Does "Cruella," Disney's new movie, demonize fashion? Emma Stone's new film is beautiful but continues to represent fashion through the usual clichés

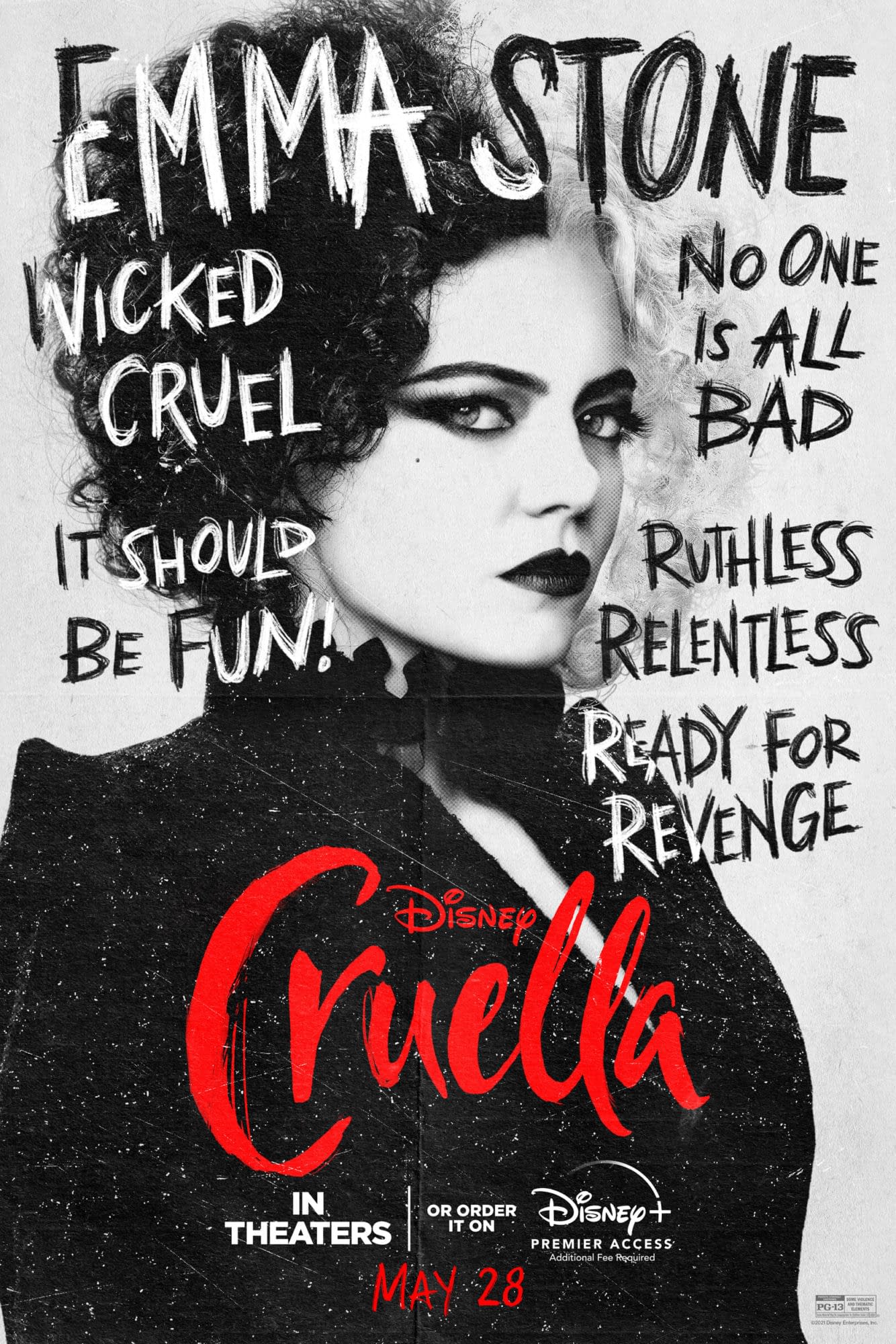

Arrived on Disney Plus last Friday, Cruella was a particular film compared to those found in the Disney catalog. In the slew of live-action remakes of the great cartoon classics with which entire generations have grown up with, the film is certainly a more mature and dark proposal – all the more so since it is anchored to a kind of historical reality, '70s London, and concerns a more concrete than fairytale world: fashion. The film undoubtedly has its own fashion moments (one in particular, our favorite, includes a garbage truck and a giant train of tens of meters) but a very authoritative voice, that of Vanessa Friedman, has taken off the pages of The New York Times to accuse the film of propagating the stereotype of a "toxic" fashion:

«And thus does the demonization of fashion play on; its role as shorthand for all that is morally corrupt and venal in the world continues. It is one of Hollywood’s most beloved, if increasingly inane, clichés. For as long as there have been films set in the fashion industry, that world has been portrayed as a gilded cesspool of caricatures, cattiness and occasionally criminality, with a twisted value system far removed from the cornfield heart of everyday life — no matter whether the film in question is a comedy, dramedy, satire or musical.».

But how does Cruella represent fashion?

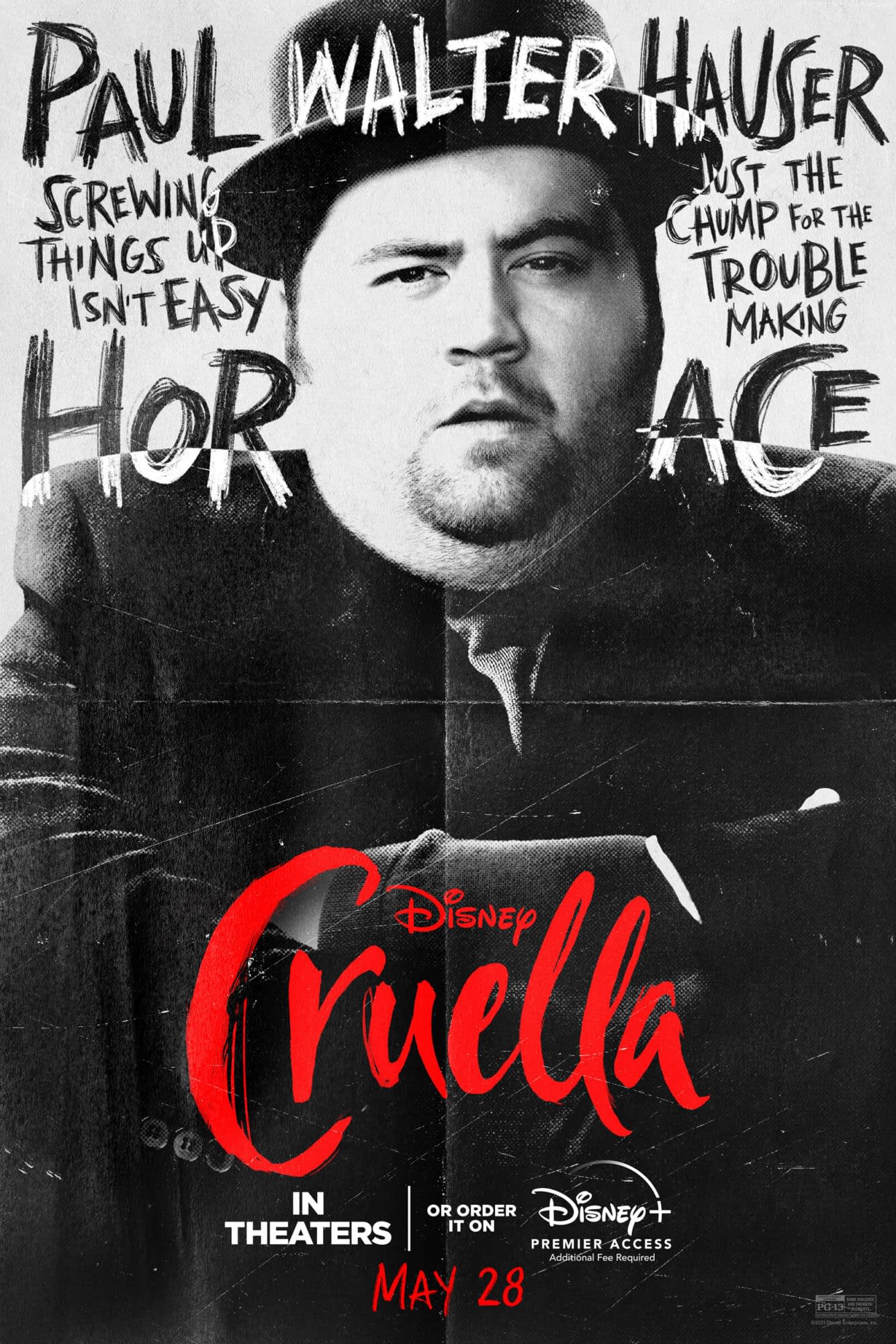

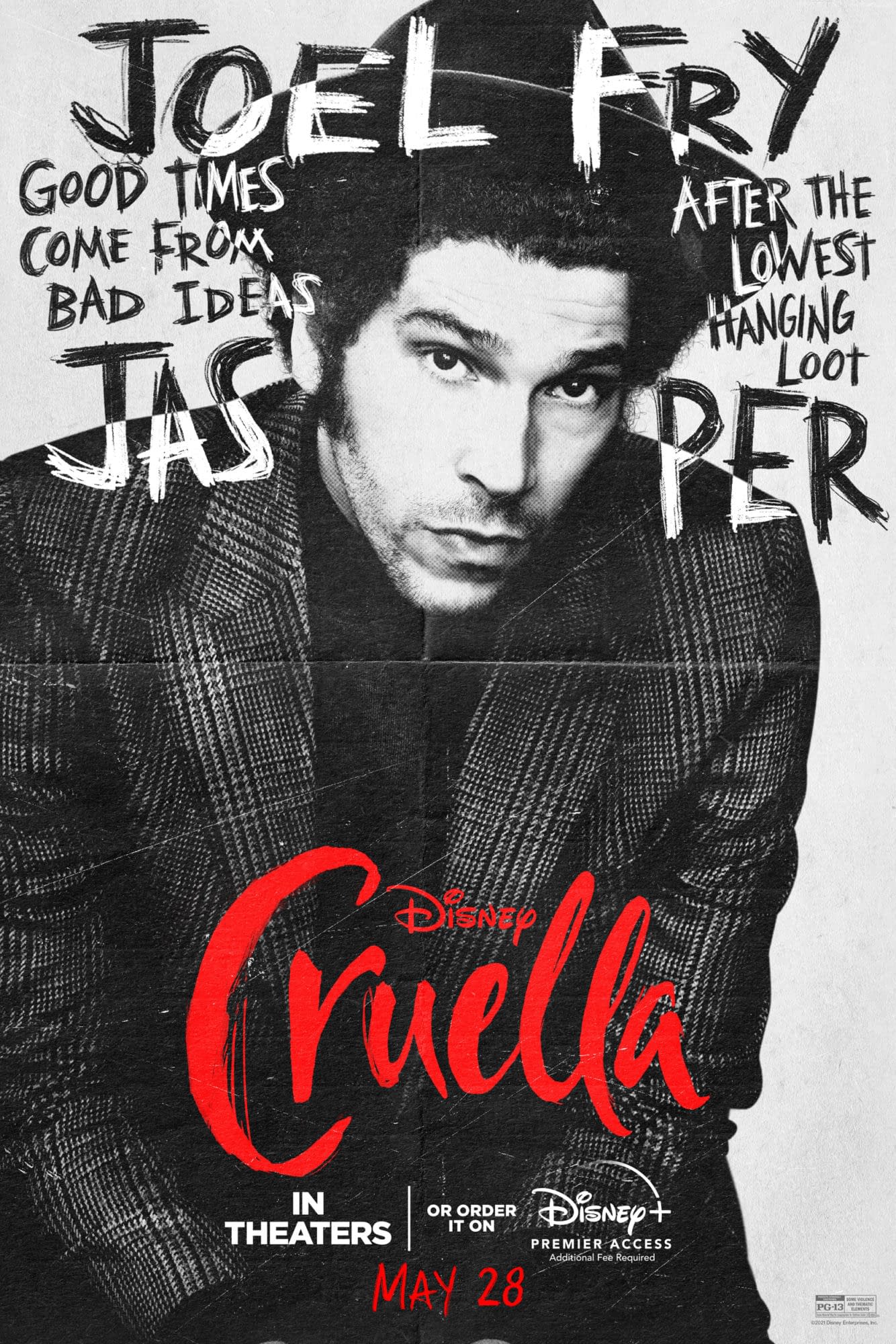

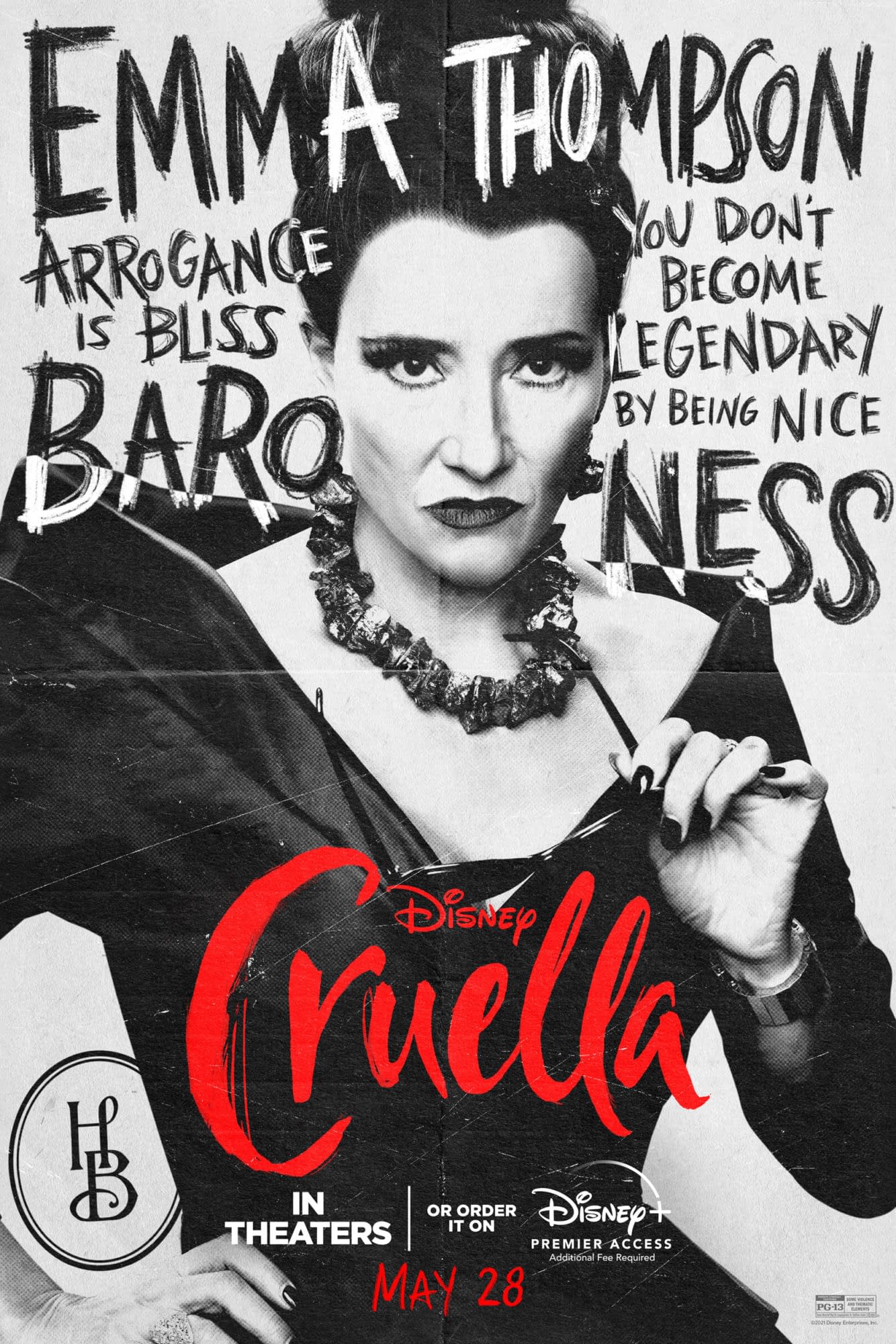

Vanessa Friedman's criticism does not involve the entire film, only its depiction of a fashion industry that seems to be interpreted as a kind of "empire of evil". In fact, as the article points out, director Craig Gillespie has not consulted any fashion insiders, nor is he a lover of fashion movies. Which is strange because the film represents almost convincingly the workings of a fashion atelier, with the various design teams making proposals that are then accepted and reworked by the creative director but also with the sad reality of the contractual obligations of designers and the creative difficulties of composing a couture collection. Another thing that the film captures well is the generational gap between a world of à-la-Christian Dior couture and Vivienne Westwood's punk fashion universe – and that's why the film's villain, The Baroness, really looks like the caricature of a fashion designer with her bonkers outfits completely (Friedman rightly wonders which designer would ever work wearing their own haute couture creations), her folding razor carried in her purse and her talk about the "killer instincts" that serve to work in the fashion world. In this case the opposite of her would be Estella/Cruella, decidedly more "democratic" in her methods but no less eccentric than her antagonist.

A very fair criticism that Friedman makes, however, is the association between the role of the female fashion designer with the figure of the "evil queen" – a stereotype in the media representation of the woman of power who is de-feminized and transformed into an evil and authoritarian figure. Cruella herself, at the end of her character arc, becomes a figure similar to that of the antagonist – which makes sense considering that the film is about a classic villainess of the Disney world, but that perhaps she would need further study, even though it is a family film whose basic message still remains that of self-expression. However, a problem remains: fashion is still represented as a playing field of childhood rivalries, narcissistic or hyper-servile personalities and the romanticization of fashion paints it indirectly and unilaterally as a somewhat petty world, fueled by personal feuds, where personal style and authority become synonymous with abuse and despotism.

A justified sterotype?

The film, however, perpetuates the cliché of fashion as an un-human business, in which a glamorous kind of "meanness" becomes the surrogate for professionalism, humanity and preparation. A typing that is not harmful in itself but that adds to the line of tyrannical and narcissistic film designers/ editors: think Miranda Priestly of The Devil Wears Prada; think of Netflix's Halston, all drugs, sex and discourtesy; think of Zoolander's hilarious Mugatu and Daniel-Day Lewis in Phantom Thread. At this point the question arises as to why the fashion world has become the target of this cliché. It is certainly true that, in the age of corporate responsibility, democratic design, Diet Prada and fashion communities, the idea of the fashion industry as an "empire of evil" is somewhat dated but in fact the combination of aggressive brand marketing, statements of design democracy and elitism inherent in the concepts of "luxury" and "exclusivity" has created a kind of prejudice against this world. Joanna Coles, former chief content officer of Hearst Magazines, interviewed by Friedman for the article, emphasized this aspect:

«It often feels that not only are these designers pretentious and the clothes impossible to afford, but you are being tantalized by something you can’t have».

And to some extent this is true: Diet Prada itself, as an independent fashion magazine, has brought to the spotlight the plagiarism, abuse, elitism and problematic aspects of an industry that is, at the end of the day, an industry like all the others with its positive and negative sides even if sometimes a little out of this world. None other things, these various faults do not fall only on creative directors and fashion designers - figures that are often associated with fashion without intermediates, without considering that a creative director is an important gear but inserted in a much more articulated and complex "machine" made up of boards of directors, style offices, trend-hunters and buyers. The era of the designer-emperor is over - although their figure is often mythologized and creative directors take full credit for collections actually designed by vast teams.

What mainstream audiences know about fashion are often the downsides: from the soap opera that had become the life of the Gucci family in the 80s to the various scandals about the world of modeling, going as far as recent events such as Bottega Veneta's Berlin party, the story of Alexander Wang's sexual harassments and Balenciaga's "thefts" from independent designers – many of the news that has visibility are the least pleasant. At the same time the reality is more layered and complex than this and often finds it better represented in documentaries. One of the best and most famous is Dior and I, which chronicles Raf Simons' debut as creative director of Dior in 2012. Simons, one of the most celebrated and appreciated creatives in the fashion industry, is a long way from the idea of a despotic stylist that is seen in many films: Simons shows up at work in a normal blue sweater, he is kind to everyone, even gets to cry before the show. And while it's also true that at the bottom of every cliché there is a bottom of truth – it might be time to talk about all the other truths about the fashion world.