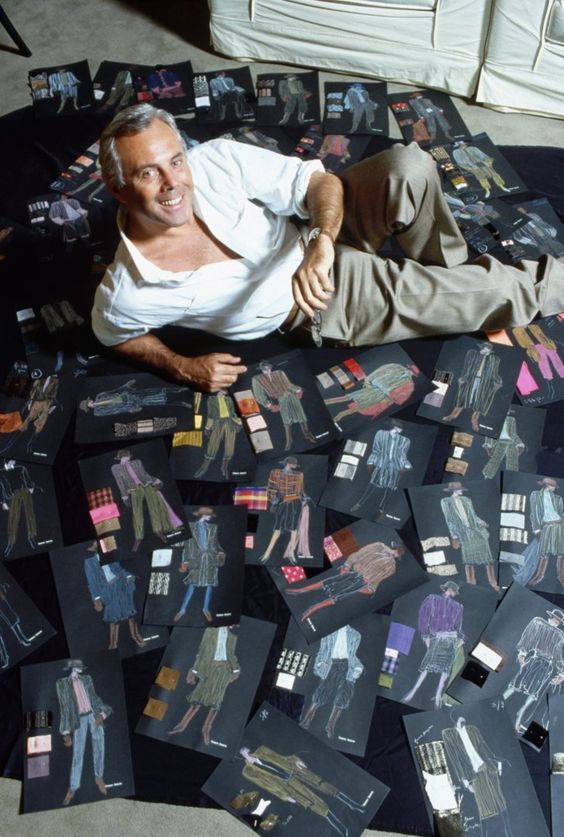

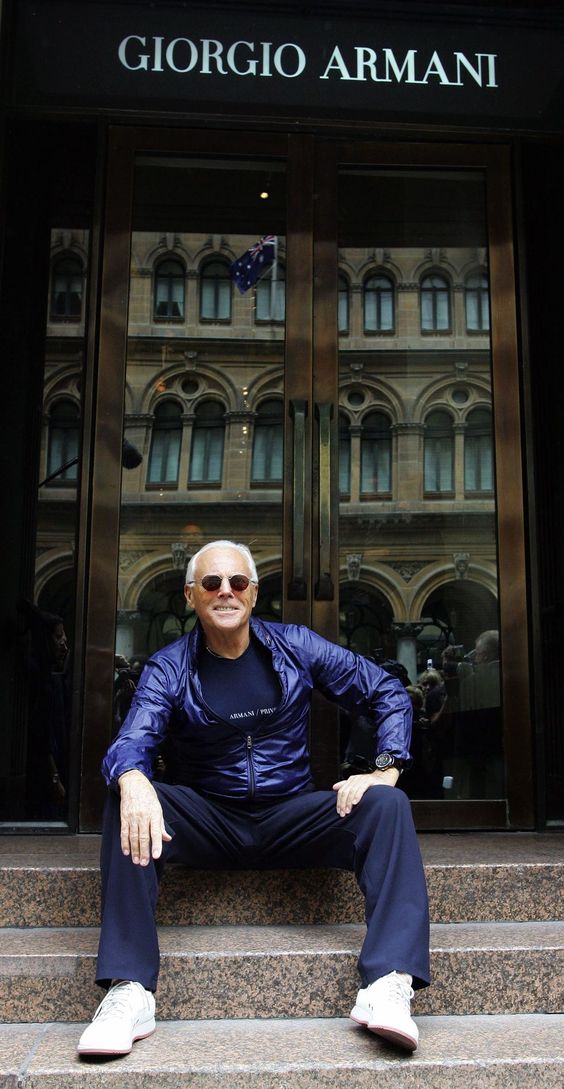

The nostalgic modernity of Emporio Armani How Armani's diffusion line rewrote the idea of luxury in the 80s

During a conference held in Florence for Confindustria in July 2024, Maria Grazia Chiuri of Dior said: «We should forget the whole idea of "democratic" fashion here in Italy. If a garment is done well, why does it have to be "democratic"?». Words that brought to mind the description of his Emporio Armani line that Giorgio Armani made at GQ in September 2023: «I imagined it as a line with which to experiment, capturing new trends and proposing a democratic fashion». In times like these, when the fashion industry tries to reach the highest possible number of customers but would do anything not to appear elitist, the question of the democratic nature of fashion has emerged with dramatic importance. On the one hand, consumers are encouraged to want new products while on the other hand, they are told every day that fast fashion is unsustainable and that therefore it is necessary to find an alternative to unbridled consumption. Recently this alternative has been vintage: from the classic markets to the digital empire of Grailed, the fashion of the past has become the surrogate to the polluting fast fashion, to the lightning-fast cycles of its trends and to its synthetic fabrics produced in the most remote sweatshops in the world. Precisely this vintage trend has brought back a brand like Emporio Armani, whose 80s and 90s garments have found a second life as a sober and versatile uniform of Millennials and Gen Z - a response to the visual aggressiveness and prefabricated hype of fashion on social media that contrasts the value of timelessness with that of coolness.

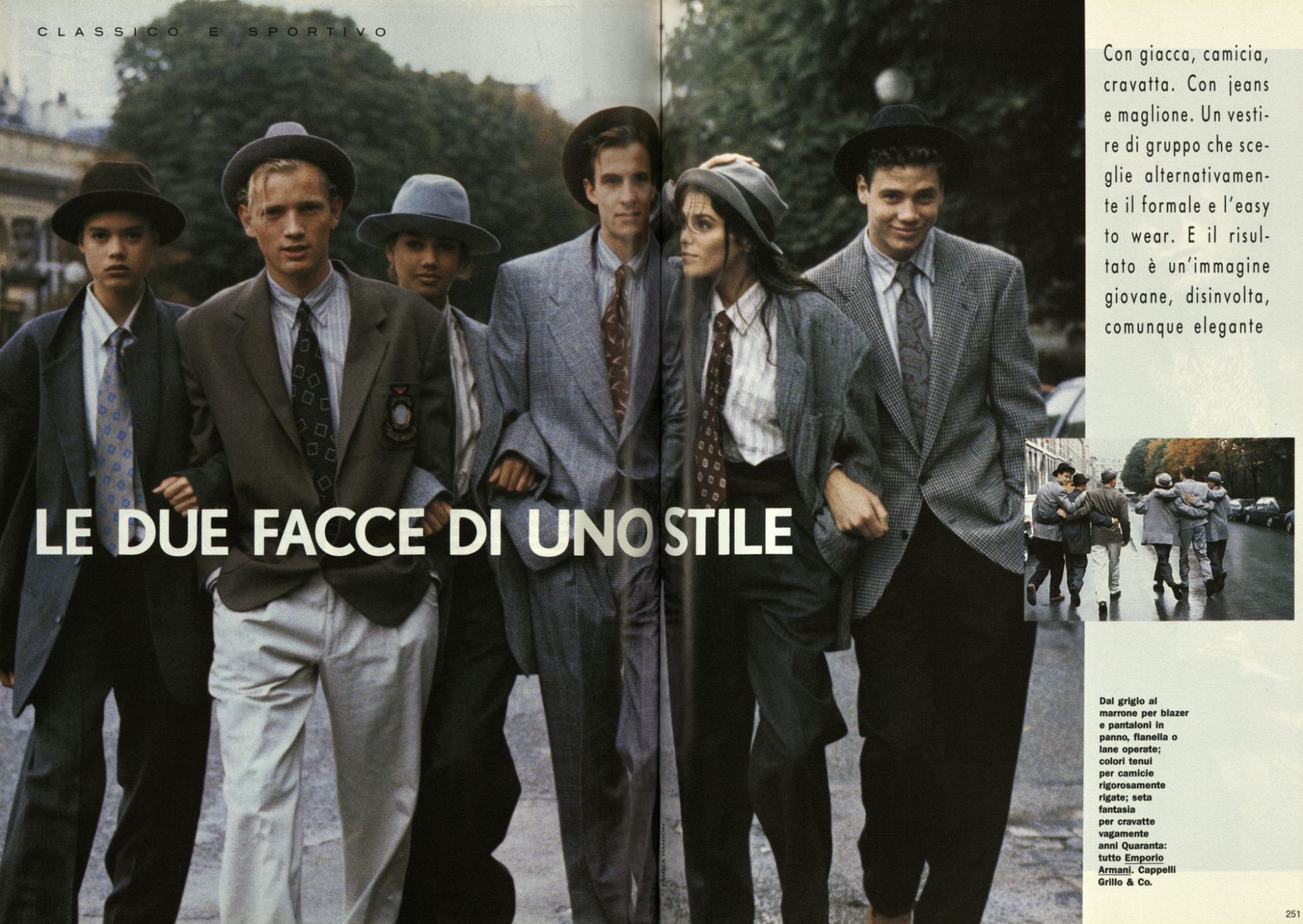

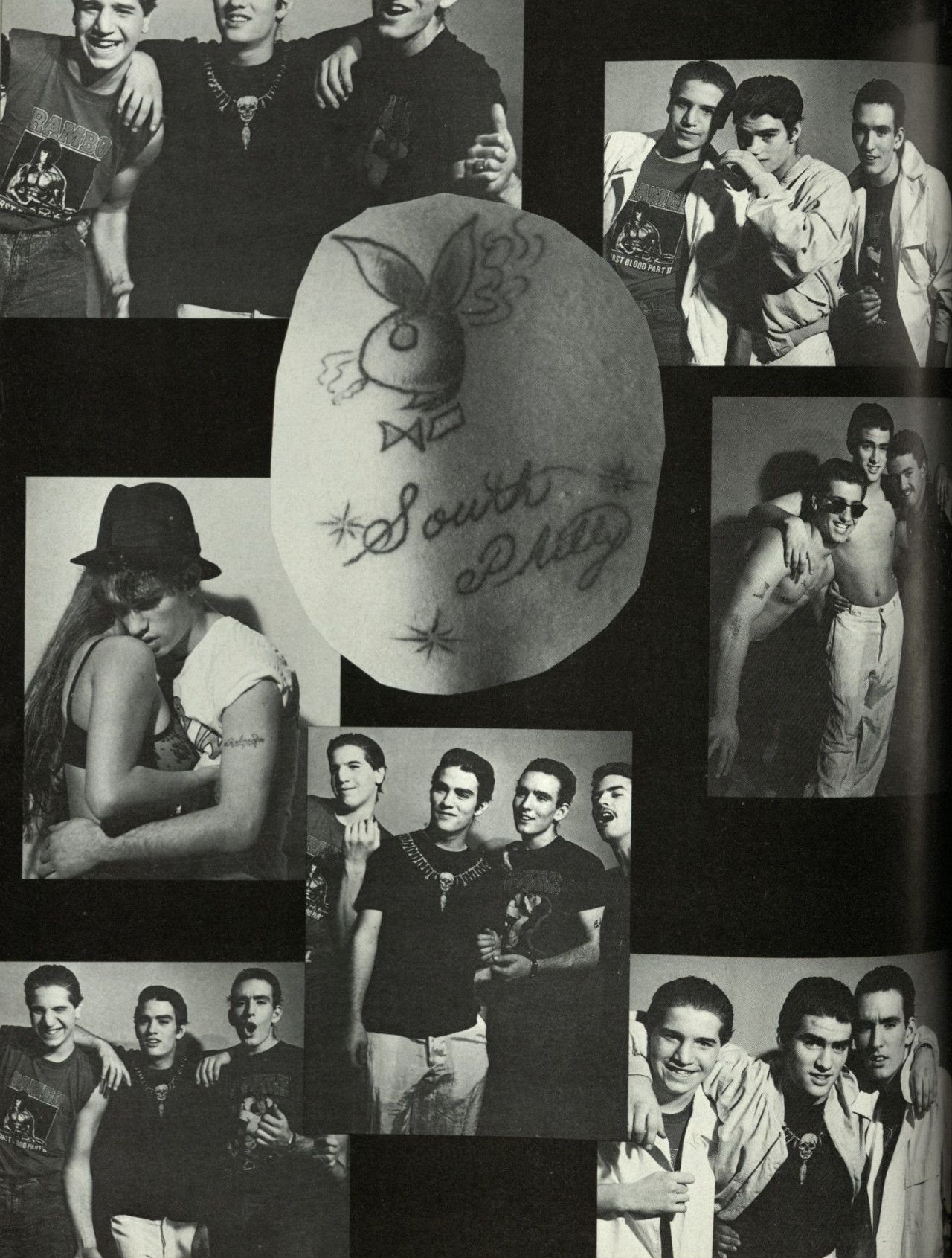

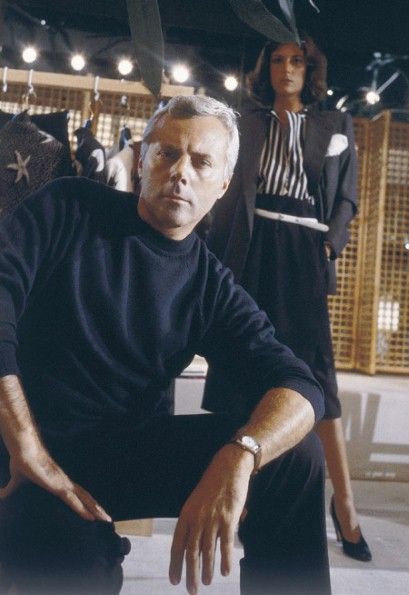

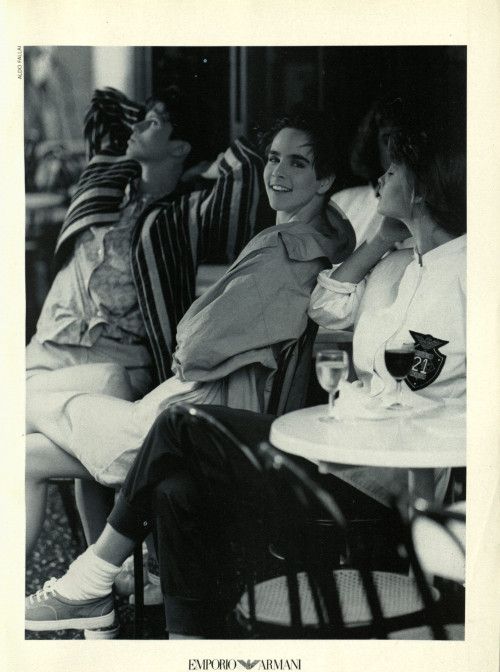

At the time of its birth, in fact, Emporio Armani meant a lot for Italian youth fashion: the first store opened in 1981 in Via Durini in Milan, a stone's throw from that San Babila that would become the cradle of paninari but above all of yuppies, the two first Italian youth subcultures. The data is very important because the yuppies represented the first generation of Italians who assigned to fashion and luxury the task of defining their identity, with a clear detachment from the rigor and monotony of a tradition made of a tailoring that was often reduced to monotonous bourgeois uniform.

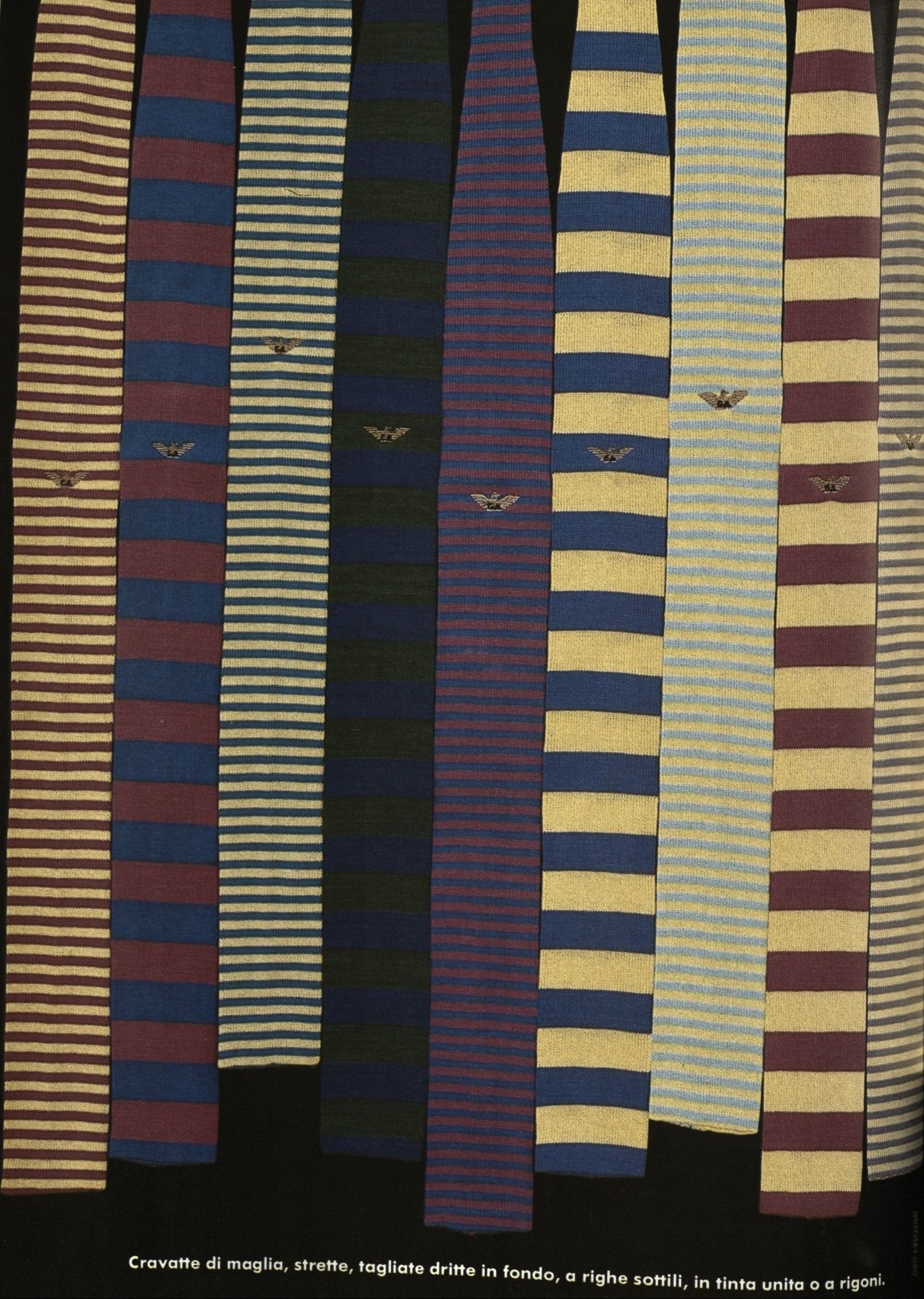

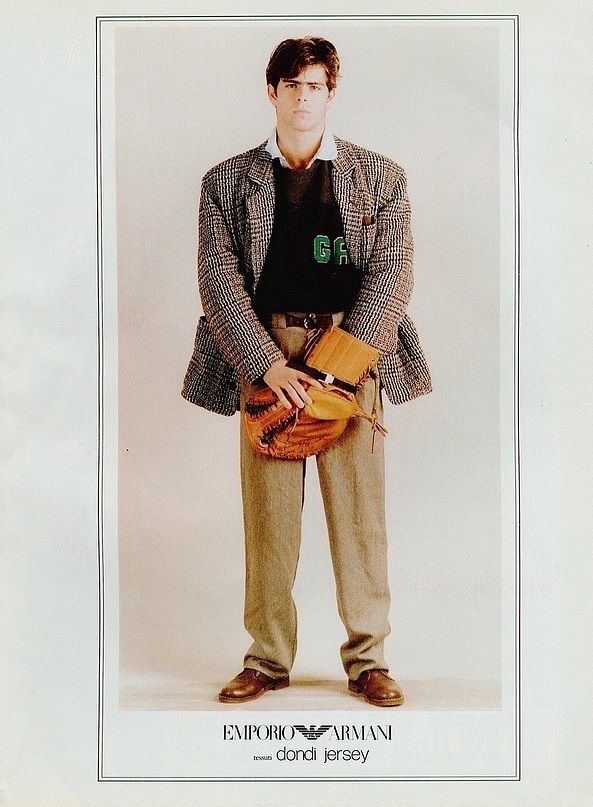

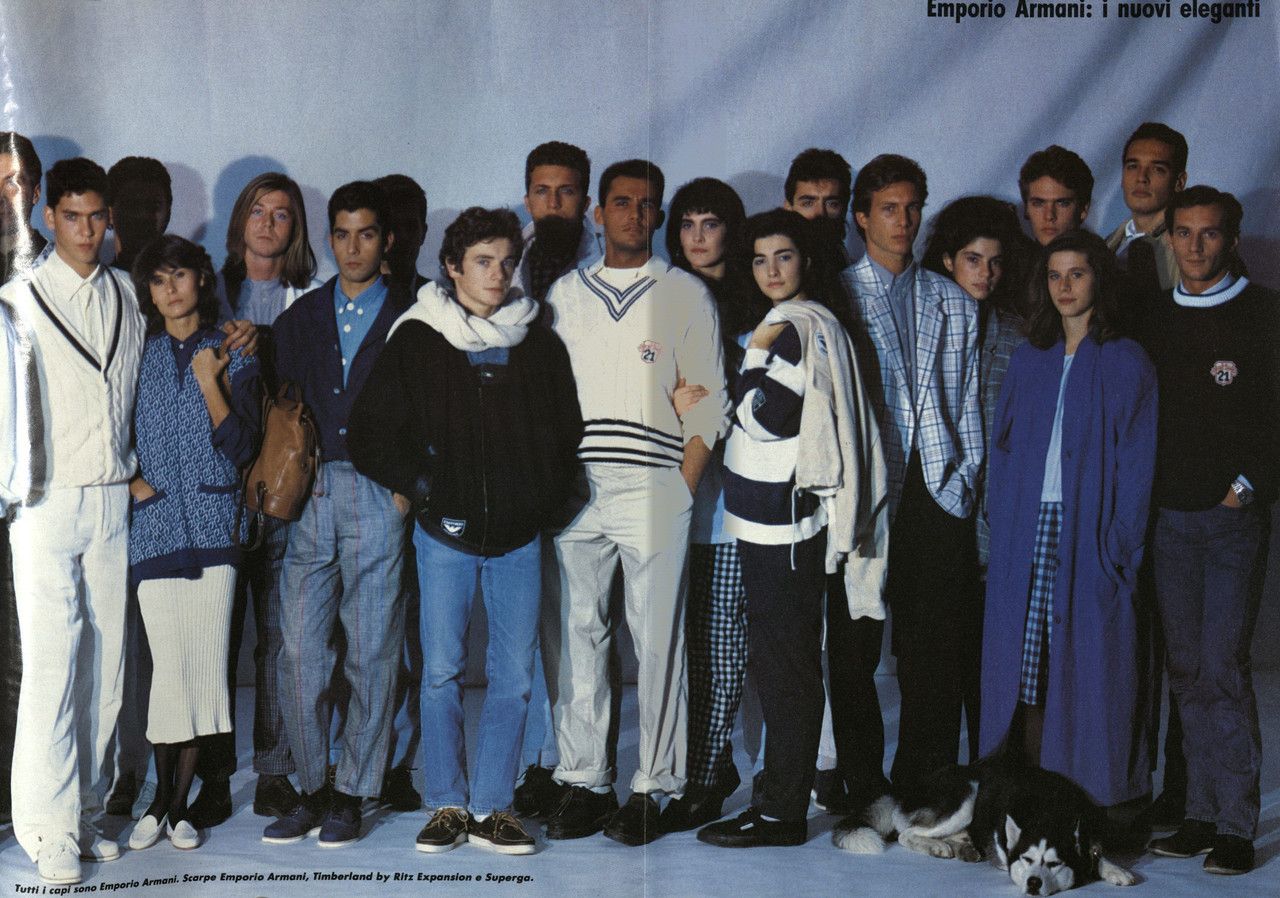

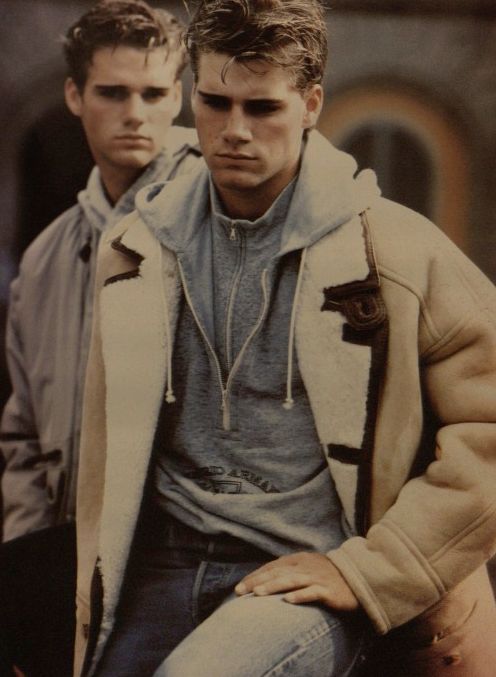

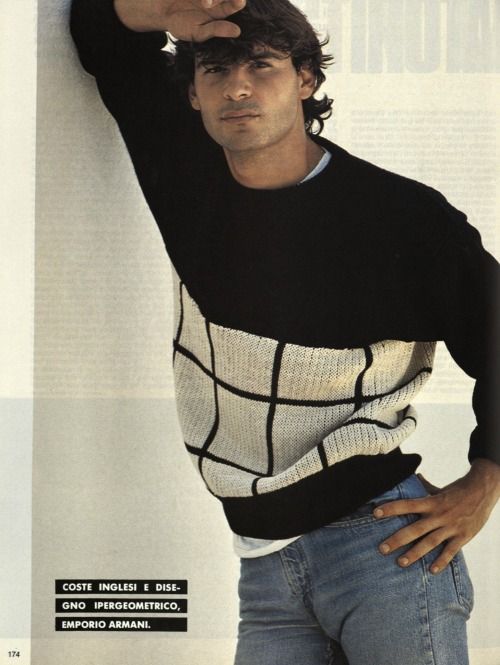

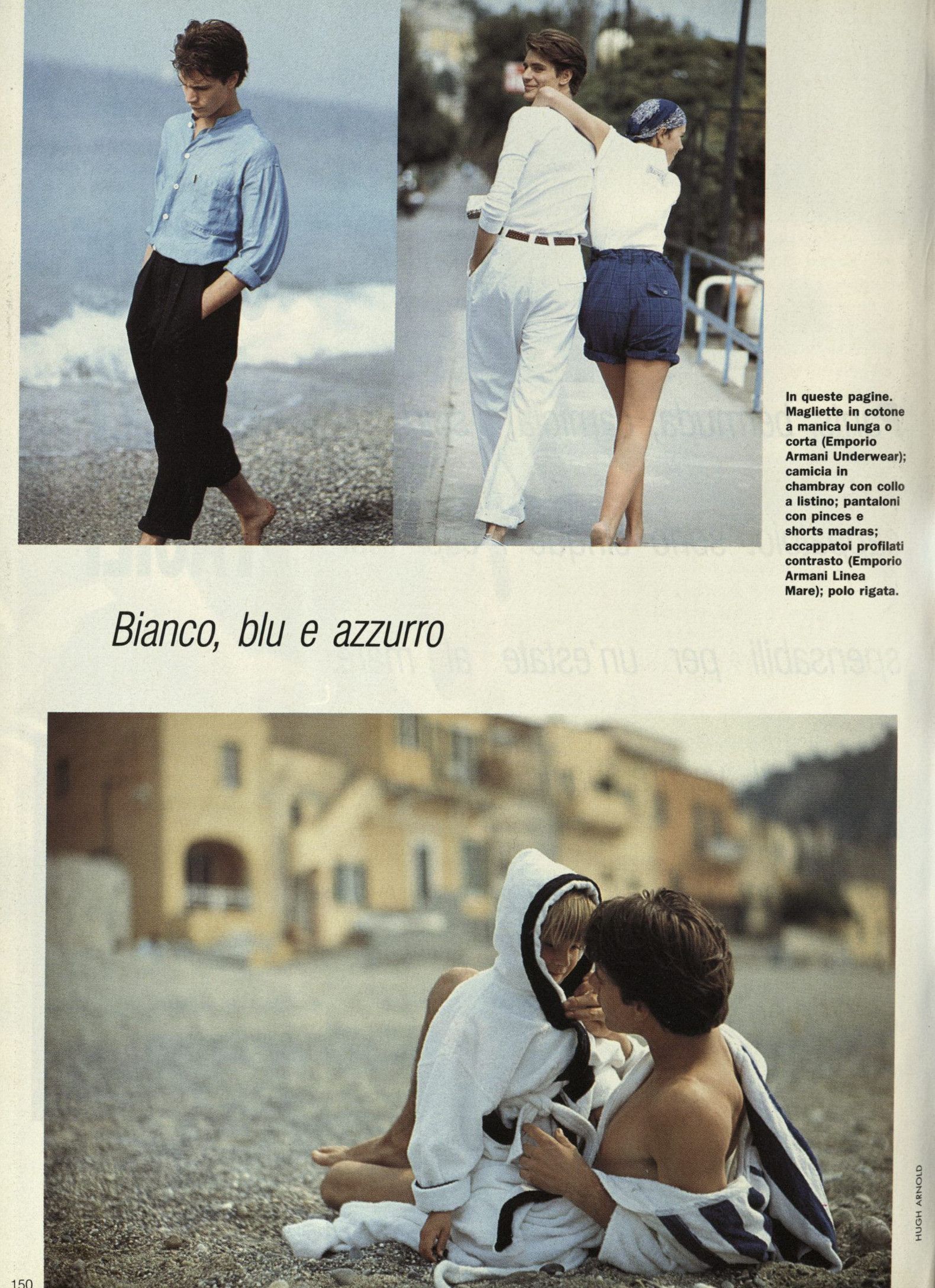

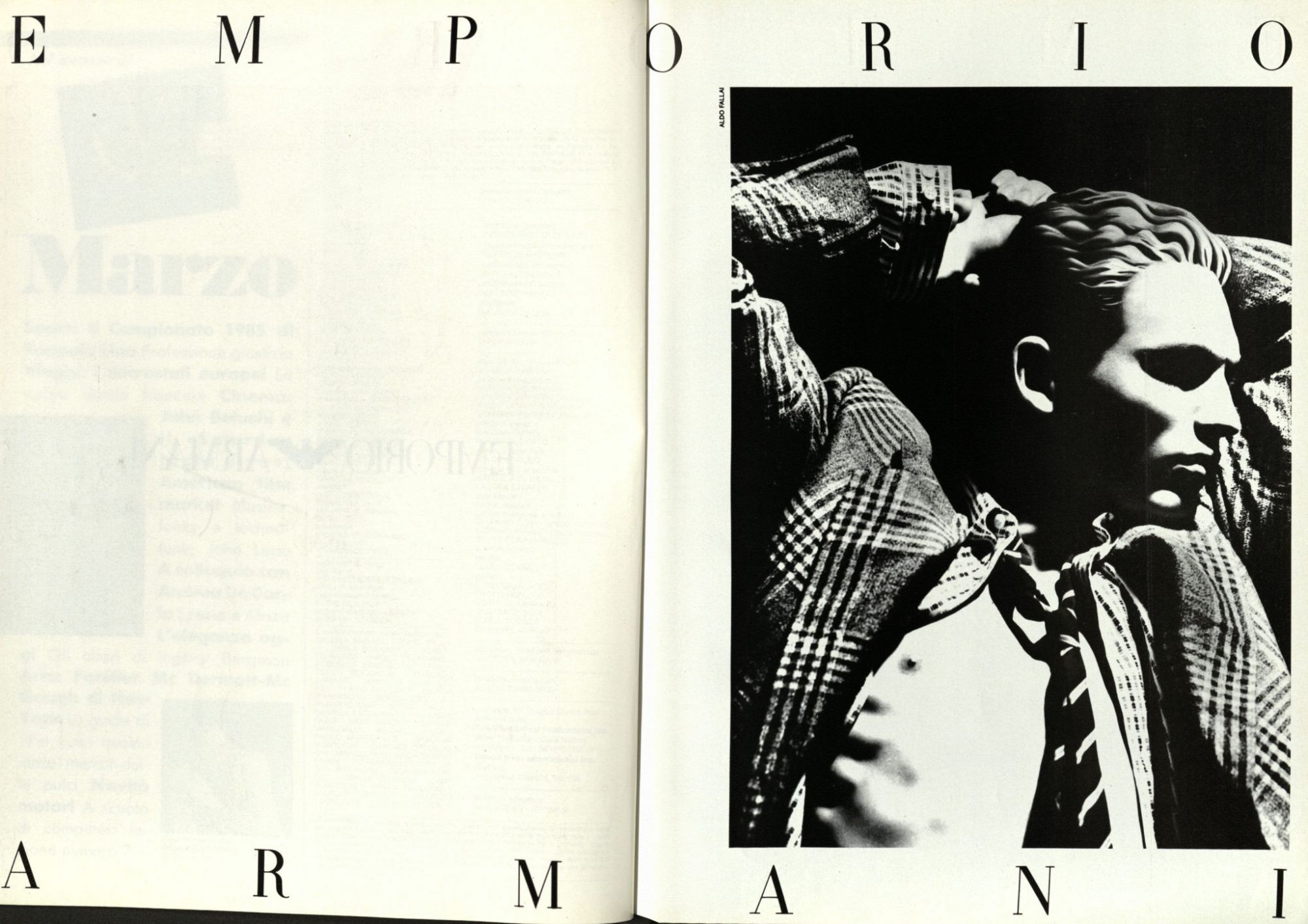

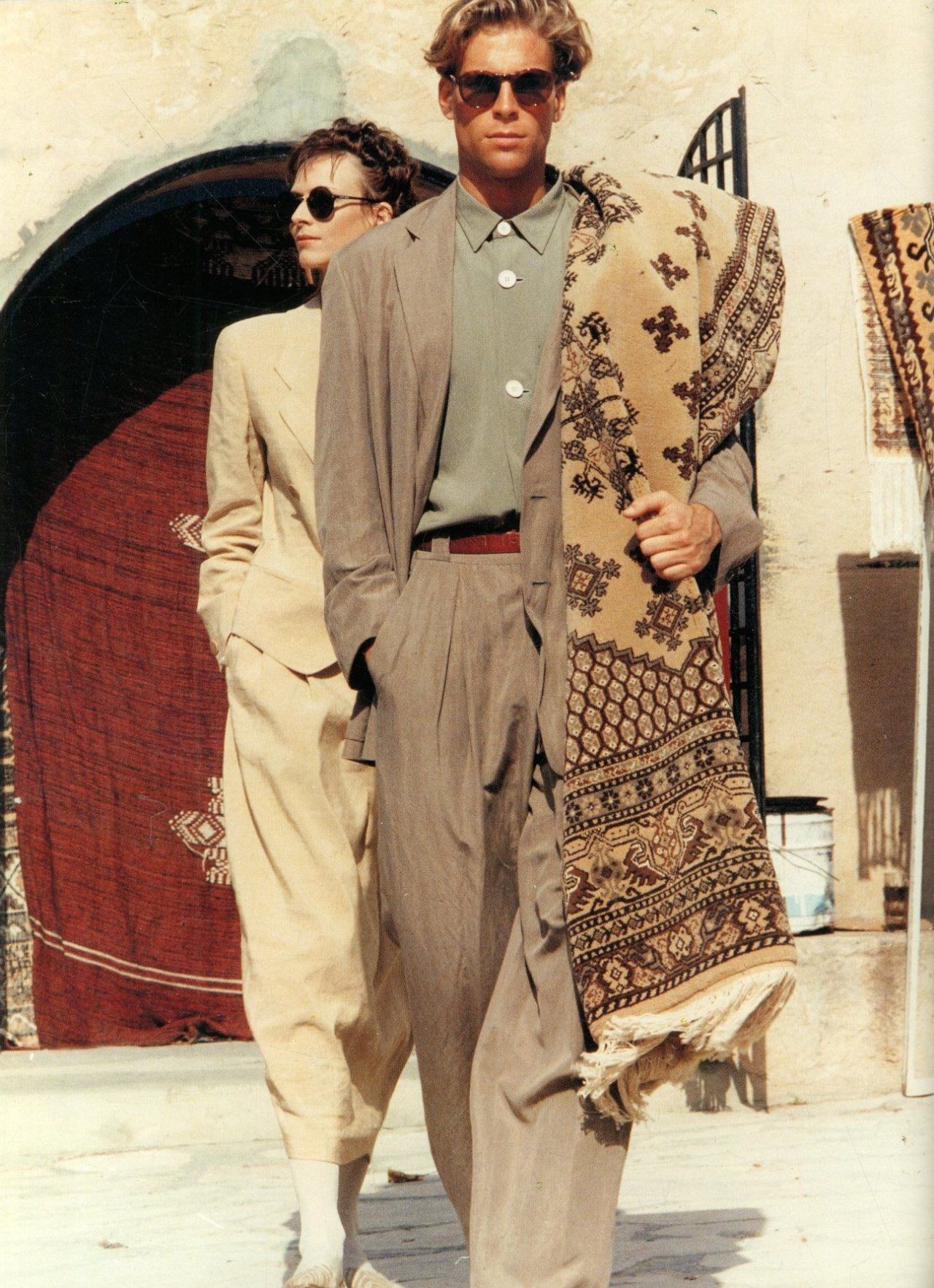

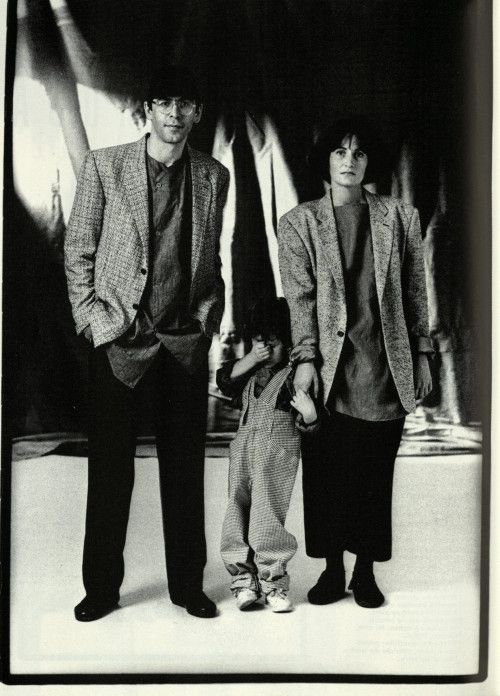

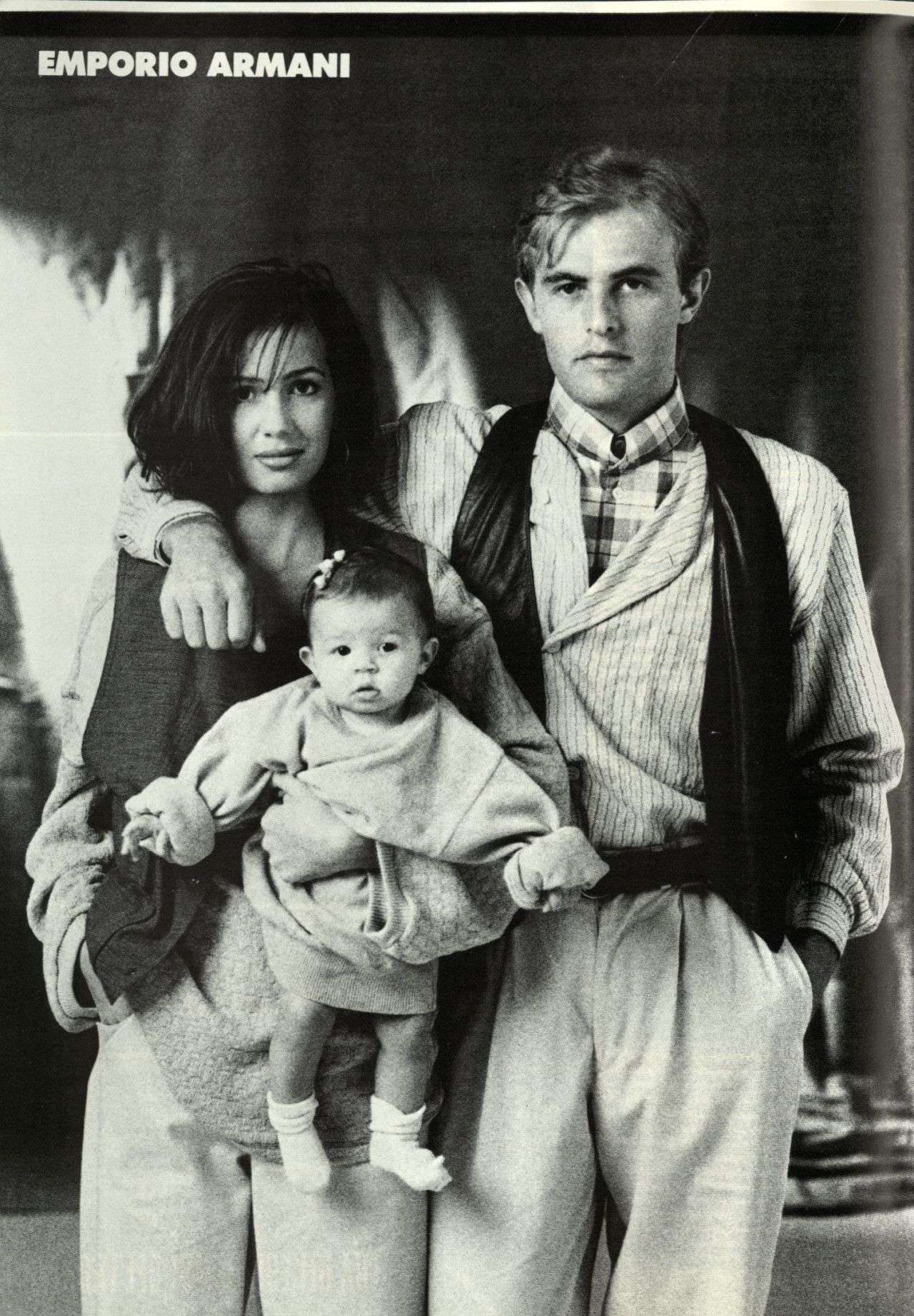

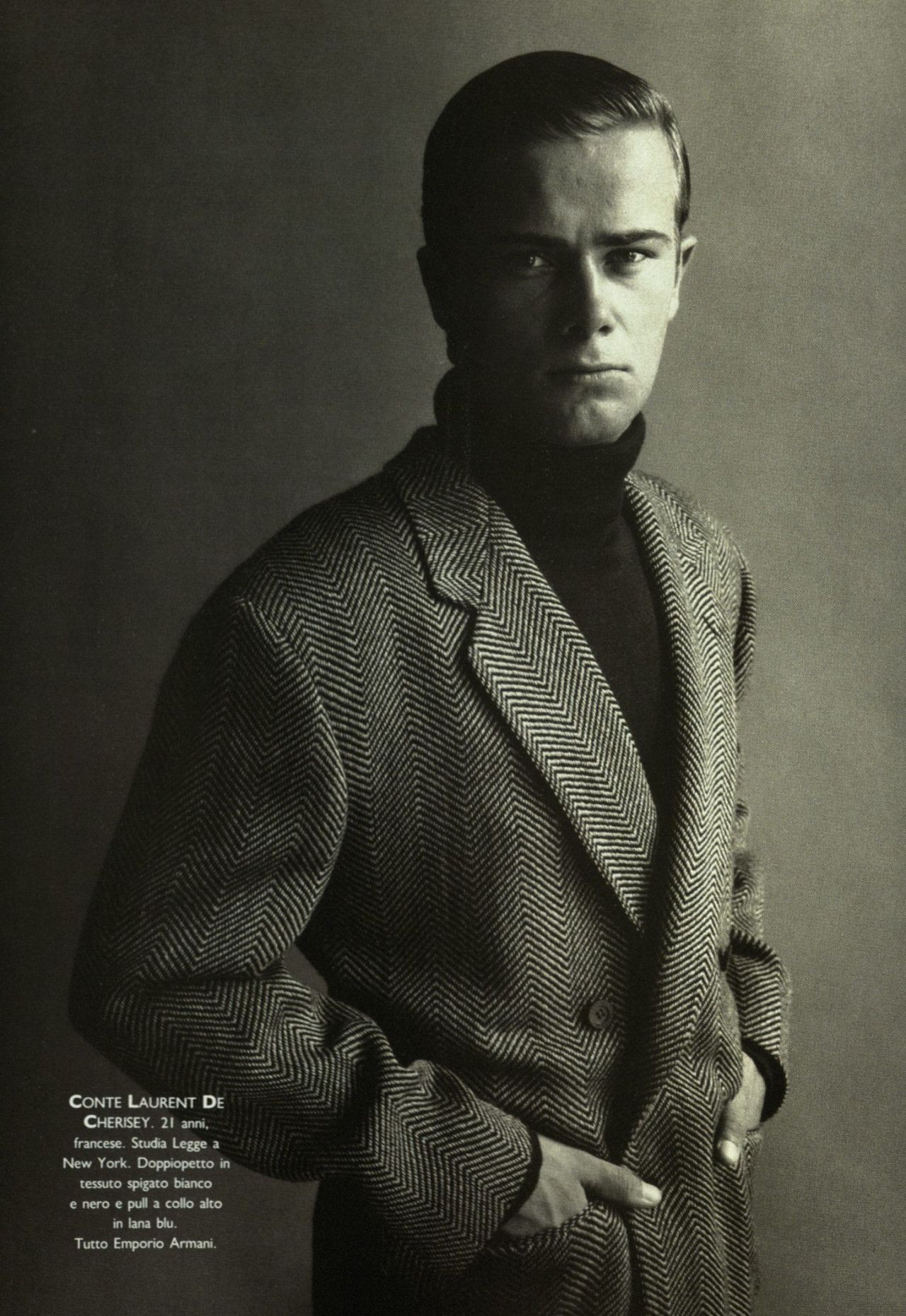

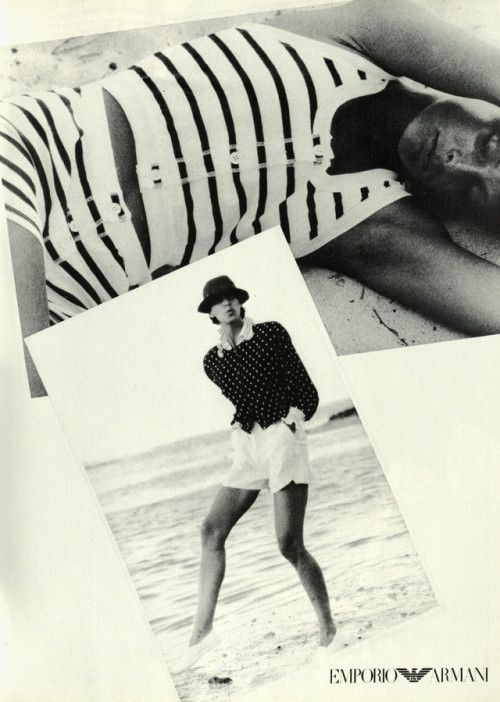

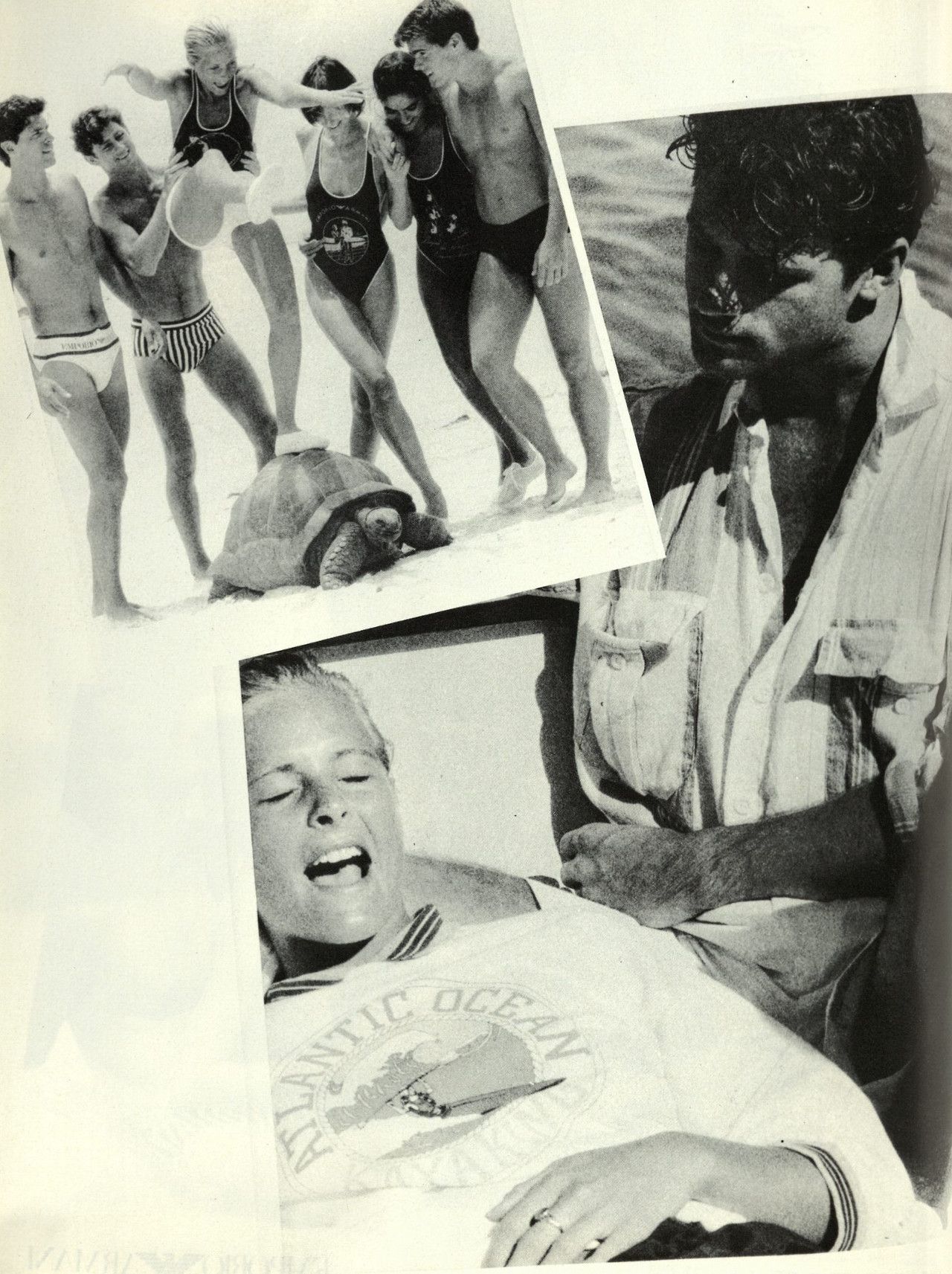

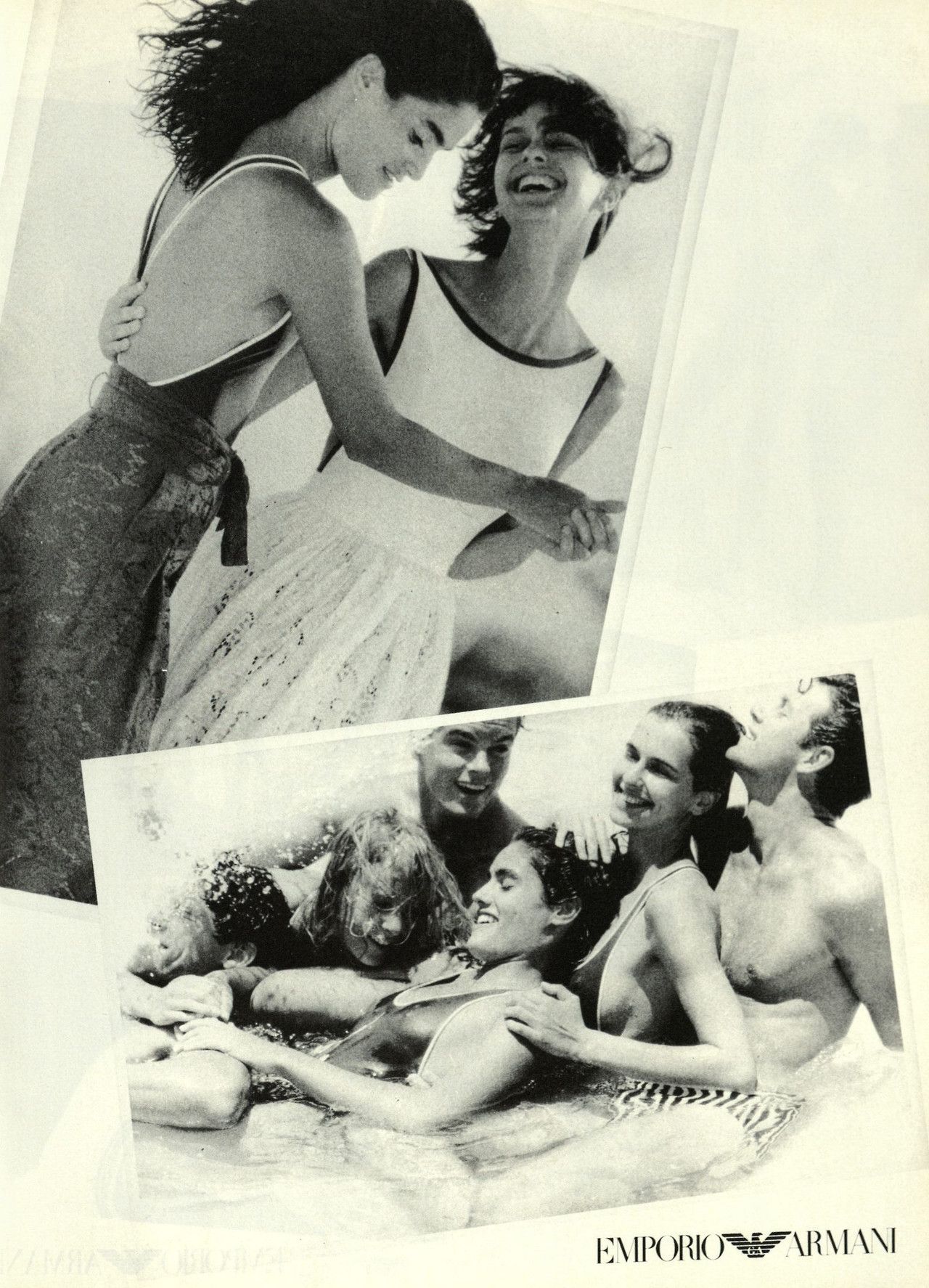

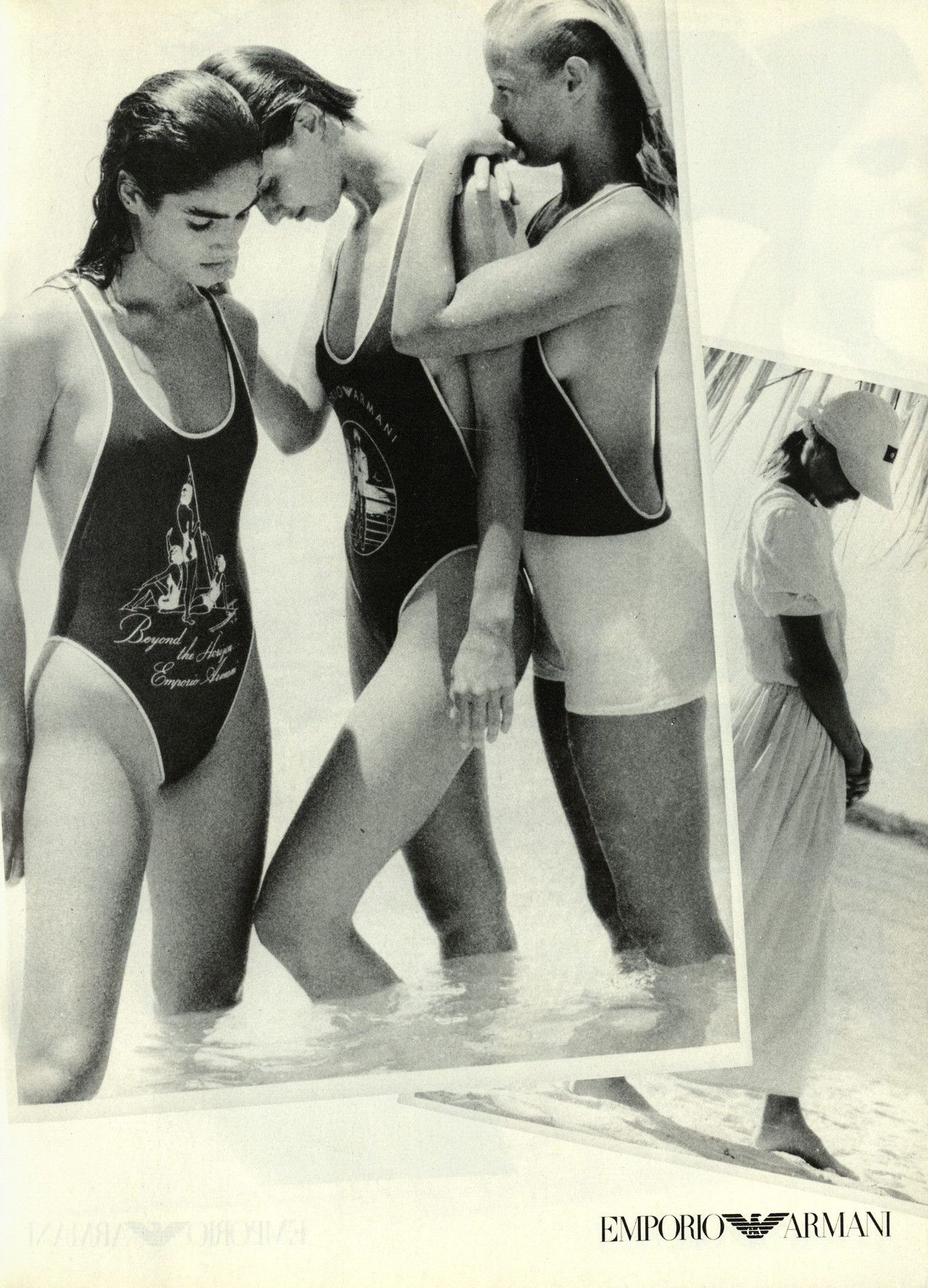

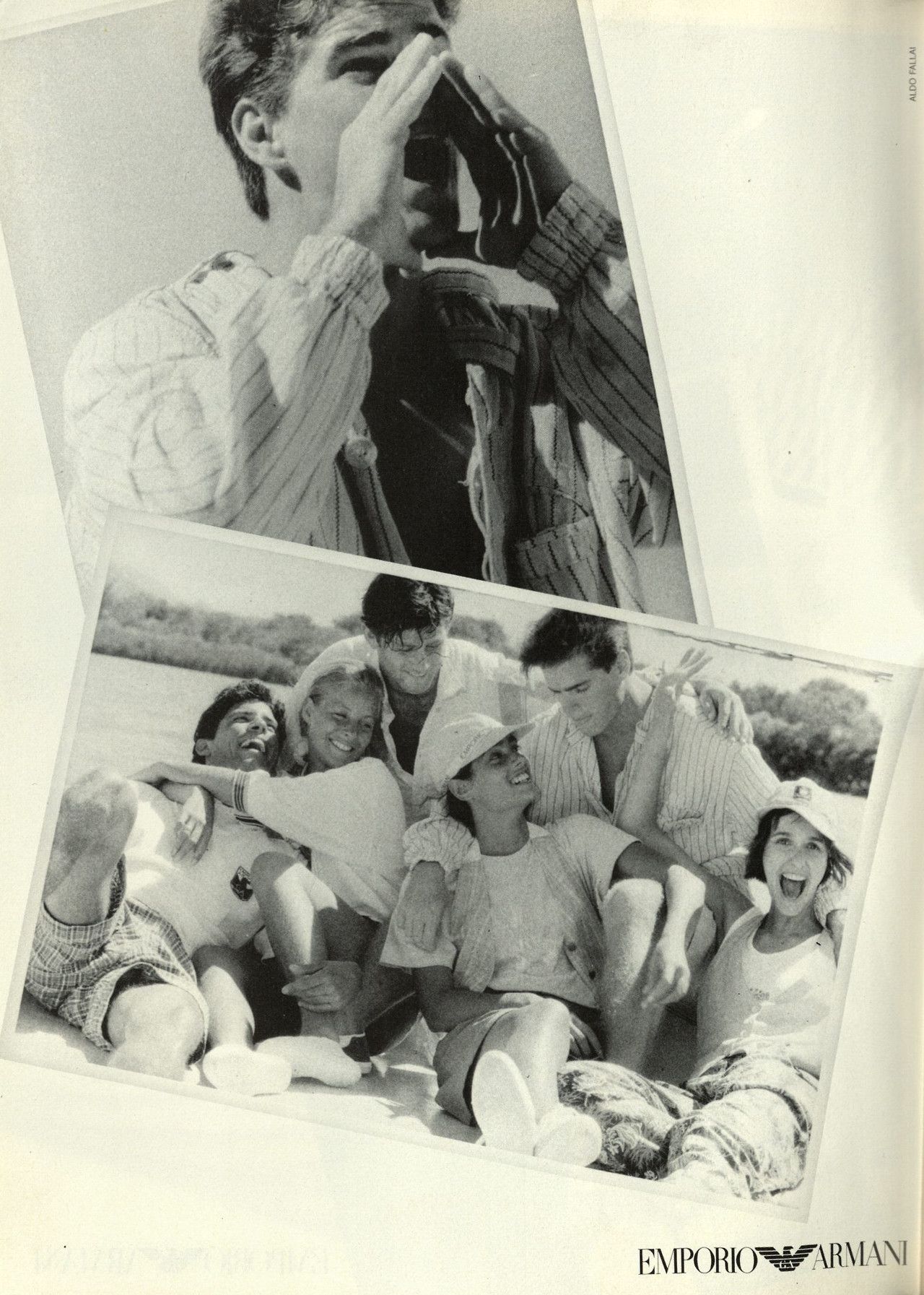

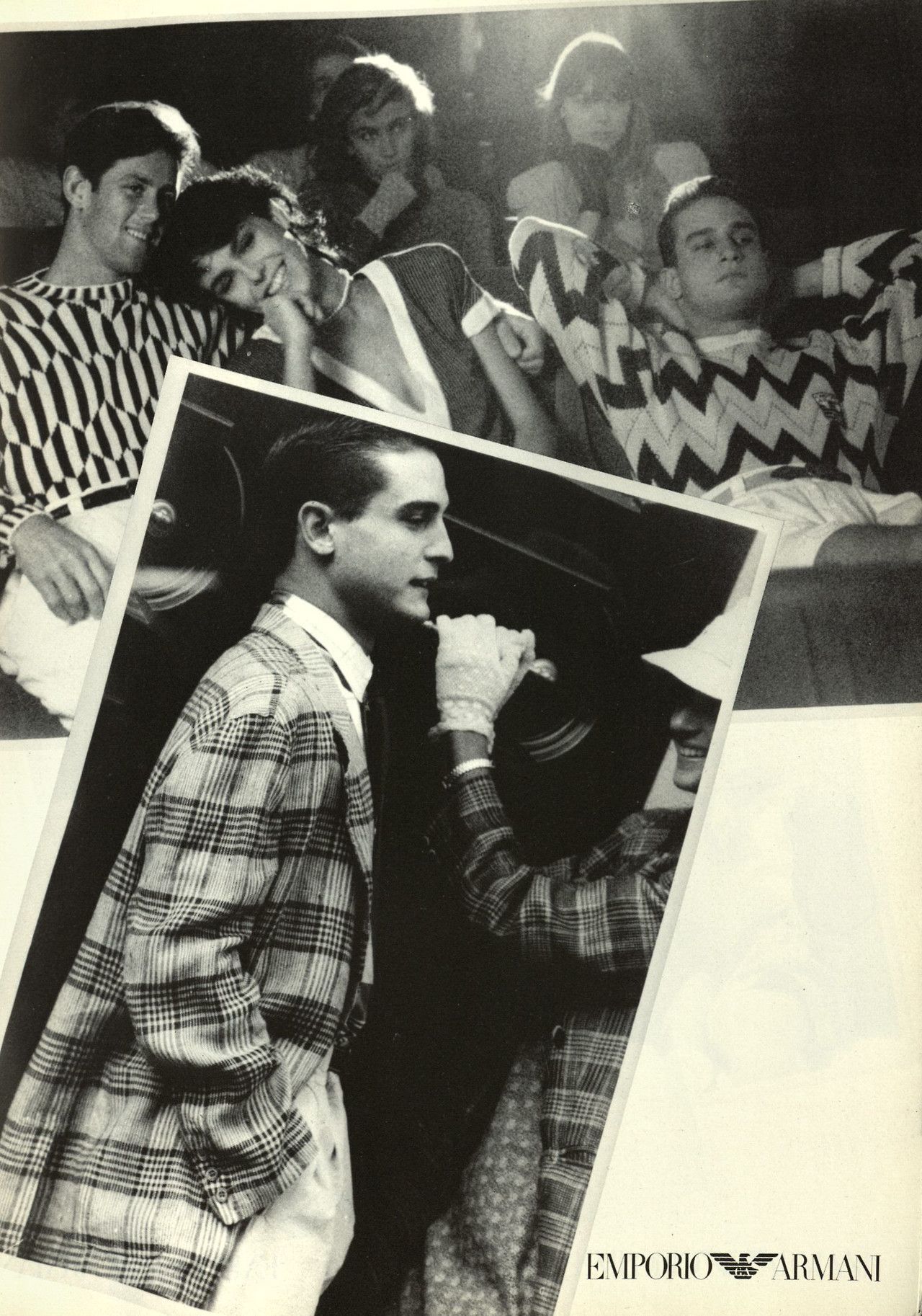

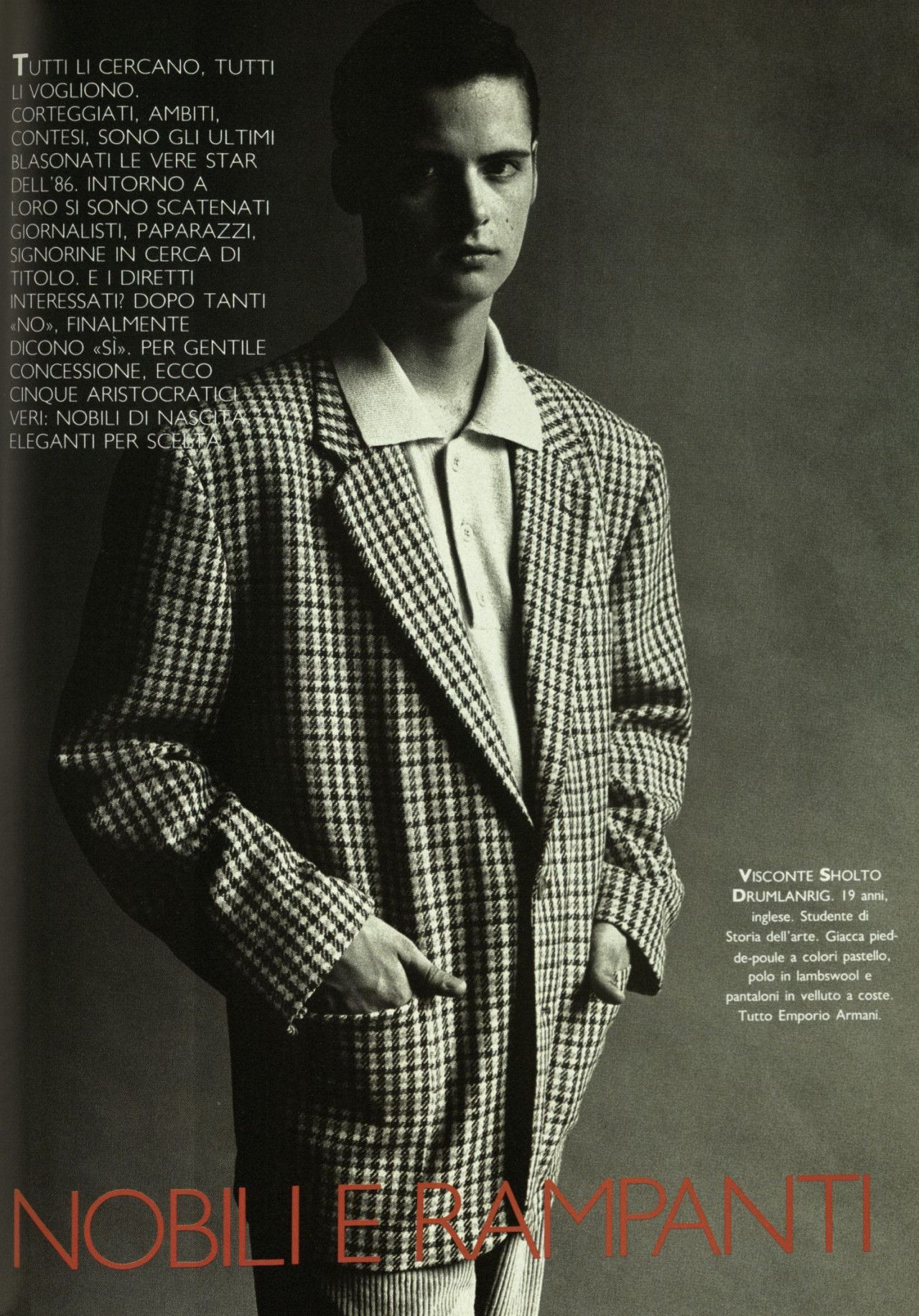

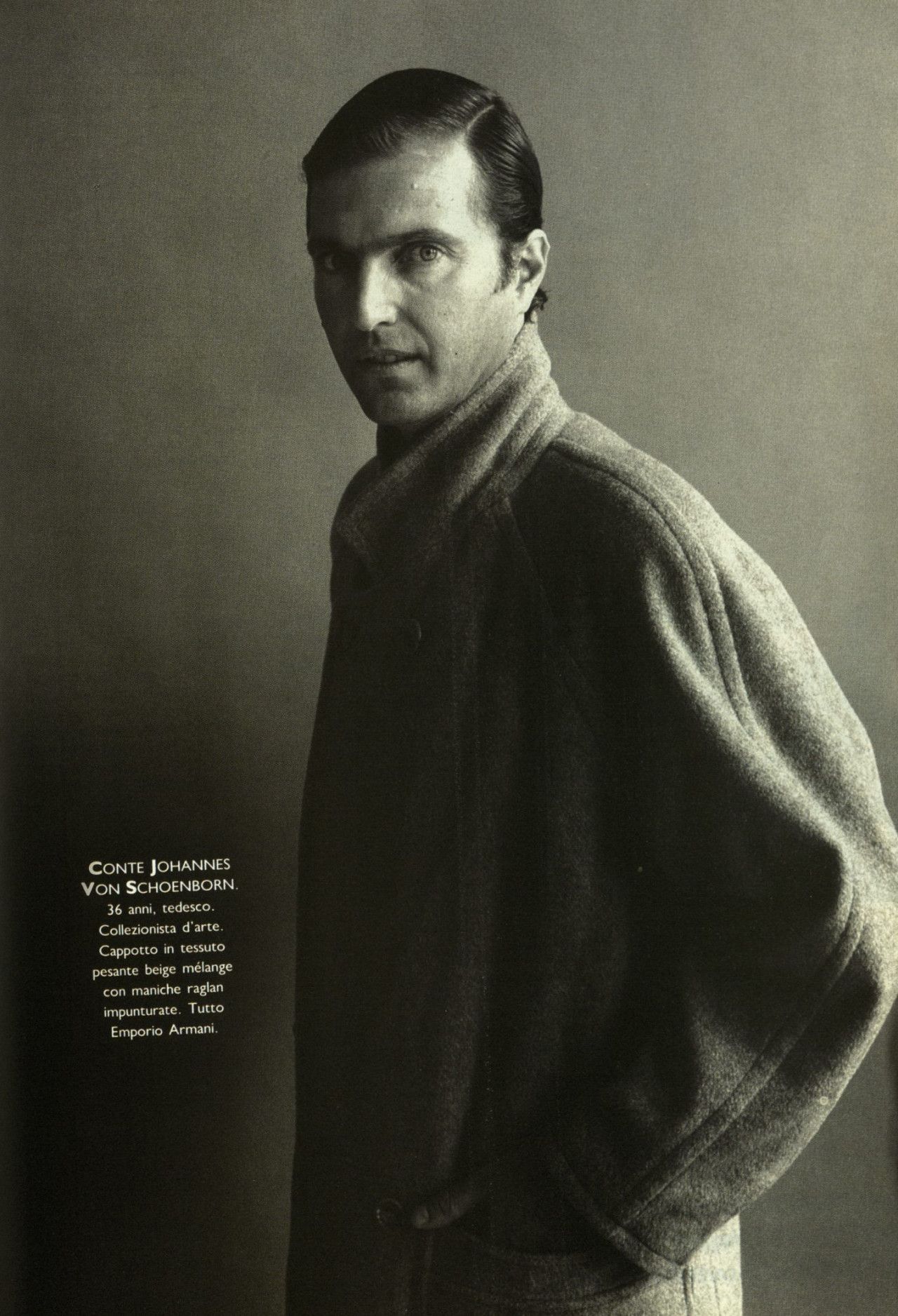

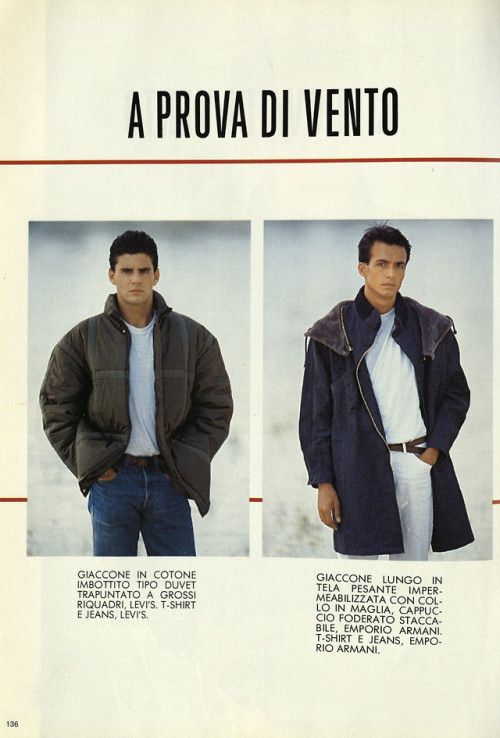

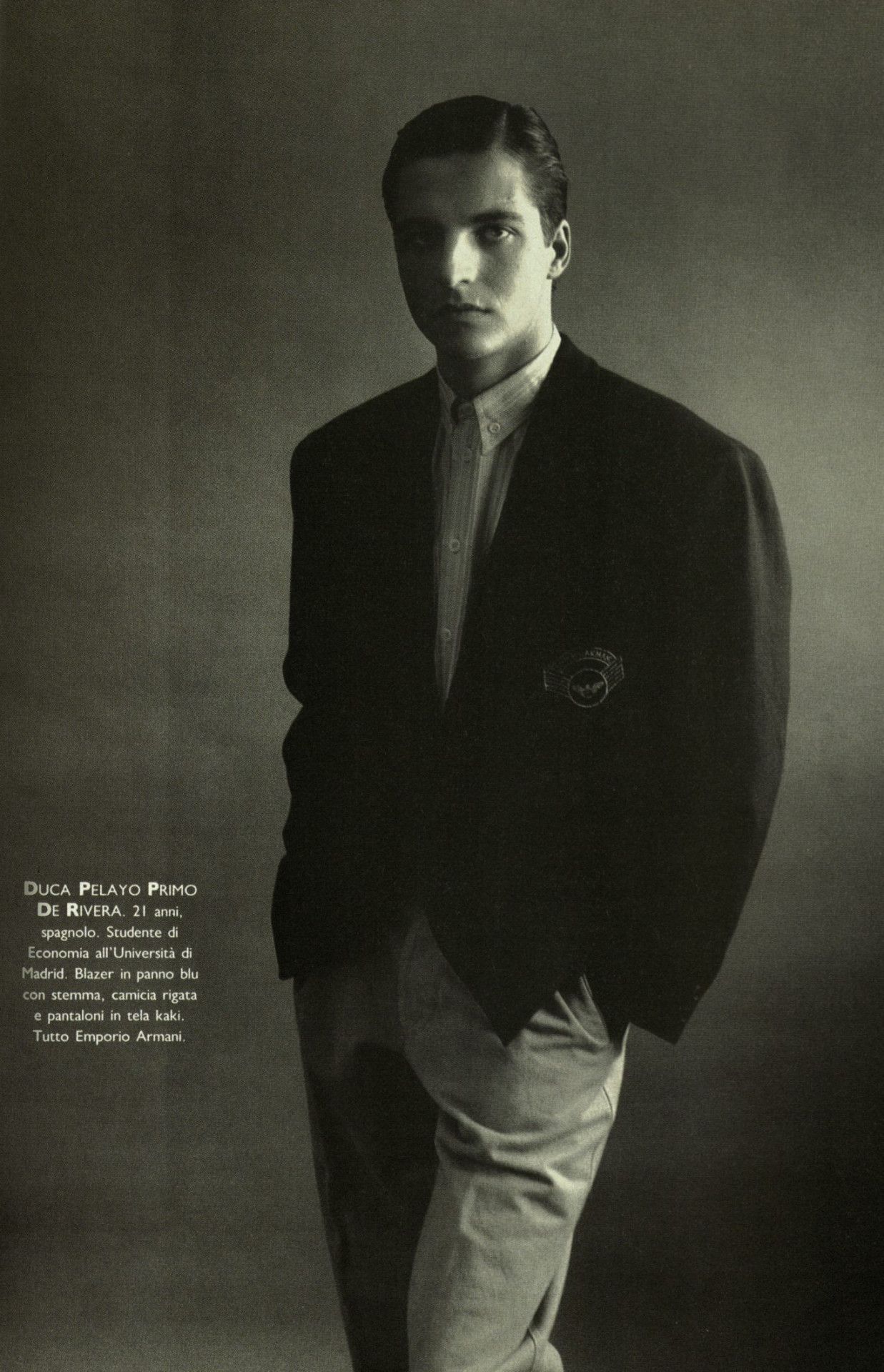

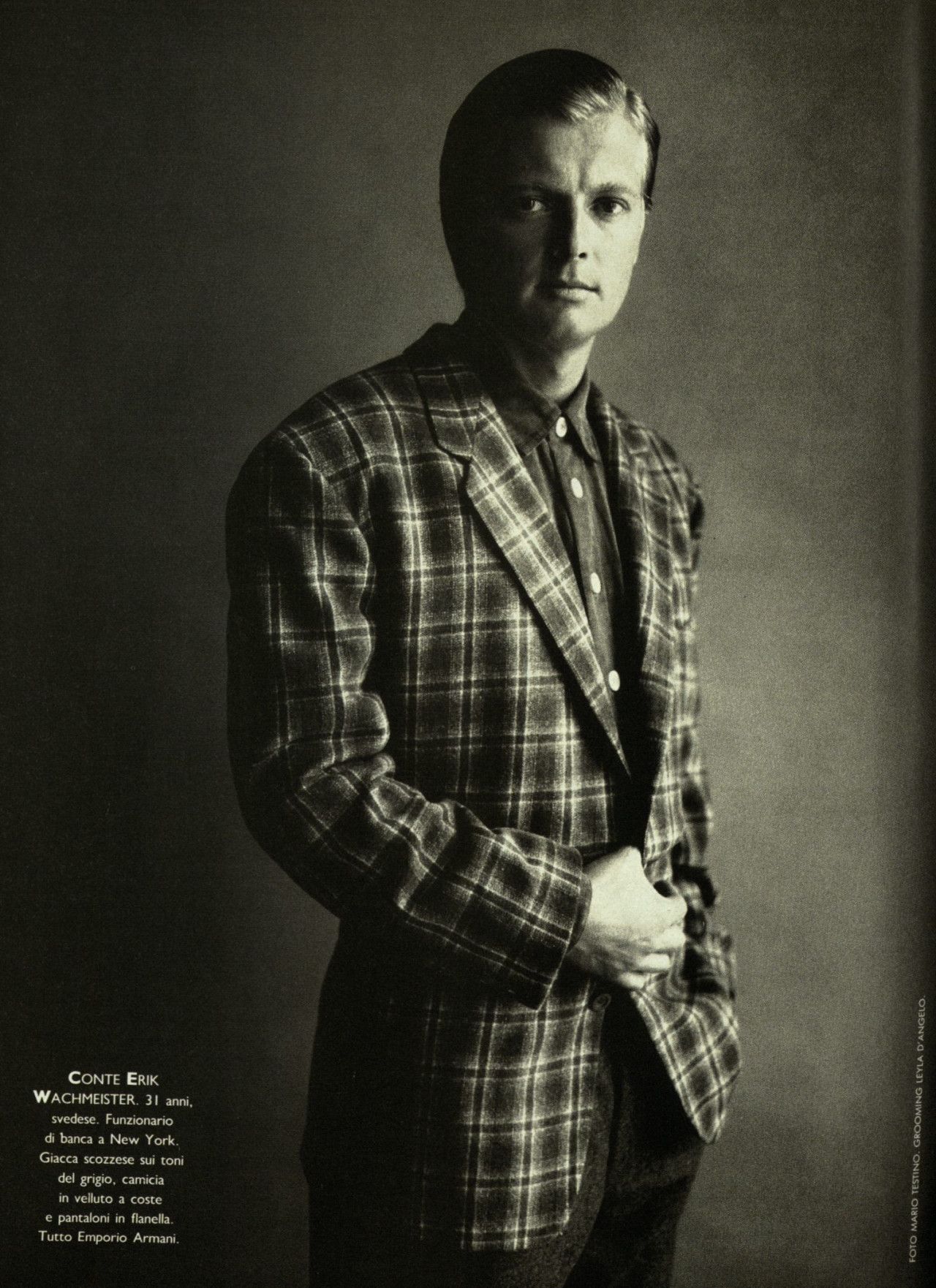

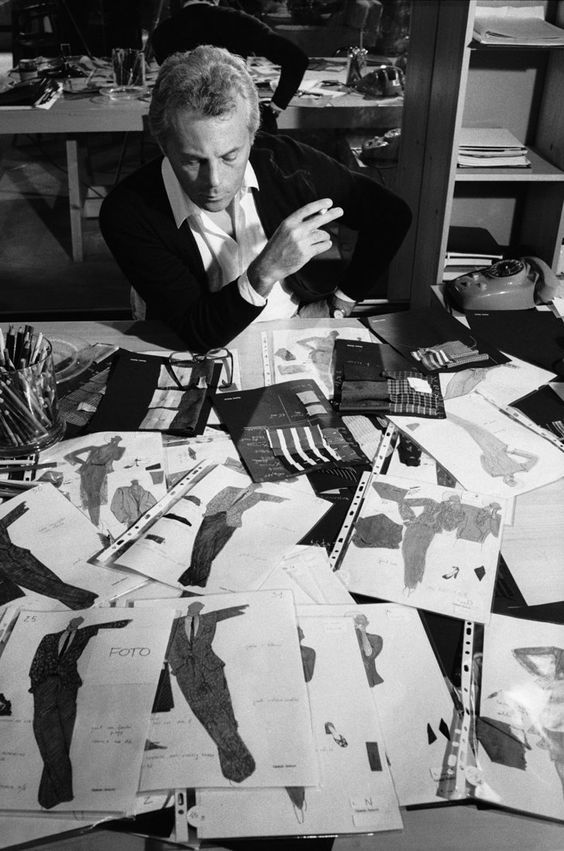

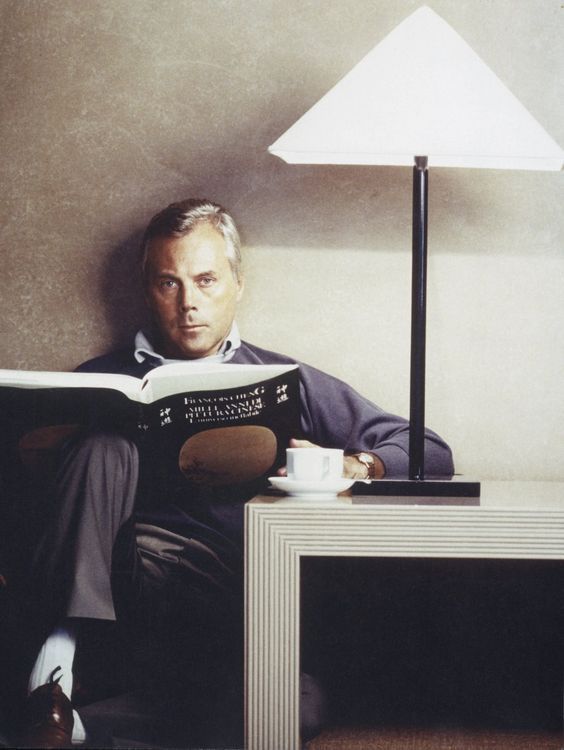

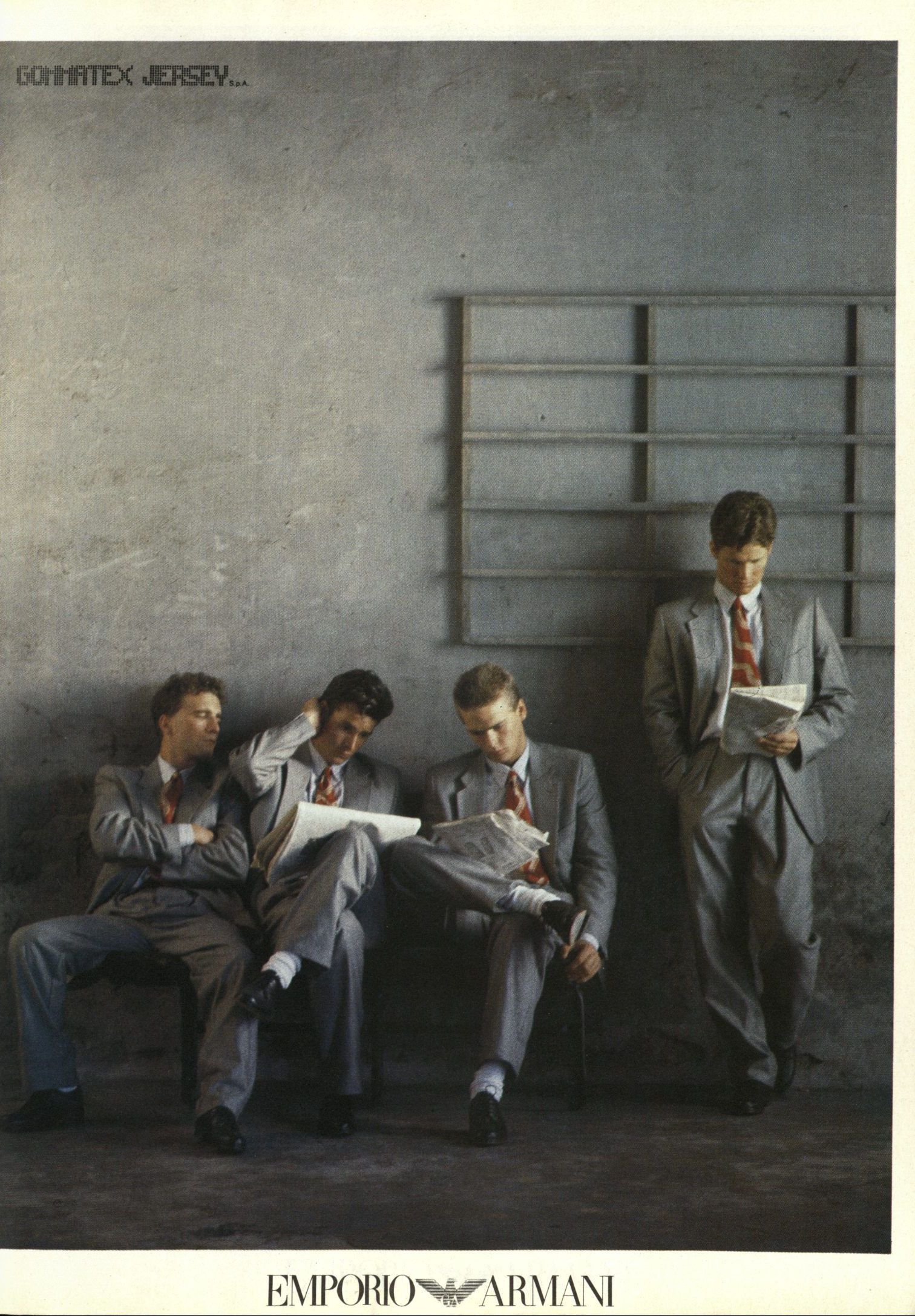

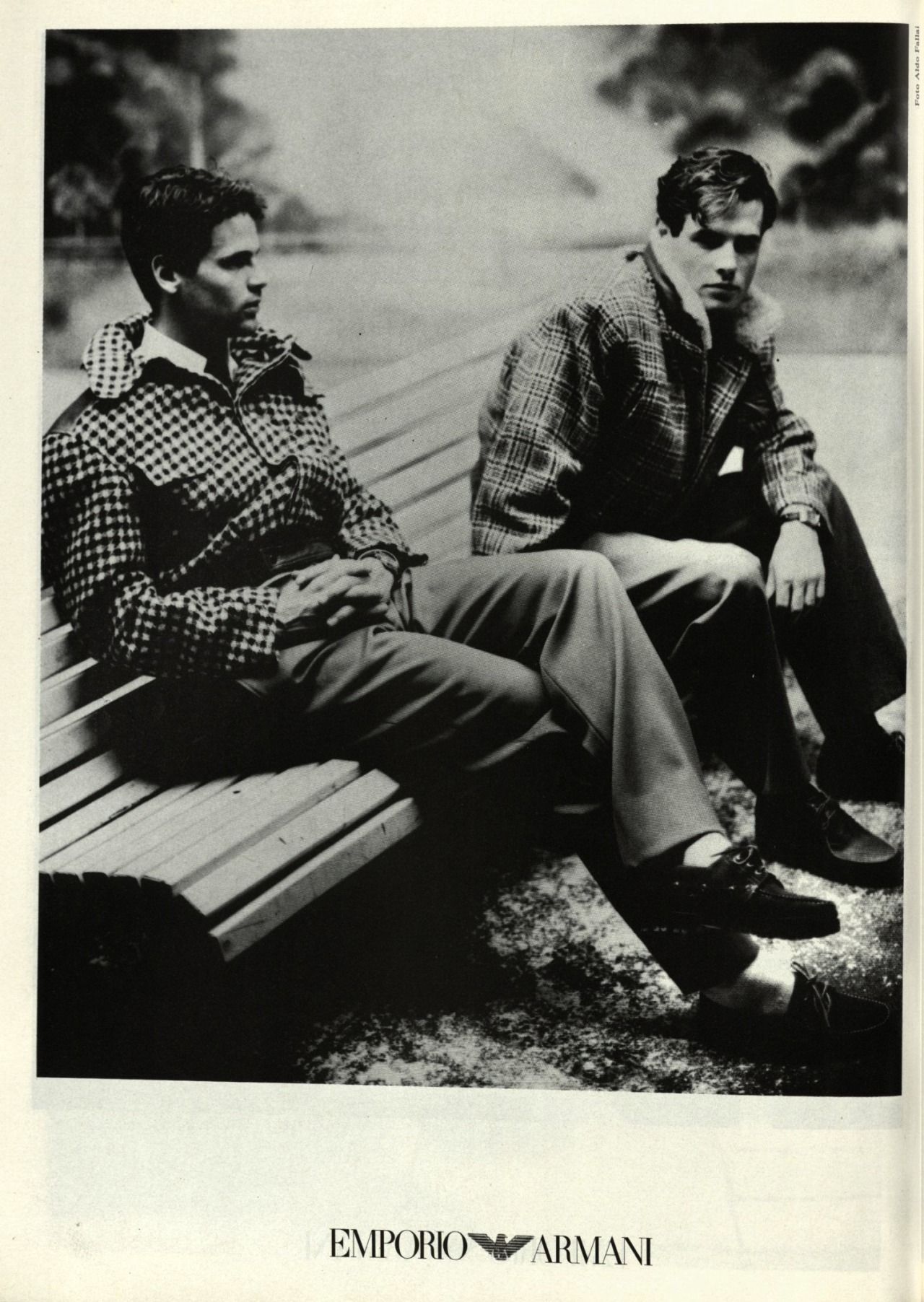

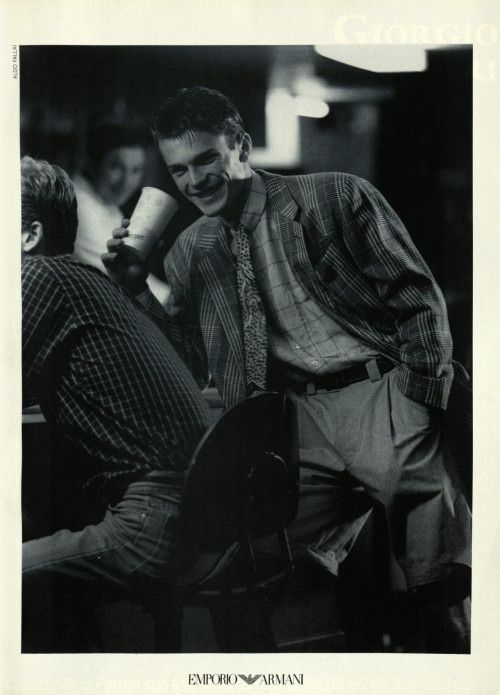

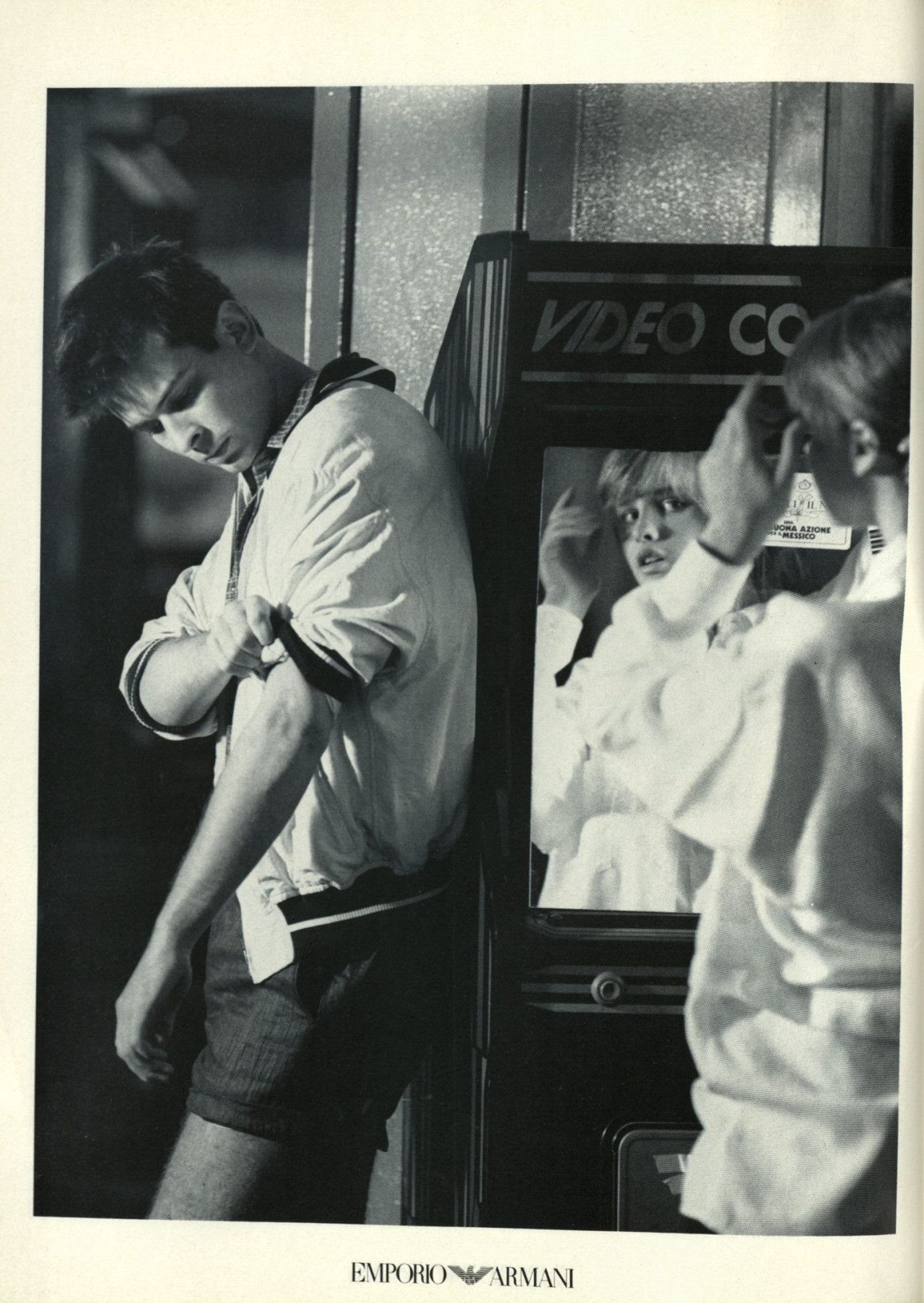

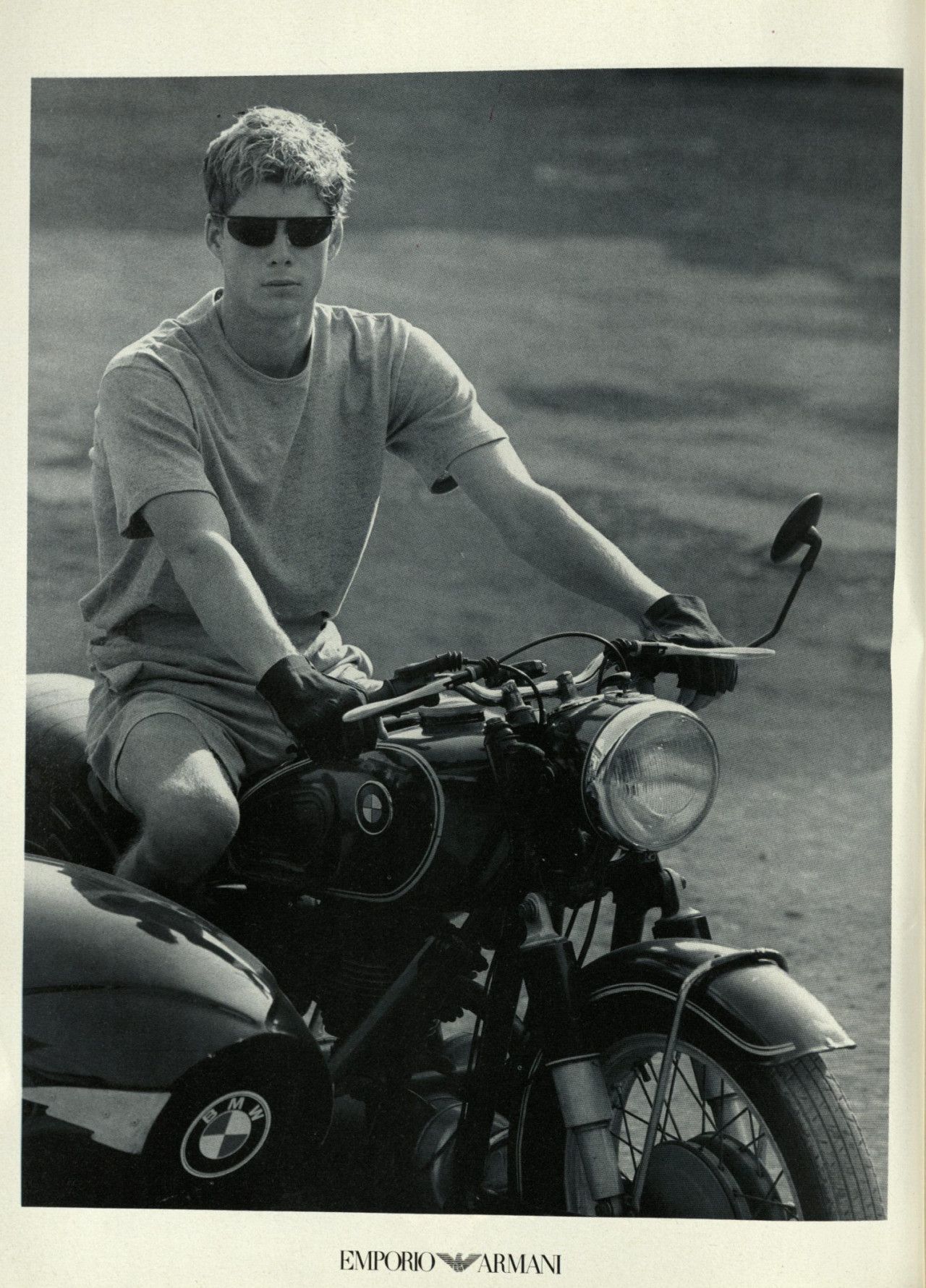

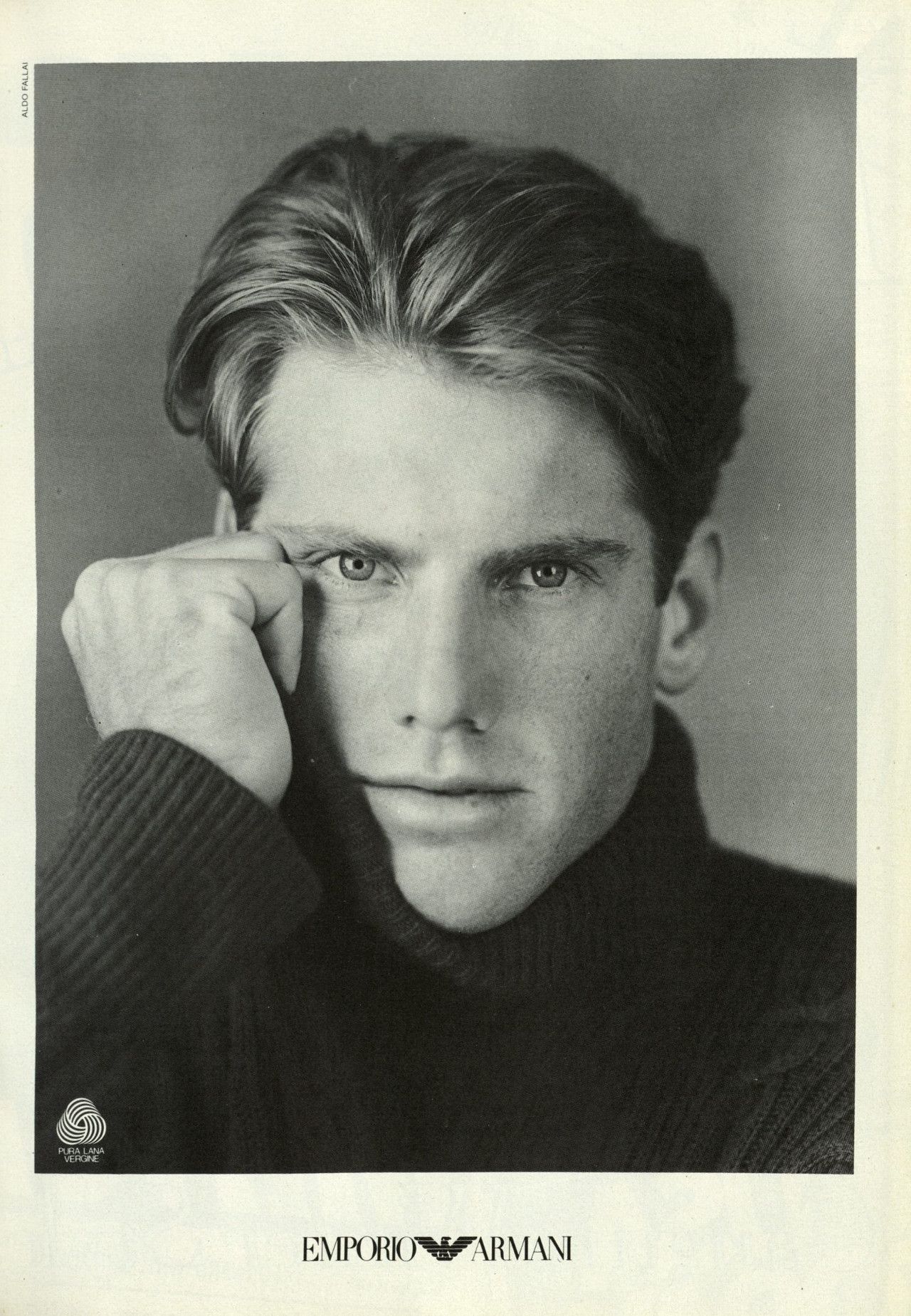

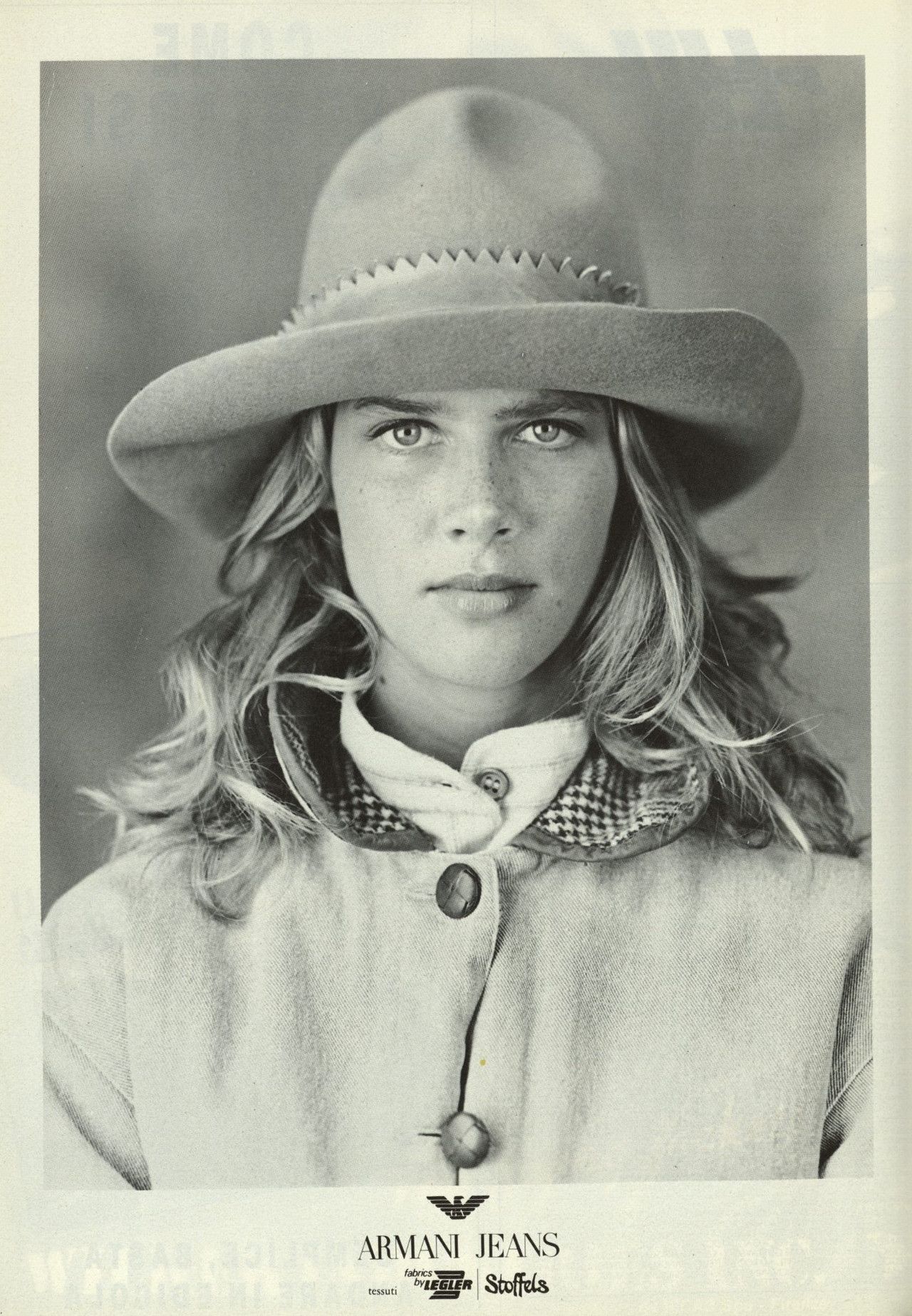

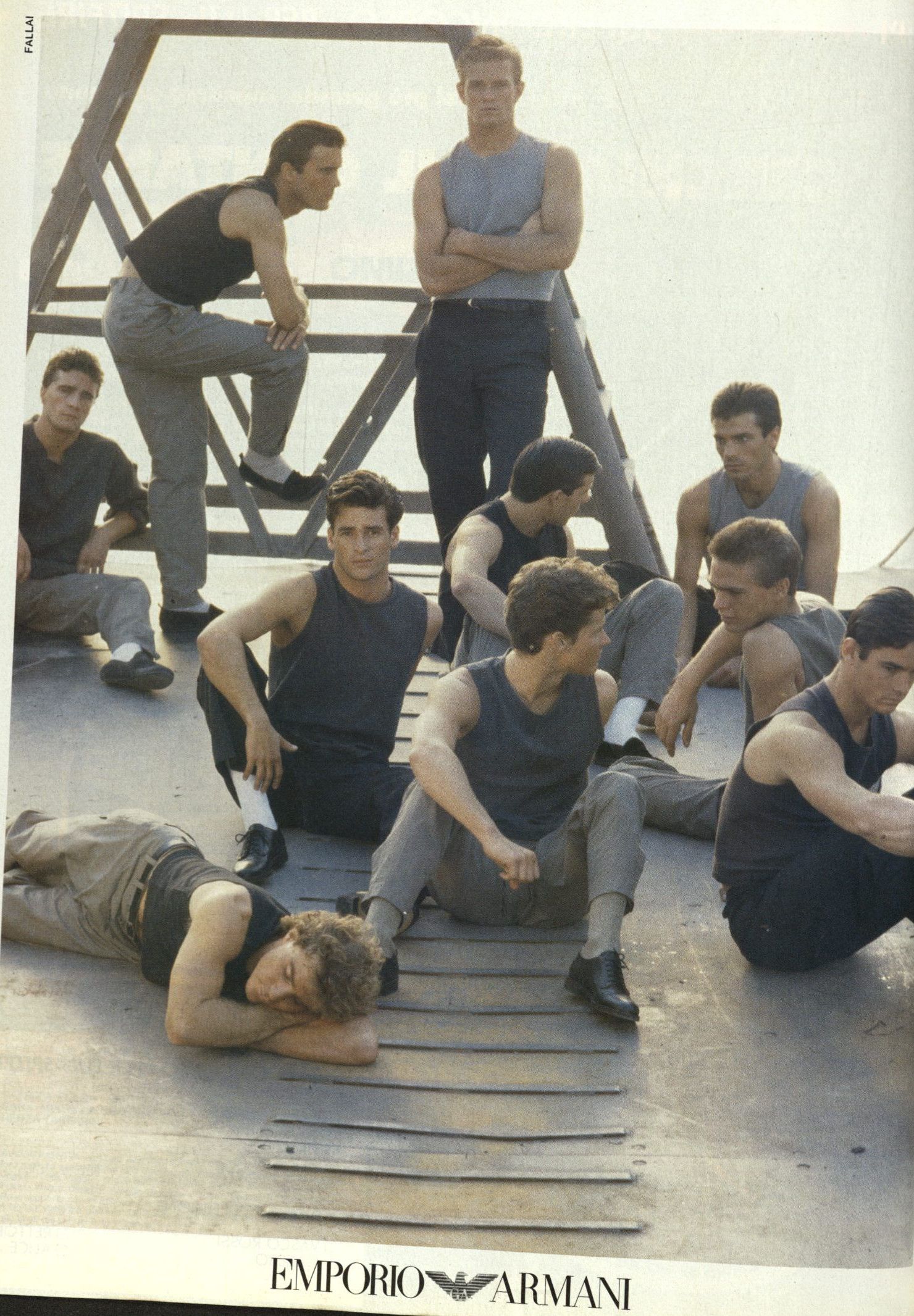

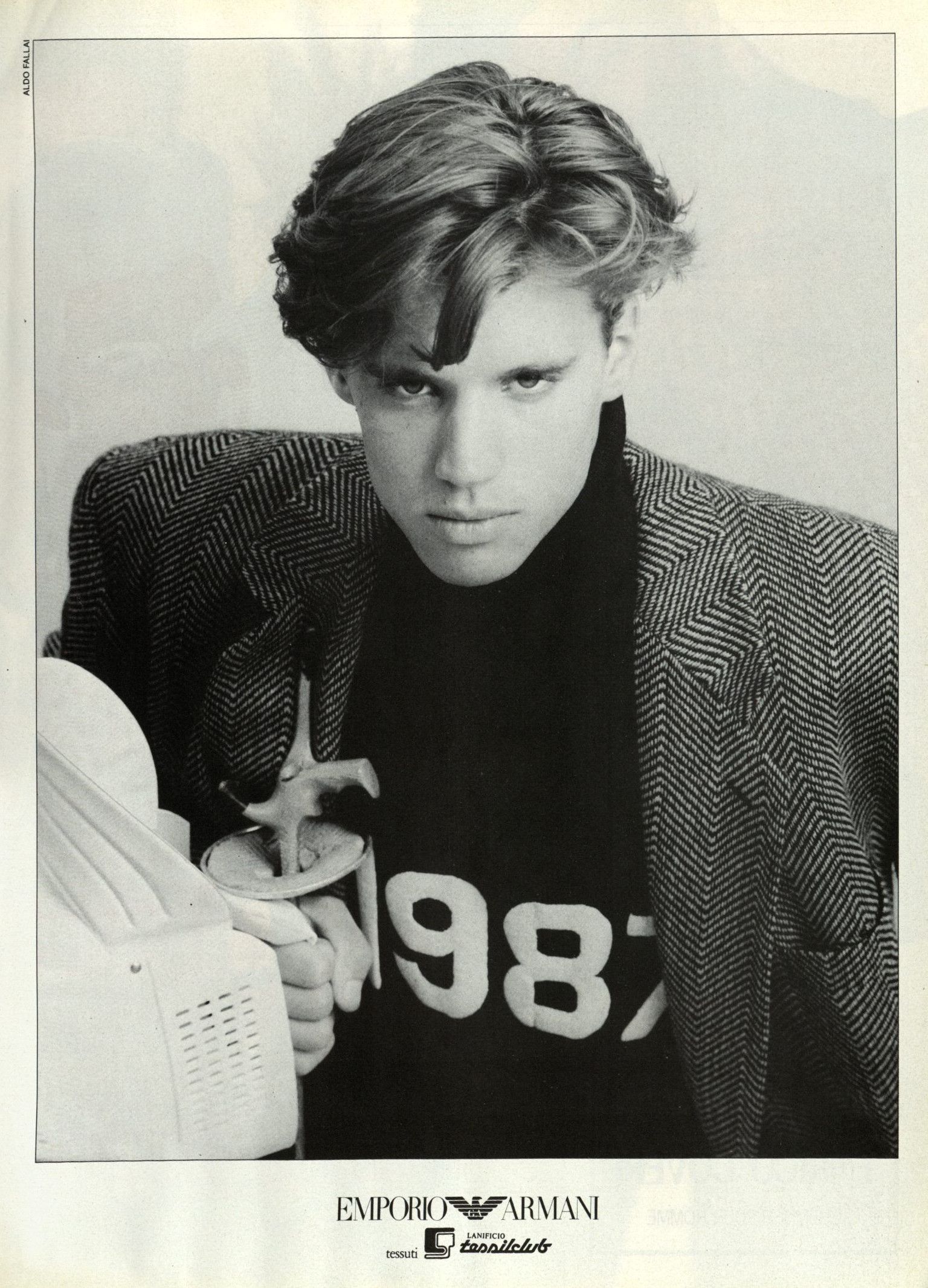

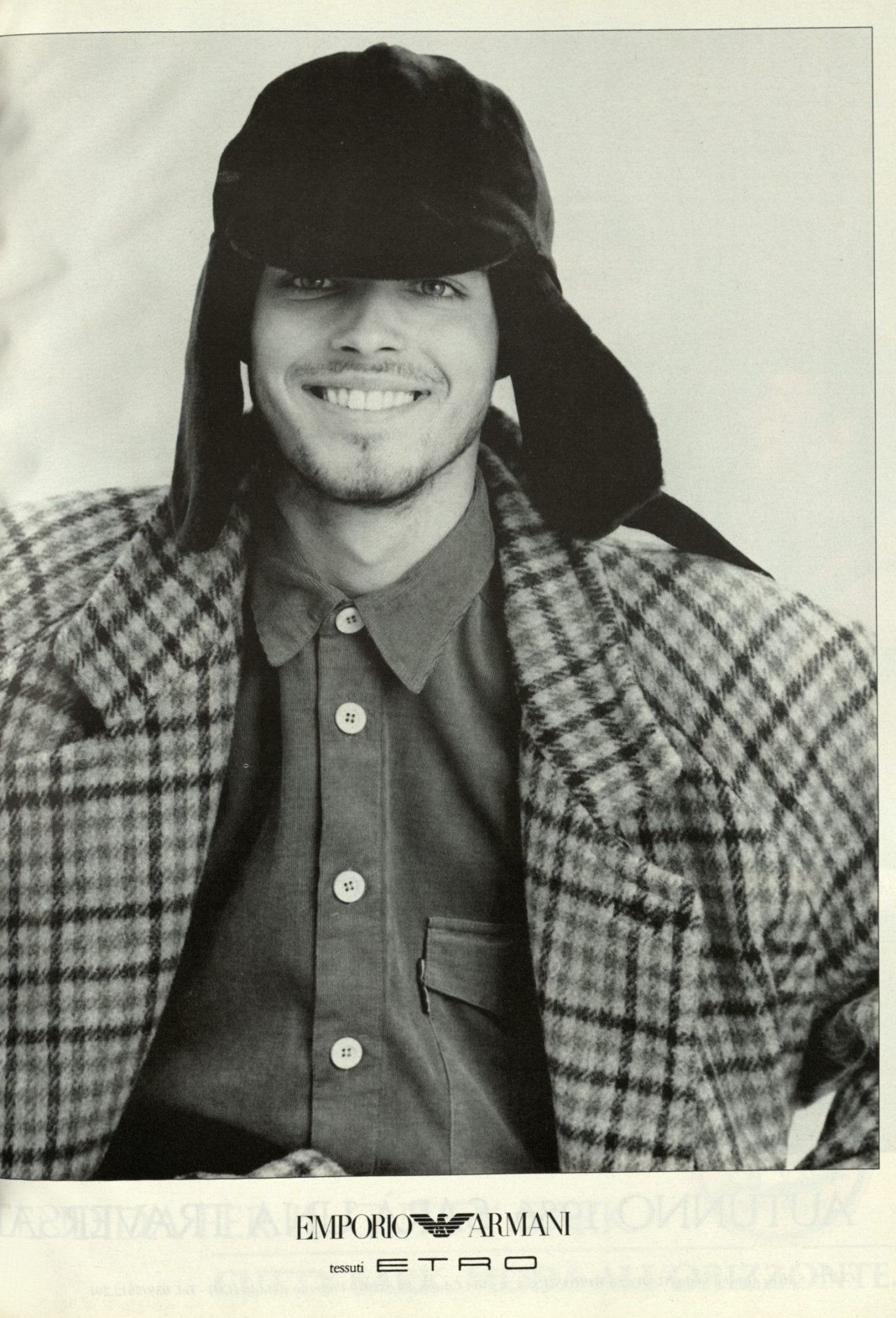

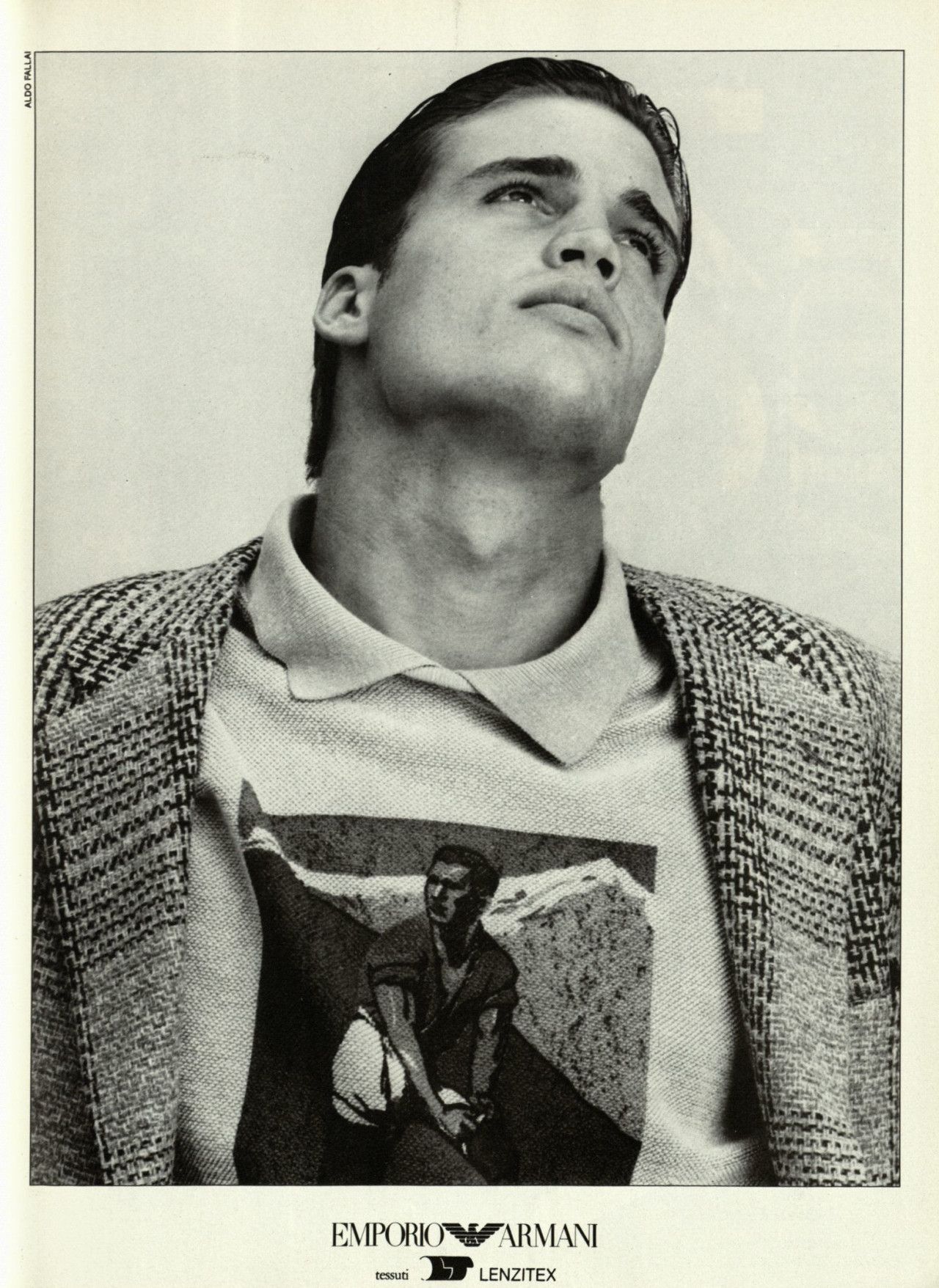

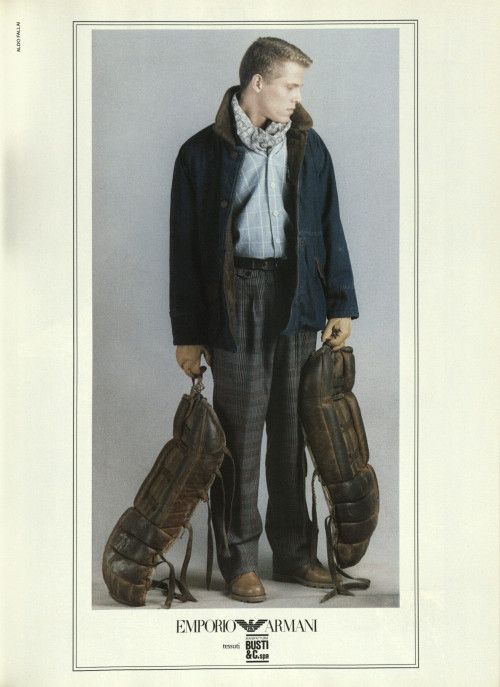

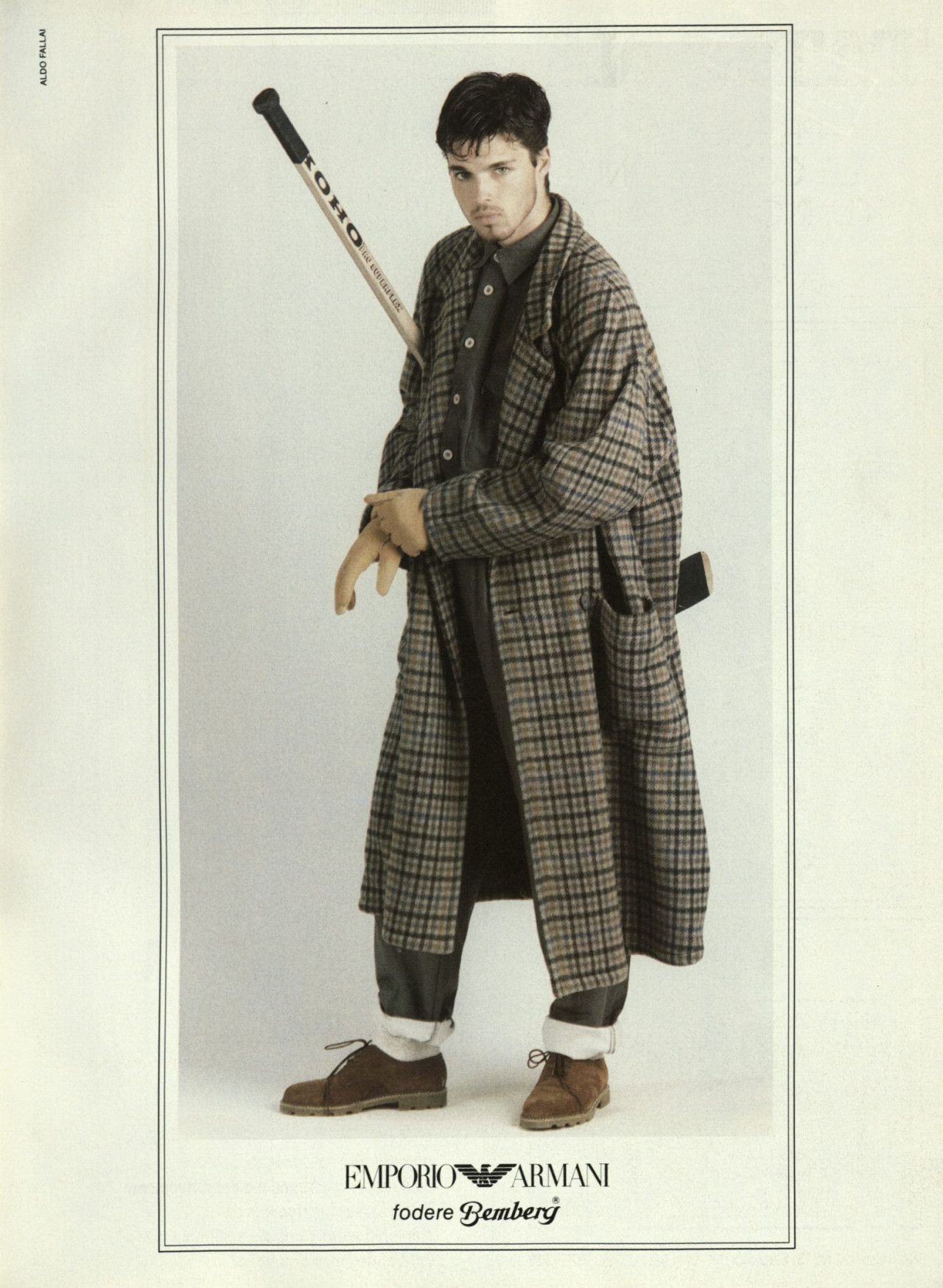

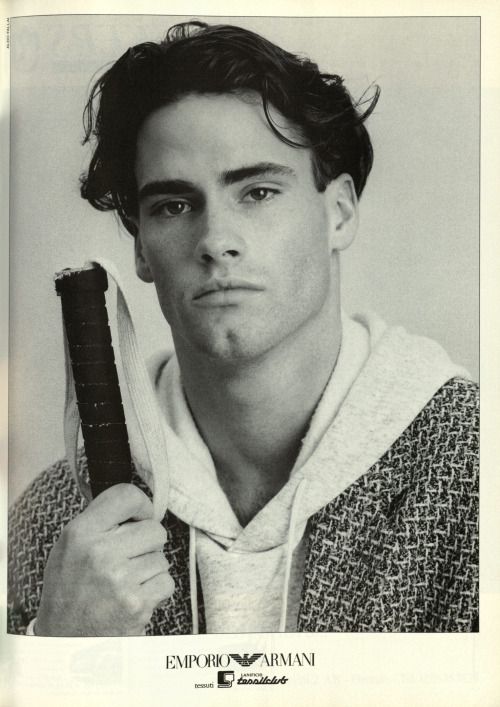

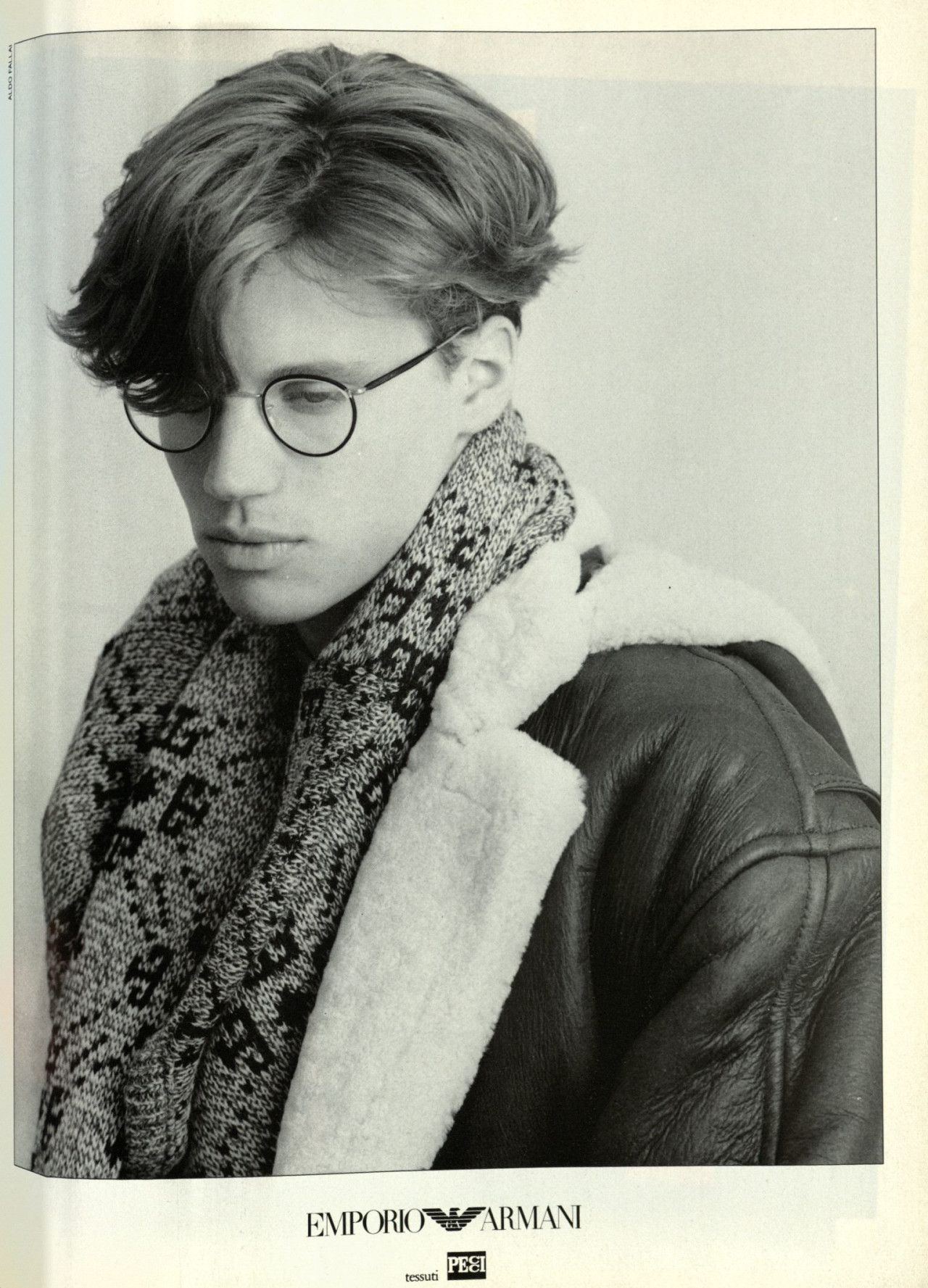

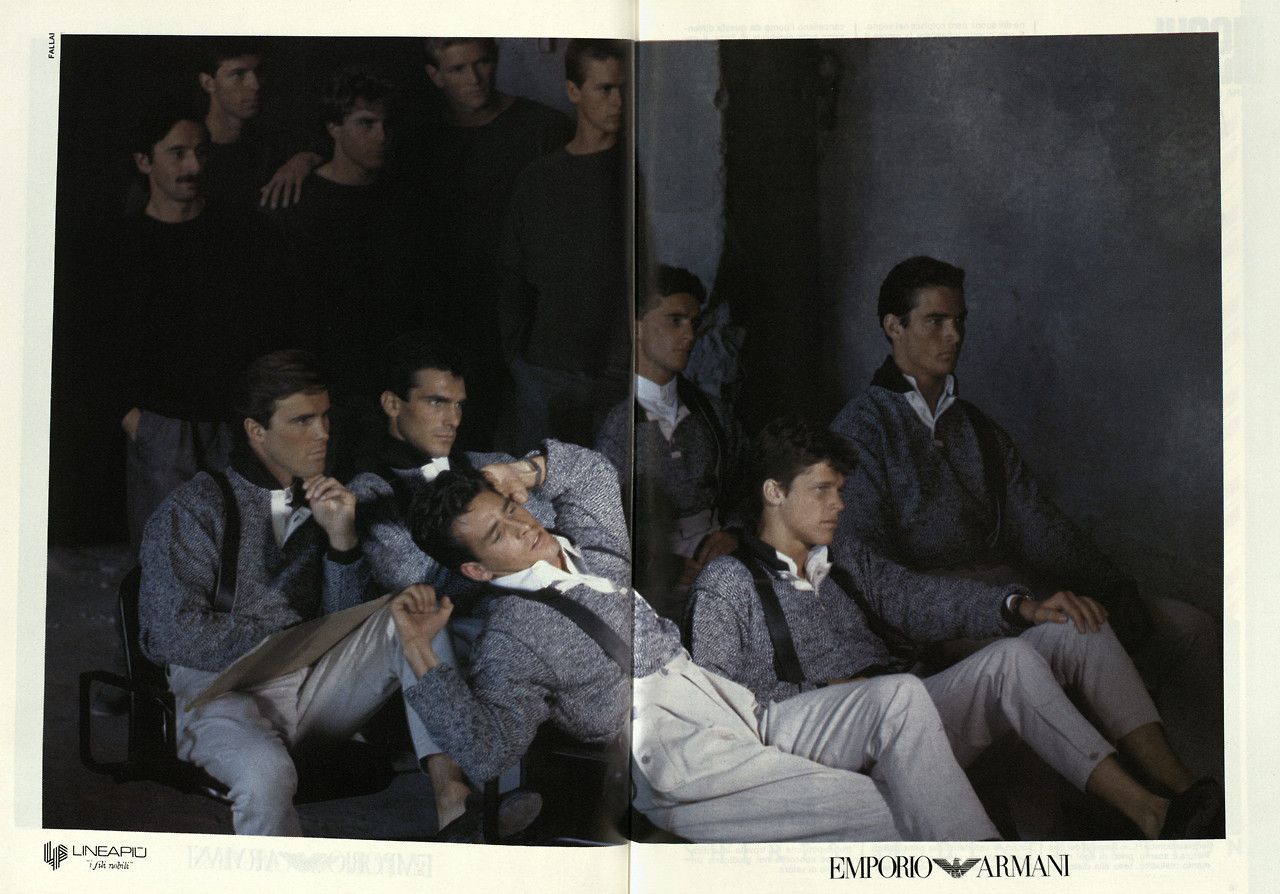

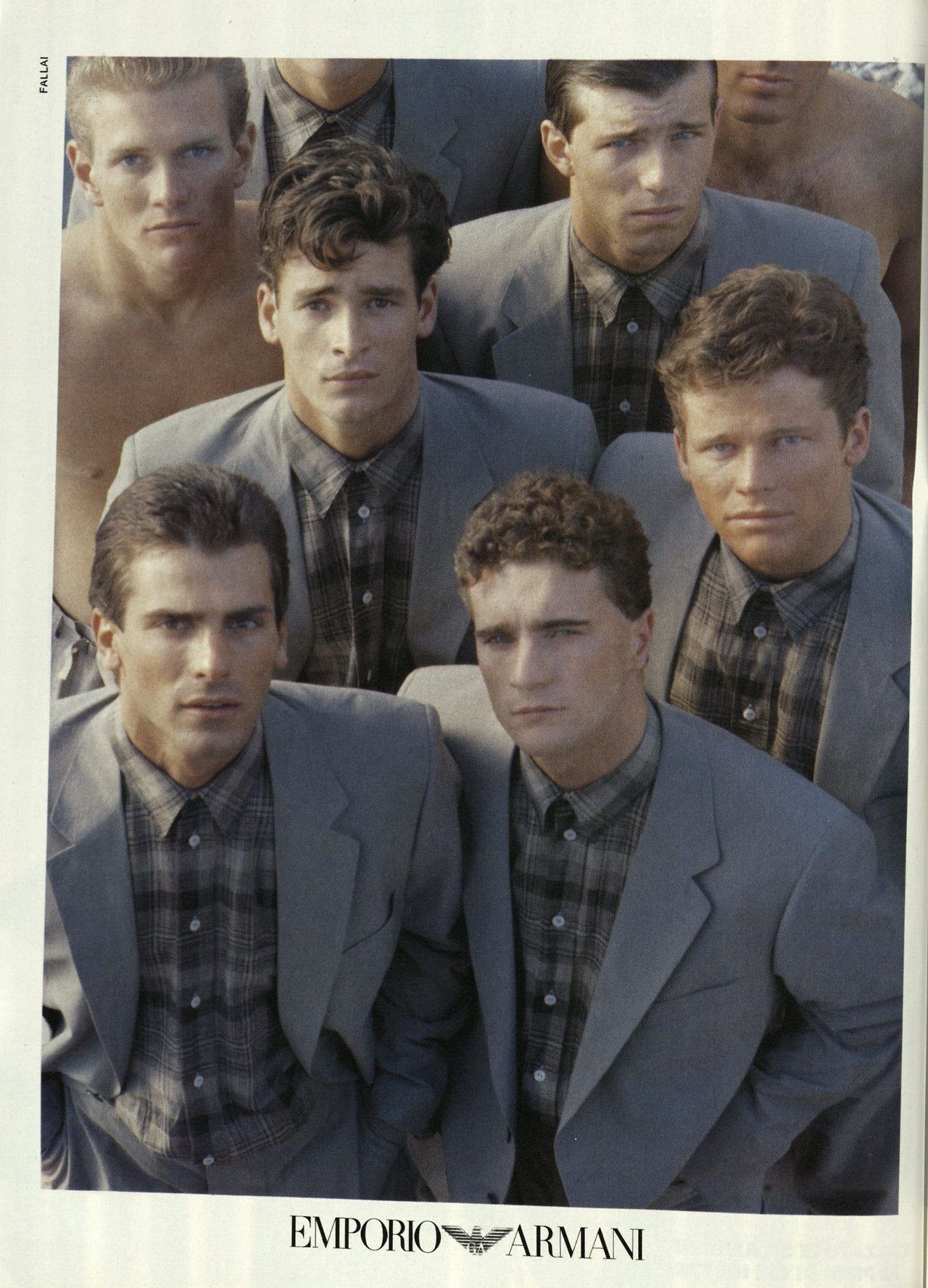

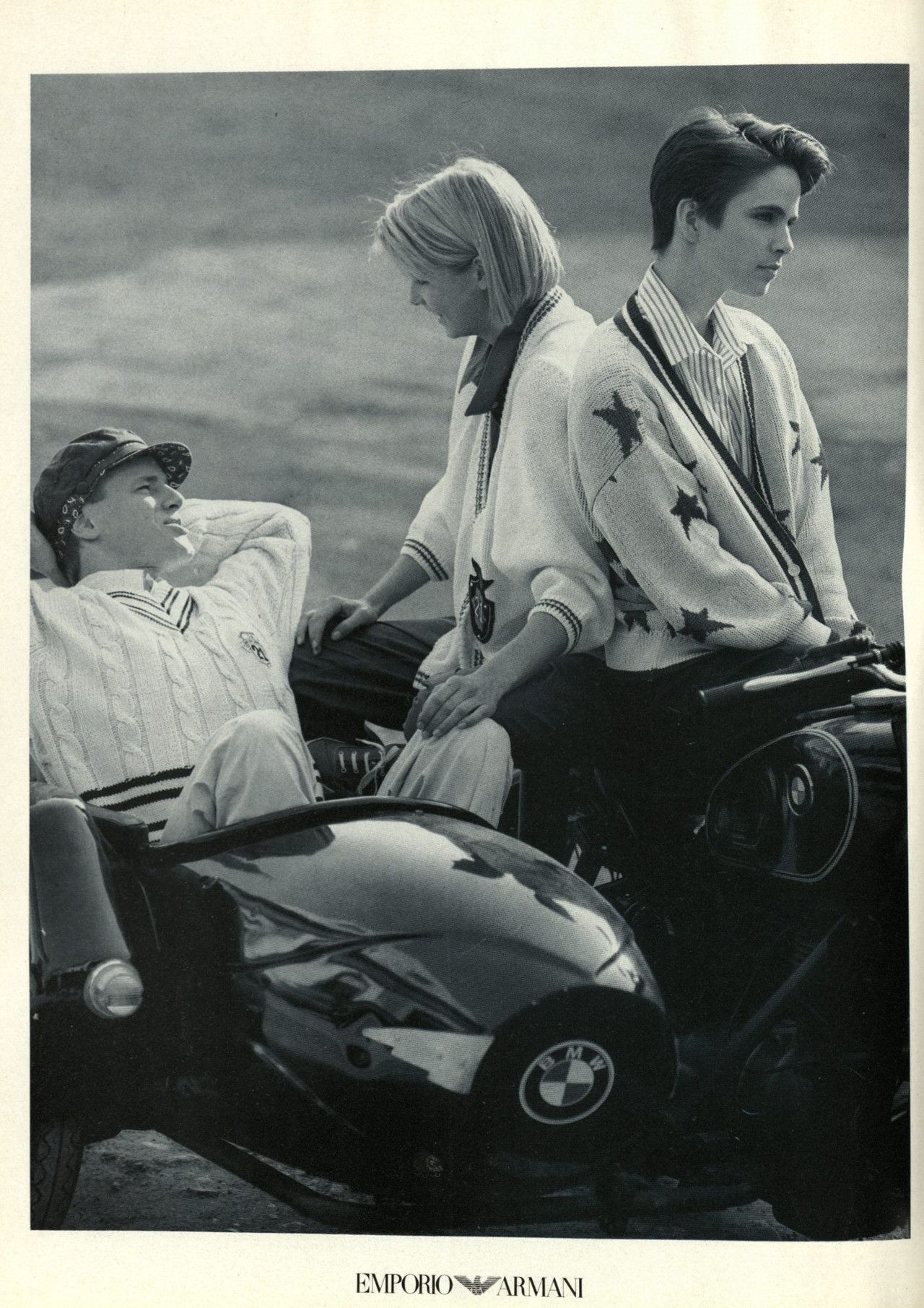

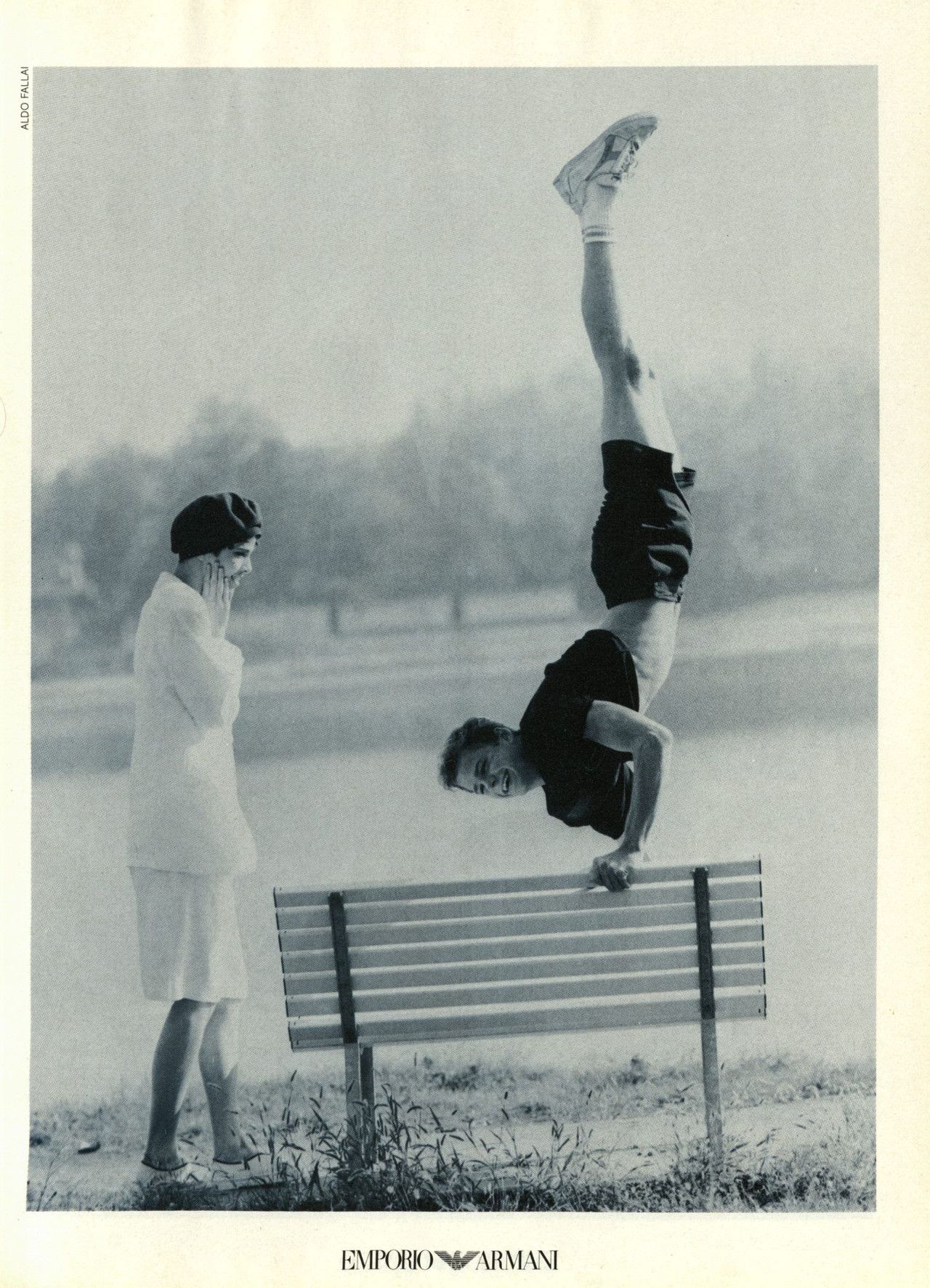

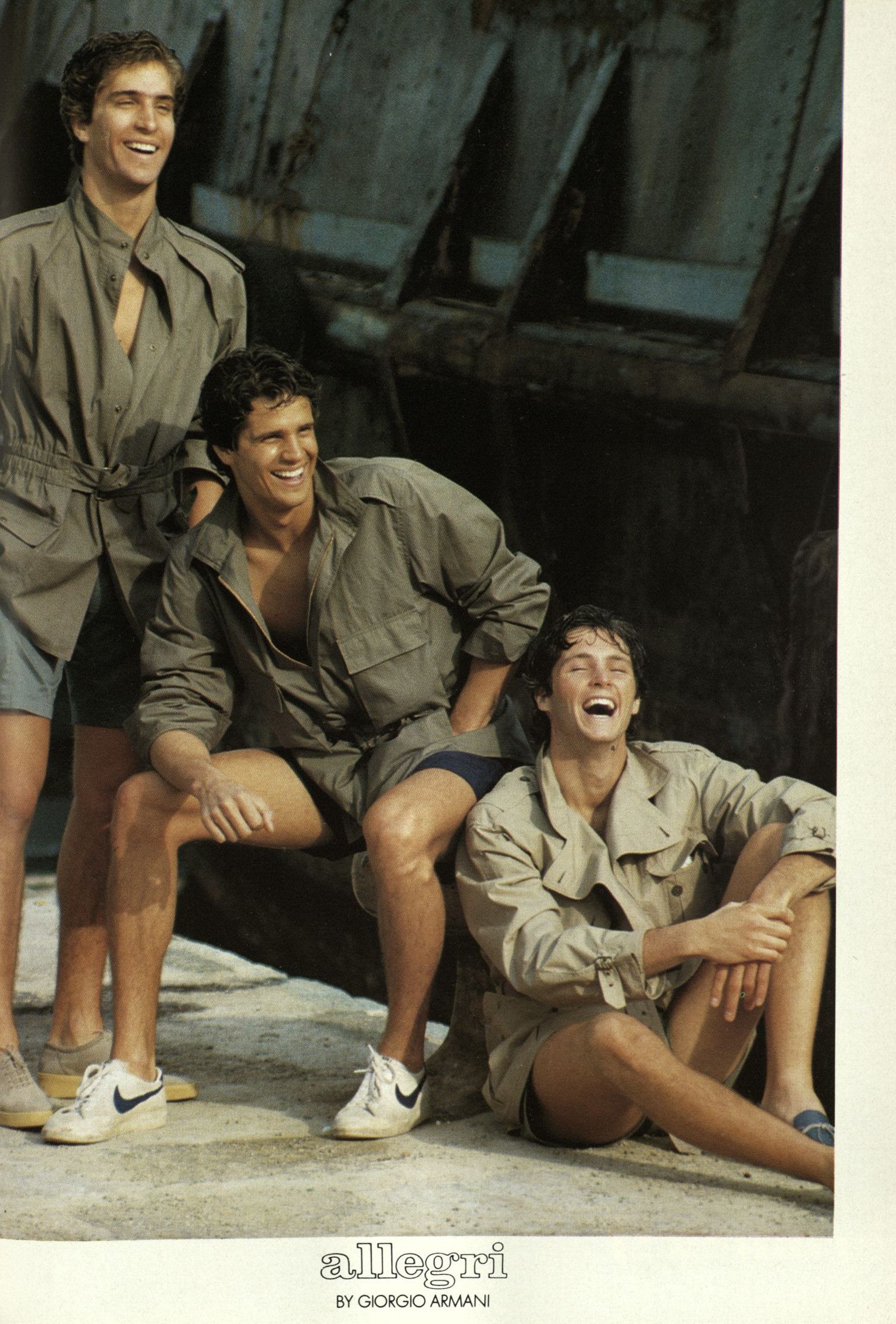

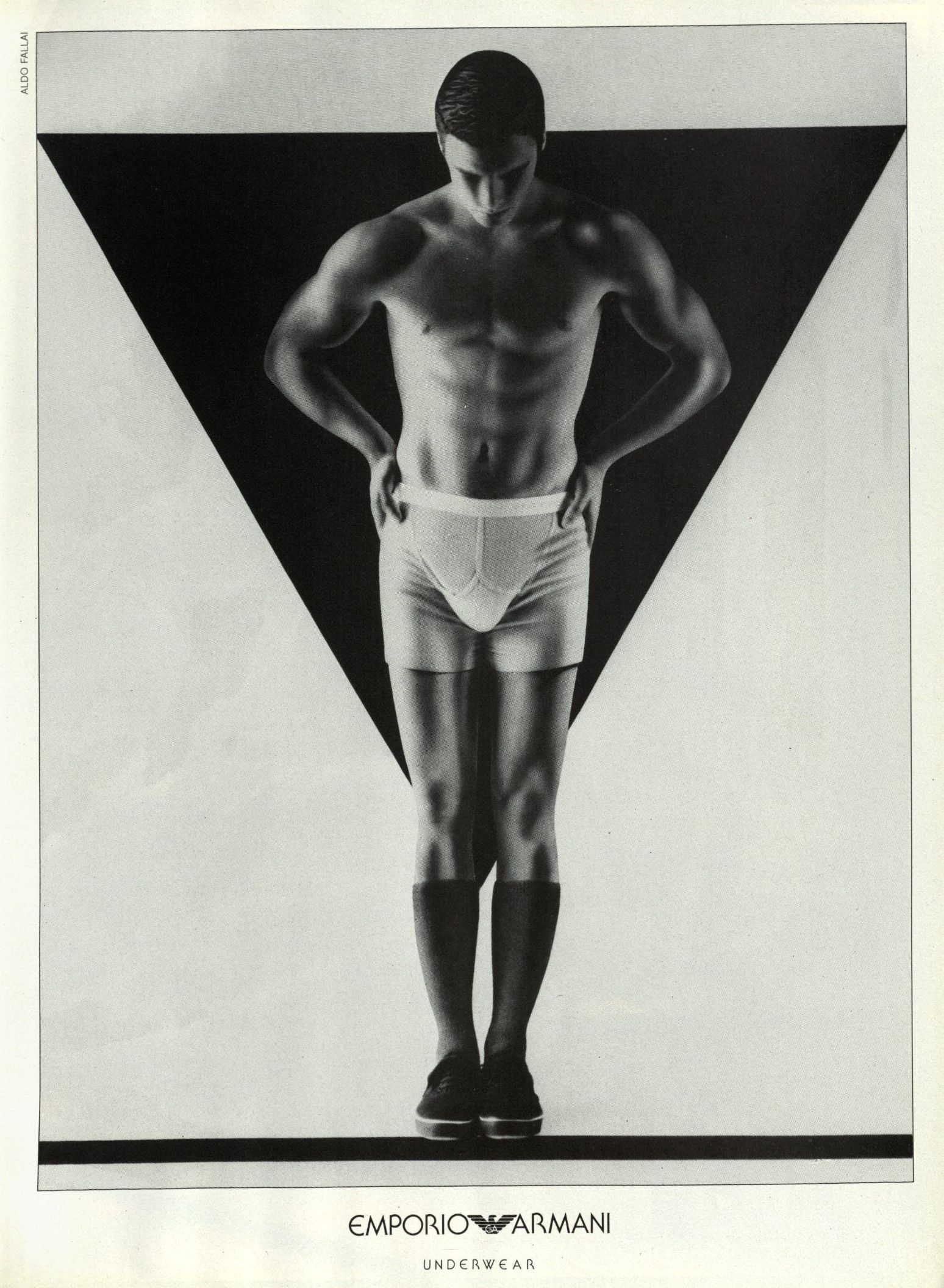

Armani had sensed that those young people would all be his customers if he could conceive of a luxury in hand but high - the success of Emporio Armani was planetary. If the campaigns and editorials dedicated to Giorgio Armani's mainline represented a more classic luxury, but always characterized by the typical softness and minimalism of the designer's suits, the storytelling that brought Emporio into the collective consciousness was different: through the lens of the legendary photographer Aldo Dellai, the posters and campaigns of the brand proposed a new, eclectic aesthetic that anticipated by years the gorpcore, the normcore, the world of Aimé Leon Dore and JJJJound and the sportswear logato – so much so that already around 1986, a fashion newspaper published the photo of a legion of young people in full look Emporio entitled The new elegants.

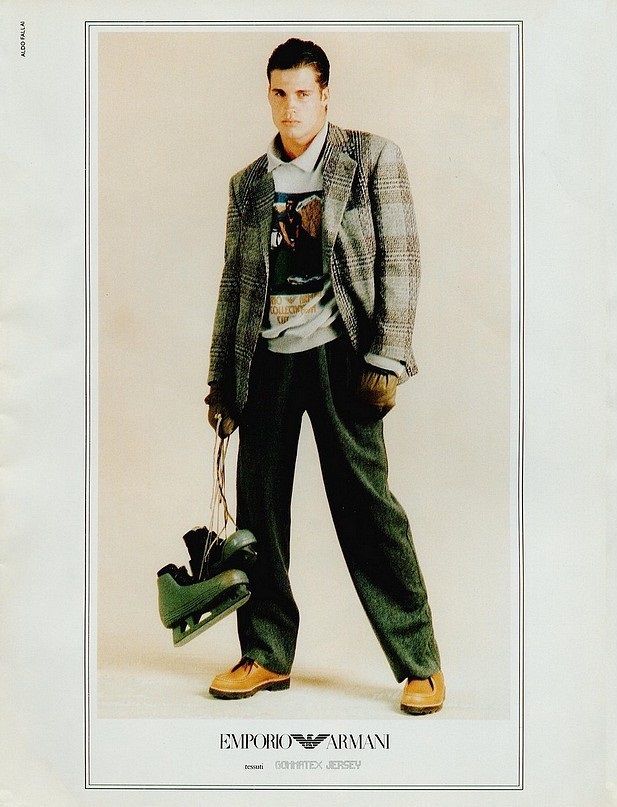

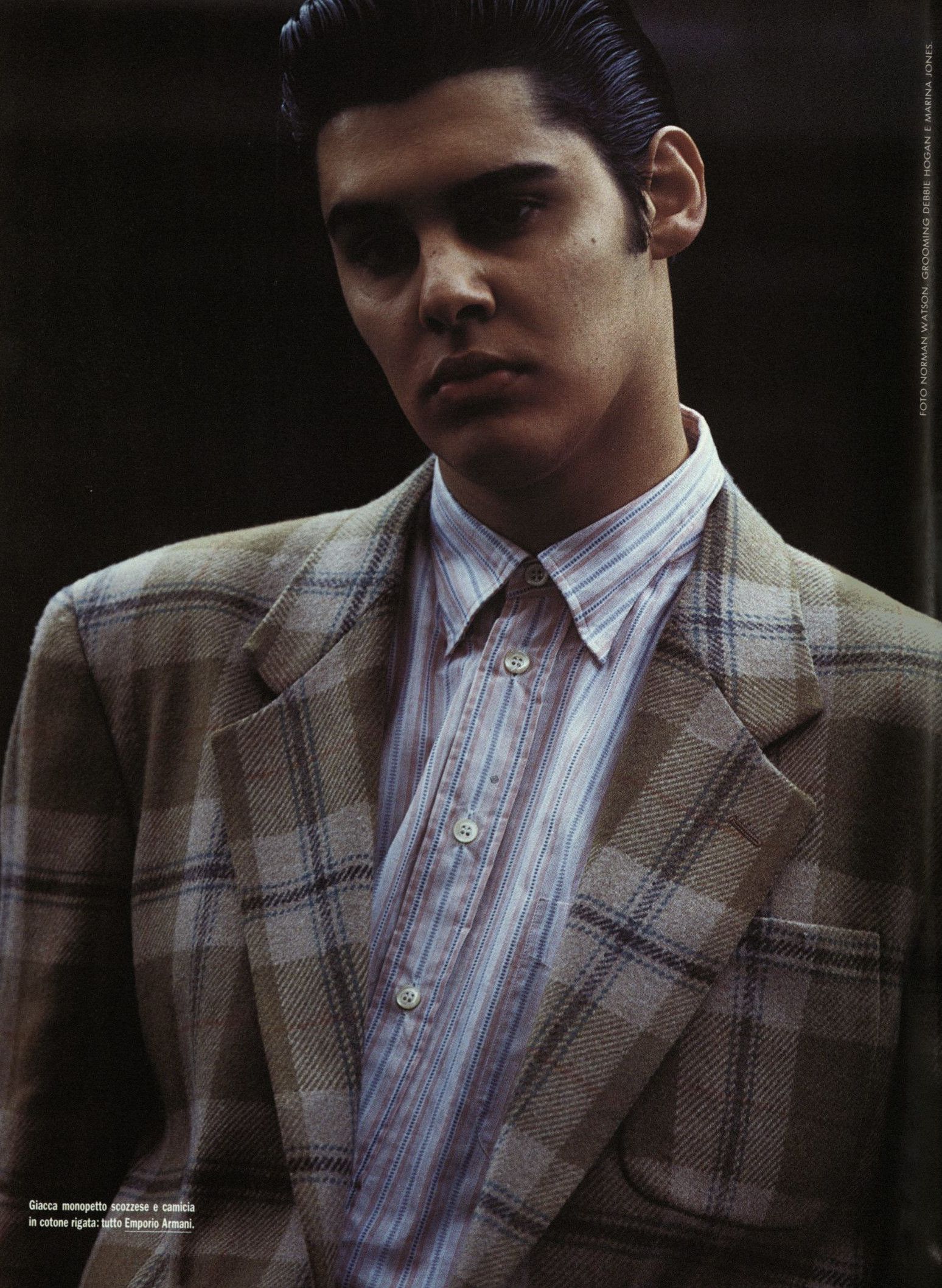

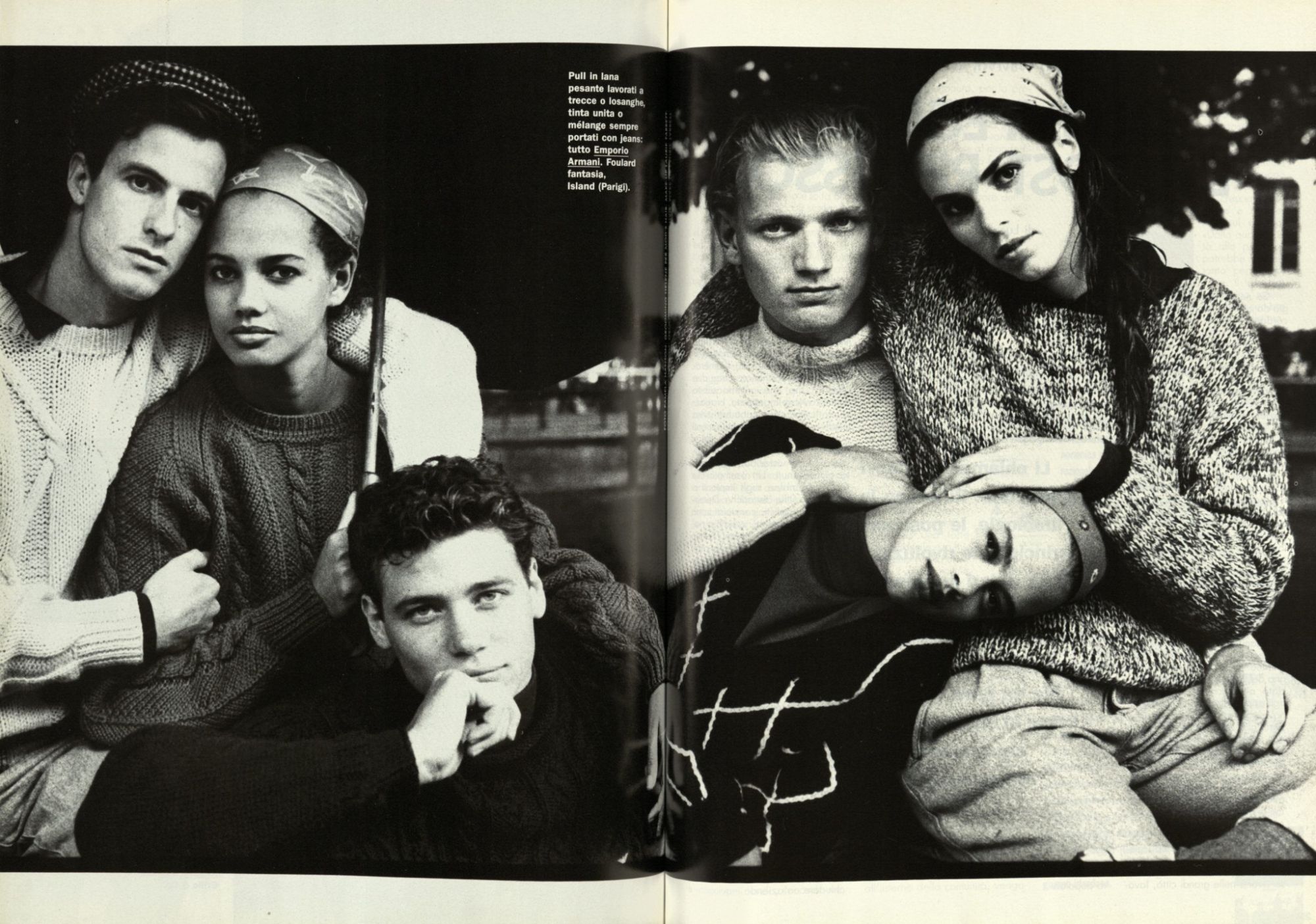

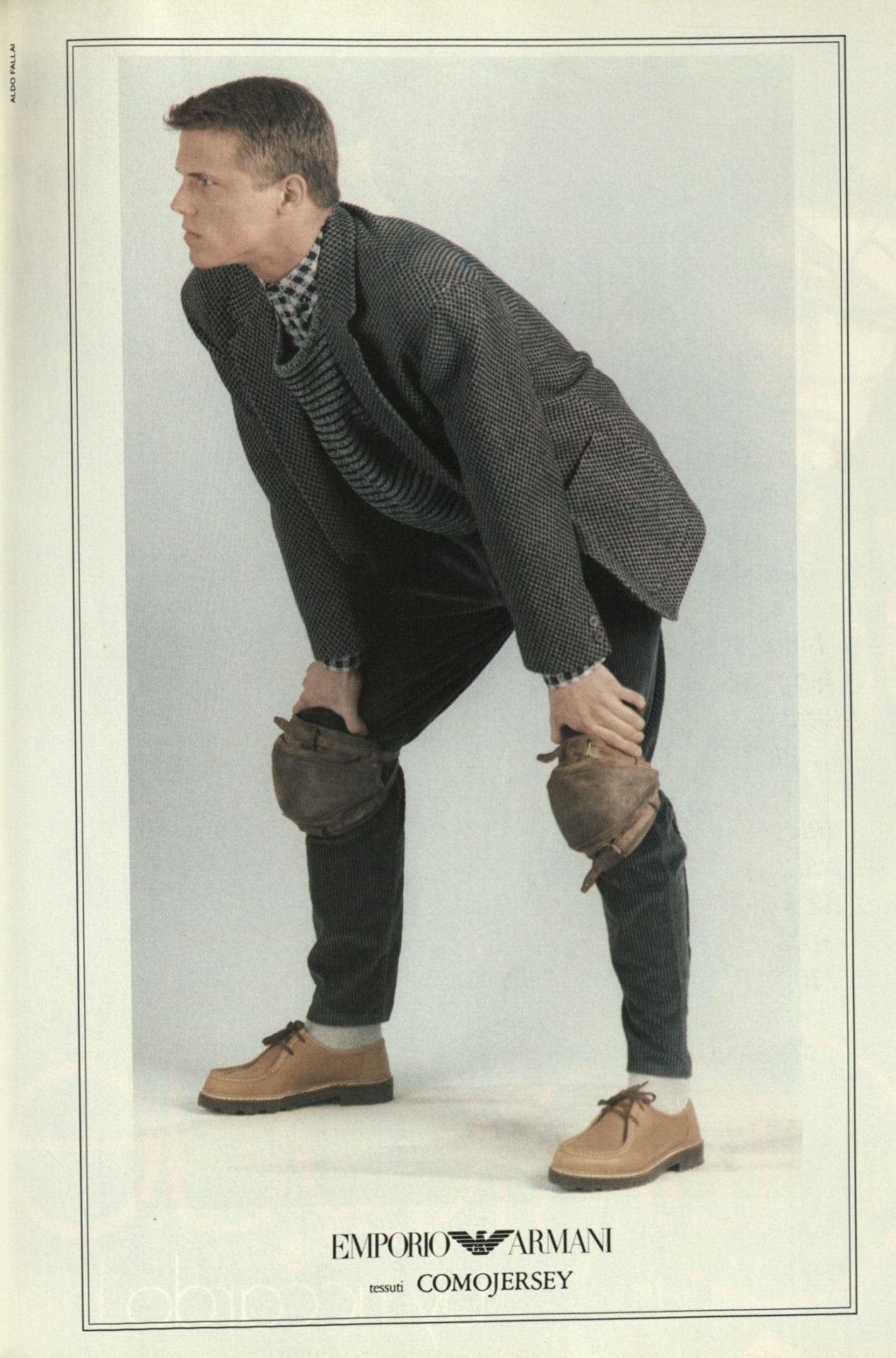

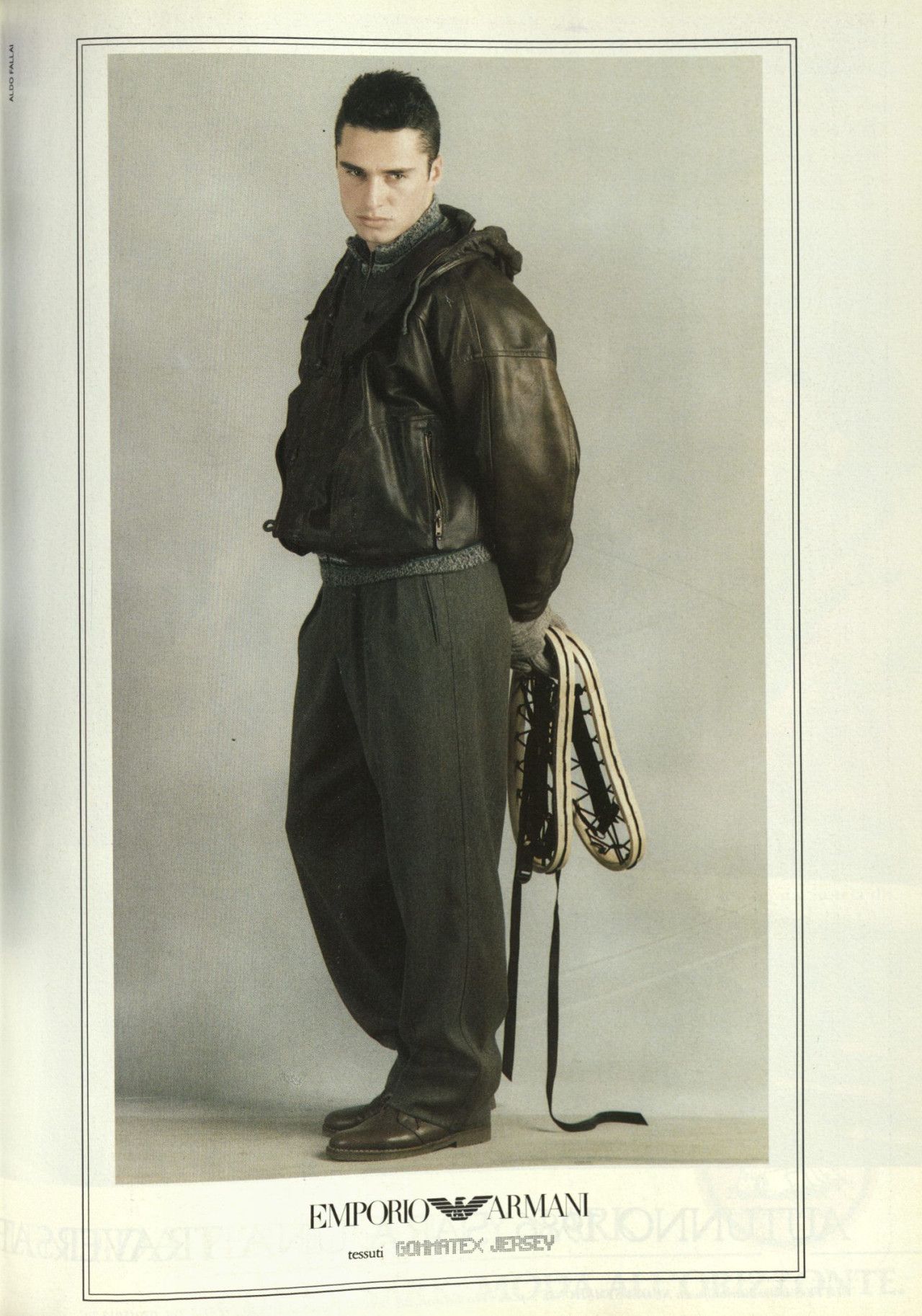

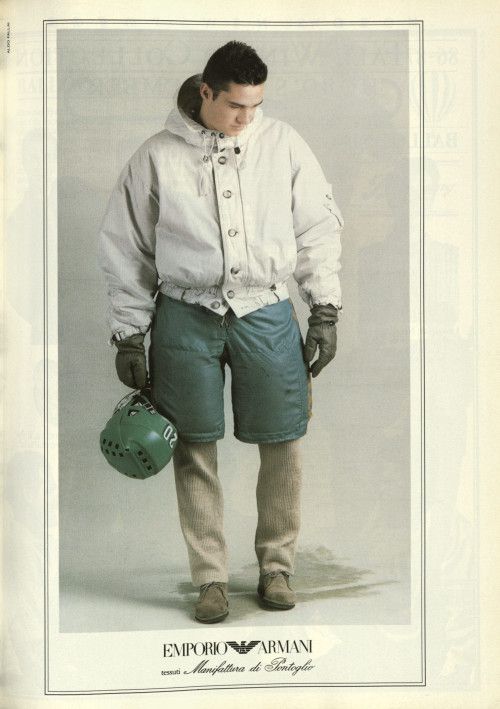

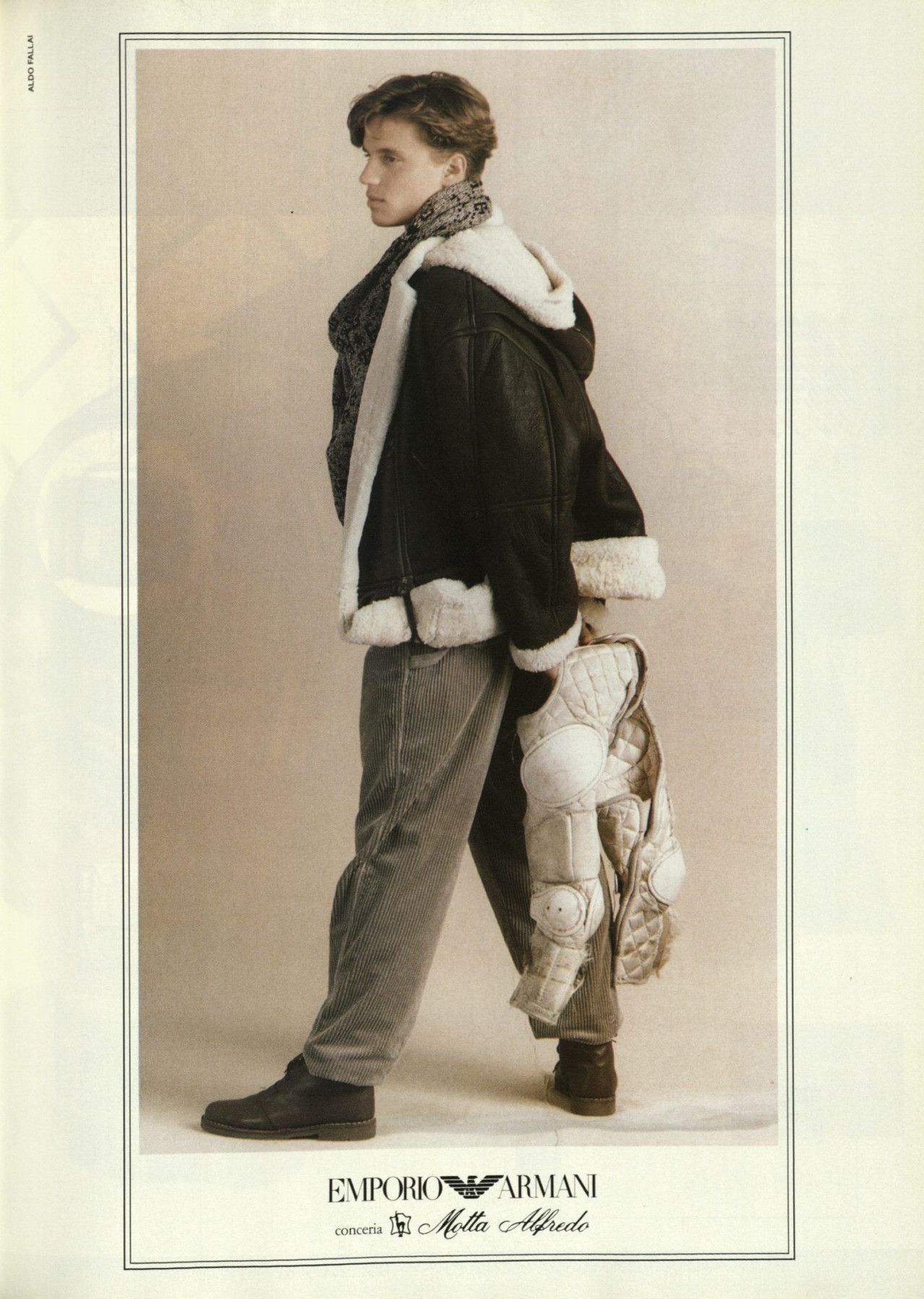

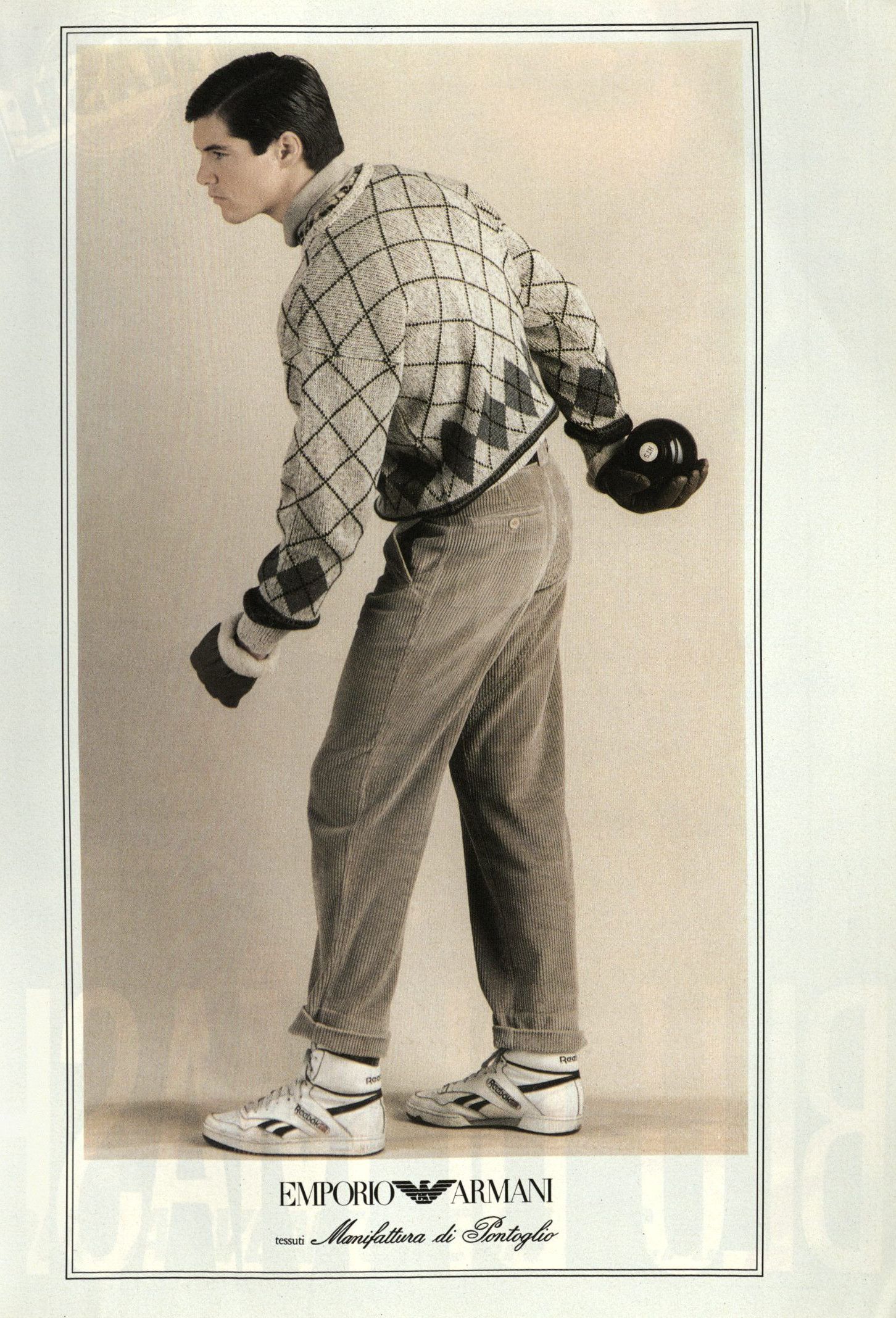

The most representative shooting of the potential of Emporio dates back to 1986, it was signed by Dellai. Unlike most campaigns, it was in color, and styling included a very eclectic mix of garments and textures paired with leather knee pads, snowshoes, hockey clubs and helmets combined with soft oversized checkered sweaters, velvet pants, suede wallabies and, in the most beautiful shot, a white coat with a rounded sillhouette, combined with green quilted shorts worn over velvet trousers and gray lace-ups – a combination of fabrics, volumes and proportions that seems to come out of a campaign by Aimé Leon Dore shot the day before yesterday and which instead is just under forty years old. That photo is emblematic of the absolute classicism of an aesthetic that still makes those thick and draped sweaters, those checkered blazers, those comfortable pants still seem completely desirable – all produced in collaboration with historical manufacturers such as Comojersey, Manifattura di Pontoglio, the Motta Alfredo tannery and so on.

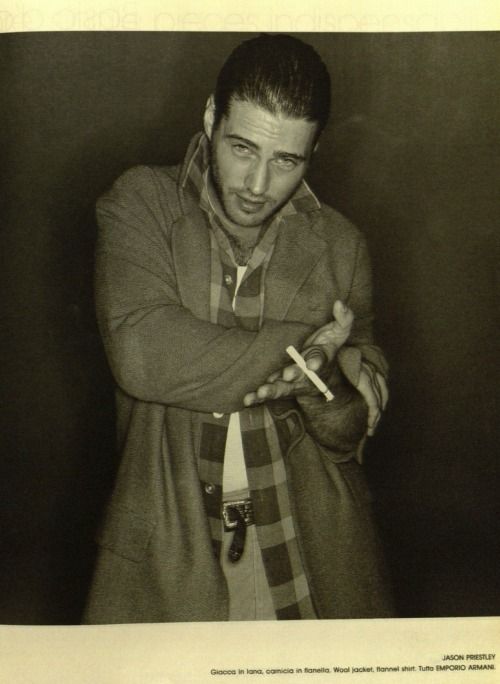

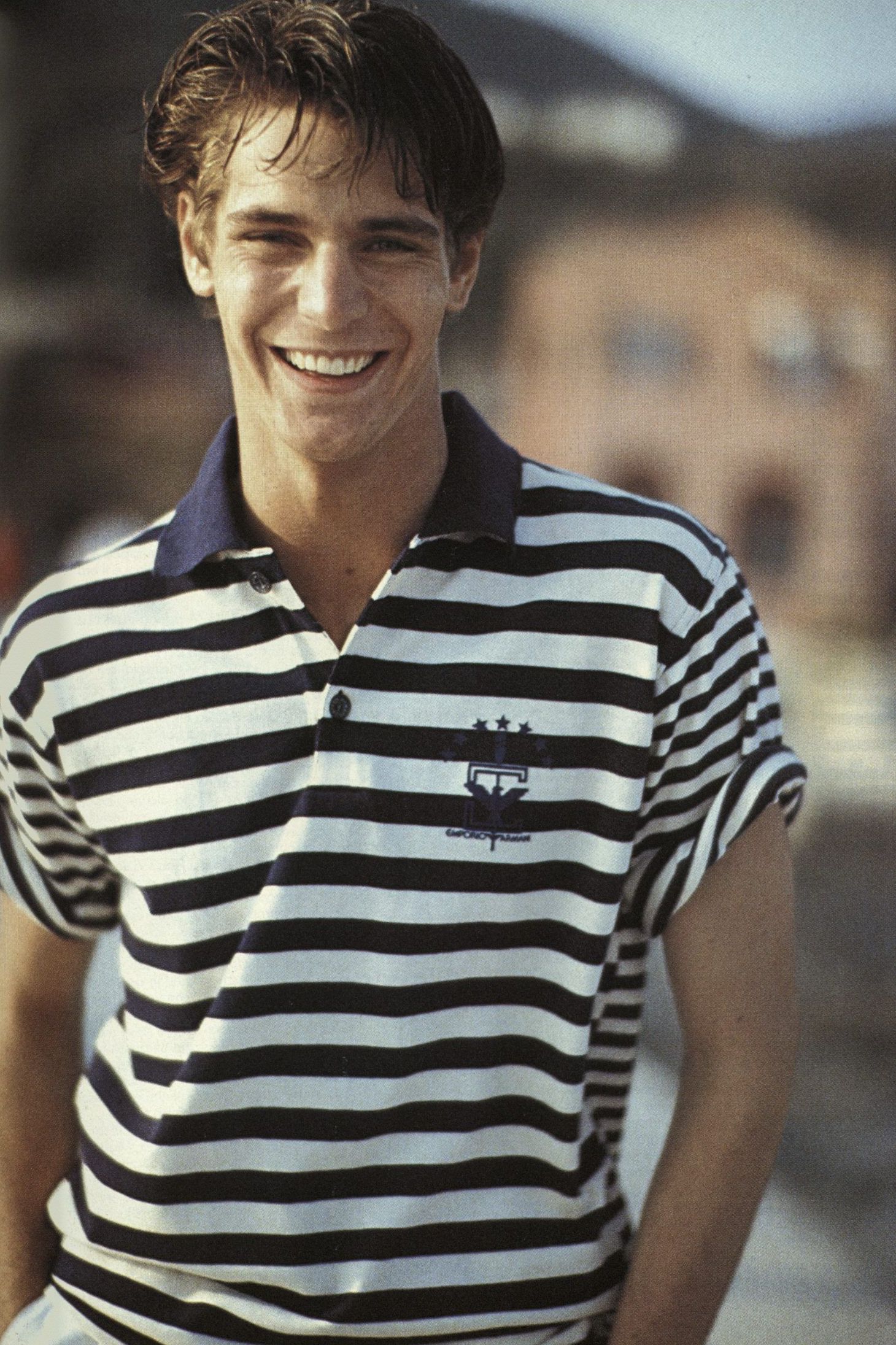

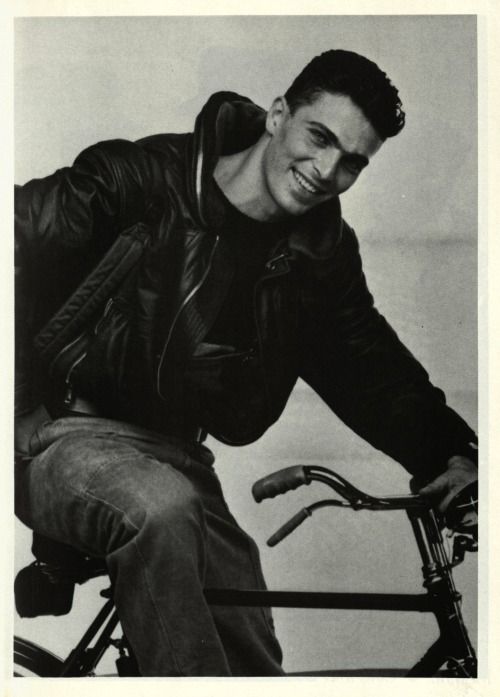

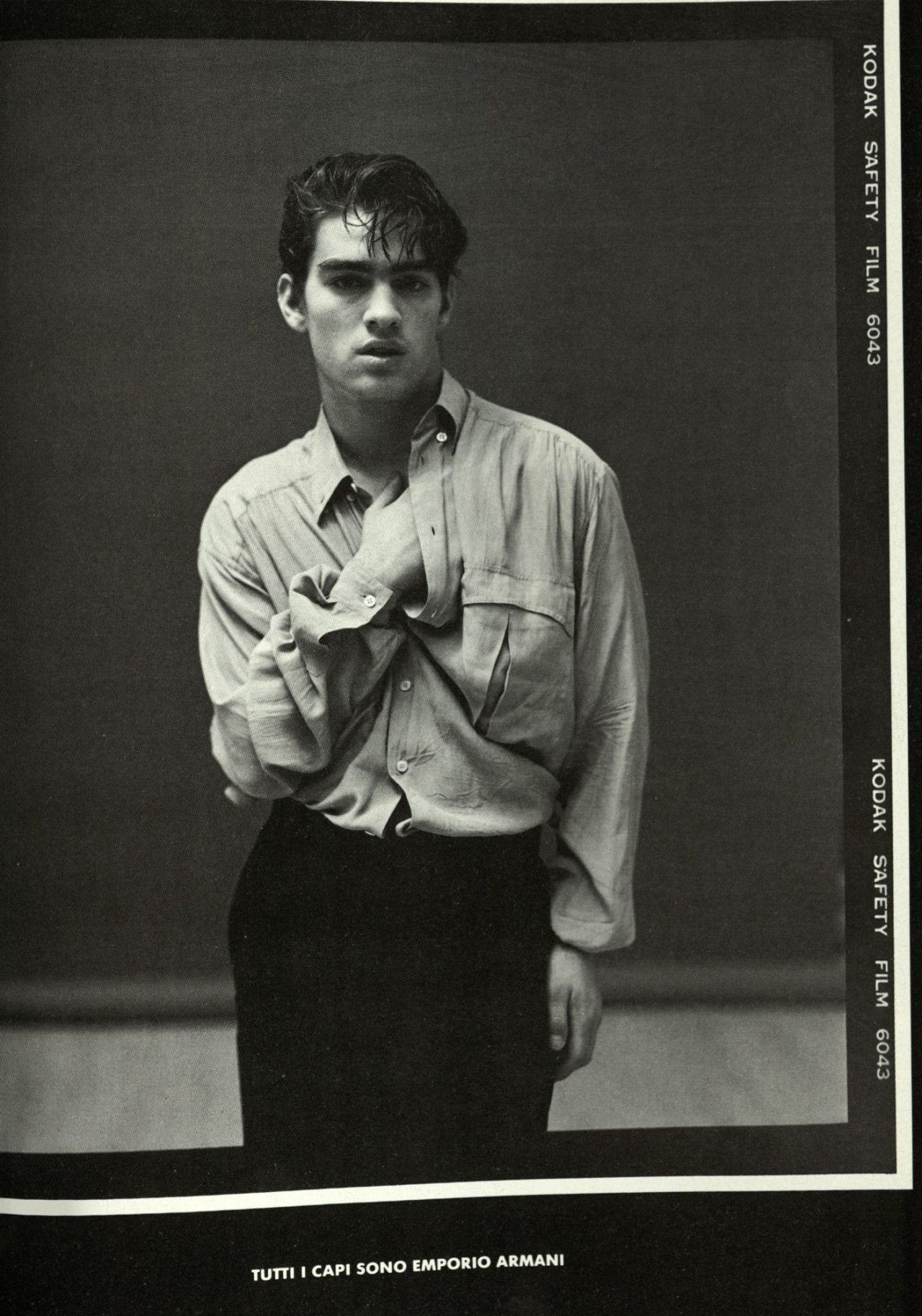

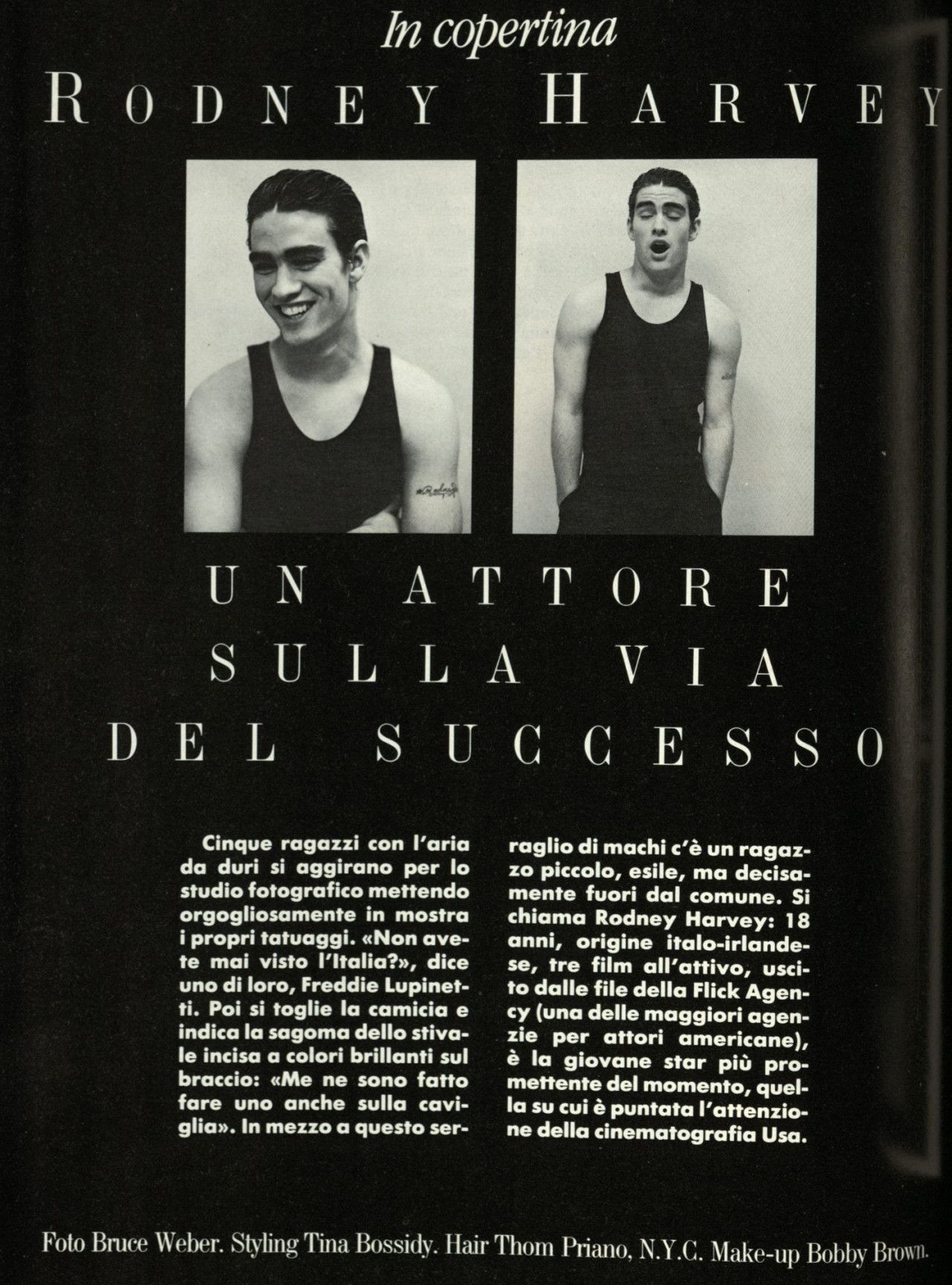

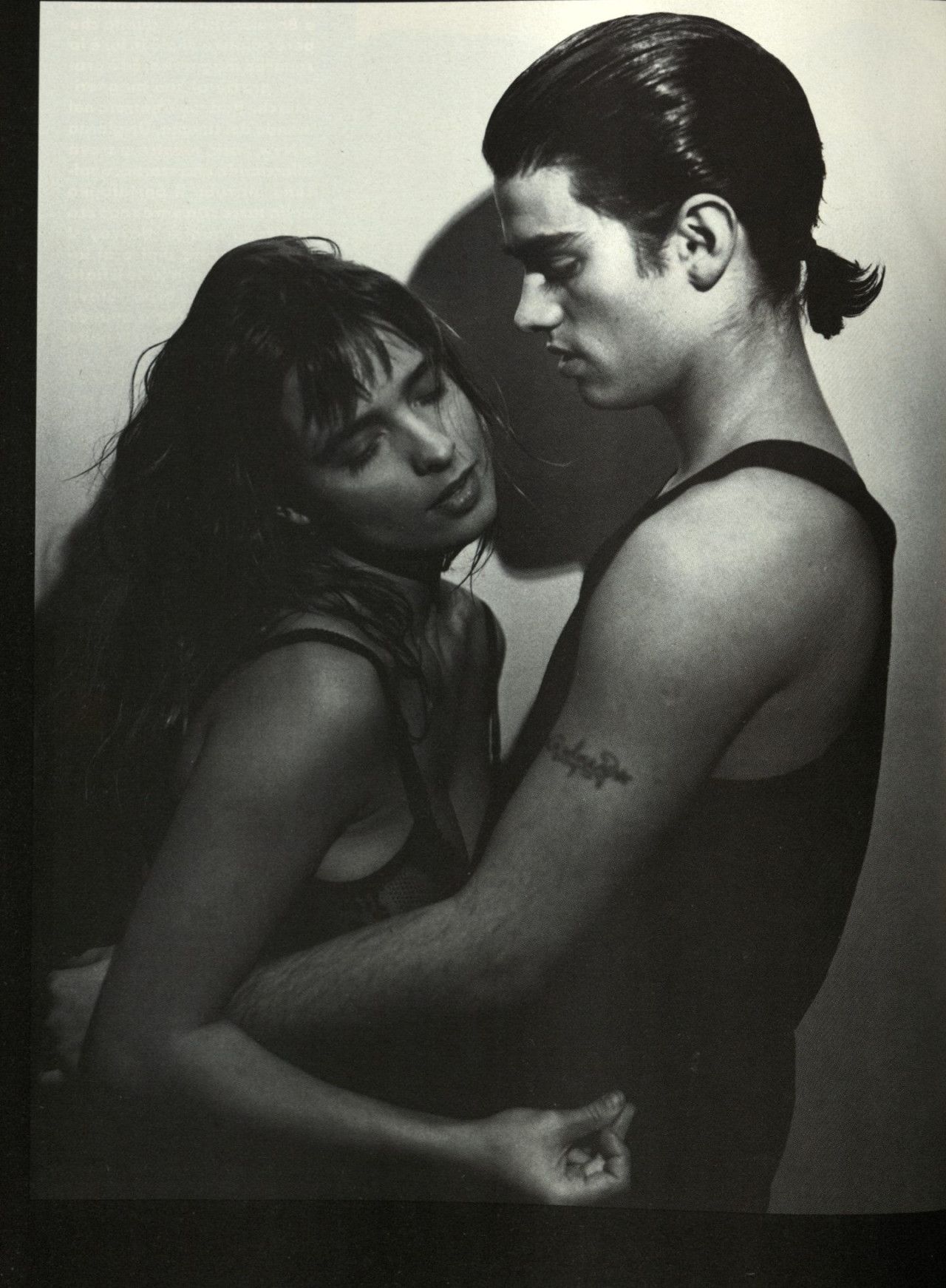

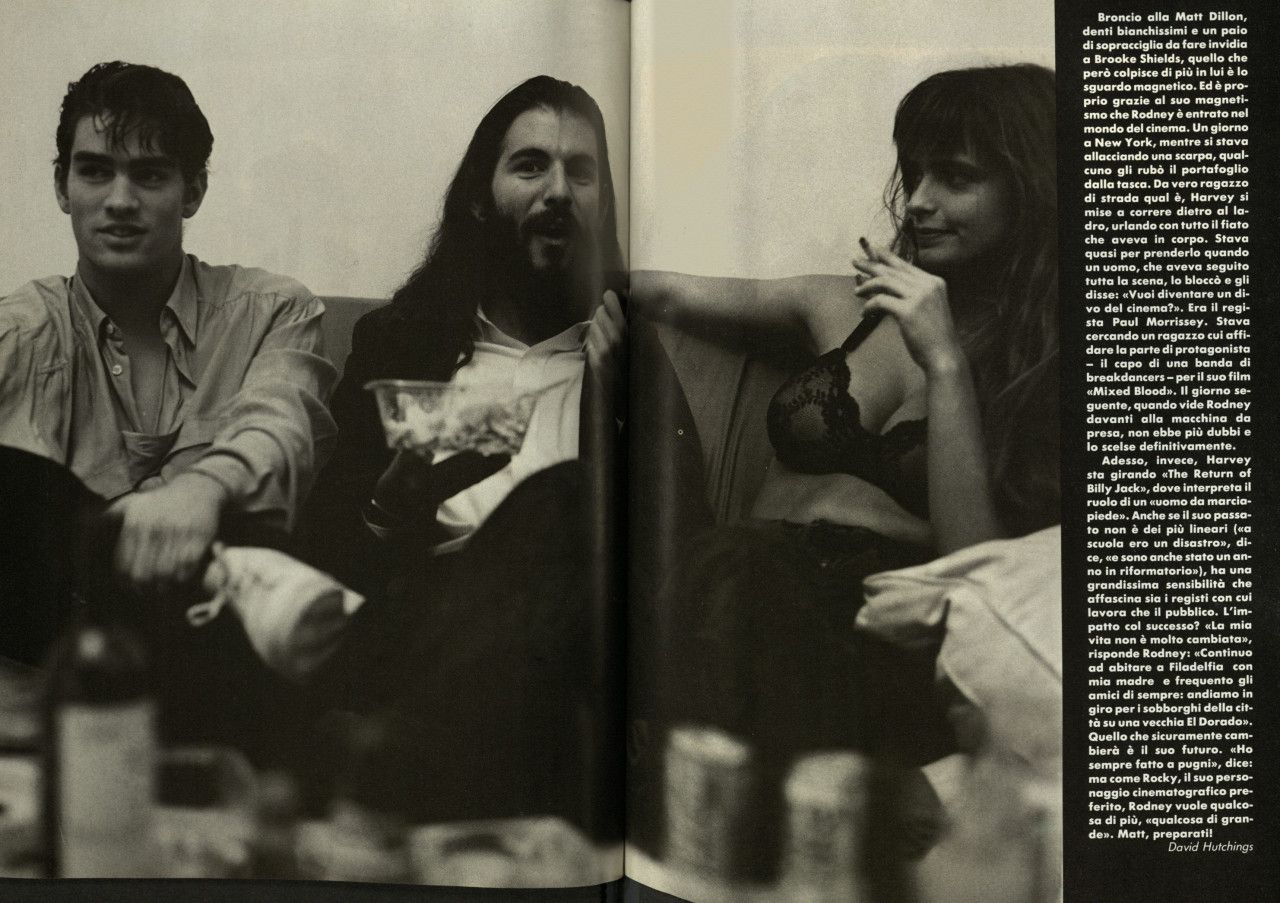

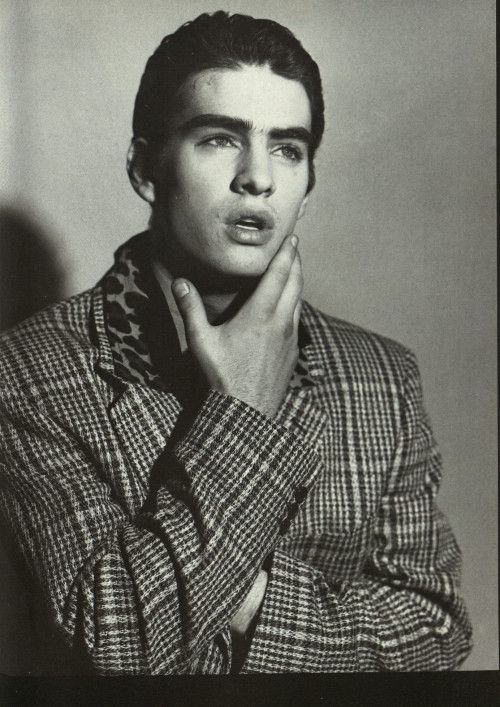

Strange but true, when the magazine Per Lui, a member of the Vogue family, published a report dedicated to the eighteen-year-old teen idol Rodney Harvey, the stylist dressed him in Emporio Armani from head to toe – testifying to an edginess that distinguished the brand and its very strong recognizability, even in the face of a complete lack of logos.

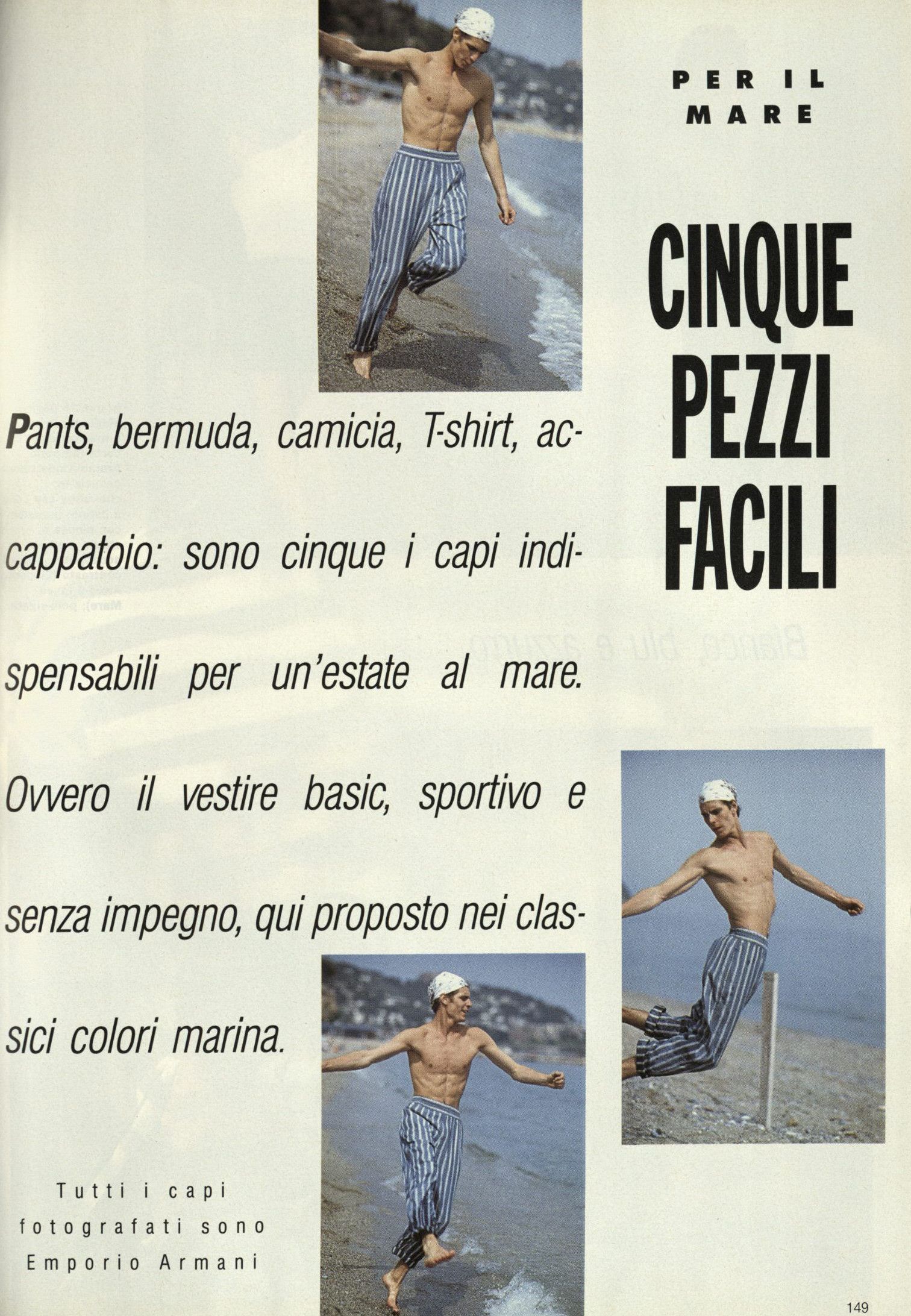

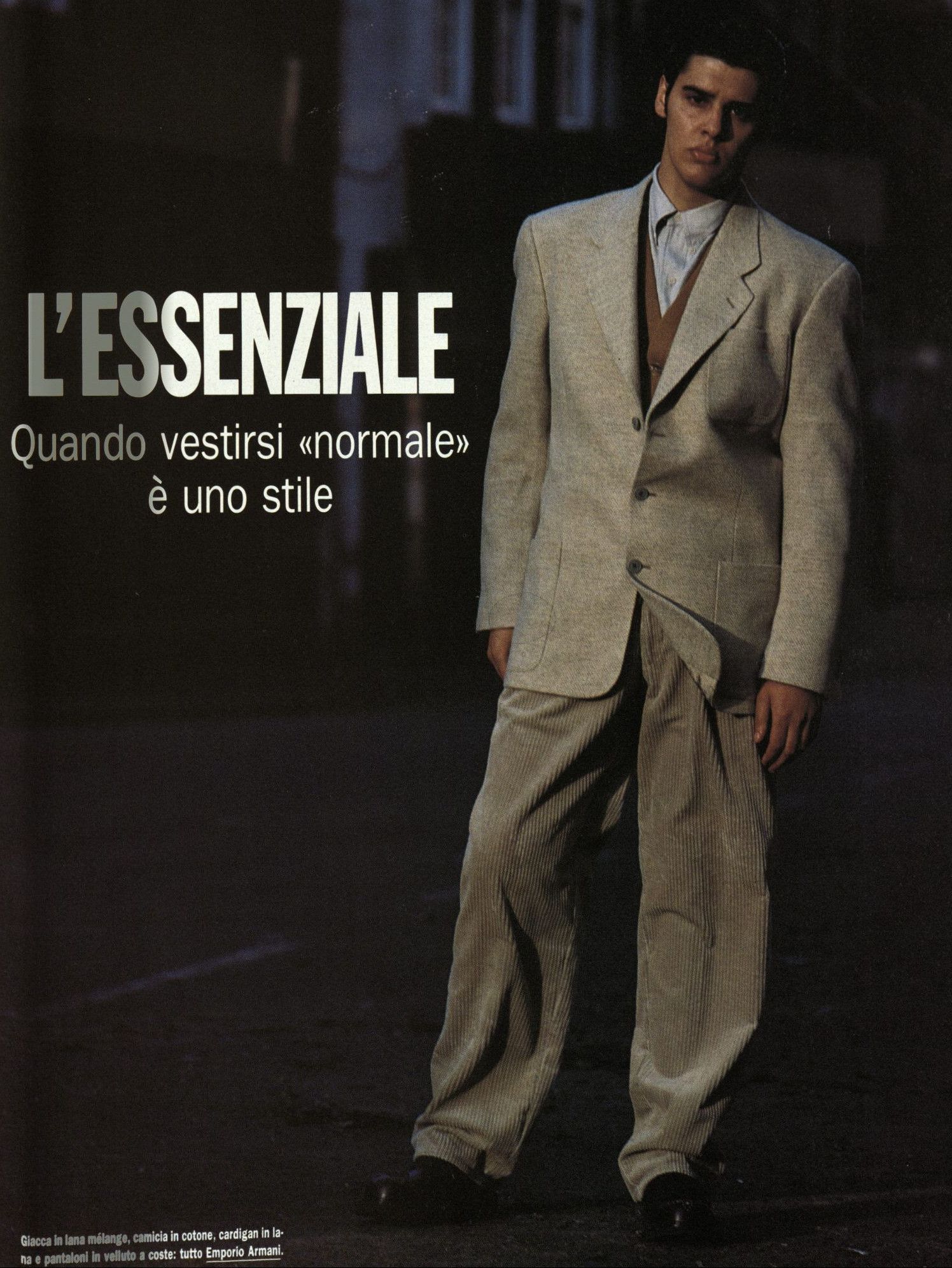

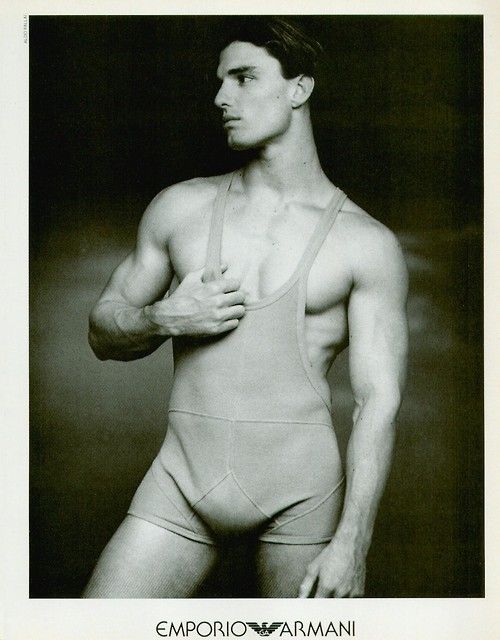

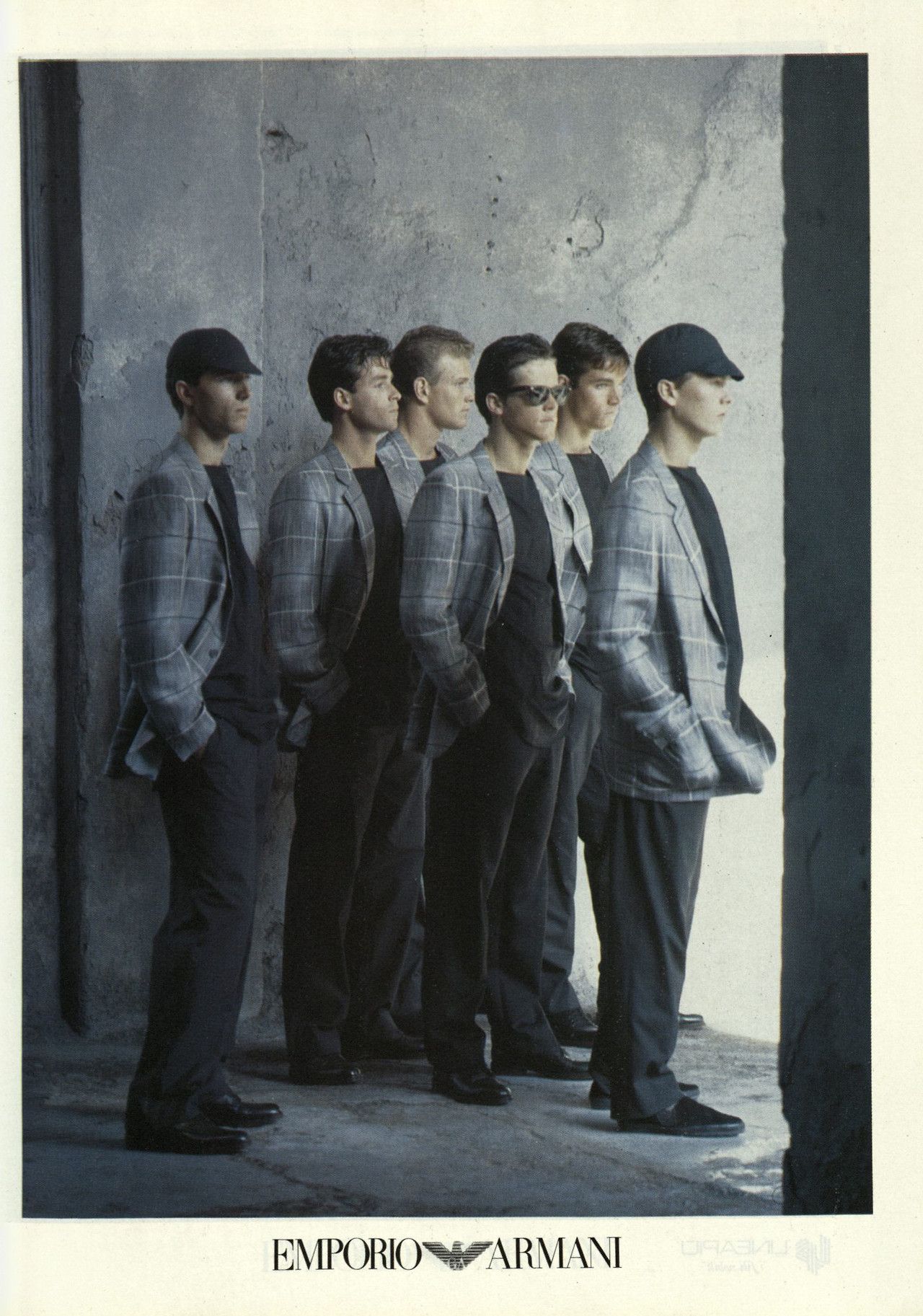

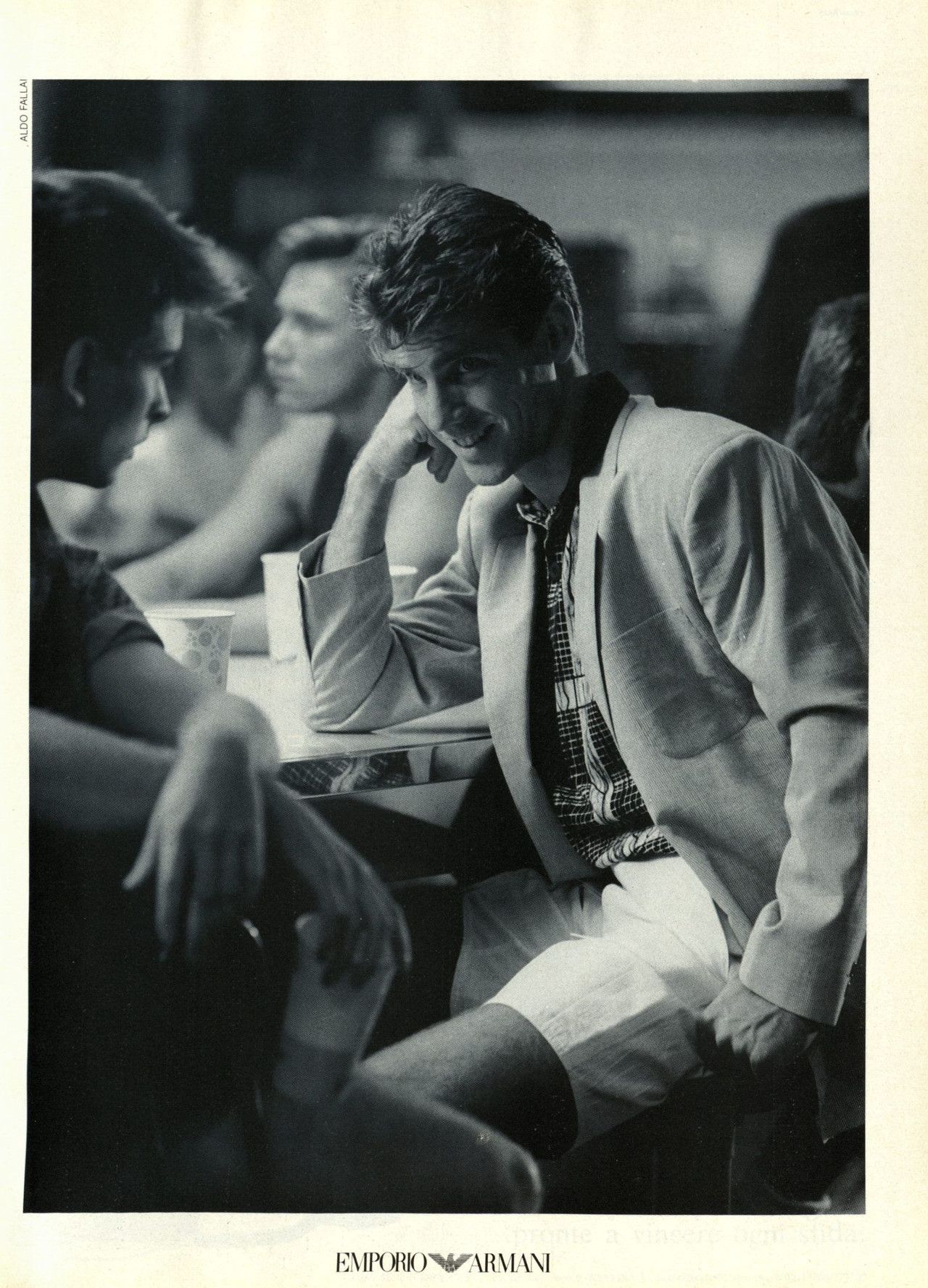

Talking with System Magazine in April 2014, Armani remembered Emporio Aldo Fallai's pictures: «The models had to be natural, neat, expressive. I wanted faces that could suggest the ability to think and that demonstrated fullness of character. For many years garments had been made with stiff fabrics that rigidly boxed up the body. I preferred naturalness, nonchalance, small flaws, and that’s why I chose soft fabrics and materials which were able to caress the body as it was never done before during the industrial revolution. It was a new sensibility that went beyond the stereotype of muscle men because it revealed a sense of rigour and precision that didn’t affect men’s sensuality». All very true words that however cannot fully explain the visual richness of those looks, whose range was vast and included both tailoring suits and jeans, workwear but above all sportswear – and all this in an era in which the Zarification of fashion brands had not yet happened and the idea of a full look dedicated to young people did not really exist. Going to analyze the many Emporio campaigns of the time, for example, we notice many aspects to the trousers – light-hearted and very relaxed response to the sartorial hems of the 60s and 70s suits and symbol of a generation that was beginning to reinterpret the wardrobe of its fathers.

For the avoidance of doubt, however, it must be said that many of those looks still appear dated, very 80s but still never know old, precisely because of that mix of sartorial rigour and soft lines that today are almost avant-garde. Some jackets from a 1983 campaign would not disfigure at all inside a modern collection of Bottega Veneta with their cropped waists, long sleeves and cargo pockets. A type of relaxed look that was lost during the minimalistic and sensual 90s, an era during which the young preppy disappeared replaced by a sexier formality, by an increasingly loud and technical sportswear and the excessive world of the 80s (which Armani had represented in the opulent drapery of his trousers) was forgotten.

If even today international travelers who land at Linate are welcomed by the monumental sign that recites the name of the brand and if the brand itself belongs to that narrow circle of diffusion lines that survived the 90s and early 2000s, the long existence of minor lines such as Armani Jeans and EA7, which lasted until 2018, made it lose the luxury aura of the first collections by diluting the prestigiousness of Armani's eagle in a cascade of branded products that have invaded every corner of the Italian province for years. Today the aesthetics of the brand stands on a more conventional and trend-oriented luxury, certainly in line with the times and with the market but also much less recognizable and distinctive, when instead its DNA is something that opinion leaders actively seek and desire. This perceptive change has to do with the brand but also with its context: on the one hand, in fact, there is no longer a distinctive aesthetic of Emporio Armani and the brand has lost that youthful freshness that distinguished it; on the other hand, the market has been saturated with high basics much more accessible as well as other younger fashion brands with a more pronounced identity, with the soft aesthetic of Dellai's 80s campaigns which, abandoned by Emporio, has been revived with great success, for example, by Teddy Santis in his campaigns for Aimé Leon Dore, by Justin Saunders in his moodboards for @jjjjound or by brands such as Sporty & Rich.

It would be interesting to see, today, in the face of a remarkable economic and logistical growth compared to the 80s, Emporio reclaim its ownership of an aesthetic that in fact belongs to it by right as part of its history and its past and therefore much more authentic and sincere than the many other brands that today are riding this aesthetic. New consumers are looking for a story and Emporio Armani still has its own – and it's a lot. But if already the brand, on the occasion of its 40th anniversary, has begun to dust off its most classic style with a new campaign signed by Francesco Finizio, coinciding with an increase in the popularity of the brand in the world of vintage research, it is not excluded that even Emporio Armani may one day return to be the most famous name of the new Italian preppy.