Matthew Williams, the accusations of plagiarism and the true role of creative directors Inclusive fashion means inclusive brand storytelling

Yesterday afternoon Diet Prada launched a new call-out to one of the heavyweights of the fashion industry, Matthew Williams. The accusation, originally thrown by former model Athena Currey, is that of having copied the work of the designer Benjamin Cho, who died in 2017, replicating his clothes composed of silk braids that wrap diagonally around the body creating an effect of transparency. A dress created with this technique was one of the workhorses of Givenchy's last FW21 collection, also recently appearing to Beyoncé in a shooting for Harper's Bazaar, but, as highlighted by Diet Prada, the resemblance to the clothes of Benjamin Cho's SS01 collection is something obvious. Further additions in Diet Prada's IG Story, which also include a DM from Paper Magazine's fashion editor, Mario Abad, claimed that Cho had not been mentioned in the press release – as well as no article about the collection mentioned him. To make things more complicated, there is also the friendship between Cho and Williams, who had worked for the designer at the beginning of his career and who, after yesterday's comments, wrote an IG Story, then canceled, in which he recognized that the dress was an "homage" to Cho.

The complicated issue of fashion "homages"

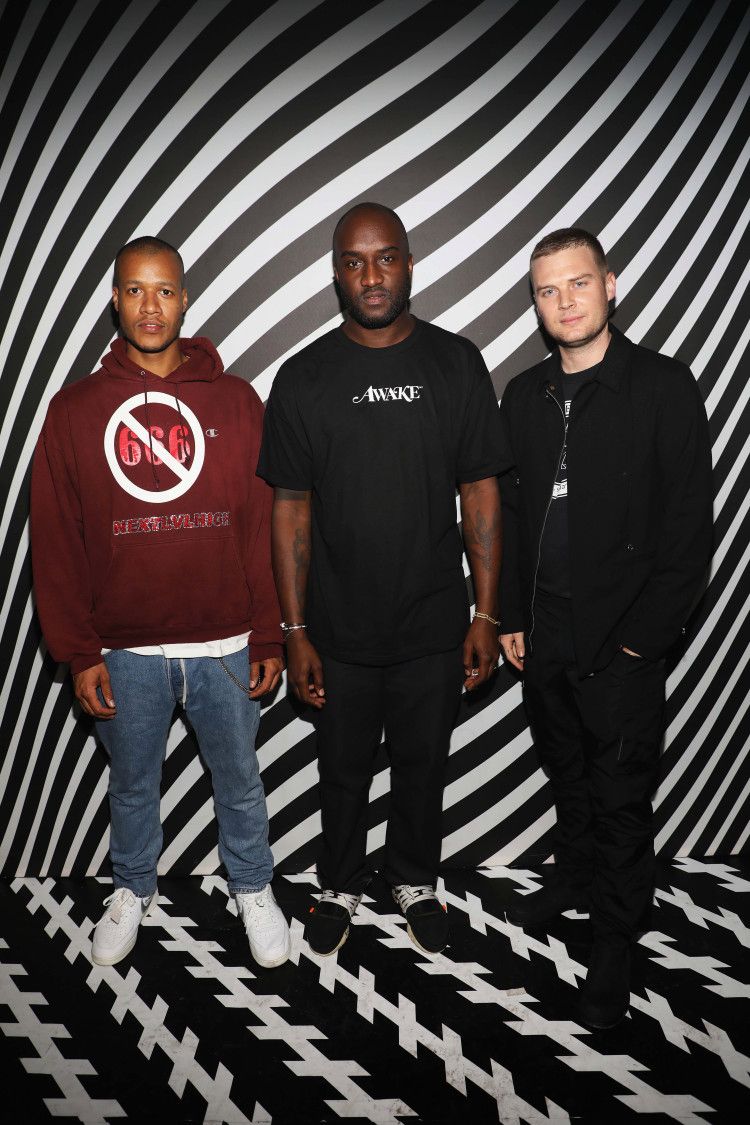

The allegations of plagiarism are not complete news for Matthew Williams' Givenchy, which just eight months ago was accused by K. Tyson Perez, founder of the Hardwear Style brand, of copying the design of a leather bucket hat decorated with a metal zipper - then withdrawn from production after the call-out. Another tribute by Williams during the Givenchy FW21 show was to the famous Armadillo Boots by Alexander McQueen as well as to various elements that reminded the most fashion-savy of the works of Martin Margiela and Helmut Lang. But the question of "homages" in fashion goes much further back in time: almost every brand has been accused of copying and plagiarizing others, indeed, it is from an accusation of plagiarism that the relationship between Gucci and Dapper Dan was born, while the accusations of plagiarism have always rained down on Virgil Abloh, with the most recent dating back to the day before yesterday, and over the years have involved everyone from Balenciaga, Versace, Chanel, Moschino, Dior, Michael Kors and Bottega Veneta just to name a few.

The "homages" of this type date back to the very origins of fashion as we know it: in the video-essay The Designer Debate: Balenciaga vs. Givenchy, fashion historian Henry Wilkinson tells how Balenciaga himself drew heavily from the work of couturier Madeleine Vionnet and how Hubert de Givenchy's designs were often created in a sort of aesthetic osmosis with those of Balenciaga. All these episodes, which are perhaps too numerous to count, are part of the very nature of the fashion industry but, given its political and economic dynamics, as well as creative, they become very problematic when a large international company subtracts concepts from independent designers, niche without giving them any credit or reward whatsoever when in fact a very simple mention and maybe even a form of commercial agreement that can help the smaller designers to be known for their own merits. But such a practice, to which the big fashion brands are reduced only if forced by public opinion, is not appreciated because it would break the fundamental scenic illusion that sees the creative director as the absolute demiurge of a brand's creativity.

The protagonism of creative directors

In a recent interview with Highsnobiety titled The Fashion Industry Says It's More Open, But Is It Really? conducted by Cristopher Morency, independent journalist and youtuber Odunayo Ojo said:

«One frustration I've always had goes back to this system where designers like to act like everything is them, when it's not. And that's something I didn't realize until I started working in fashion. As a creative director, you had a lot of assistants who brought you those ideas. And by the time the final product was made, you probably have a 5 percent input, but they take all the credit, and they have this mystique around them.».

Underlining in fact how the narrative of the press offices often describes the creative directors as movie magazines describe the directors, that is, as the individual authors of a work that has been directed by them but remains the collective effort of a large team that stays in the shadows. The difference is that at the cinema the credits list the name of even the last of the assistants, while at the end of a fashion show to go out on the catwalk and bow there is only one person who appears illusionistically responsible for the entire collection. The illusion is necessary for strictly narrative and commercial purposes: we need a single face, a single superstar that the public can call by name, and therefore if there are too many inspirations or references you would run the risk of jeopardizing the pivotal role of the creative director – but the fashion world is moving in new directions, where the collection becomes more and more a collaborative and open model, as was for example the last Dior Homme show, in which the creative director deviates from the fictitious role of absolute author and becomes the curator for a community that has contributed to the artistic and productive effort.