Can you denounce a brand for cultural appropriation? We asked the lawyers of the Herbert Smith Freehills law firm in Milan

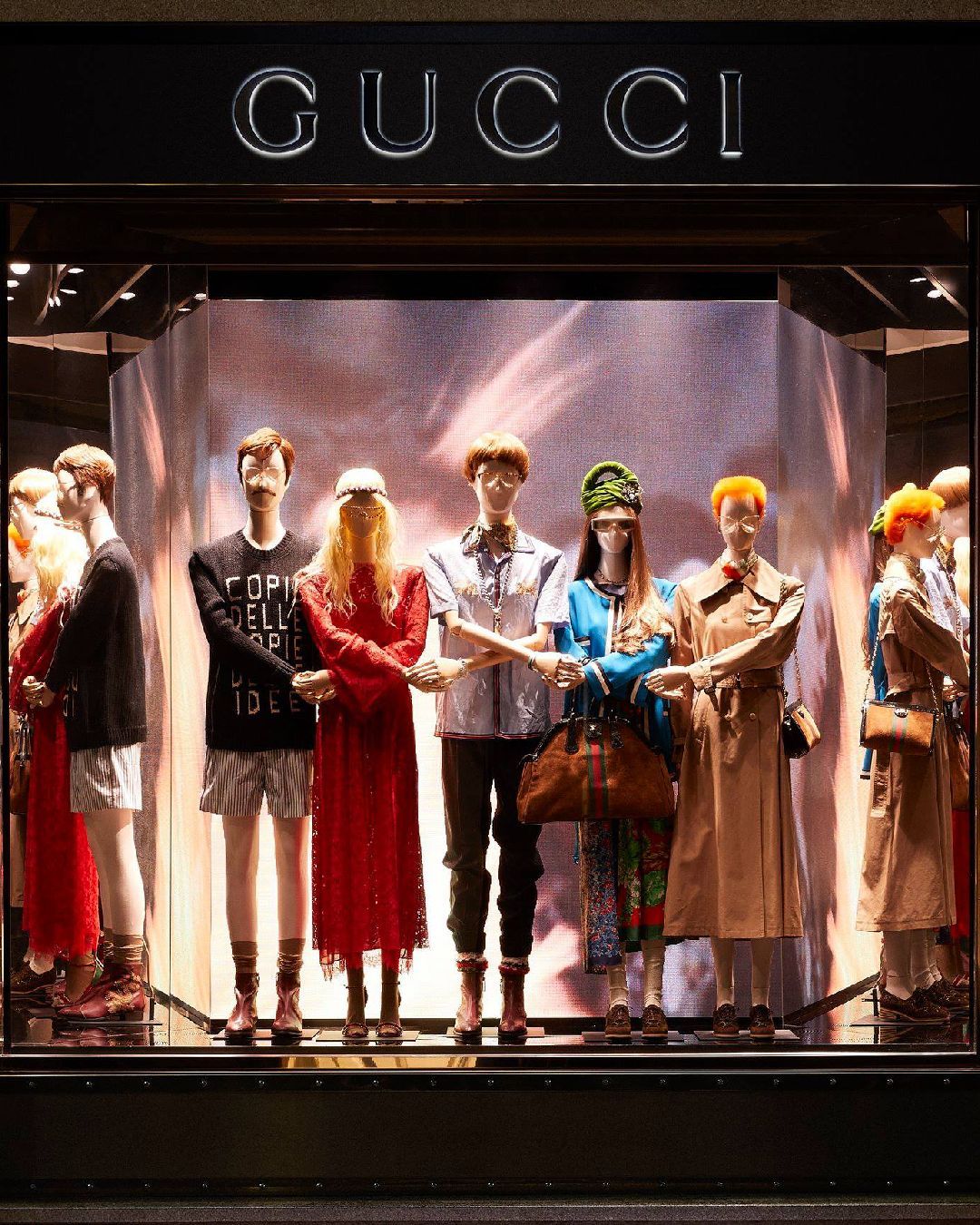

«The problem of cultural appropriation is twofold: on the one hand, designers subtract identifying elements of a culture or a specific community without requiring authorization [...] Secondly [...] traditional cultural expressions [...] are often misused», this is how Pietro Pouché e Giulia Maienza, lawyers of the Herbert Smith Freehills law firm in Milan have summarized the problem of cultural appropriation in fashion. An area that, legally speaking, is less gray than you think – but that still remains ambiguous enough to let episodes of appropriation occur at virtually every fashion season. One of the most recent involved Balenciaga, accused of having copied the saggy pants of the African American community, but also Gucci, which in 2018 had to withdraw from the market a turban that represented a religious garment for the Sikhs, while in 2020 it was Comme des Garçons Homme Plus who ended up under accusation for having made white models wear wigs with dreadlocks while Kim Kardashian was convinced by heavy online criticism to transform the name of the her line of shapewear from Kimono to Skims.

Brands and creatives change but the dynamic is always the same: «a member of a dominant culture that "appropriates" the traditional knowledge and the TCE [traditional cultural expressions, Ed.] belonging to a minority culture and uses them in a foreign context, without having obtained any authorization or involvement of the owner, without having any awareness of the meaning of the copied element, in order to obtain a commercial and economic advantage without paying any consideration». A power dynamic, therefore, that contrasts a strong to a weak and that, with the recent economic growth of fashion brands, becomes increasingly unbalanced in favor of the latter – but which is not always univocal. The culture of calling out, born substantially together with @diet_prada, has transformed social media and public opinion into "unofficial" weapons for minority cultures, also increasing consumer awareness. But it is clear that even the calling out has its limits: firstly because it does not increase the agency of minority cultures and secondly because it lacks the systematicity that the law could guarantee.

At this point the question arises spontaneously about the way in which a certain community can defend a cultural expression of its own but without real authors. According to HSF's lawyers, there is more than one way: the first is copyright that «would allow the indigenous people to be able to exploit their own creations, always be recognized as authors and prevent unauthorized exploitation and dissemination of others" with the possibility of "identifying not a single author, but a community»; another solution could be to «designate a specific authority to protect the rights to their own expressions of folklore», an option that in any case would not guarantee economic rights extended over time. Difficult to achieve, however, is the filing of registered trademarks, a very expensive operation, while an almost always effective method consists of certification marks and geographical indications. In the face of all these legal ambiguities «an attempt was made both to adapt existing intellectual property systems and to develop sui generis protection systems, designed and modelled ad hoc on the basis of the specific needs of traditional knowledge». The topic is in fact so dense with critical issues that vary on a case-by-case basis that both WIPO (the World Intellectual Property Organization) and UNESCO have set up a series of committees to find unambiguous legal solutions to the problems of cultural appropriation.

Fashion and IP: Facing accusations of cultural appropriation, the fashion industry is under pressure to be mindful when borrowing stylistic elements from other cultures. WIPO Magazine looked into the role IP can play in curbing this harmful practice: https://t.co/HFgEpIPxoD pic.twitter.com/lVqF3lstP9

— World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) (@WIPO) September 18, 2019

It is clear that the shortest way to solve the problem is to prevent it. Cultural sensitivity on the part of brands and creators is the main antidote to the problems of appropriation – but this does not mean that the creative side of the fashion industry cannot accommodate multiculturalism. «Just think of collaboration agreements with indigenous communities, the establishment of a constructive dialogue with local artisans on the creative process», explain HSF's lawyers – a whole series of recognition processes that transform appropriation into integration and, indeed, increase the intrinsic value of traditional knowledge applied to fashion. Transparency on inspirations and authorized collaboration with communities whose culture is to be integrated into fashion collections is basically a win-win: for brands, as it represents a tangible demonstration of inclusivity, and for communities whose artisans would obtain recognition, visibility and above all an economic return.

This type of inclusive policy on the creative side not only paves the way for multicultural collaborations, but could constitute a new frontier for fashion activism that would stop being (as it often is) only performative or separate from the authentic making of fashion and would instead result in absolutely concrete terms, with equally concrete advantages in terms of brand perception.