It's not just a store The mystic of Supreme stores: from the first in SoHo to the last one just opened in Brera

Today, the word Supreme evokes almost immediately a red rectangle with the word printed in Futura Bold Oblique. Like a déjà vu, the brand has managed to embed its logo in the culture and collective memory thanks to a specific, unique brand building, which has already entered the marketing books. It involves the world of reselling, collaborations, artificial scarcity but often one aspect of the brand is overlooked: the stores. Supreme, in fact, before being a brand, was born as a shop and has never - except for a few very short periods - distributed outside the network of the current thirteen locations around the world, including the one in Milan just opened in Corso Garibaldi. The store from its early days to the camp-outs is the place where the mystic of the brand, fueled by history, resell and much more, takes physical presence with a cyclical ritual that makes the experience of entering Supreme different from any other store.

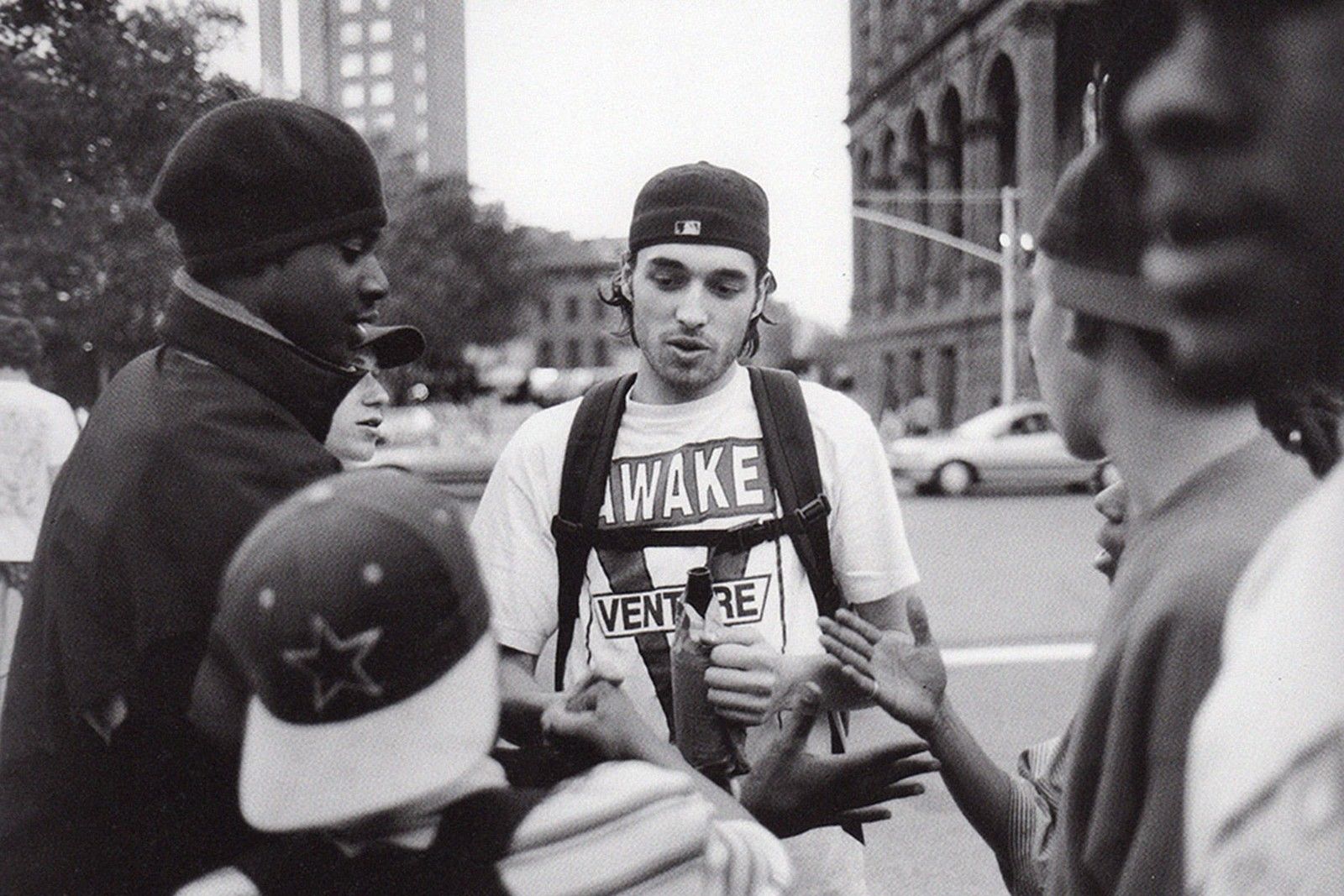

It was the spring of 1994 when James Jebbia, a former Union and Stussy shop assistant, rented the walls of a decrepit space at 274 Lafayette Street, Manhattan, New York City, with a deposit of 12 thousand dollars. In the first half of the 90s the city was still gloomy, bent first by financial default and then by the first great wave of crack; the city offered no jobs, had the highest crime rate in the United States, and many central areas lived in decay and neglect; Taxi Driver and The Warriors are two films that reflect the narrative of the time. Despite poverty and social problems, the sidewalks of New York remained a place where different cultures influenced each other: the skaters of Washington Square (as portrayed by Harmony Korine and Larry Clark in Kids), the black community of Harlem, the penniless artists of SoHo. Lafayette Street was often crowded by drug dealers or prostitutes, and the shops were mostly small family businesses, but there was also the legendary Keith Haring pop store. SoHo's gentrification process was already underway, but it would take a few more years to complete, with the independent galleries moving across the Brooklyn Bridge to Williamsburg.

Jebbia had grown up in the London of the subcultures of the late 1980s, where stores like Sex had shown the way, but above all he had worked in some of the first streetwear stores of NYC: Parachute, Union and then had convinced Shawn Stussy to open the first store of his brand in New York. Jebbia was interested in high fashion - he was and probably still is a fan of Helmut Lang - and in subcultures, he was not a skater, nor an artist, but he managed to synthesize the richness of the various influences that met on the streets of New York by creating a shop that offered a singular mix of elements. The space of the first store was airy and bright - strange for a skate clothes shop - the products were maniacally folded on the shelves in a Swiss order, in the shop windows there were televisions looping videos of Muhammad Ali, Taxi Driver scenes and skate videos. A penetrating smell of flowers and bark could be smelled in the air, thanks to the Nag Champa incenses - which will remain a tradition of the brand - while the speakers played Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), the first album by the New York collective, the record that revolutionized American hip-hop. A bewildered passer-by would have thought more of an avant-garde art gallery than a skate shop and entering magnetically attracted by the red box logo, the shop assistants would quick in showing passers-by they were in the wrong place and that they were not necessarily welcome.

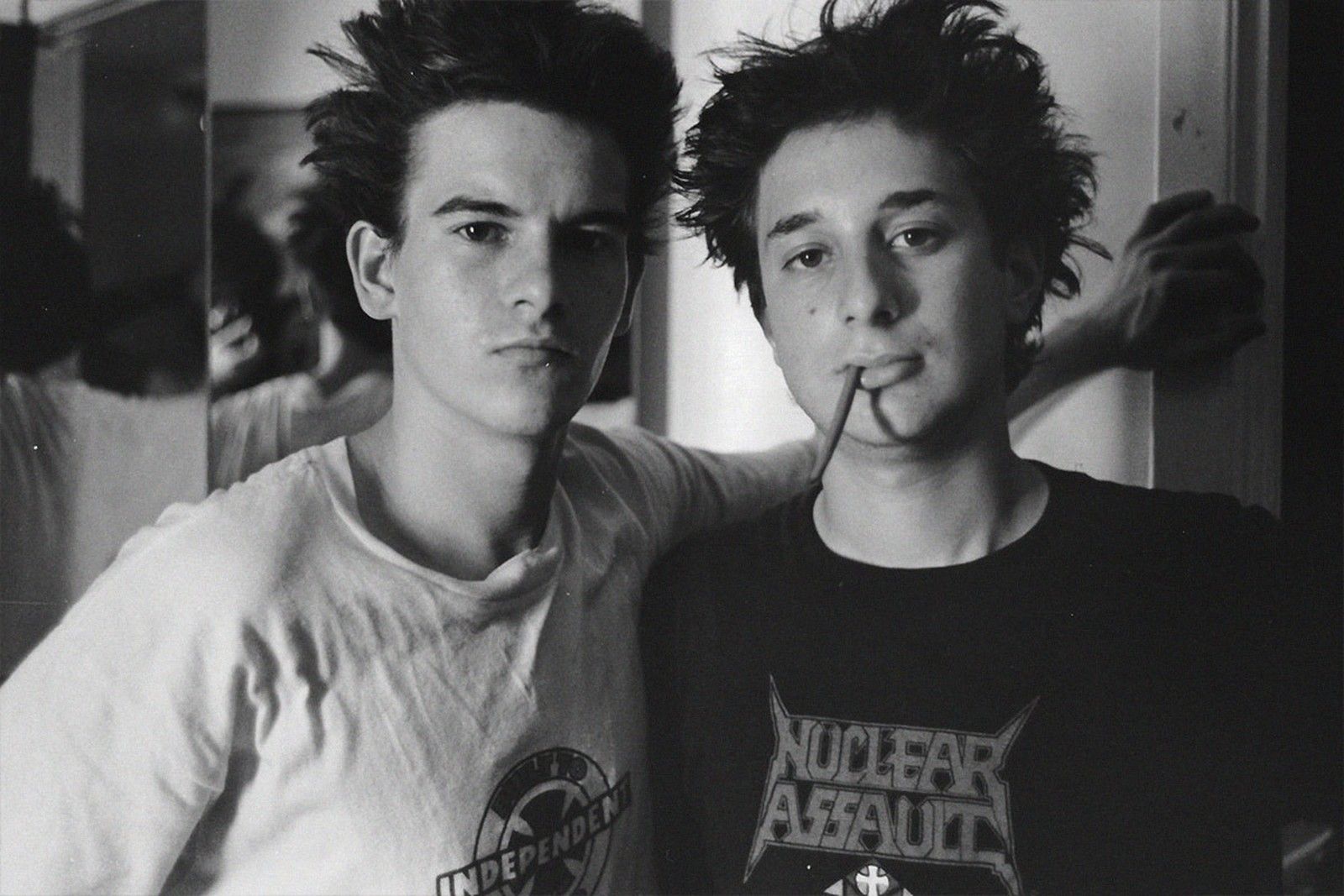

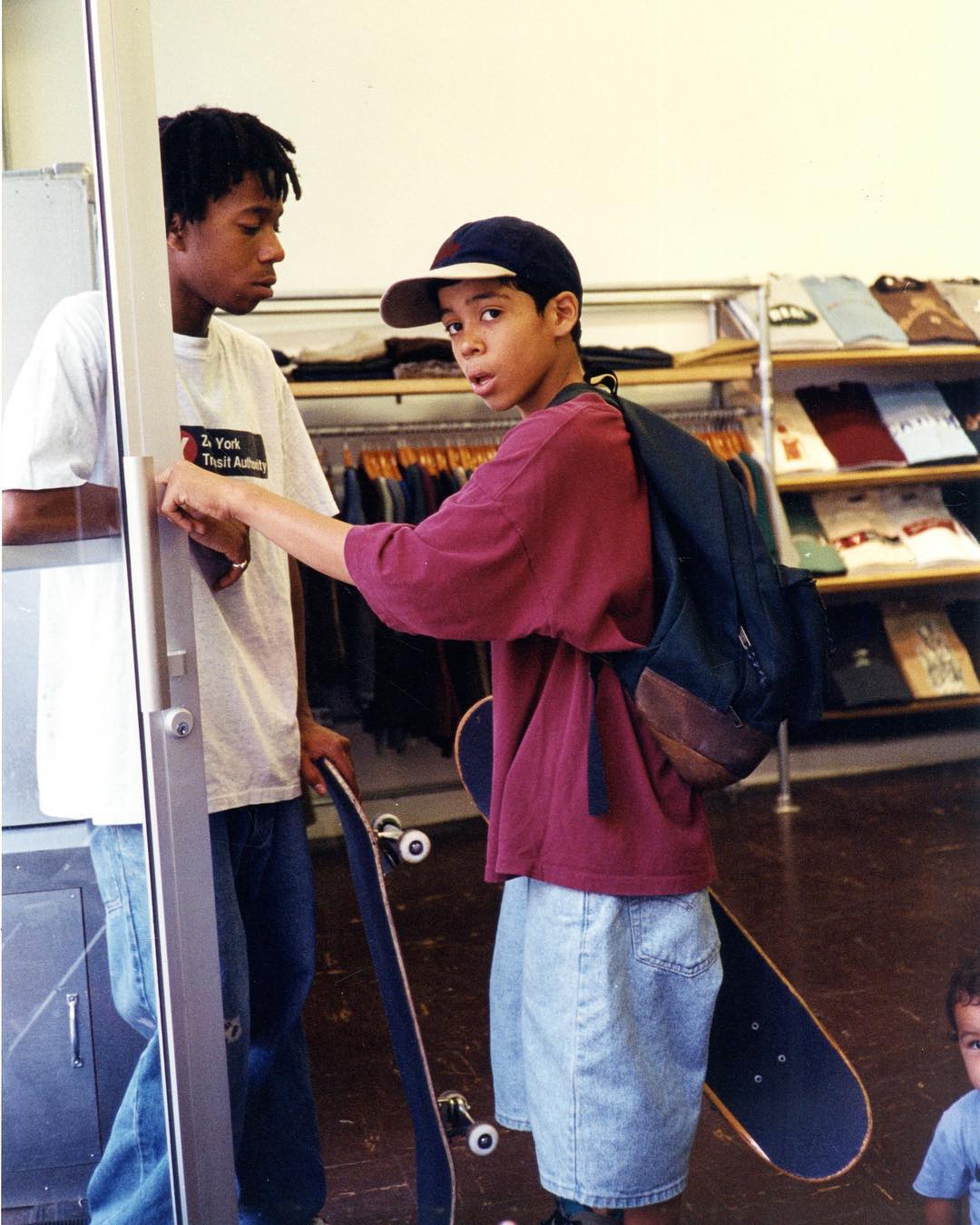

Skaters colonized the shop, spending afternoons doing tricks and drinking beer, and some of them started working in the store and then became cult figures of the New York underground such as Giovanni Estevez, aka "Gio", and Aaron Bondaroff. For the skate culture - not being a sport with rules and scores - attitude is everything: real recognizes real, for this reason, the shop was a meeting point for Larry Clark's Kids and ended up attracting the entire underground art scene of the era, among them the street artist Rammellzee and the actress Chloë Sevigny. The high fashion of glossy boutiques was galaxies away, despite a visionary article published in 1995 in the American edition of Vogue, proposing a bold comparison between the Chanel store at 57 Fifth Avenue and that of Supreme. One of the points in common was the omnipresence of the logo, the other was the exclusivity of the store which at Chanel was fueled by price, by Supreme by an unspecified state: coolness.

The story goes that, in order to work less, the shop assistants terrified potential customers by saying, "Don't touch anything until you buy it," not to have to spend time folding all the shirts. An alienating effect for the public, which often turned into awe, which in turn was subconsciously translated into admiration and aspiration, into the desire to be part of the Supreme club. As already mentioned, it's a dynamic similar to that which occurs in sacred places: churches, for example, are built in such a way as to make the word of God tangible and concrete, the faithful who enter them experience a mixture of fear (a simple man in the presence of the greatness of God) and aspiration (desire to rise to the greatness of divinity). In the case of Supreme, buying becomes an act of faith: it means joining a club of elects. Of course, Bondaroff argued that theirs was just a tactic designed to work less. But, above all, those discouraging and "terrifying" customers can rightfully be considered the beginning of Supreme's marketing strategy. Aggressiveness towards potential buyers is in fact still one of the main guidelines. A strategy that today translates into scarcity and inaccessibility to the product. And here it's that buying continues to be a leap of faith because the moment you cross the queue at the entrance again and are admitted back into the store, that particular product is not necessarily still there for you. This creates in the consumer an immediate and unstoppable desire, which results in the purchase of that particular item in the short term, and that in the long run results in the strengthening of the cult of the brand. In this sense, entering a Supreme store takes on the meaning of an initiatory test. And it has always been like that, whether it's having the same attitude as the 1994 underground skaters or spending the night camping out on the sidewalk in 2019 not to miss out on a new product. The point is not to buy an item. The point is to be there and be part of that community. It's no coincidence that Supreme's current thirteen global locations are all very similar to that of Lafayette Street, especially when it comes to the minimalist organization of spaces and the consequent sacral patina. And just like in sacred places, it's forbidden to take out your mobile phone to take pictures or make videos.

Even the attitude of the shop assistants has never changed and the figure of the store manager has always been entrusted during the various openings OG characters of the local skate scene, not surprisingly in Milan it will be Gianluca Quagliano. What has changed over the years are the locations and neighbourhoods - in Milan, the store is in Brera, in Paris in the Marais, in San Francisco in Market Street - but above all the public: from the skaters of '94 to the hypebeasts of recent years. A lot of speculative talks can be made about the brand's bourgeoisie and the fact that it has reached the value of two billion dollars (and is now owned by a large group like VF Corp) becoming exactly what in '94 it made fun of and despised, yet there is a coherence - sometimes ironic, sometimes surreal - in Supreme's ability to interpret reality, social and aesthetic changes. The skaters' rituals have been replaced by online drops, the afternoons spent in front of the store smoking and skating by the camp-outs, the idols of street thugs have become the influencers.

Today Lafayette Street is one of the most beautiful streets in SoHo, where houses and shops have astronomical prices and instead of drug dealers and skaters there are coffee shops that serve excellent matcha tea. In 2019 Supreme definitively left the location where it was born and this I believe is ultimately what makes unique a brand born on a New York sidewalk that has now become a tourist attraction in a shopping street of the fashion capital of Milan: to cross fashion, aesthetics and culture while remaining relevant.