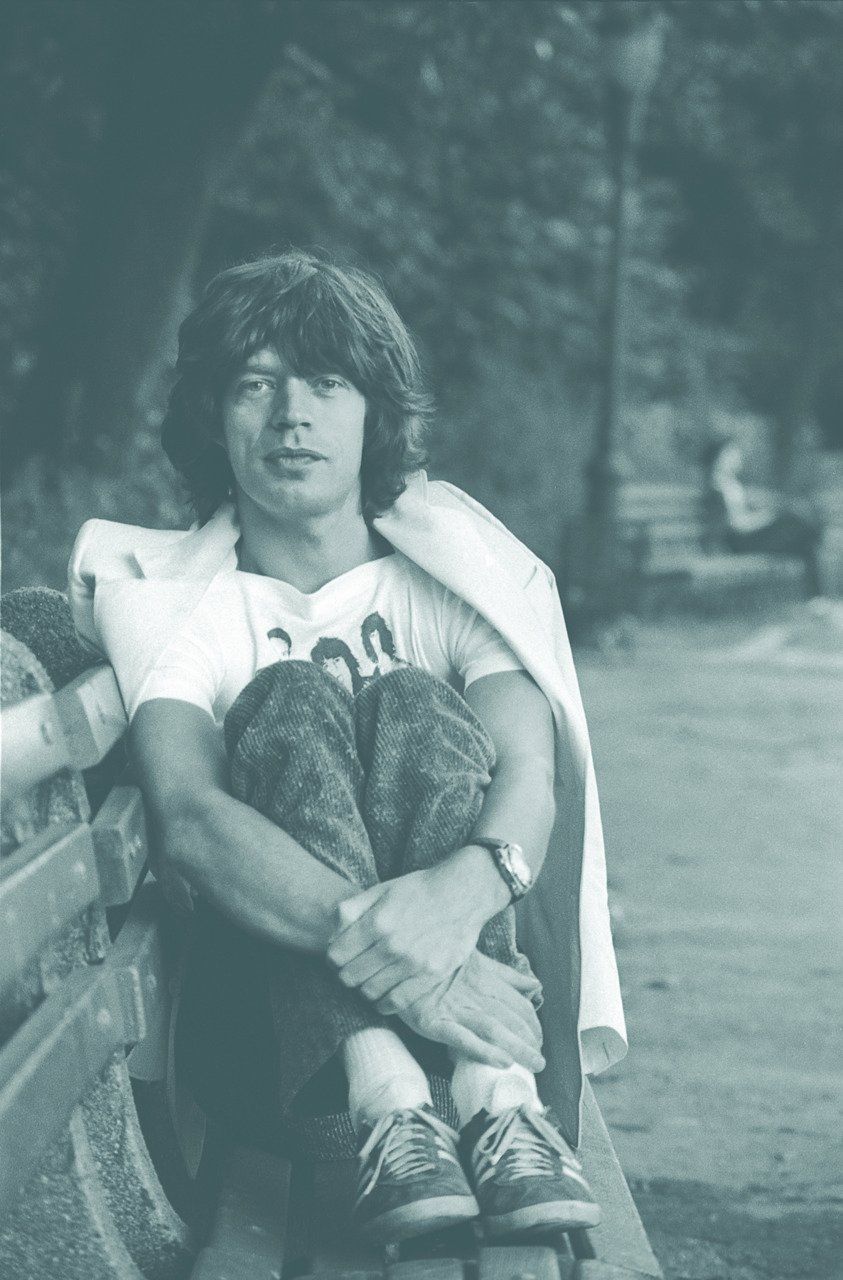

In the 1970s the perception of the model went through a metamorphosis: in '72 the Olympic swimmer Mark Spitz celebrated his triumph at the Munich Olympics by holding his Gazelle aloft during the performance of the national anthem, attracting a strong controversy; in '73 the model-sosia of adidas Jaguar supplanted the Gazelle on which, however, the entire City Series of the brand was based in the future; in '76 the Gazelle appeared on the pages of the legendary Japanese magazine Popeye that cemented its status in the emerging fashion scene of Tokyo pre-Harajuku and, in '79, the shoe had a reissue under the name of Gazelle Special. In the '80s, however, through the spread of hip-hop music in the UK and its fusion with the football-centric style of hooligans, the Gazelle became a central element of youth clothing, enriching itself with a new colorway, and then expanding its presence across the breadth of the urban scene: from breakdancing to skate, from hip-hop to the world of basketball.

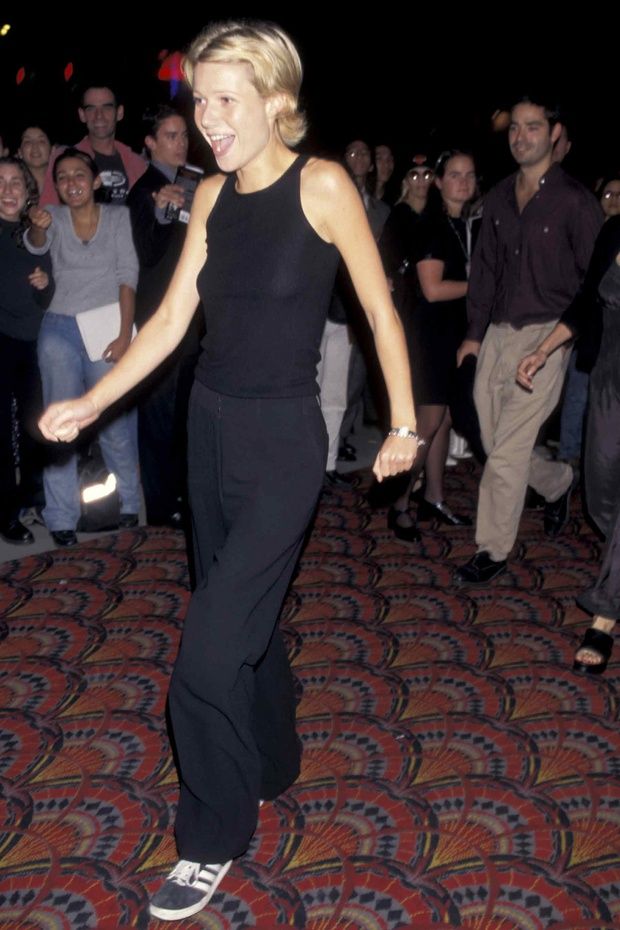

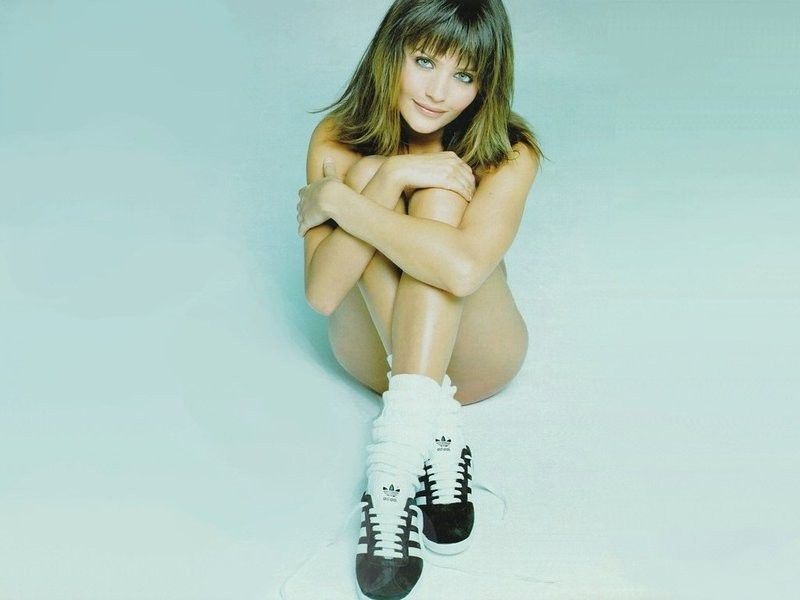

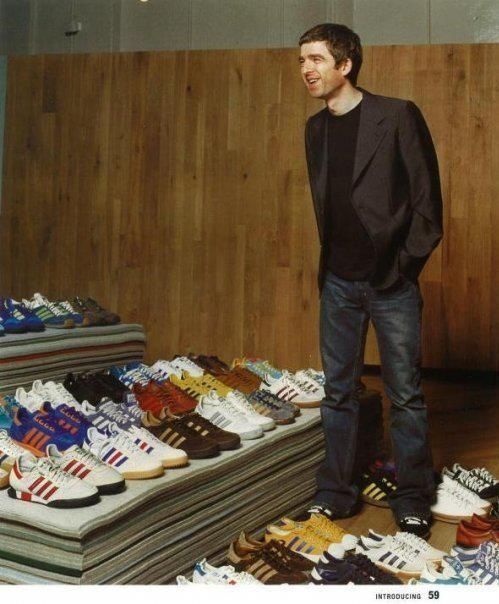

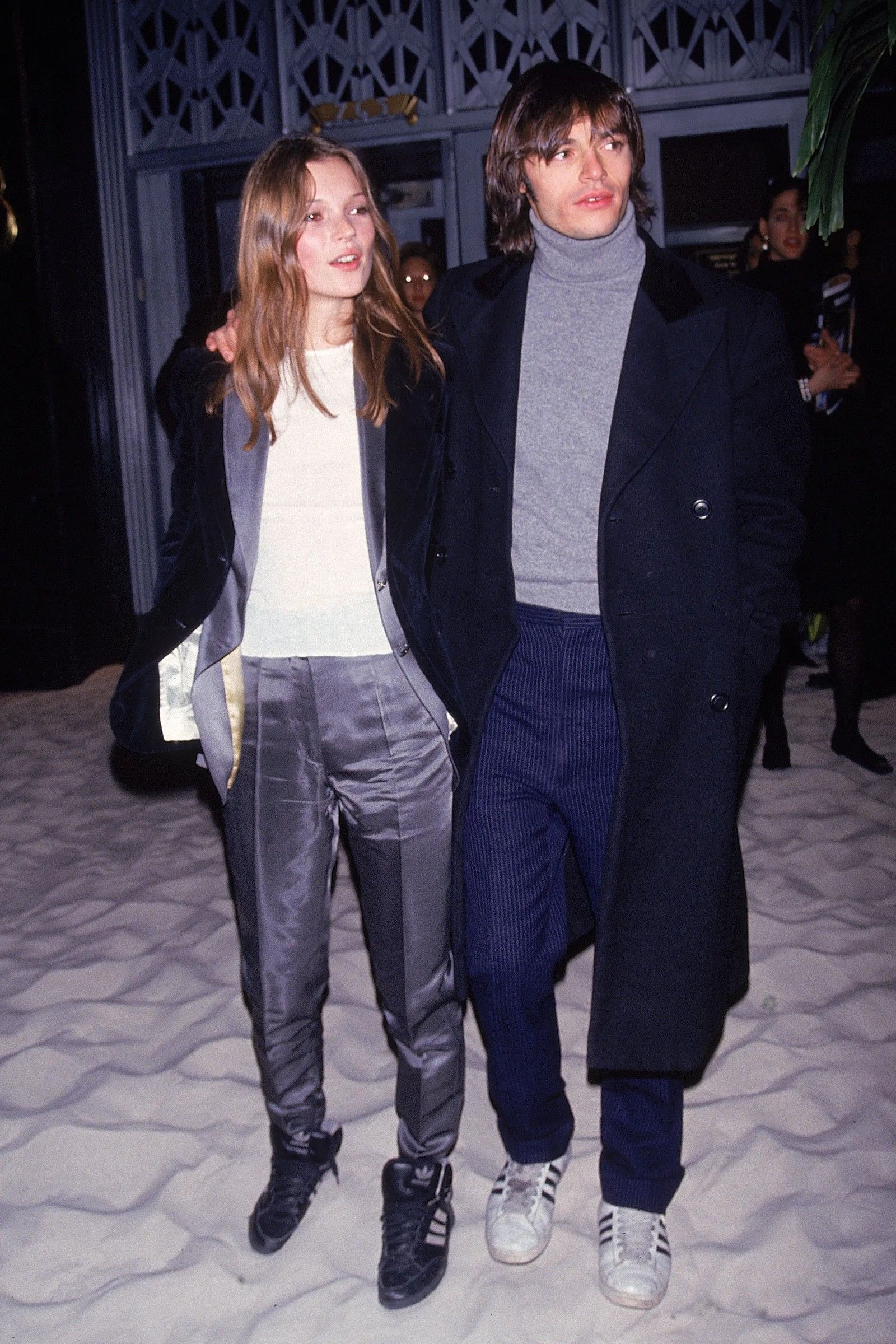

This diffusion prepared the ground for the '90s, when from the soil of hooligan culture blossomed the flower of Britpop: Oasis and Blur included the Gazelle in that glossary sportswear that would become part of the language of streetwear twenty years later. Meanwhile the nascent legion of supermodels adopted Gazelles as sporty, disengaged shoes for when the heels of the catwalk became uncomfortable. It was the ultimate coronation of the Gazelle: cool kids halfway around the world were wearing them, the shoes were colorful yet minimal, evoked the world of American and European subcultures, and most importantly, they were accessible in many markets and for every audience. Their success was the success of a democratic design that, starting from the hyper-athletic inspiration of the origins, discovered that sportswear could become the fuel for a completely different phenomenon, that from sport borrowed the social dynamics of the group and the popularity among the new generations but that transcended the idea of simple athletic performance to approach self-expression and a new language of dress. It was precisely the Gazelles of this period that were replicated in 2016 during the relaunch of the silhouette. Again Gary Aspden explained to Complex the phenomenon this way:

«I was saying how to someone how the Gazelle has overtaken their original purpose and function and how no serious athlete would use a shoe like that to train in, and then I remembered seeing James Bond working out in a pair in one of the recent Daniel Craig films. If they are good enough for James Bond to use in the gym, then who am I to argue otherwise?»