Why we need to modernize the figure of the creative director In 2022, fashion needs above all horizontality and transparency

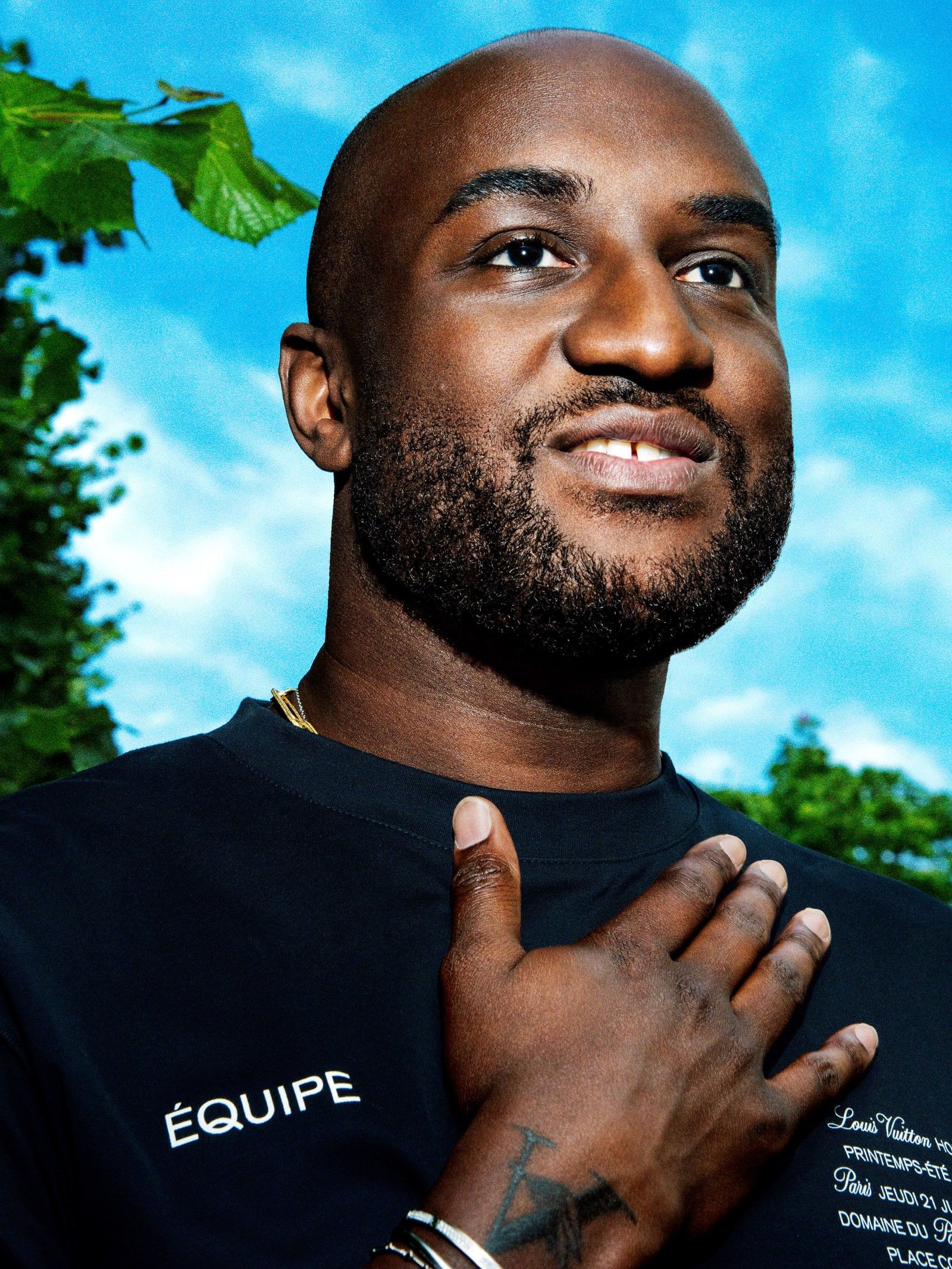

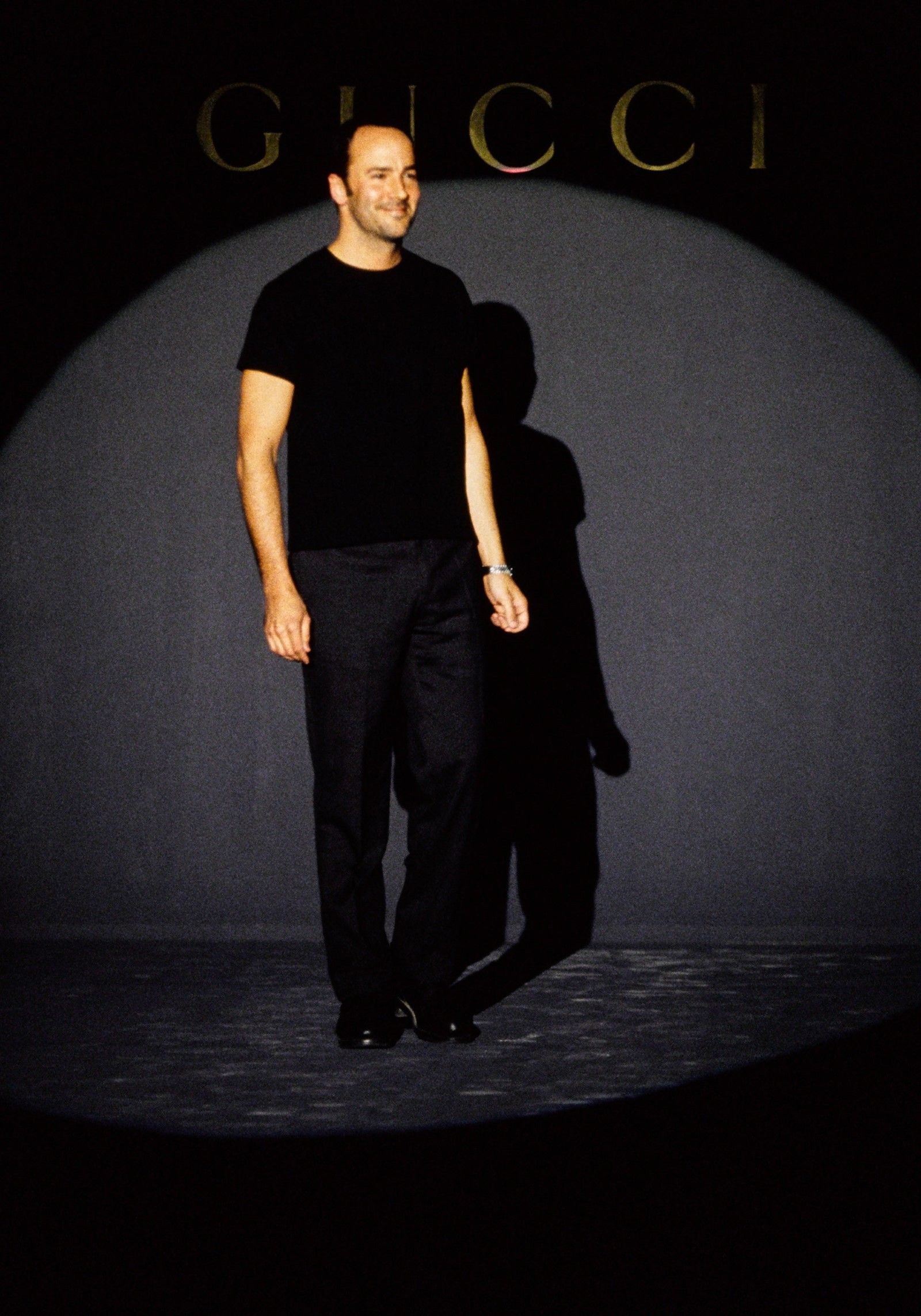

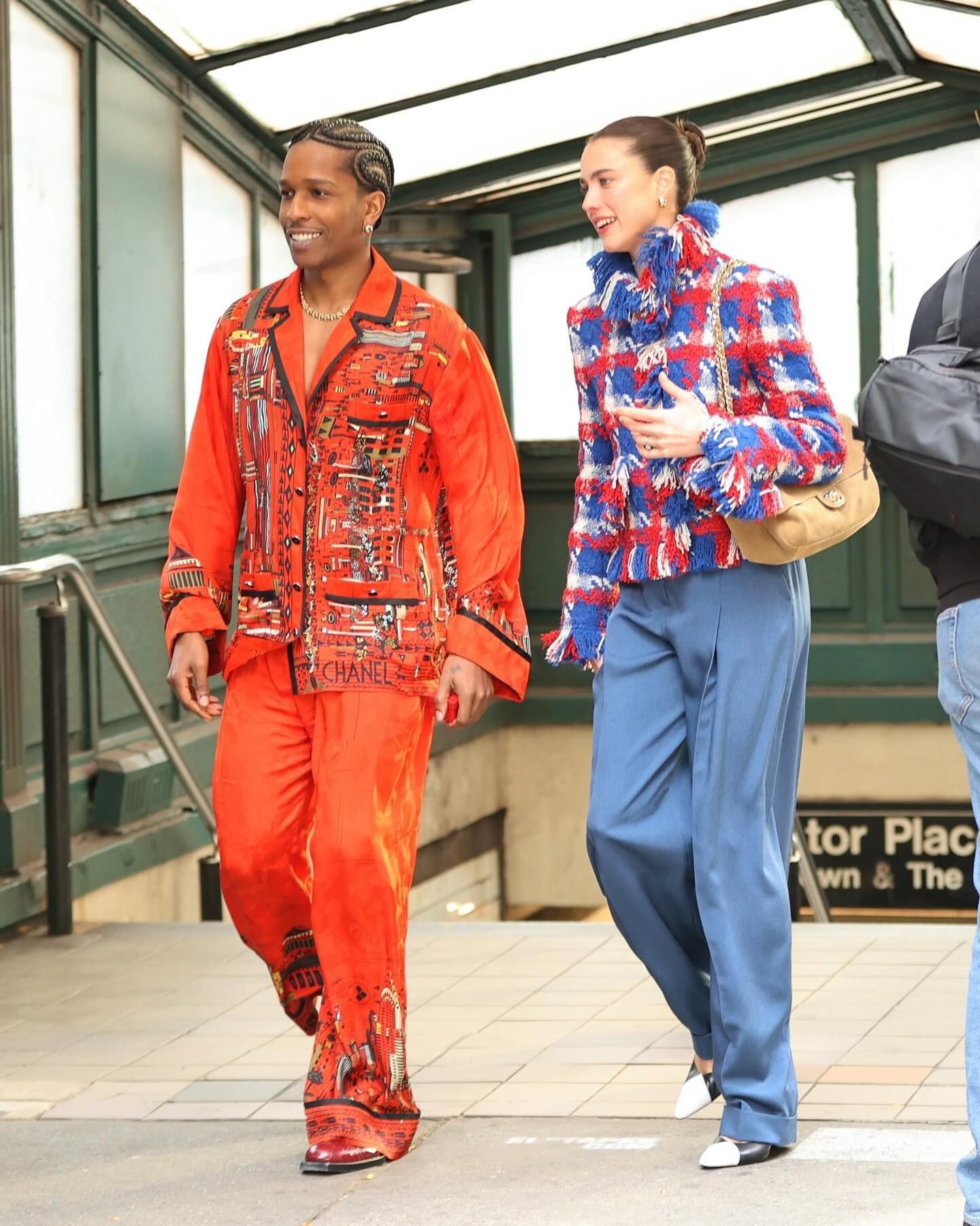

Some time after Daniel Lee's departure from Bottega Veneta, wanted or unwanted, meditated or happened suddenly, we can take some time to reflect on why the sense of the tragic in the fashion world has been expressed so often through the figure of the creative director and why the narrative surrounding the sector would do well a greater balance. We have all learned from House of Gucci how Tom Ford, the first person ever to embody this role, arrived at a time to say the least disastrous for the brand and decreed its rebirth but many also remember a John Galliano, then head of Dior, who, visibly drunk, shouts anti-Semitic insults to some patrons of his favorite bar and then is chased away sitting still and sent by Anna Wintour to a rehab. The sense of the tragic (not that of Nietzsche but that of cheap tabloids) is manifested through figures so powerful from a communication point of view that the recent death of Virgil Abloh has thrown masses of acolytes into despair, leaving them apparently without a point of reference, depriving them of a figure that was and still is an icon in their own field. This is because the story of the brands today travels around and through their supreme boss, heart, mind and soul: the untouchable creative director.

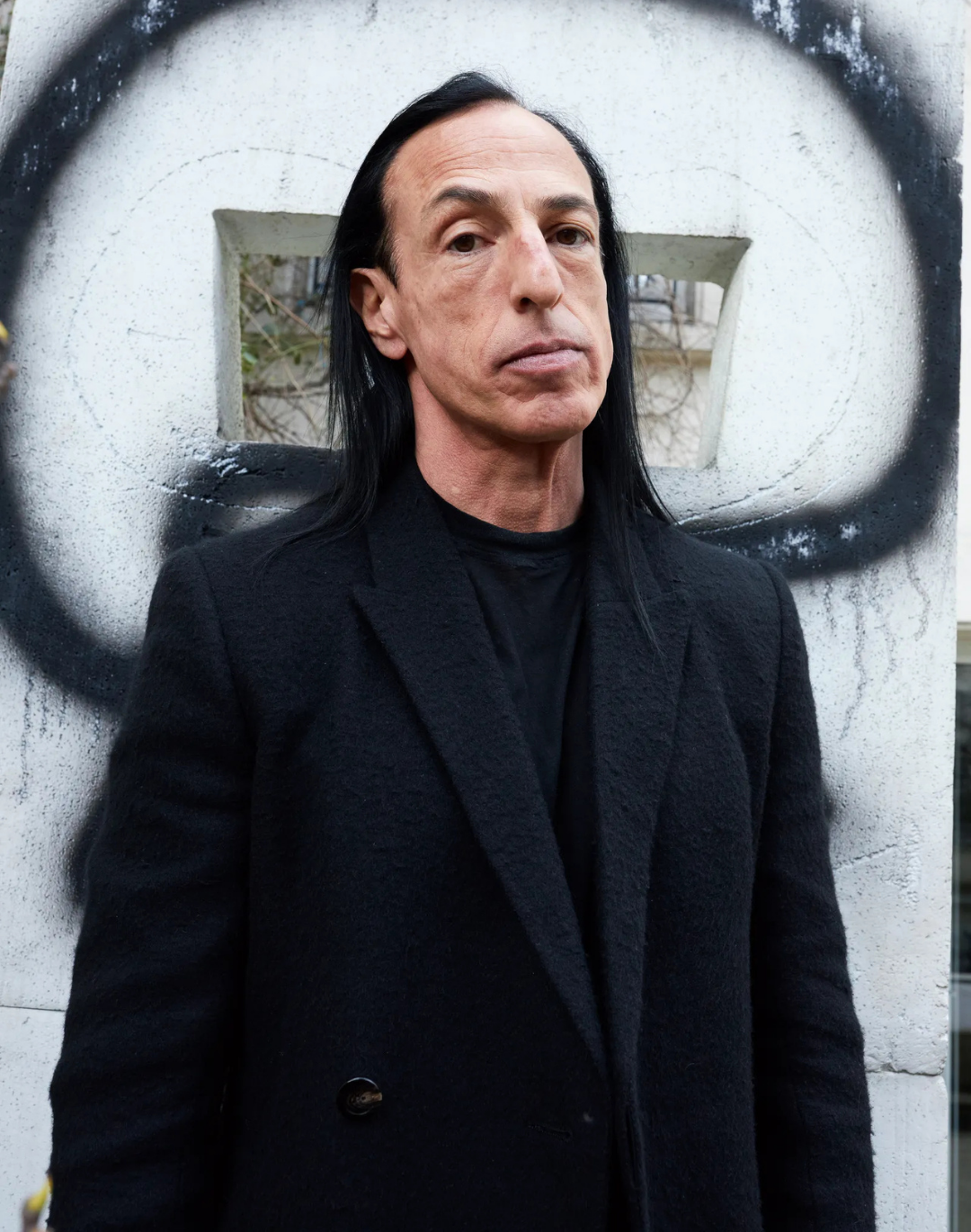

Creating a pyramid of power with somebody always on top, however, means completely ignoring the very modern concept of horizontality, concentrating all the pressure on a single person and consequently, most likely, creating an unhealthy environment. Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, the world's largest hedge fund with a personal fortune of $18.7 billion, in his book The Principles of Success tells how its wealth is due to a corporate culture based on radical transparency, in which everyone can express an idea and this idea can become reality if accepted through open and engaging decision-making processes. Not exactly what comes to mind when we think of Miranda Priestly of The Devil Wears Prada, an absolute negative benchmark but in reality a constant reference point for many creatives at the head of more or less famous brands.

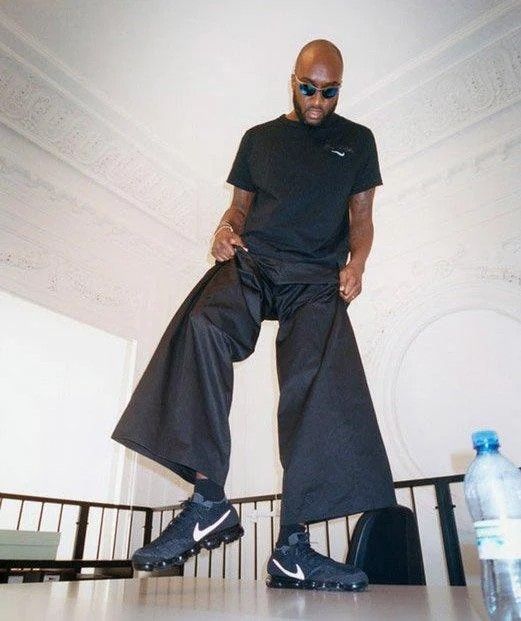

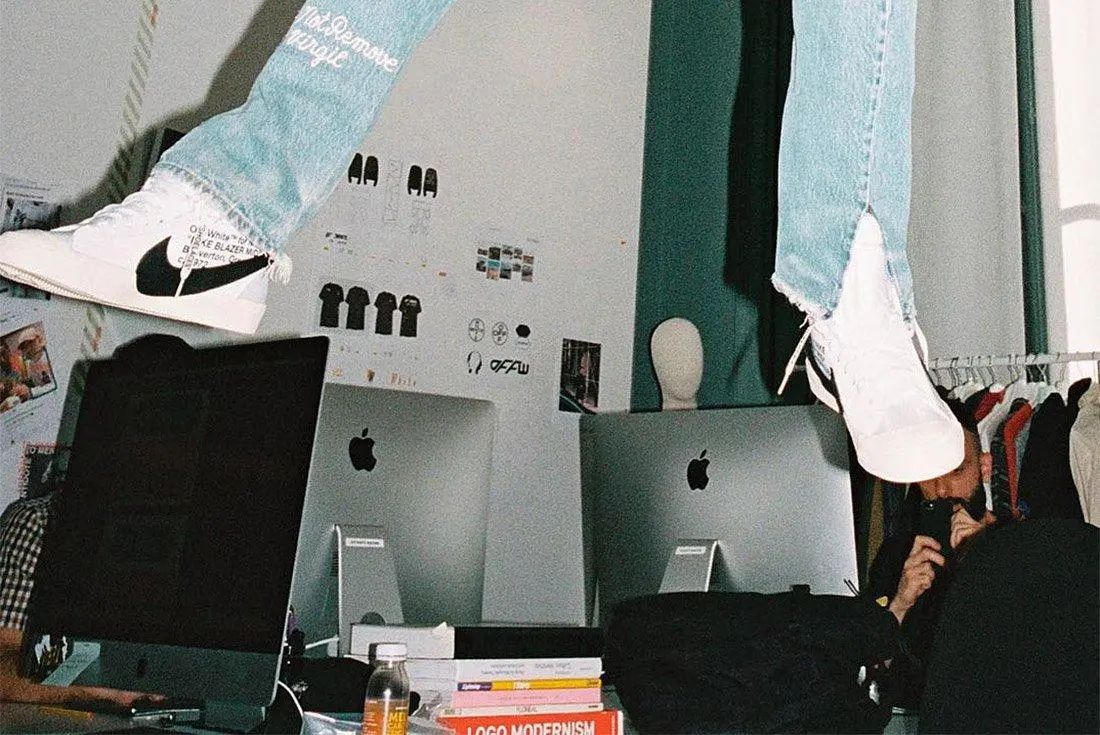

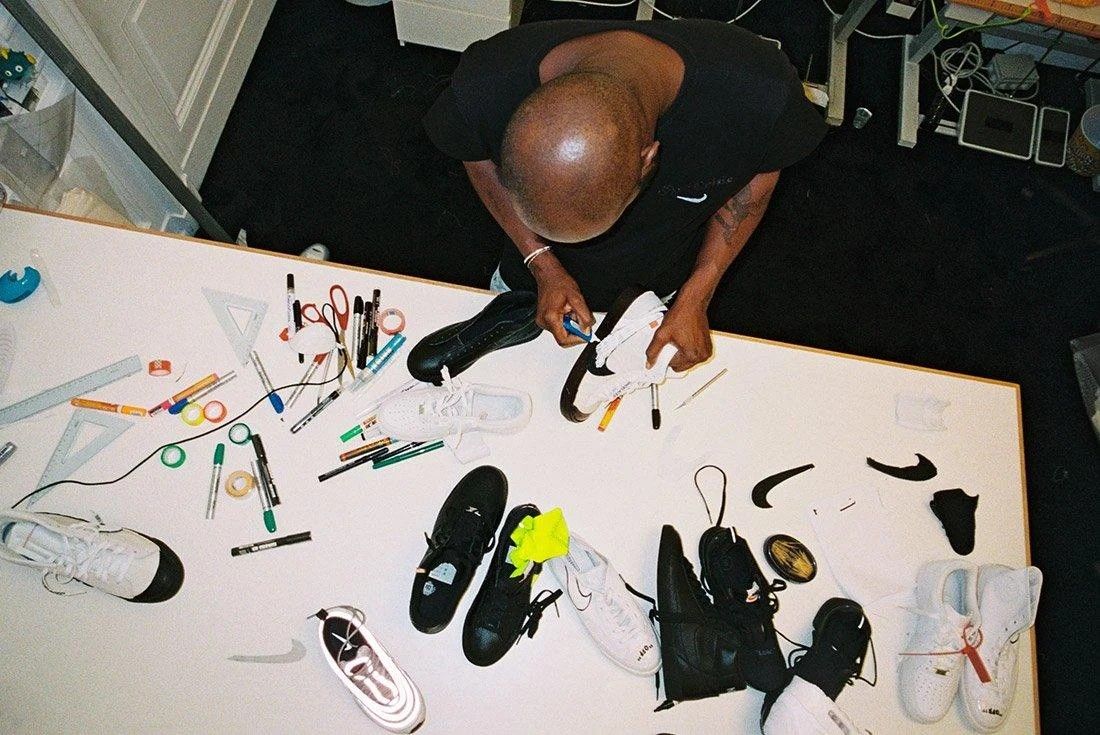

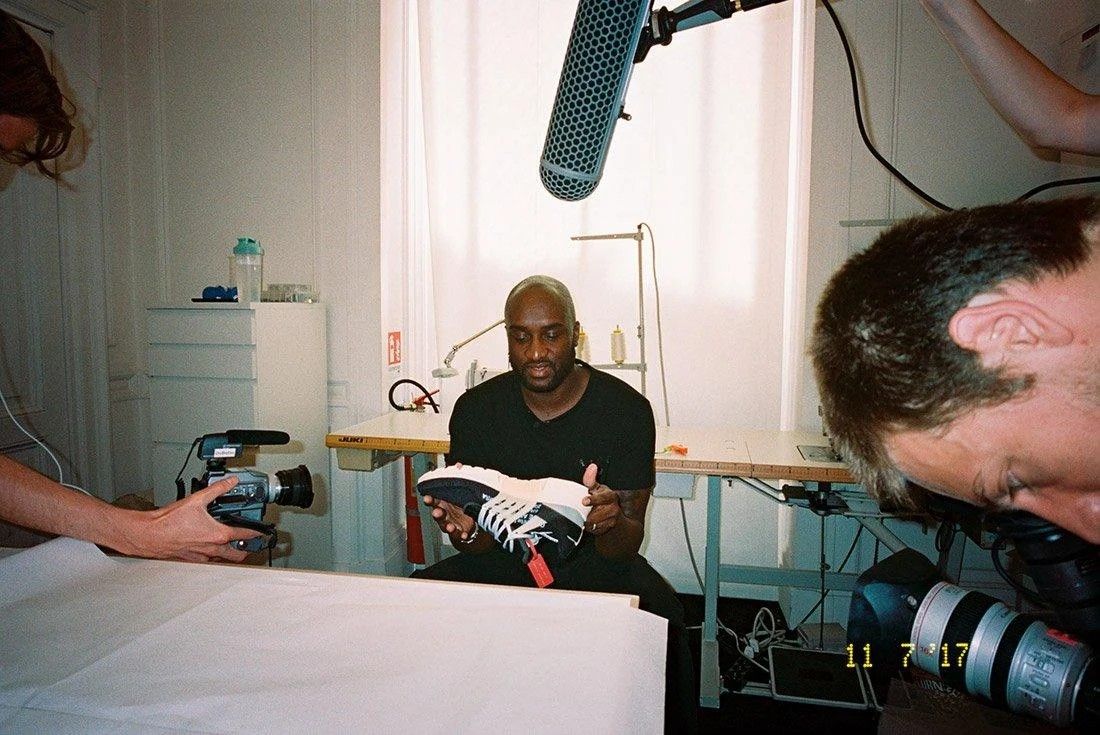

Horizontality has never been a particularly fashionable concept in fashion but the arrival of outsiders like Virgil Abloh seemed to have introduced, also in the form of criticism of the system, a new way, an idea of sharing much less centralizing. Abloh has repeatedly stated not only what his design approach was but also how he put it into practice: through a continuous dialogue with a work team that enjoyed the privilege of the word at all times and that never had to lower its eyes to its passage - an inclusive and multicultural work team. The question therefore seems to be that a creative director should not only embody the vision of the brand he deals with but should also be completely permeable to the social instances that surround him becoming, to all intents and purposes, a filter between the inside and the outside in a perspective that perhaps is not even horizontal but multidimensional and that transforms this figure into a giant magnet attached to a structure that takes charge of find a synthesis between the world as it is and the world as it should be.

Abloh has definitely left the path unfinished. By a strange case of fate a friend has just pointed out to me how much in the final release of the Vuitton fashion show in Miami of the entire Virgil work group only two were African Americans. This is not only the clear sign of the interruption of a reconstruction process but also a very strong metaphor of how the entire fashion world is going through an epochal change and is in the middle of the ford, with thrusts in the opposite directions of which the outcome is not yet understood. If the process were ever brought to completion, that is, if the creative director was at the same time the one who indicates the route and who observes the reverses of time, who looks inside and who looks outside, it would arise, in the end, a problem perhaps unsolvable but with which sooner or later fashion will have to deal with.

You can build non-elite and horizontal work teams and you can find a solid connection with the real world through an ethical approach but there will come a time when you will have to answer the question of why a sneaker costs 800 euros and a cotton sweatshirt 600. To date, no one has been able to answer this question, not even Virgil Abloh. Yet at the end of this total upheaval in progress there can be nothing but the rejection of these desperate and meaningless dynamics of growth and consequently a profound work not only on horizontality and inclusion but on the delicate point of balance between ethics and gain.