Zara and the fast-fashion that plays luxury Suspended between two worlds, the fast-fashion giant is a brand that doesn't want to be one

After a 2020 to forget, the fast-fashion sector has reappeared in the new year more determined than ever to gain again that slice of the market lost between pandemic and closed stores. Among them all, of course, is the Inditex group, parent company of Zara, Bershka, Massimo Dutti, Pull&Bear and Stradivarius, ready to close 2021 in clear growth with a revenue of about 12 billion in the first half of the year and an increase in sales of 49% over the previous year. It's no secret that the Spanish group's turnover is driven by Zara, which over time has become the leading player in the fast-fashion sector thanks to its sectoral balancing act, capable of making the company live in limbo between low-cost fashion and the promise of a world of values in stark contrast to that of its competitors.

At the heart of Zara's success is first of all the ability to be a mirror of the trends of the moment, no longer bringing to the store knock-offs of looks seen a few weeks earlier during fashion weeks, but instead looking through the trends of TikTok and Instagram in an attempt to intercept the tastes and desires of users. The latest example in chronological order is the pleated collection of Zara, revised and corrected version of the Homme Plissé by Issey Miyake, which has become a fixed presence in fit-pics or in the "get dressed with me" that clog the feeds of social networks. What for many might seem to be just a disrespect to the Japanese designer, is actually only the practice of a business model that has its main strength in speed. A concept that starts from the choice of producing more than 50% of the products in countries close to Spain (Portugal, Turkey and Morocco) to reduce delivery times, up to that of creating collections in small quantities, reducing inventory and giving a continuous idea of what's new inside its stores. In this perfectly functioning machine, capable of creating and producing a collection in five weeks, the leading role is that of communication, where Zara has managed to distance itself from H&M or Uniqlo, creating a middle ground between two distinct levels. From the website to the in-store display, the brand has gradually absorbed the language of luxury fashion, making it its own until it has become the paradox of a brand that doesn't want to be.

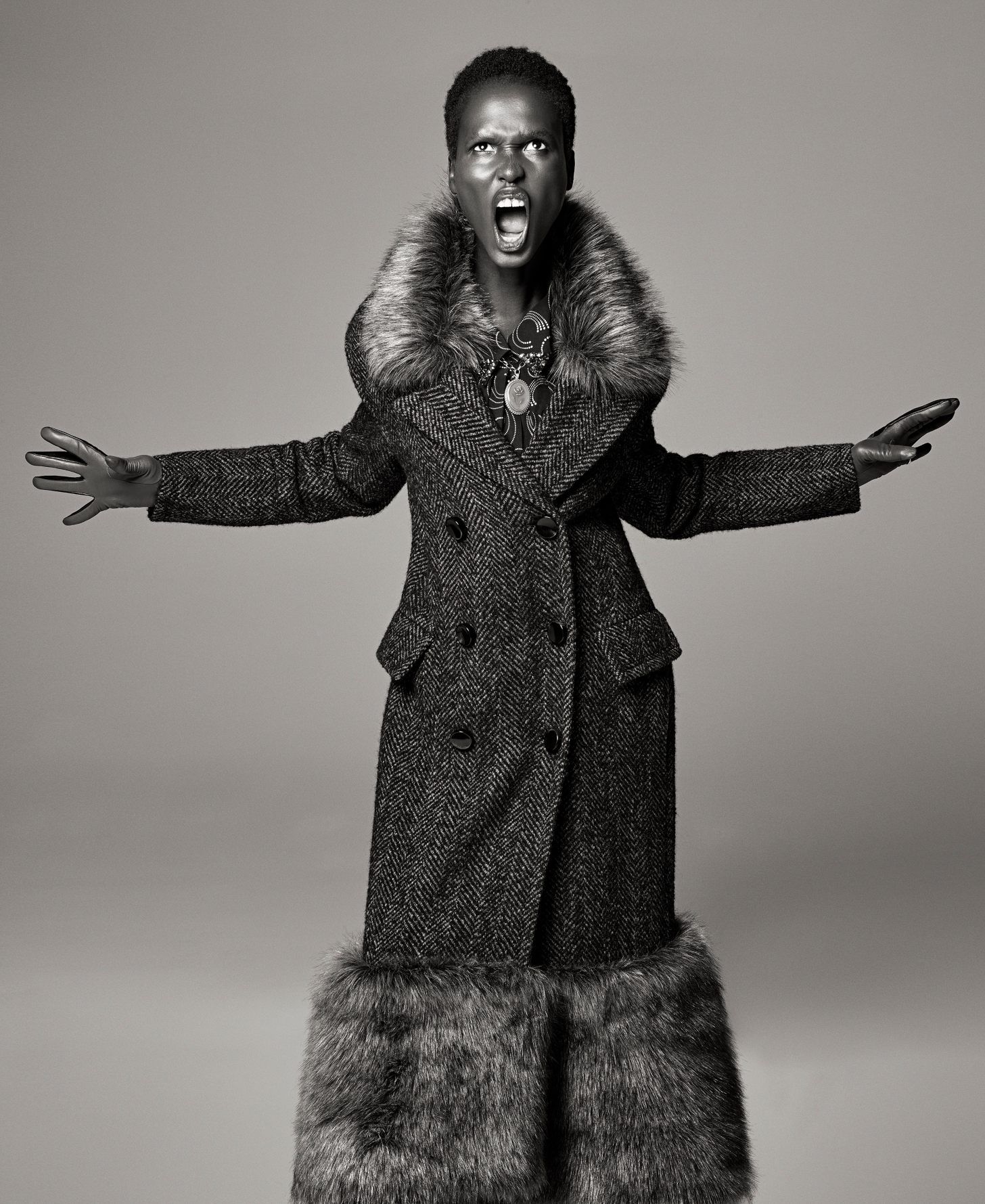

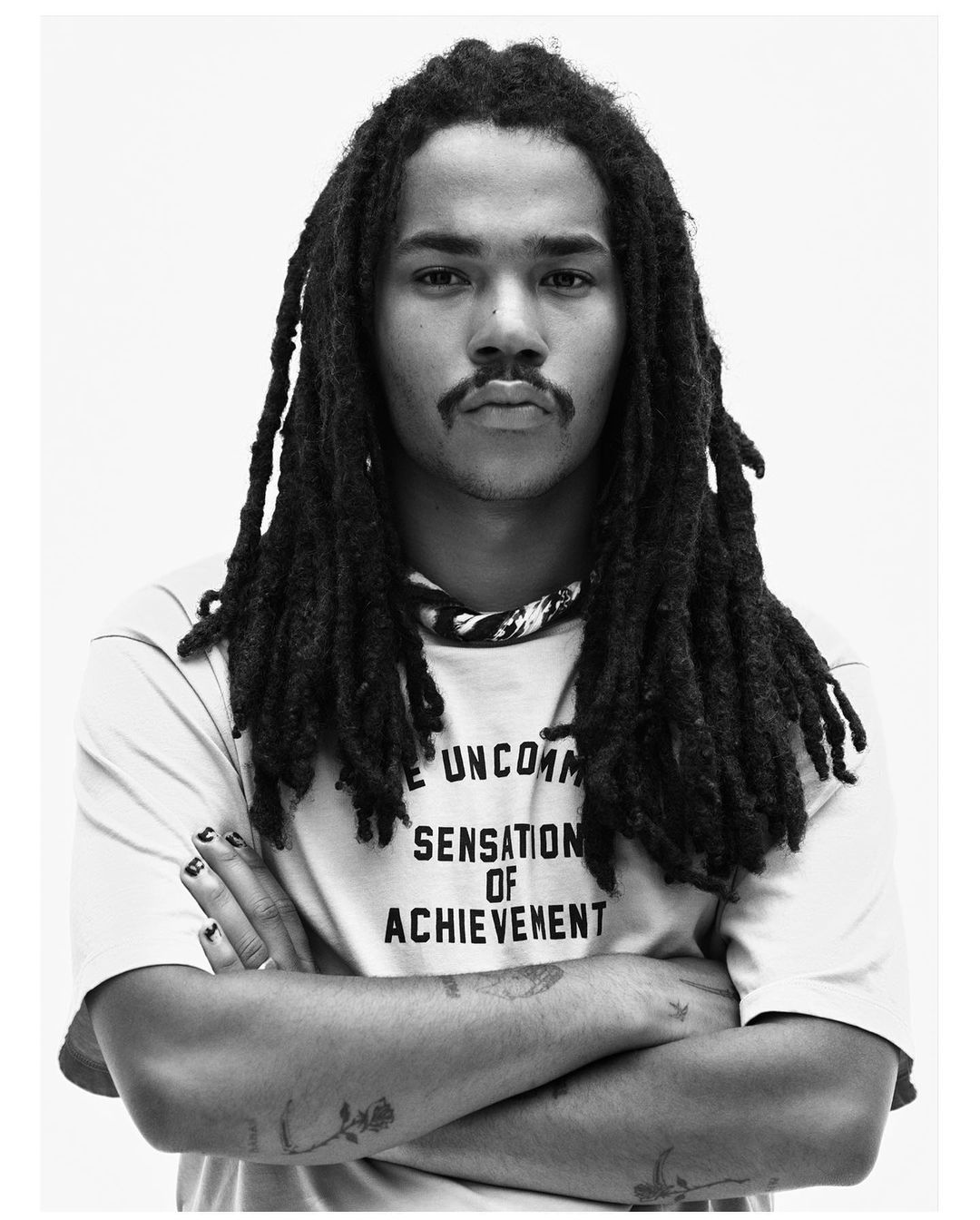

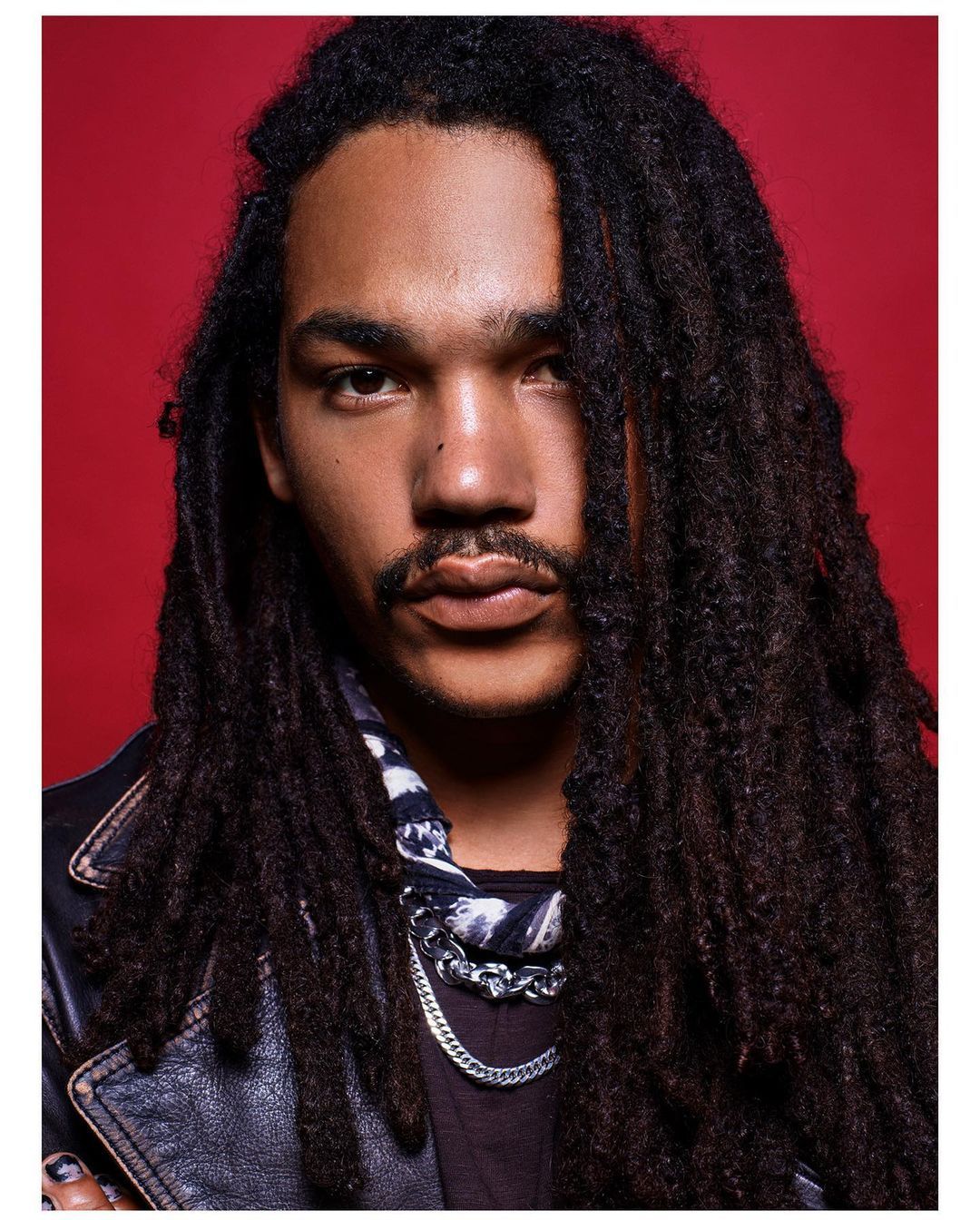

With twenty collections a year, Zara seems to be closer to the rhythms of a true fashion brand rather than the seasonality of fast-fashion, anchored in many ways to the idea of a fashion that is sharply divided and accessible from a single doorway. As Ana Andjelic wrote in her newsletter, in its growth Zara has decided to adopt a Galaxy model, where multiple realities are held together by the history and weight of the brand itself, capable of keeping consistent the sub-brands that gravitate to the microcosm. Some examples in this sense are those of Ralph Lauren and Armani, while in the case of Zara are part of the same galaxy collections Origins, Studio and Athleticz together with the lines Zara Kids, Zara Home and Zara Beauty in a model whose main strength is to provide more entry points within the philosophy of the brand. A communication in which Steven Meisel photographs Marisa Berenson, Sasha Pivovarova, Chiharu Okunugi and Yumi Nu, in which Chloë Sevigny is the protagonist of a campaign of Zara Home and Charlotte Gainsbourg has her own capsule.

In spite of everything, Zara seems to have no intention of changing its approach to fashion, continuing to represent the affordable and accessible alternative to luxury fashion, strong of its unique status in a world where Shein's advance continues unabated. Balancing between two worlds, Zara is free to tell its customers a different story from that of its competitors, avoiding in a certain sense to take on major responsibilities, thus not repeating the path taken by Cos, the brand part of the H&M group that in September paraded at London Fashion Week marking a unique precedent of its kind. So, in the era in which in theory everyone condemns fast-fashion but in practice no one does without, the giant of the Inditex group succeeds perfectly in its intent to live halfway between two worlds, free not to position itself in a precise box but certainly able to sell the best of what it has to offer and that we all love to hate.