Why did Bottega Veneta chose Detroit for its new show? The Motor City was also the cradle of the techno wave that shaped the club culture worldwide

The next Bottega Veneta show, which will also be the first in a long time to be broadcast live-streaming, will have a fairly off-the-map location for a fashion show: Detroit.

The capital of Michigan has become in recent decades the symbol of the crisis of the post-war American dream starting from the 70s and 80s when it empties and turns into one of the most violent in the United States, a crisis that then culminates in the 90s and 00s when globalization dismantles the bases of Motor City, the titan of car industry. The city became the emblem of racial divisions and an urban landscape - of which the main icon has become Michigan Central Station - mindful of a glorious past and a gloomy present.

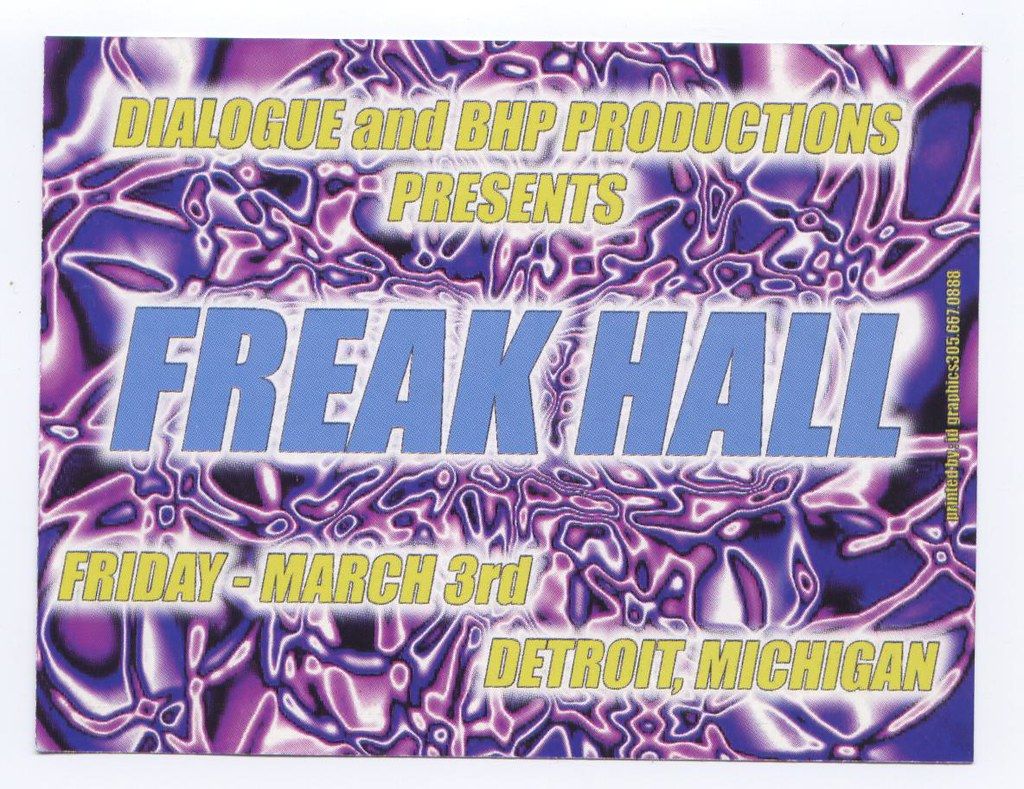

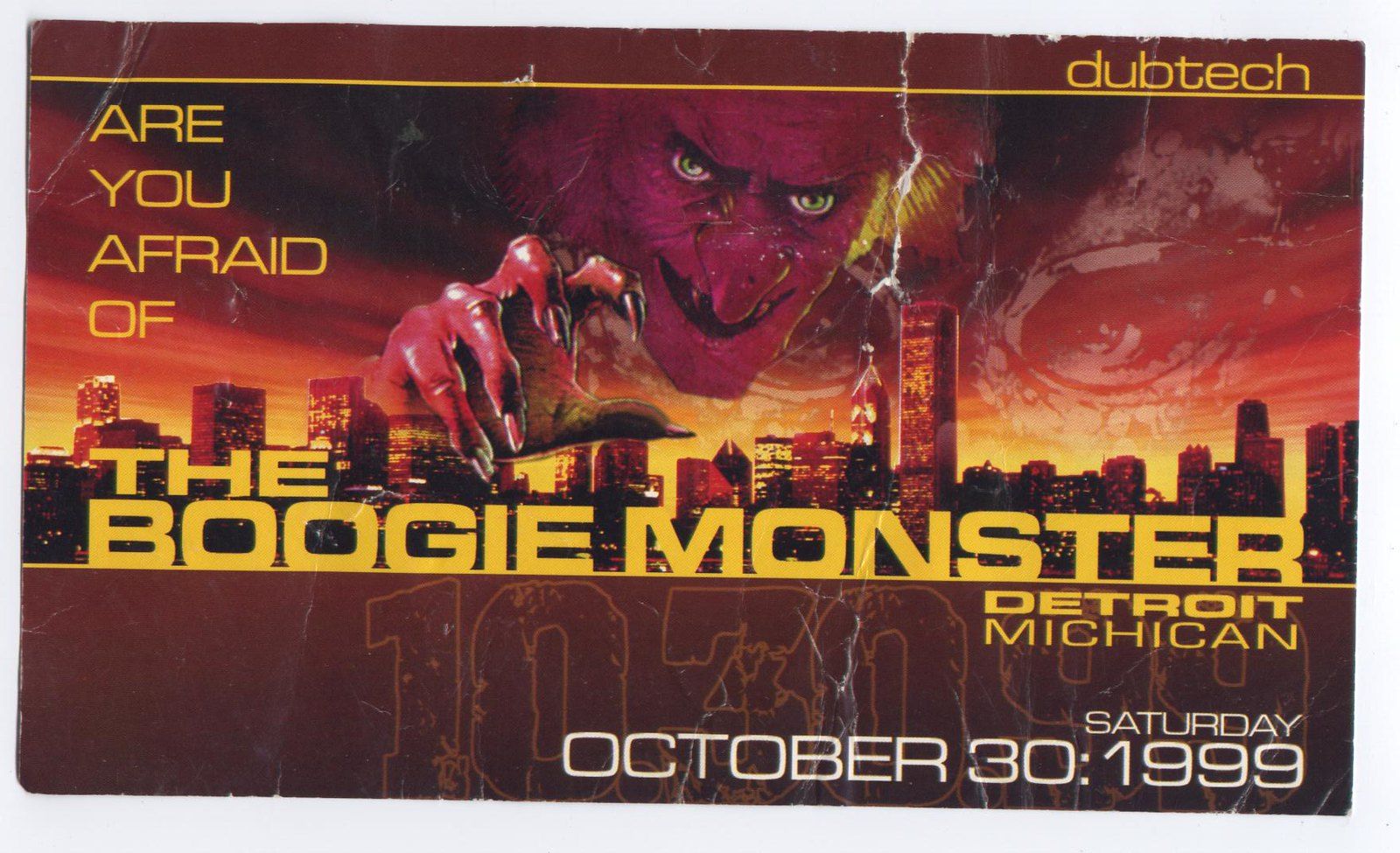

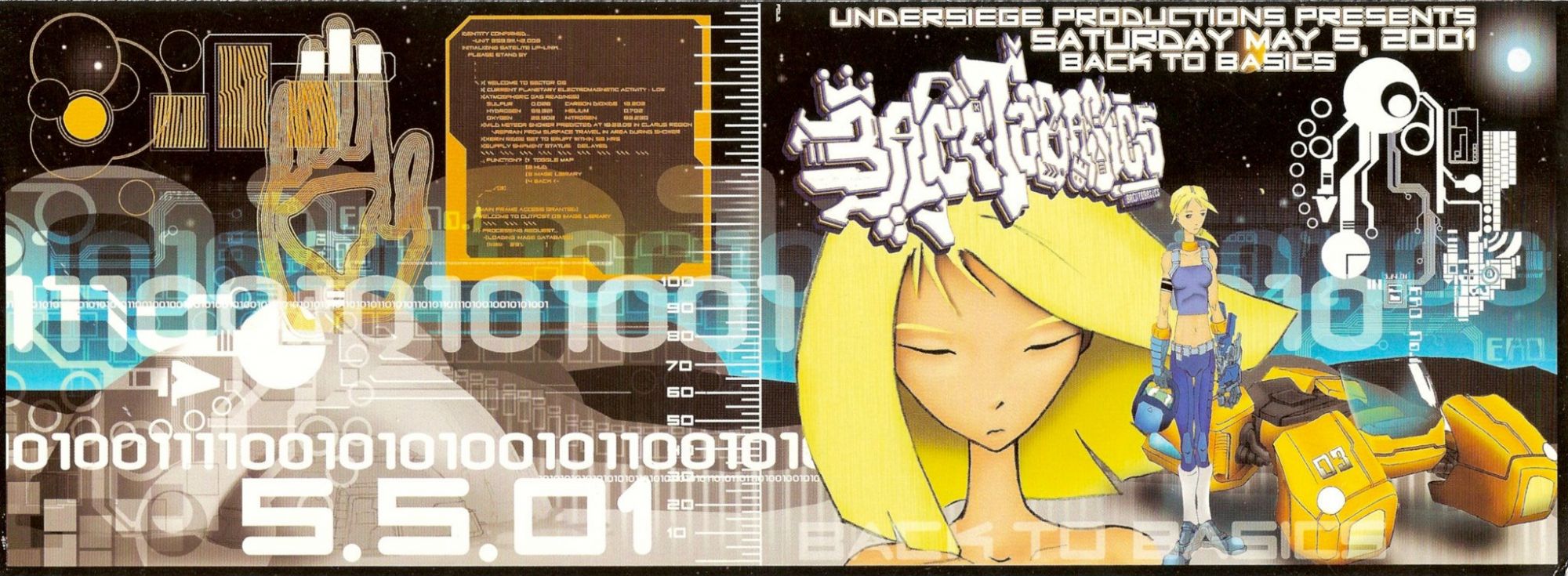

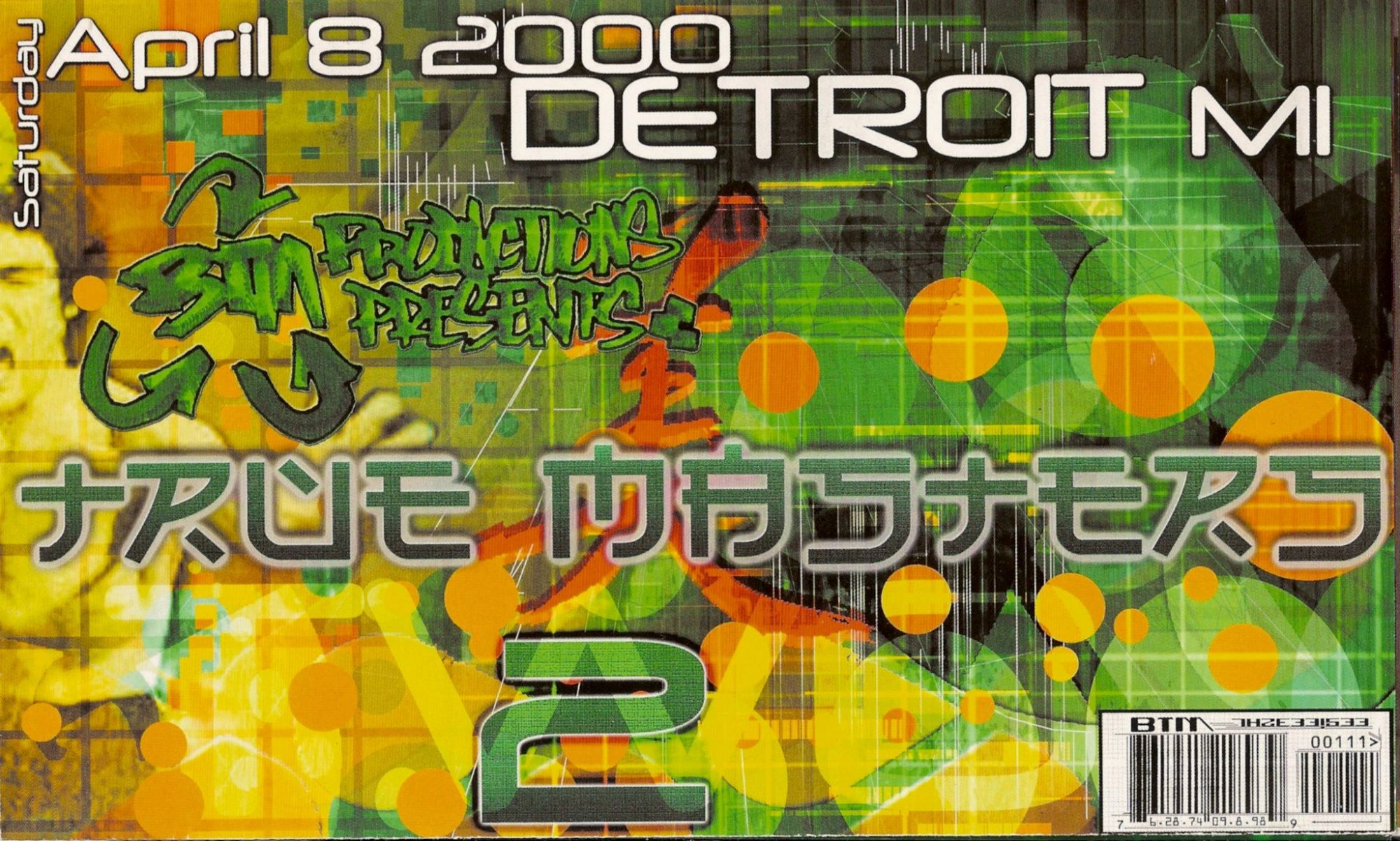

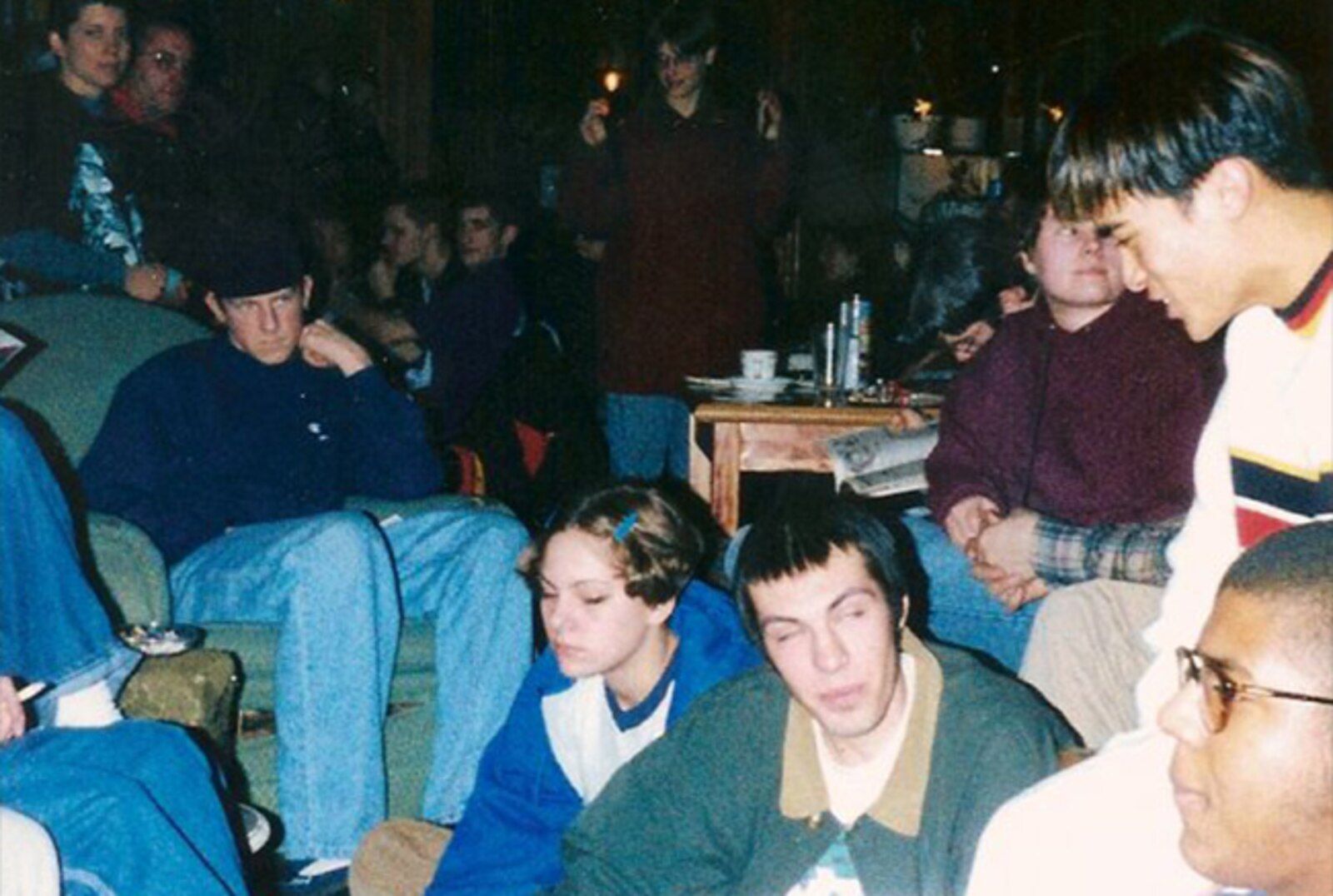

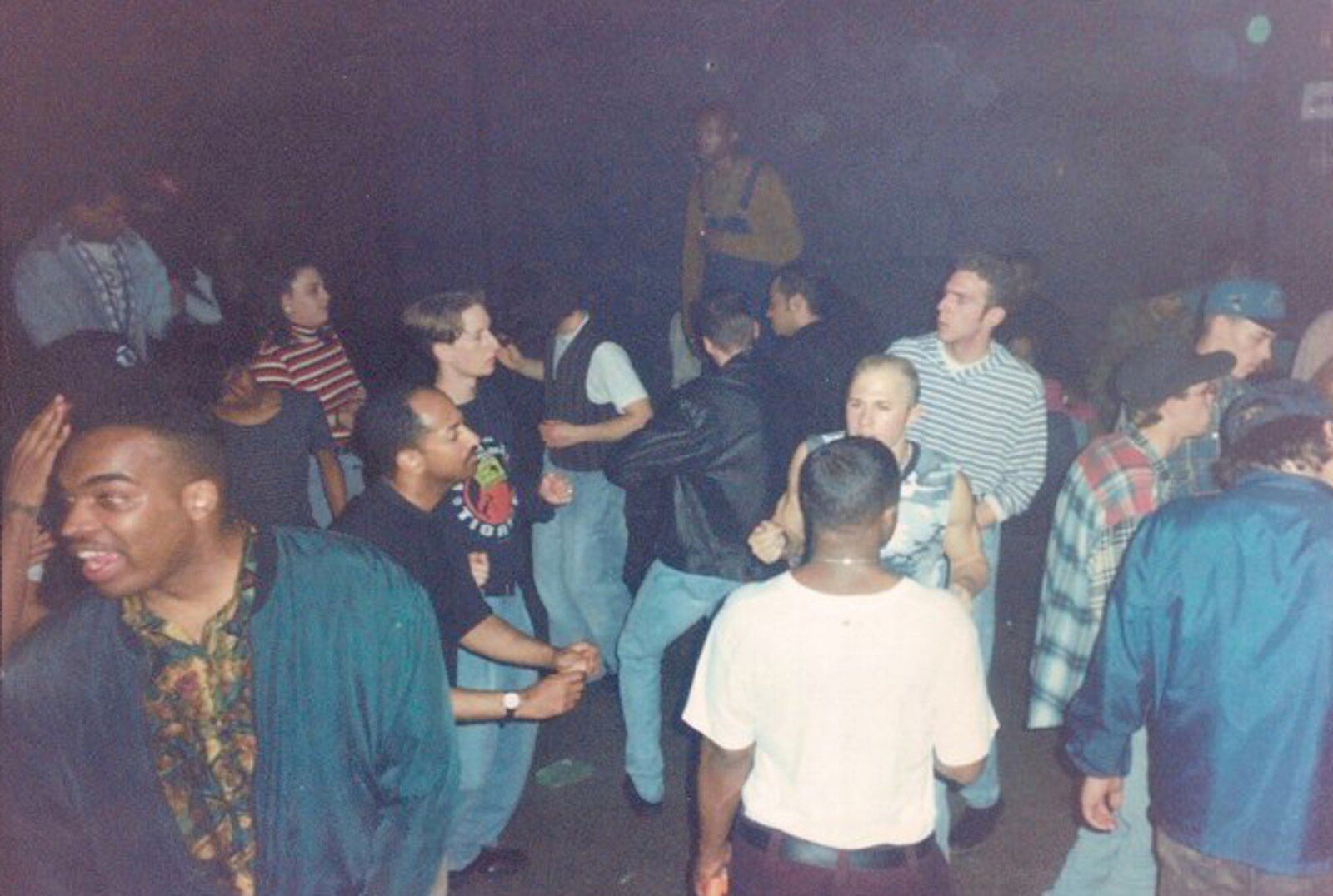

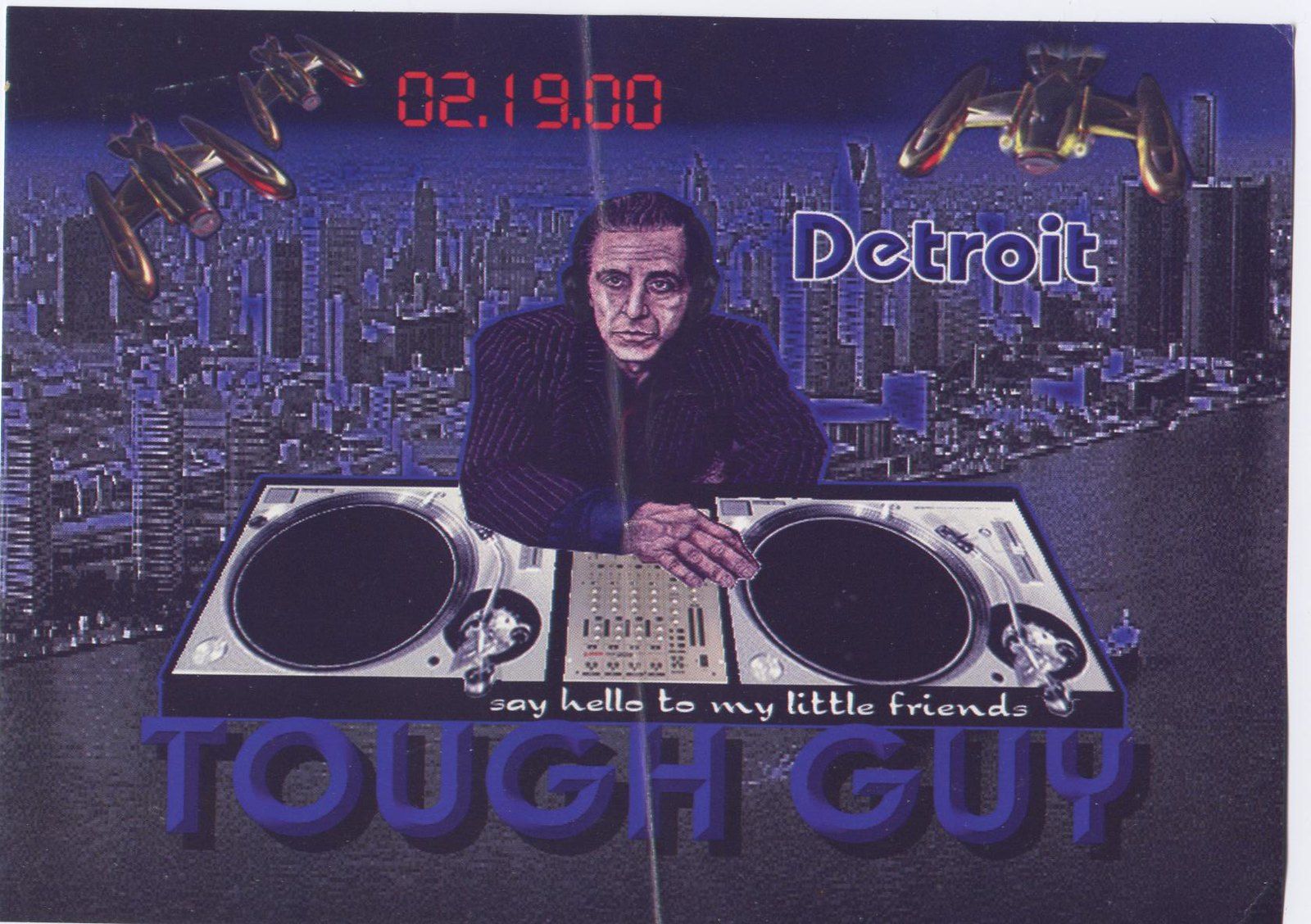

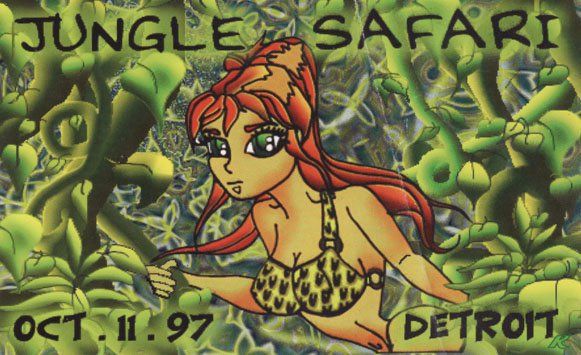

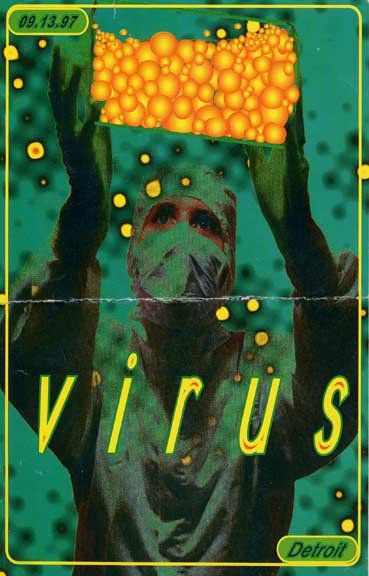

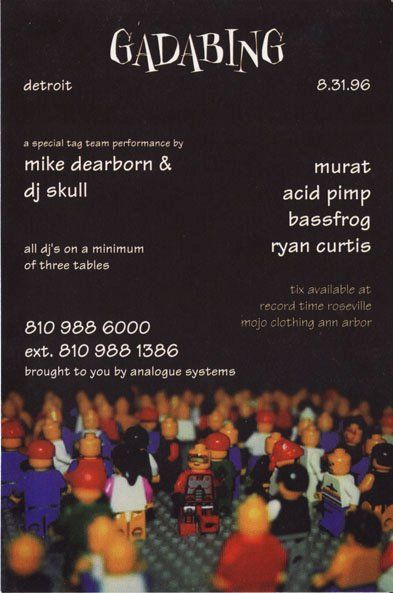

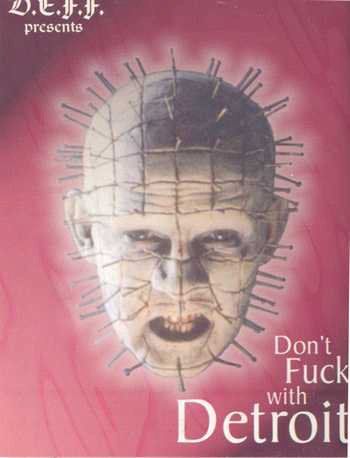

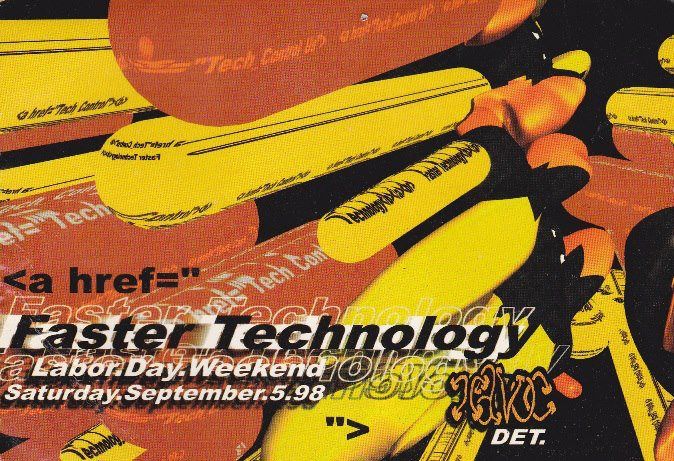

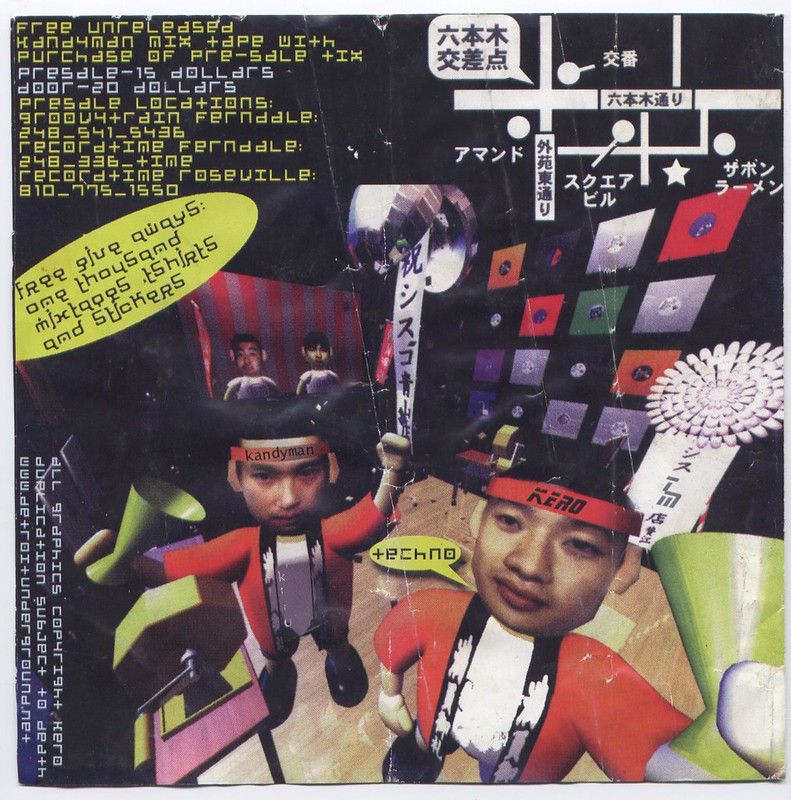

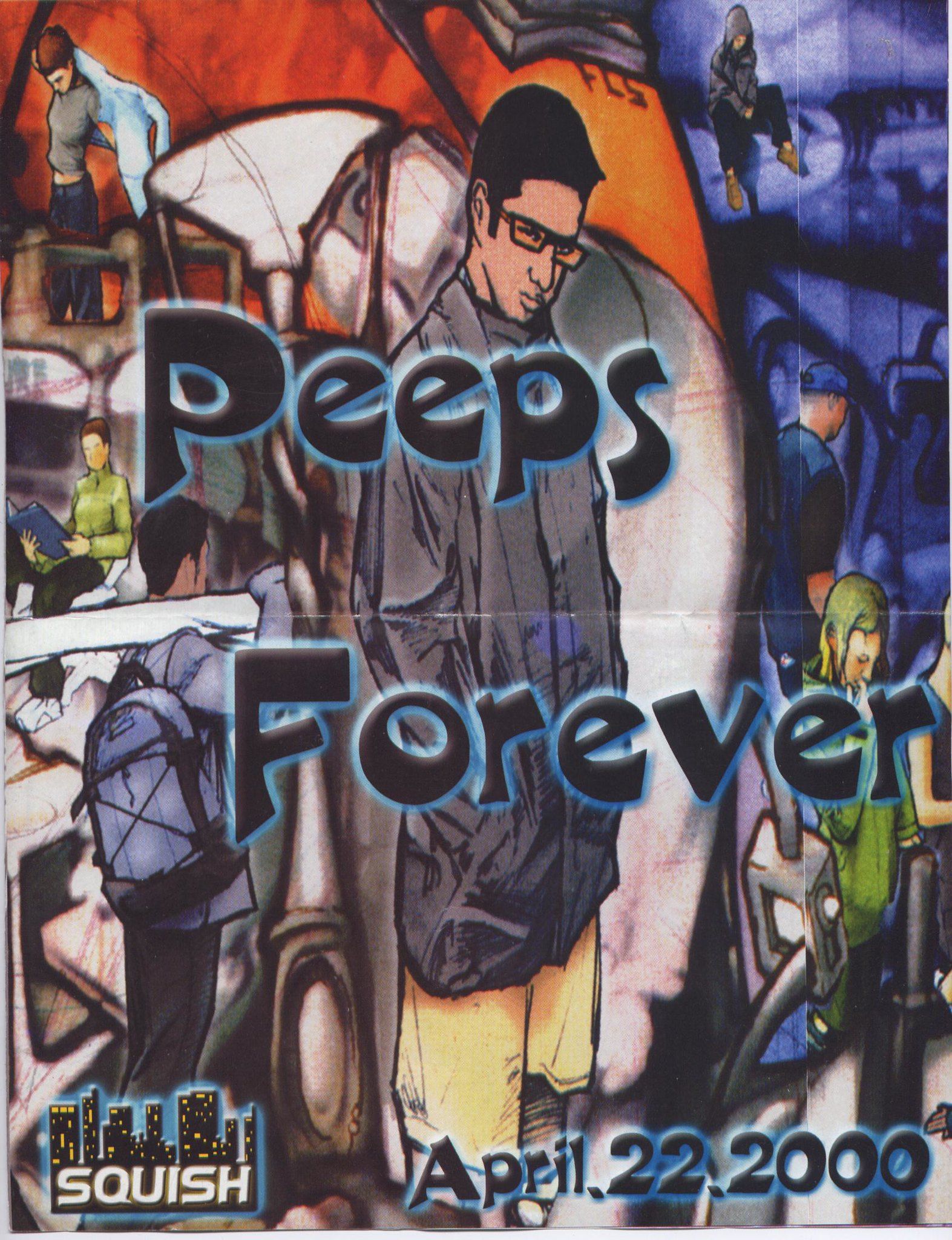

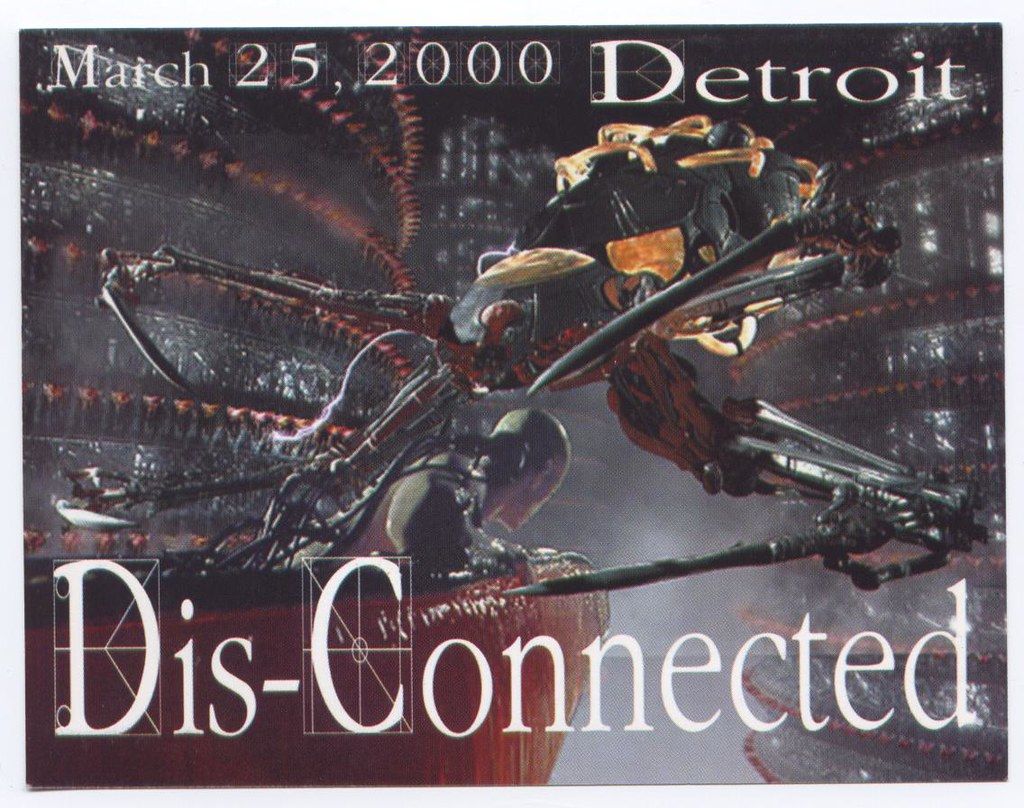

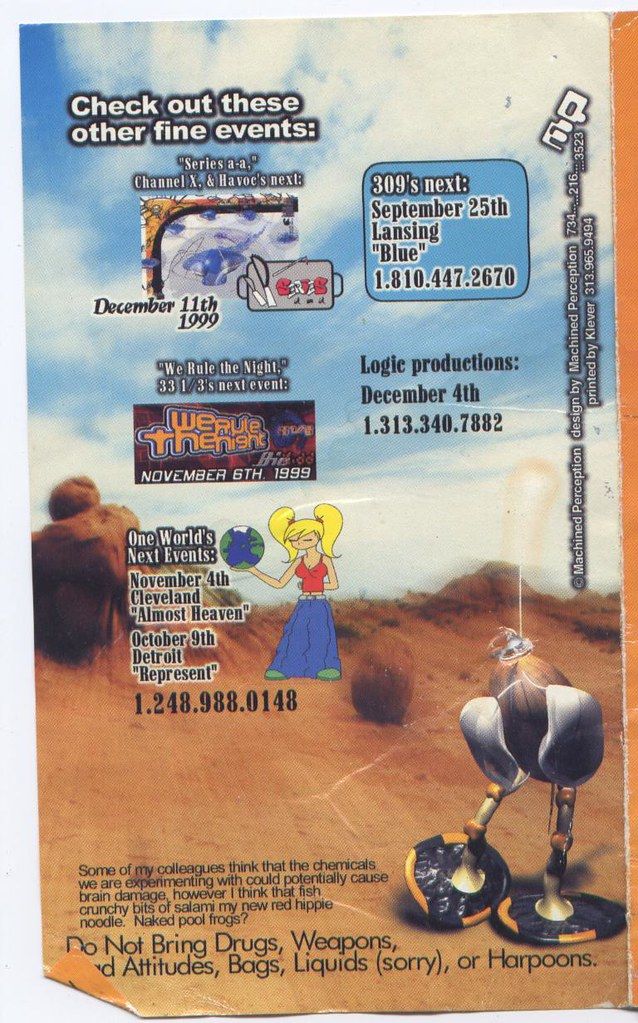

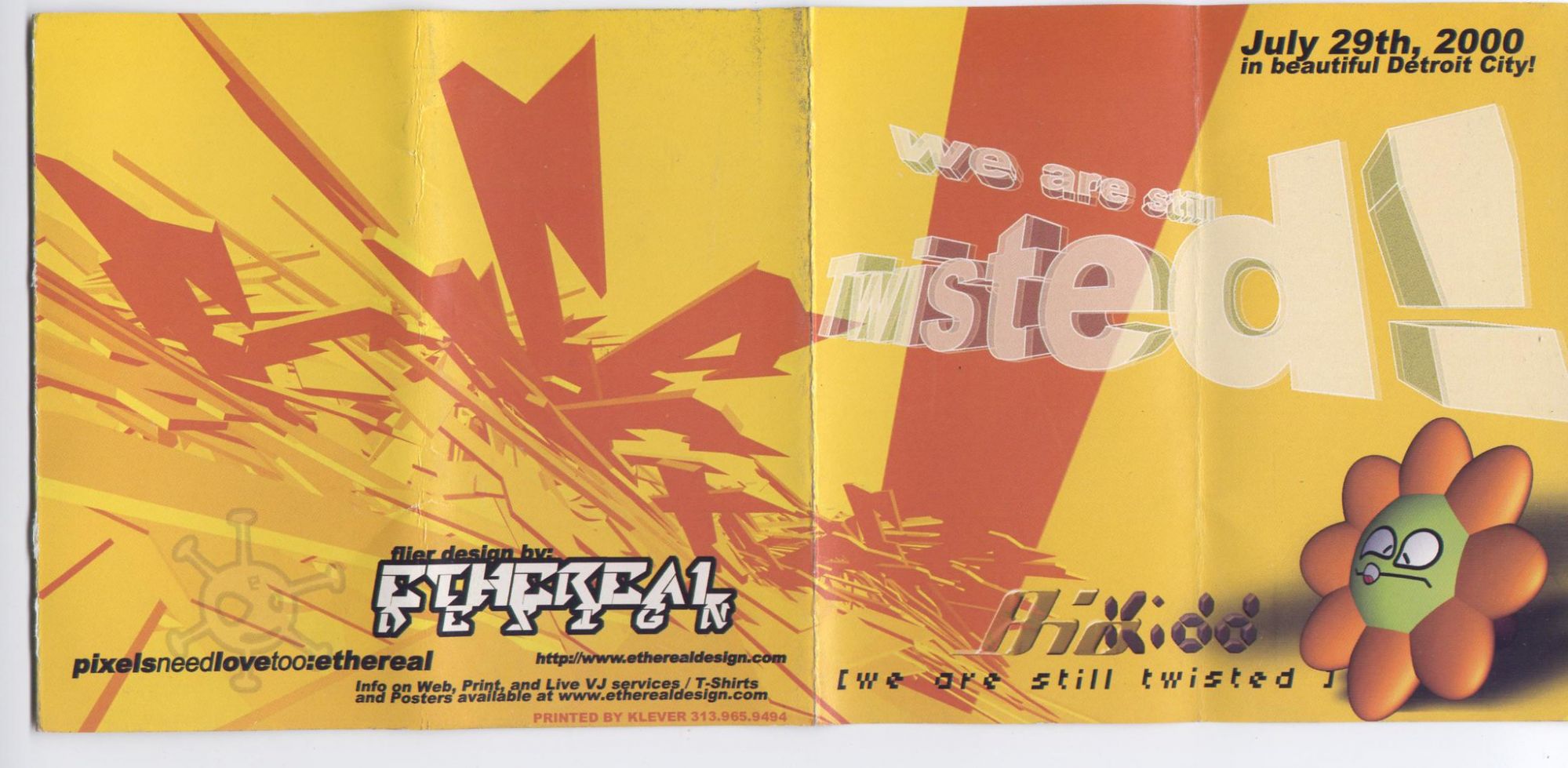

However, starting from the 80s those reinforced concrete skeletons offered the young people of the city the perfect habitat for a cultural revolution that from the center of the United States would have invested the whole world: techno music.

Detroit is in fact recognized as the cradle of techno music, a sound that reached its peak of popularity in the 00s thanks to DJs such as Richie Hawtin and Carl Cox, to which influence created the world of clubbing as we know it.

Daniel Lee's choice to set the Salon 03 show in Detroit is part of the wider celebration of the link between fashion and clubbing, in continuity with his latest show at the Berghain in Berlin, one of the temples of European clubbing. In addition to culture, Daniel Lee seems to perceive the importance of the place - of the club - as a creative scenario that - from Tokyo to Milan, passing through New York and Tbilisi - has shaped creative personalities such as Virgil Abloh, Hiroshi Fujiwara, Demna Gvasalia and Marcelo Burlon.

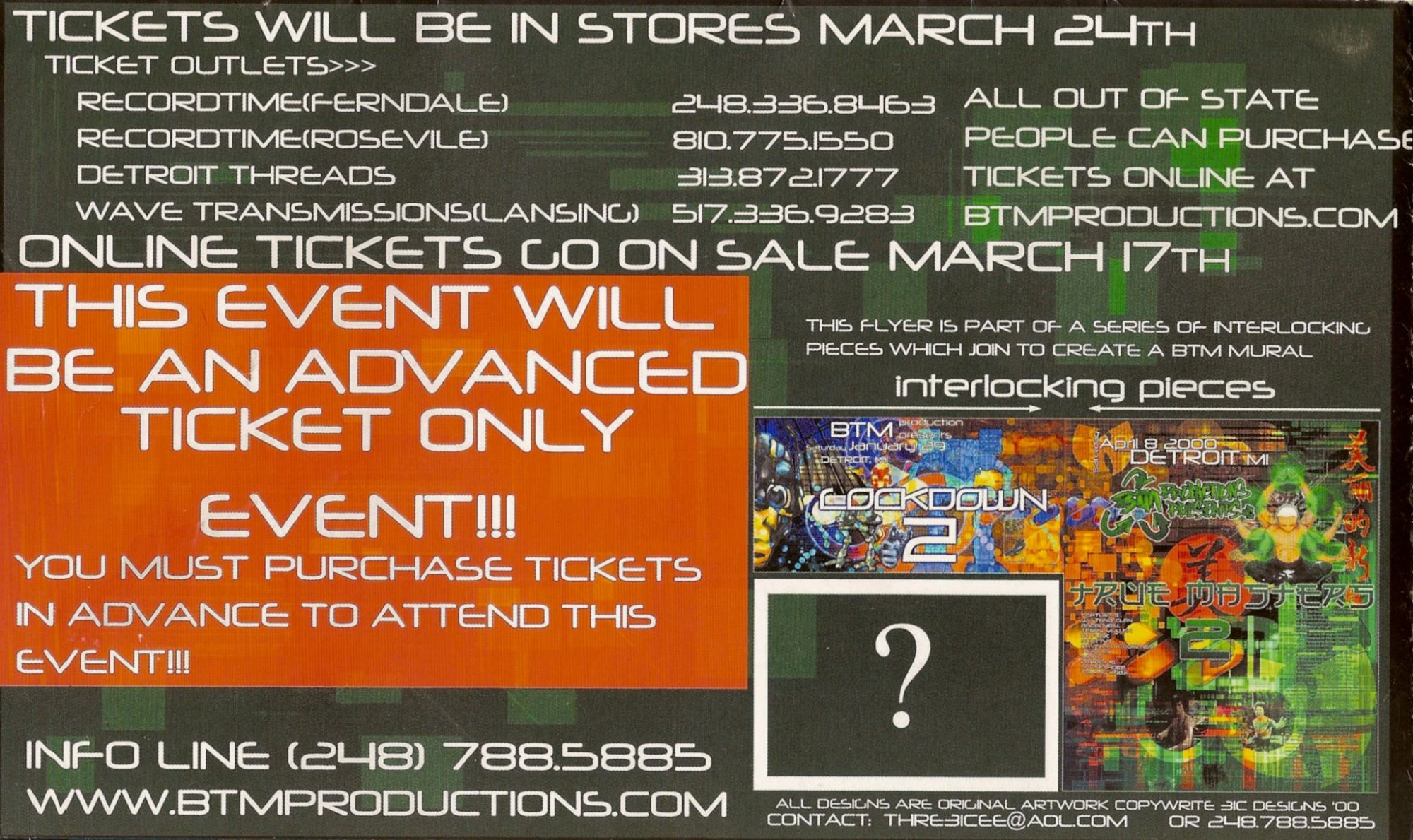

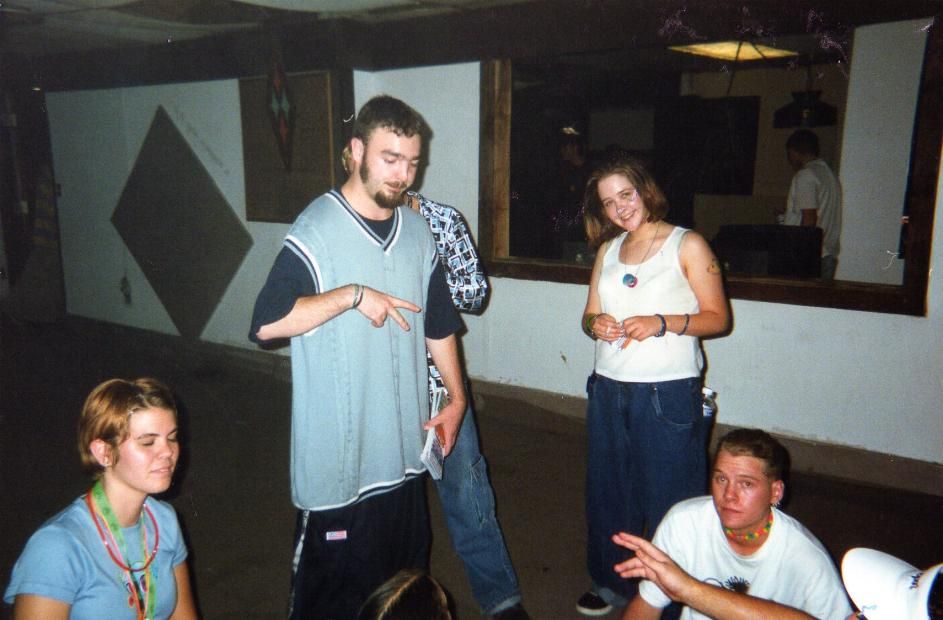

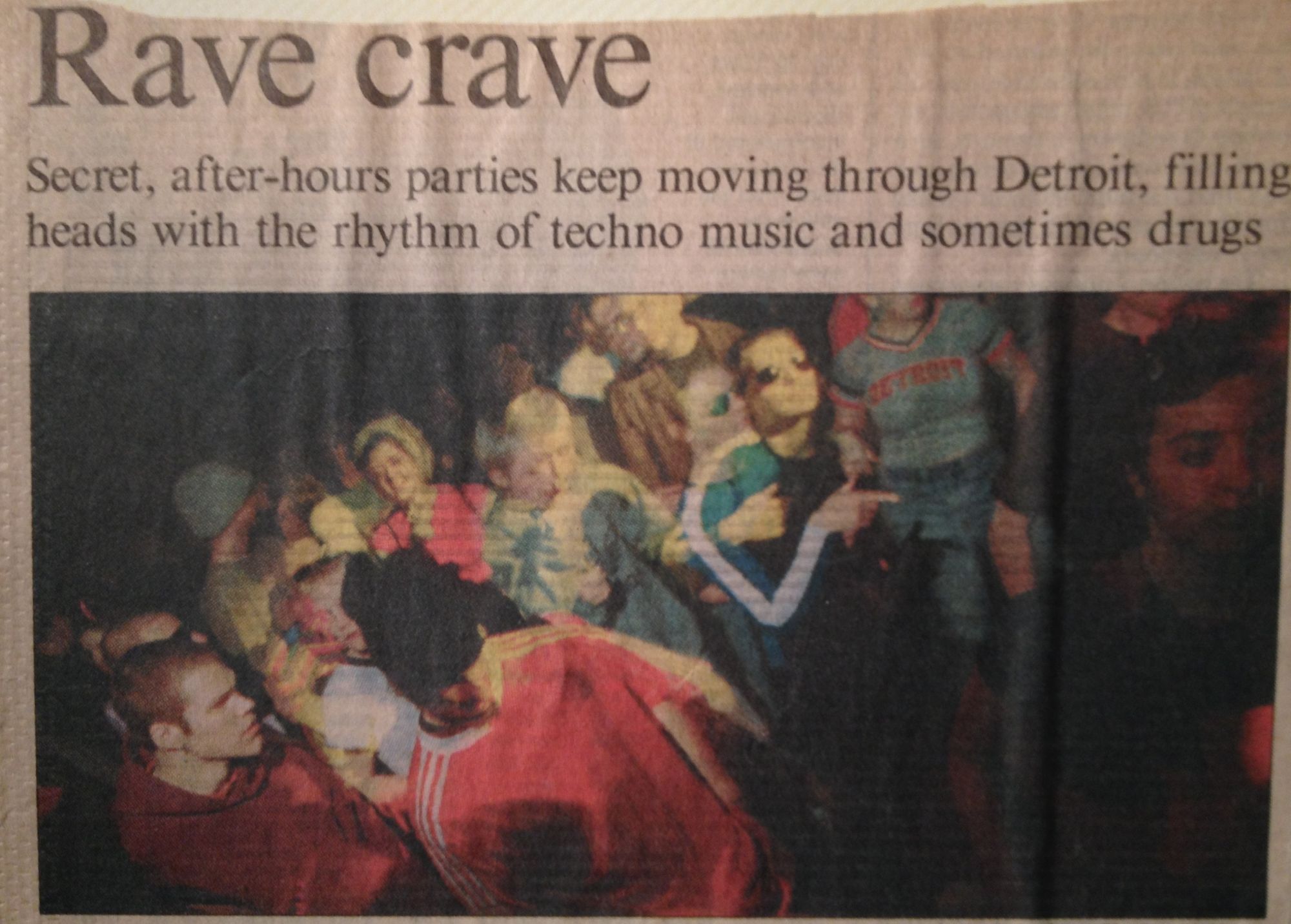

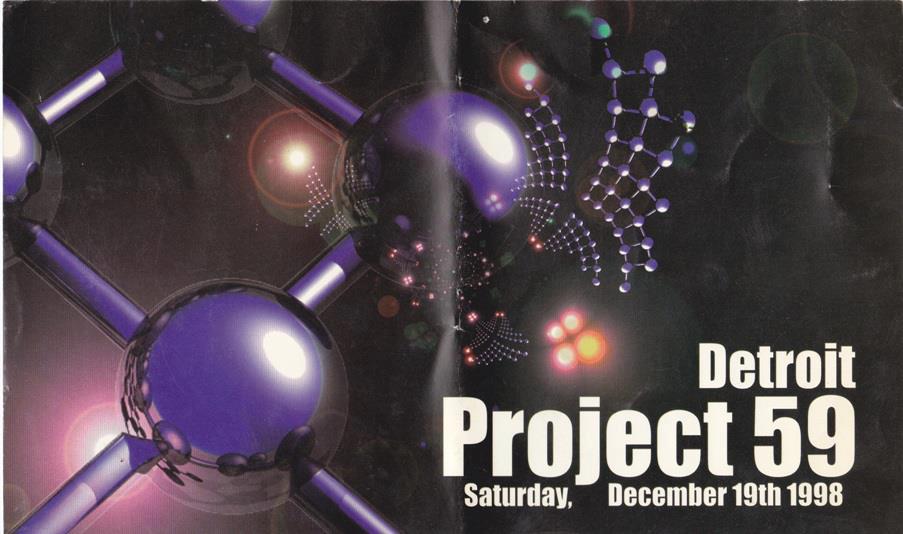

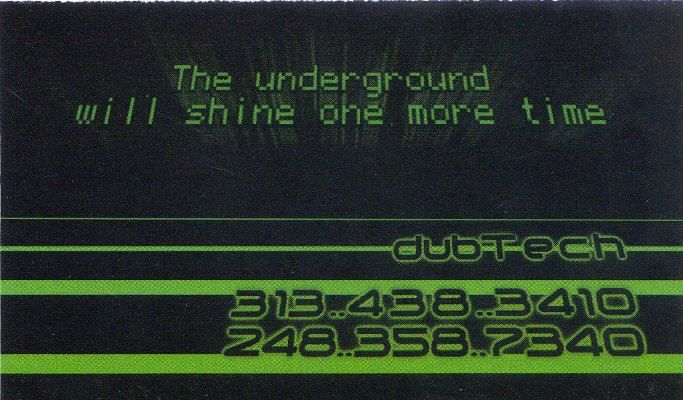

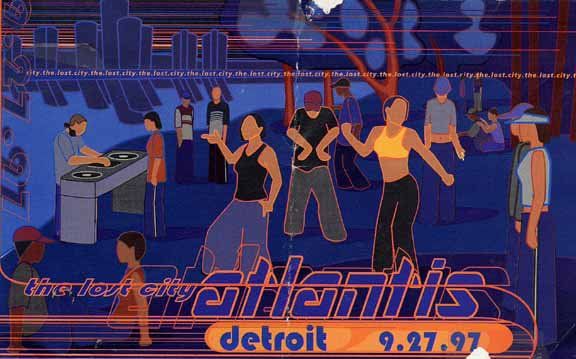

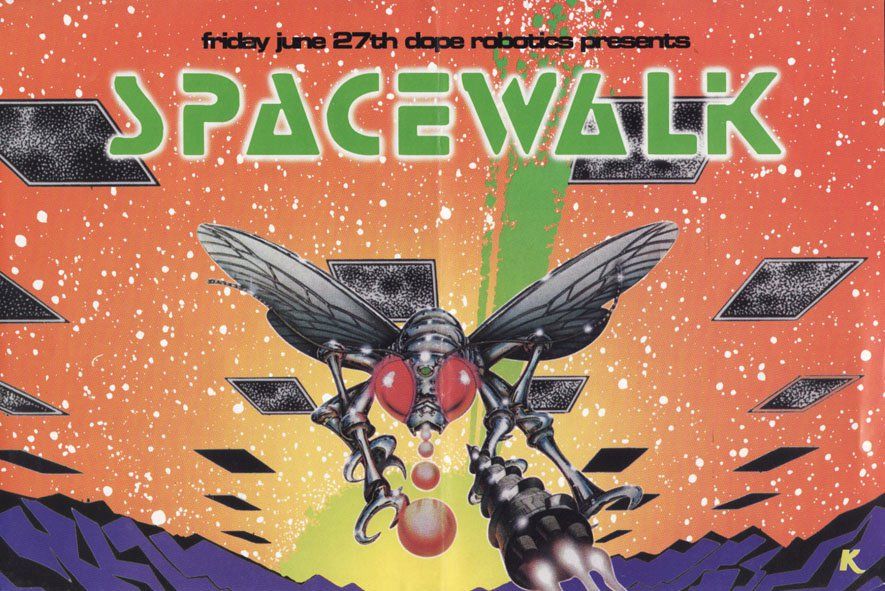

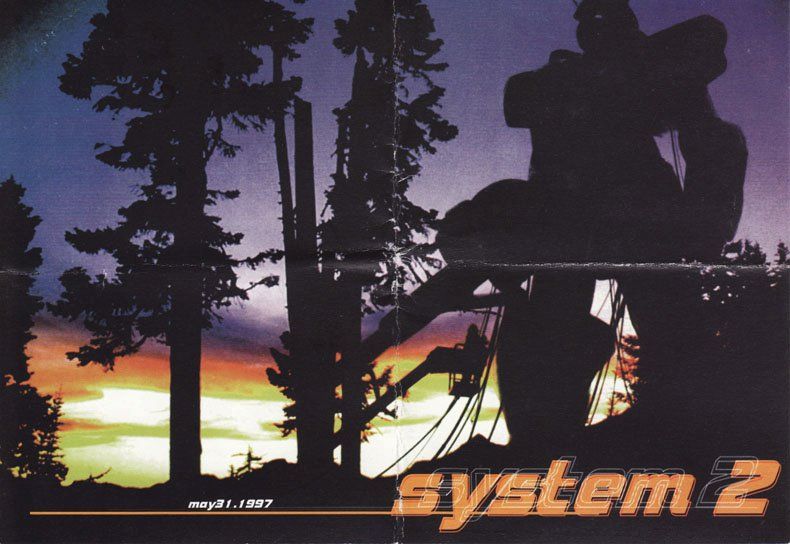

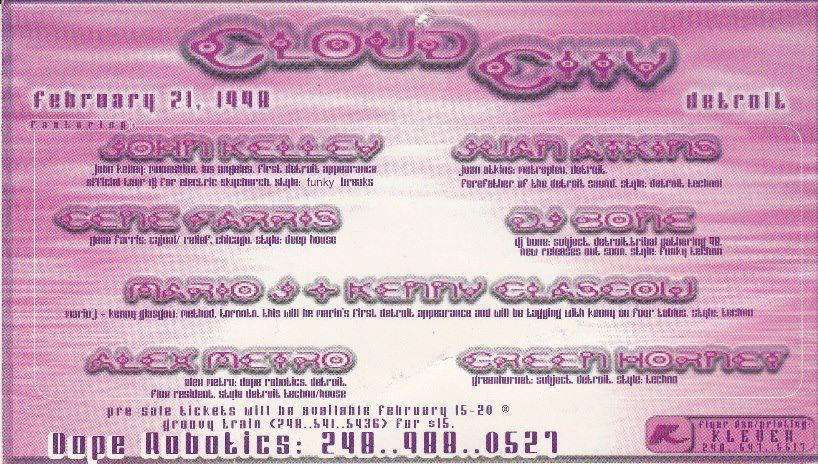

In an interview with 032c, Daniel Lee also explained the origin of his interest in the world of clubbing: when he was young, going to dance was a liberating experience for the designer, an escape from the provincial limits of his English town – and even today techno is the music he listens to when he works late in his atelier. Returning to Detroit after its passage to Berlin means returning to the birthplace of techno and clubbing. It was there that Juan Atkins, Kevin Saunderson and Derrick May, known by the collective name of The Belleville Three, who began as teenagers to create experimental music at home and who already in 1981 were the go-to-music of Detroit parties – channeling on the one hand synthpop and European disco and on the other combining a fascination for post-industrial sound, robotics and for the futuristic aesthetics that permeated the cultural atmosphere of Detroit, a city dotted with desolate ruins and abandoned industrial complexes with their huge machinery but which also hid the hope of a social transformation under the aspect of science fiction imagination. The techno inspirations of belleville Three and other groups such as Cybotron were Japanese and European groups such as the Yellow Magic Orchestra, Cerrone and Visage but also Giorgio Moroder and in particular his hit I Feel Love sung by Donna Summer. The young generations of the city, surrounded by socio-economic desolation, listened to new music during legendary raves regaining possession of those urban spaces that the mechanisms of macroeconomics had destroyed forever: the old Packard factory, the nameless addresses such as 1217 Griswold Street, the Eastown Theater.

The success of the first wave of Detroit Techno fueled a second one, during the 90s, which lasted for at least another decade and a half the status of the capital of underground clubbing that the city enjoyed. It was during this second wave that names such as Jeff Mills, Carl Craig, Richie Hawtin and Carl Cox were involved in the city's music scene broadening its horizons internationally – a process that culminated in 2000 with the first mythological Detroit Electronic Music Festival at Hart Plaza which had visitors from all over the world and later became the most important electronic music festival in the USA, as well as a platform from which numerous international talents emerged. Both at this festival and in the origins of techno there is an eclectic and international nature, which welcomes influences from artists from all over the world and reworks them according to the language of a very precise community. It is therefore interesting to note how the musical genre was born from a reinterpretation of eurodisco and Italo-disco as if to create a parallel between the union of European and Italian culture with the American one with the show of a brand that, after all, was born as totally Italian (perhaps one of the few fashion brands to bear the geographical indication in its name) and is now owned by a company French and creatively directed by an Englishman who has studied in London and Paris.

The choice of Detroit could also be indicative of a growing interest of the brand towards the American market. According to a report by Mastercard SpendingPulse reported by WWD, spending in the luxury sector increased by 118% in America in July compared to 2020 and by 54% compared to 2019. Specifically, Kering, which owns Bottega Veneta, saw a 263% increase in sales in the second quarter of the year in North America and another very recent CNBC report shows how, after the pandemic, the richest 10% of Americans now own 89% of the country's stock while the volume of the stock market itself has increased by 40% since January 2020. A record concentration of wealth that has made the luxury market in the USA the first in the world, with a turnover of 65 billion annually in 2020 alone according to Statista, and which therefore has attracted the attention of large conglomerates to the United States. Not surprisingly, last May, Bottega Veneta was the first luxury brand to open a store in Williamsburg, the main "center" of Brooklyn gentrification. Erwan Rambourg, global head of consumer and retail research for HSBC, explained to WWD:

«If luxury demand were just about wealth, the U.S. would have already been much bigger, so recent financial incentives — strong equity markets, staycations, stimulus packages — may have had an influence, but the real shift is more psychological than financial there. From a psychological perspective, the so-called guilt factor that was prevalent after 9/11 and again after the global financial crisis seems to have evaporated. The U.S. luxury market is still held back by a value-for-money culture, but a younger, more diverse, wealthy consumer is now a lot more willing to spend on high-end labels».