The fashion in Italian cinepanettoni movies What the longest comedy film saga tells about Italian culture

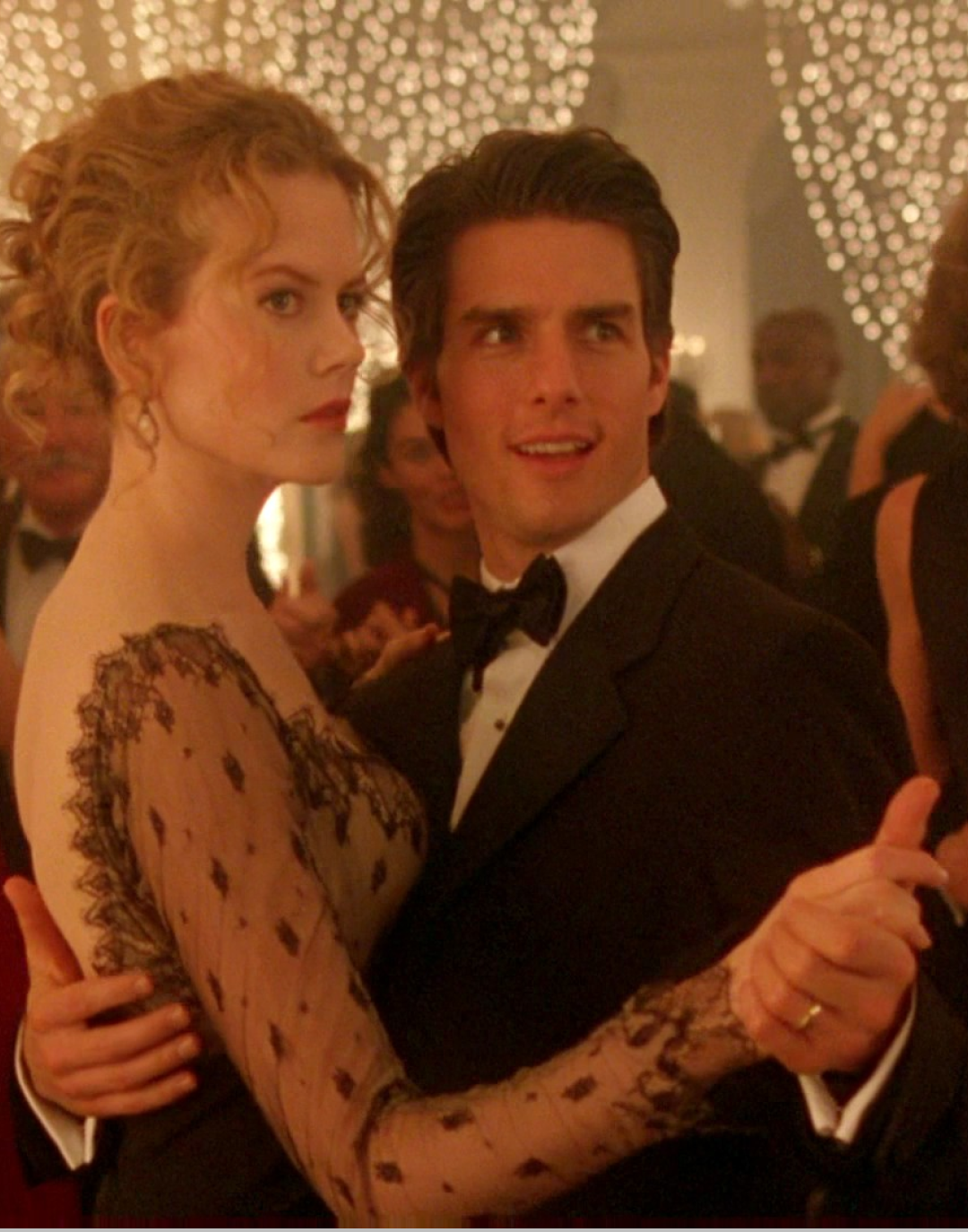

That of the white week is a myth for Italian society – a myth that speaks not only of athletics or tourism, but also and above all of social aspirations. Precisely the social aspirationality of the white week, especially those of Cortina or Courmayeur, has become the thematic core of the cinematographic trend of cinepanettoni, a series of films that went on for 35 years, which began with Vacanze di Natale '83 and ended indicatively with Vacanze di Natale a Cortina in 2011. Beyond the qualitative discourse, the public success of these films has largely been based on their ability to interpret the aspirations of the Italian middle class. This aspirationality is not only resolved in the mere destination of the trip, but in an entire lifestyle that passes through restaurants, luxury hotels, SPAs and also through the language of fashion. A fashion that, however, is not avant-garde but reassuring and bourgeois. In almost every film in the series, in fact, there is a scene filmed in a luxury boutique and, in general, all these films represent a fairly faithful picture of how the middle class imagined their own economic well-being. Today, that imagery seems perhaps a bit excessive (think, for example, of the set of twenty suitcases all by Fendi that appears in various scenes of Merry Christmas, with a cost largely unfeasible for a non-millionaire family) but it is able to create a relationship with the aspirations of the public itself and to return a faithful picture of the mainstream fashion of its time.

This relationship between cinema and contemporary pop culture emerges above all in the first film, Vacanze di Natale '83, in which the "young" Jerry Calà and Christian De Sica wear mutton coats and shimmering down jackets, both signs of the nascent culture of paninari, while the Milanese socialite Guido Nicheli, who lives in Via della Spiga, shows up in the hotel covered in fur. A whole series of very 80s and today very dated looks that however fits well into the discourse on the dynamics between appearances and social classes that is articulated during the film and that continues in the following culminating, in the final film of the series, with the appearance of Emanuele Filiberto di Savoia and that (inexplicable) of the designer Renato Balestra. But in the course of the other films of the saga the relationship between Italians and fashion is constantly reconfirmed. Some examples in no particular order: in Merry Christmas, Massimo Boldi's character goes around Amsterdam with a Burberry scarf and the comic duo Fichi d'India find themselves in the middle of a Just Cavalli fashion show; in Natale a Beverly Hills there is a whole scene shot in a boutique of Ermenegildo Zegna and just before during the film De Sica drives away a dog saying: «Are you pissing on my Pradas?» anche se la line più iconica è quella del primo film del 1983, nel monologo del giovane De Sica sorpreso a letto con un altro uomo che dice al padre scandalizzato: «You have been cheated by your own well-being [...]. And then, doesn't mom play at the rowing club and do shopping at Versace? Don't you put the watch on your wrist like Gianni Agnelli?»

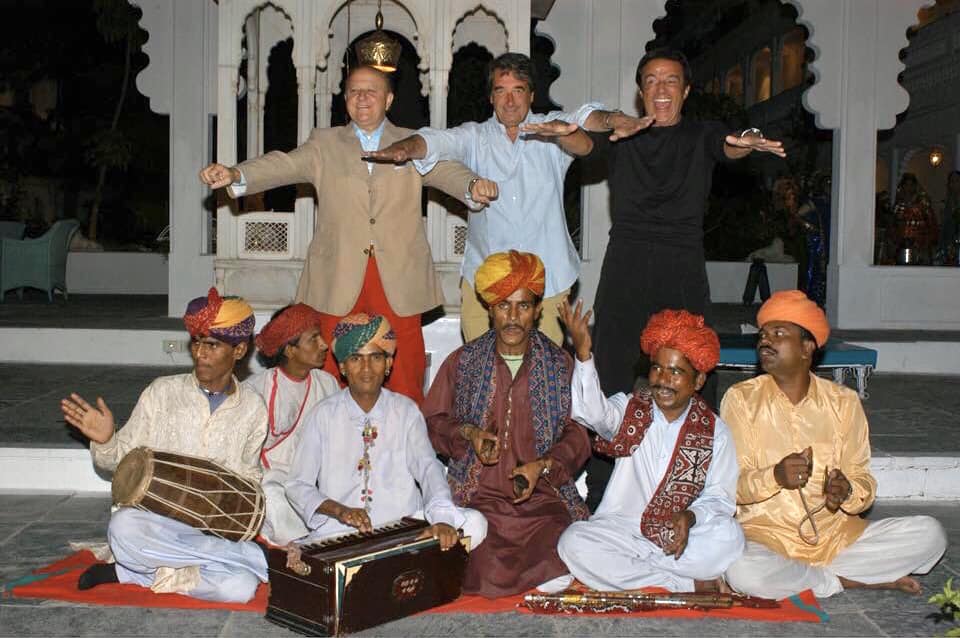

All moments (especially the last mentioned) that draw a clear parallel between fashion and social aspiration of the middle class – criticizing on the one hand the contradictions of moral values of the Italian provincial parvenu, but also highlighting the deep fascination that Italy feels towards the social redemption promised by fashion. With time and the stabilization of society, this aspirationality has become more implicit: we have gone from minks and furs to men's suits and coats; with frequent appearances of a more youthful and contemporary fashion in films such as Natale sul Nilo, where Maria de Filippi appears in an ensemble of trousers and white tank top decorated with a butterfly that seems halfway between Matthew Williams and Blumarine; or in Natale in India, where the rapper played by Enzo Salvi becomes the representative of that wave of youthful fascination towards the hip-hop of Eminem and 50 Cent that, a generation later, would become the streetwear of A$AP Rocky and Drake. Today cinepanettoni no longer exist and the aspirationality of fashion is communicated through the most immediate feeds of social networks – yet that long line of films remains as the document of a pivotal period of Italian pop culture in which society and fashion as we know them today began to develop and take on their form.