Guide to the style of great Italian songwriters From Lucio Dalla and C.P. Company to Alan Sorrenti's disco aesthetic

Fashion and music have always traveled on parallel tracks, in a relationship of mutual influence. Underground aesthetic movements together with high fashion have often been able to inspire the aesthetics of artists who, in turn, create aesthetic trends that affect streetwear. If in the past it was the album covers or the rare TV appearances of the singers that inspired the clothing of their fans, today, in a much more liquid and voyeuristic way, social media has opened daily windows on the clothing of musicians. Some things, however, never change. If today the likes of Slowthai and Drake are trendsetters with their endorsements of C.P. Company and Stone Island, similarly, in the 80s, an eccentric and brilliant Bolognese singer-songwriter inaugurates this trend. In addition to Lucio Dalla, the entire Italian singer-songwriter scene of the 70s and 80s was able to grasp, both in the texts and in the aesthetics, the imaginary of Italy of the time, influencing and making itself influenced by it.

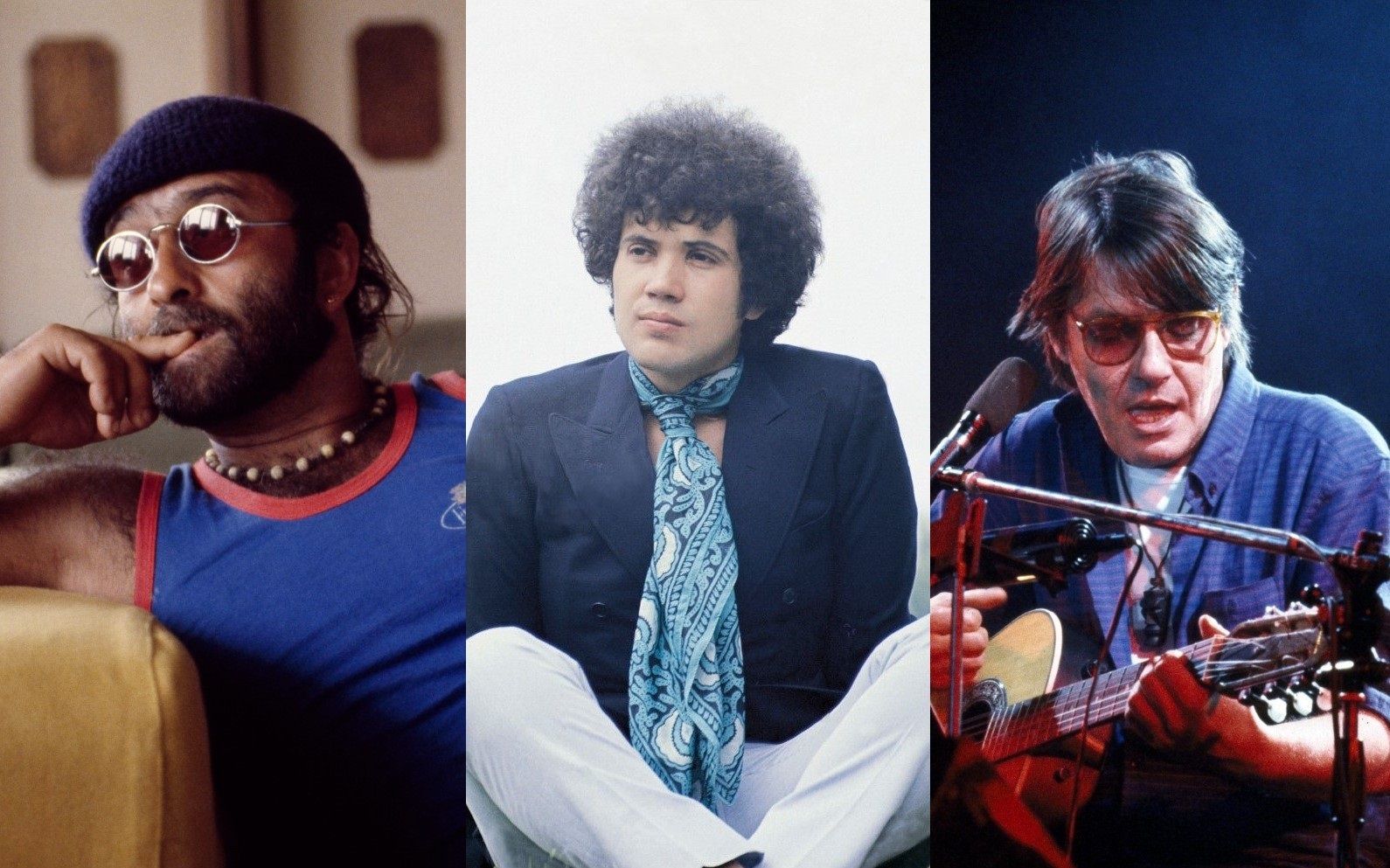

Lucio Dalla & C.P. Company

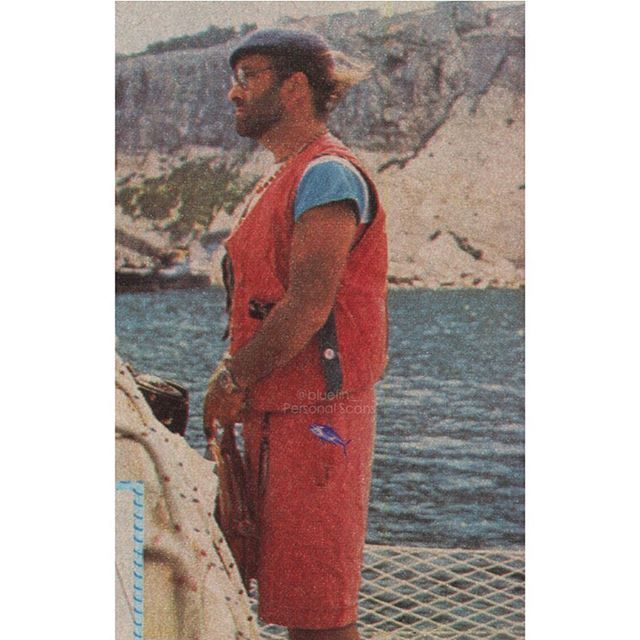

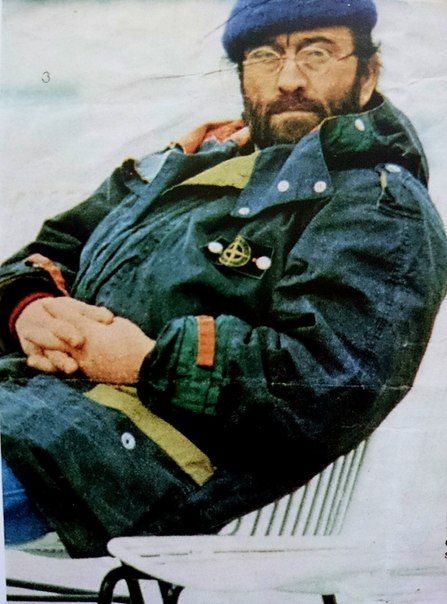

Between 1977 to 1980, with three flawless albums and the hype granted him by Carlo Verdone’s film Talcum Powder, Lucio Dalla turned into a national pop icon and etiquette-setter. Kids would even beg their mothers to knit them crochet beanies in the style of those Dalla wore. Despite being far from quintessential testimonials – with his thin hairline and figure as distant from the show business canons as Elton John’s – Dalla became the face of C.P. Company. His close friendship with the brand’s founder and head designer Massimo Osti, who was extremely fascinated by the composer, resulted in a prolific and long-lasting collaboration between the two.

In the summer of 1979 Osti designed a beautiful tee for the artist’s Banana Republic tour. The event was fundamental for Italian music as it suggested, albeit symbolically, that the country was finally going back to normality after the Years of Lead. Over the following years Dalla would be seen many times wearing C.P. and Stone Island garments, including knitwear, wind breakers, and utility vests. In 1989, at the peak of C.P. Company’s trend, the singer-songwriter even featured on the cover of the brand’s magazine. It doesn’t then come as a surprise that this year, on the 50th anniversary of the brand’s foundation, C.P. Company is dropping a capsule collection in partnership with the Lucio Dalla Foundation.

Guccini, Armywear and Contestation

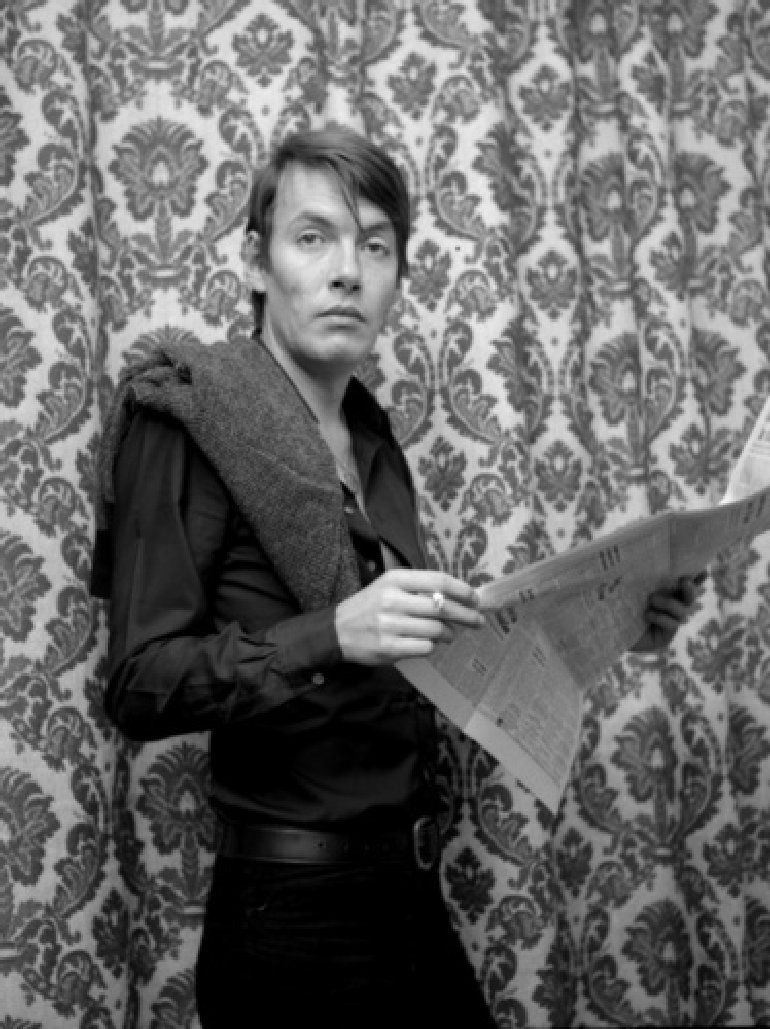

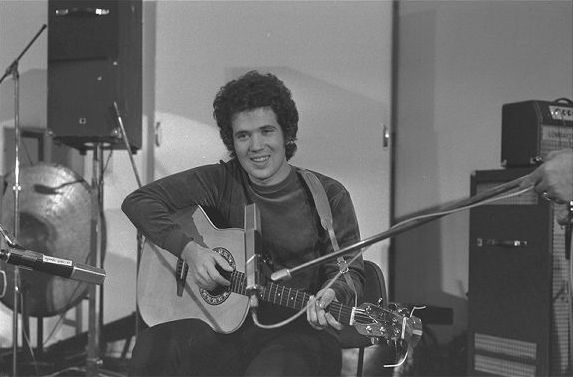

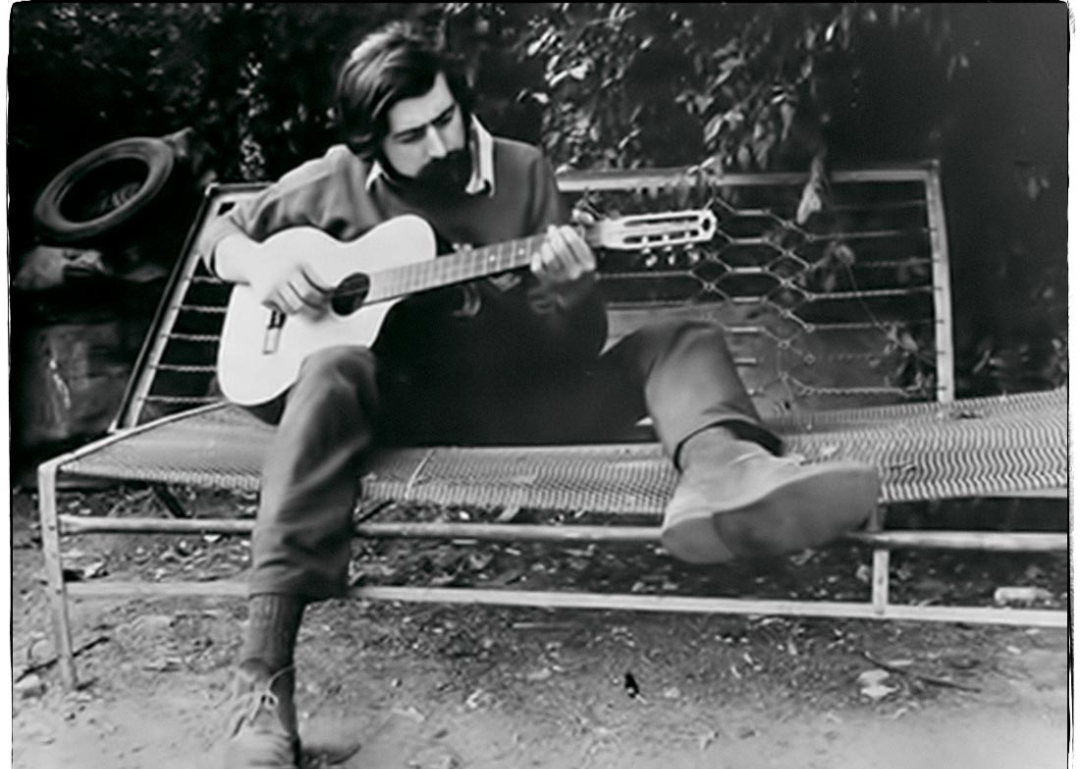

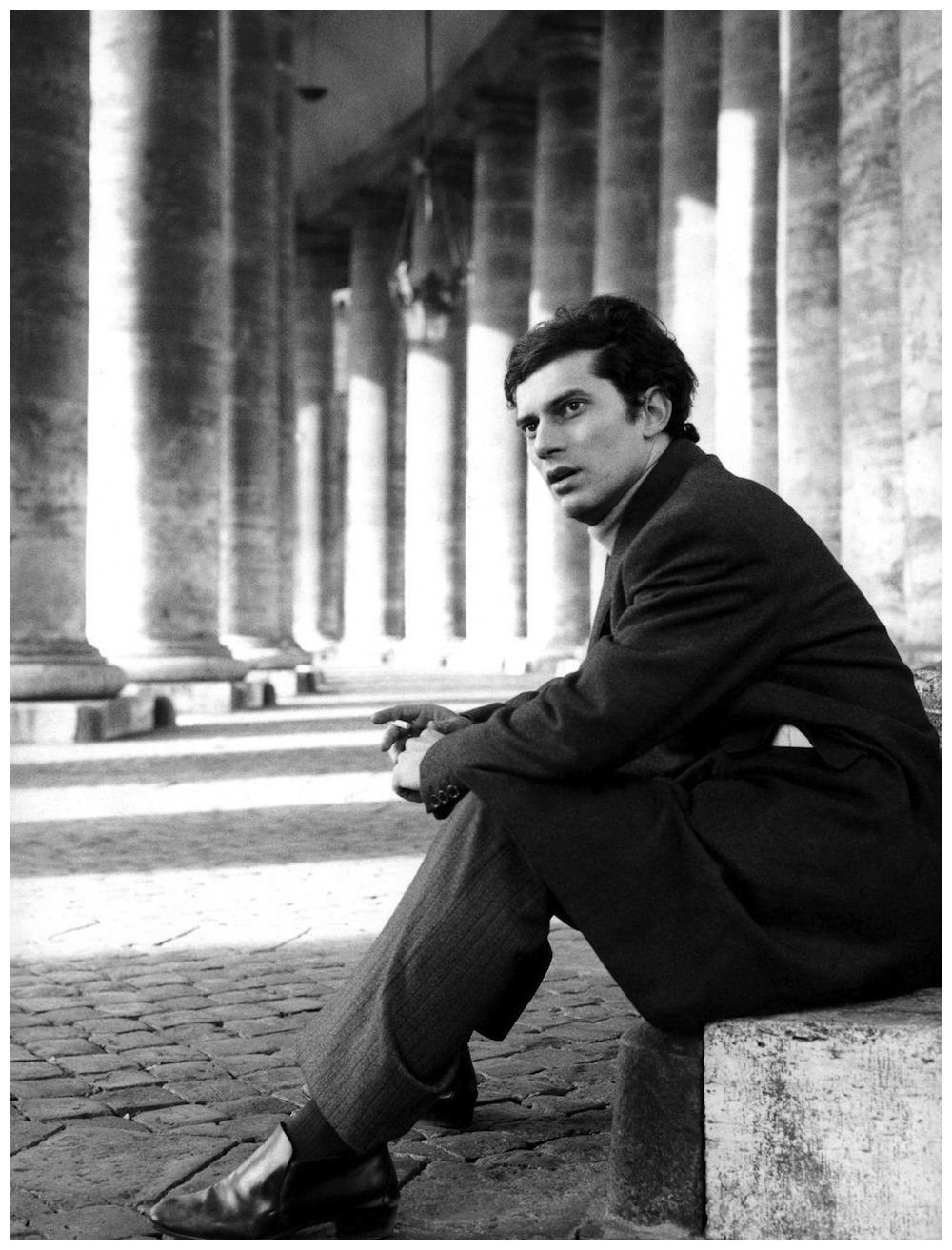

Prior to his C.P. Company years, Dalla had an interesting career mostly related to underground scenes. It’s the Sixties and the singer-songwriter’s look mirrors those of American beatniks and British CND anti-nuke pacifists. This style was dubbed hobo because it was surprisingly informal and rebellious for those days. Corduroy slacks, roll neck jumpers, button-down or flannel sports shirts, flat caps, berets: a bohemian fashion that influenced, also ideologically, troubadour Luigi Tenco among others.

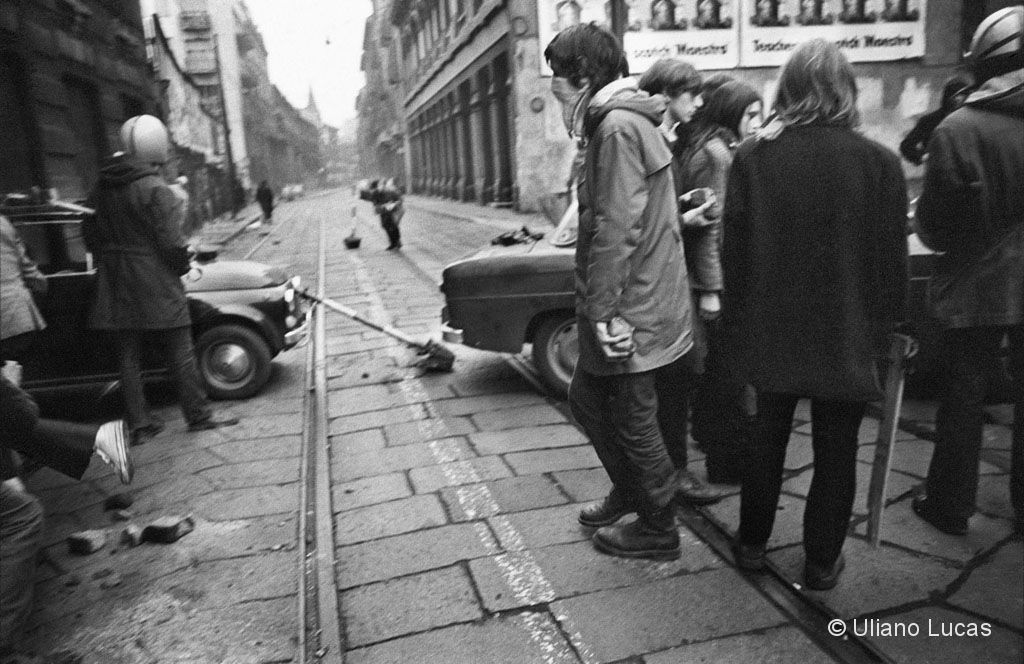

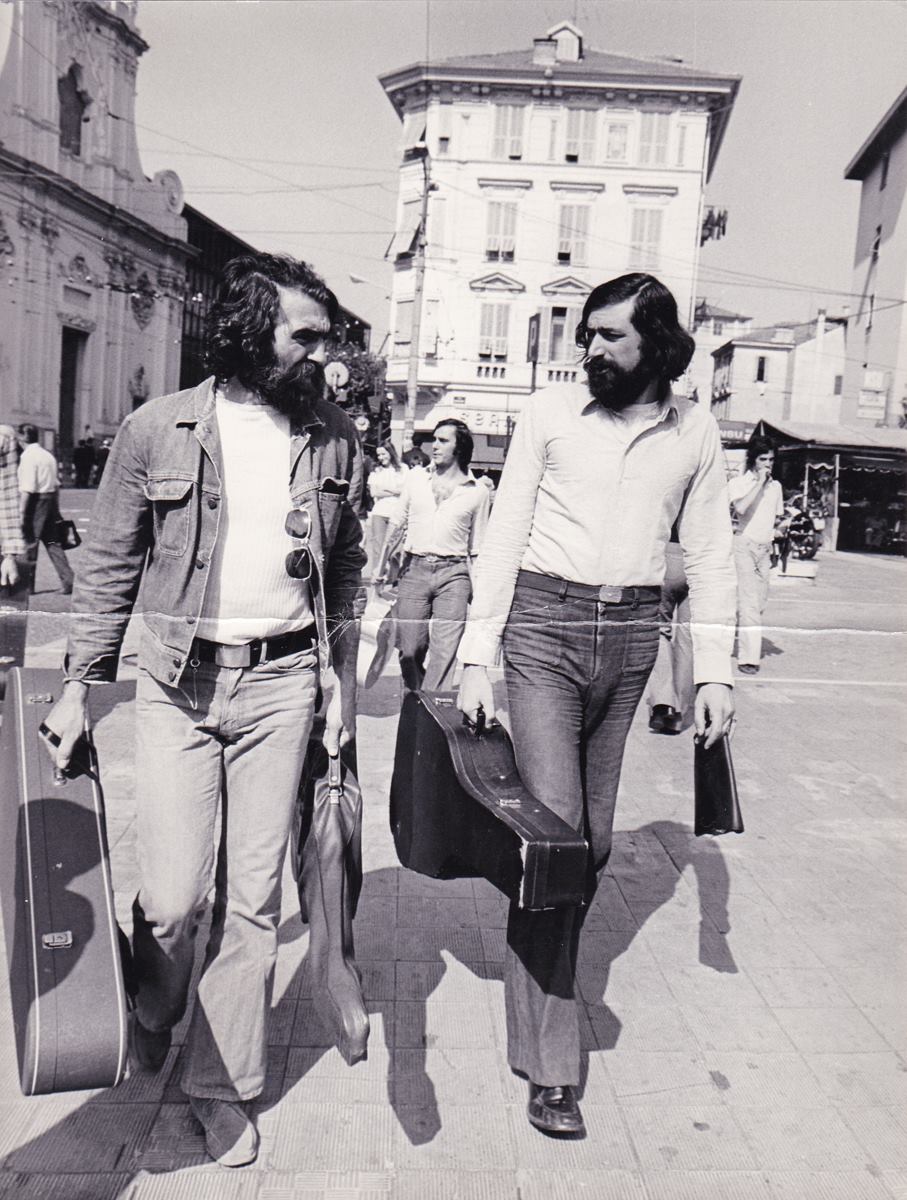

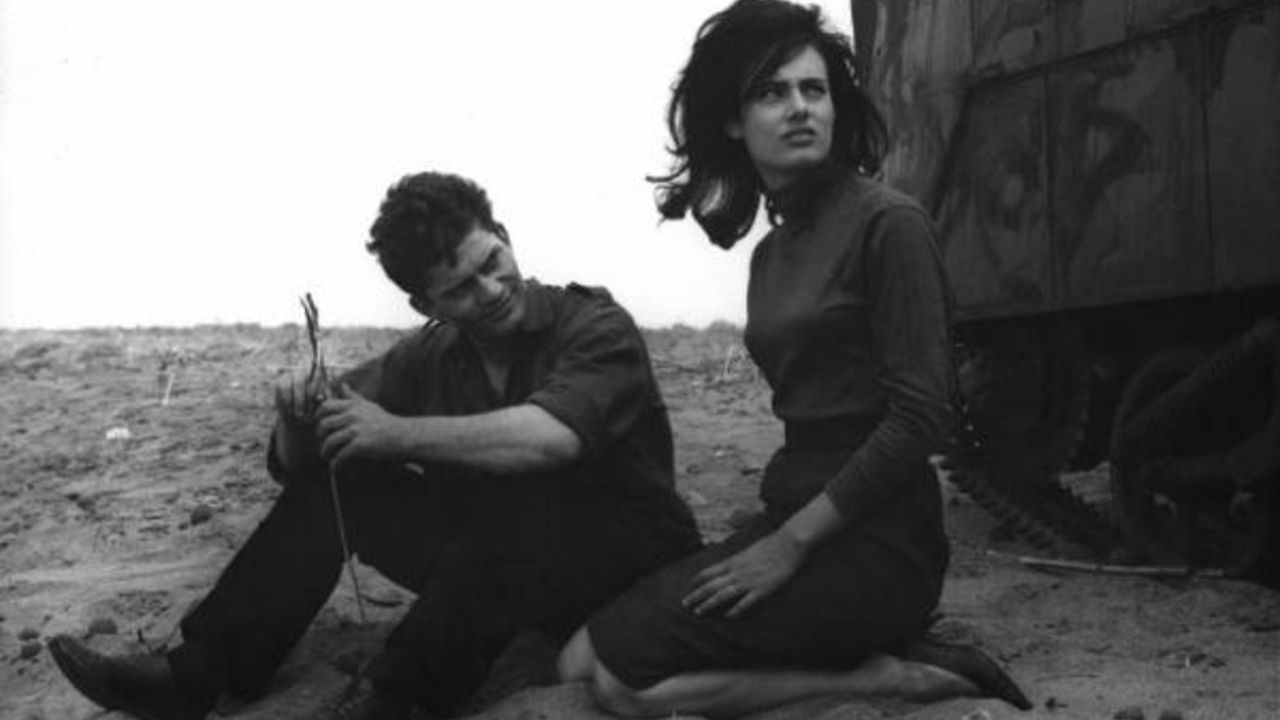

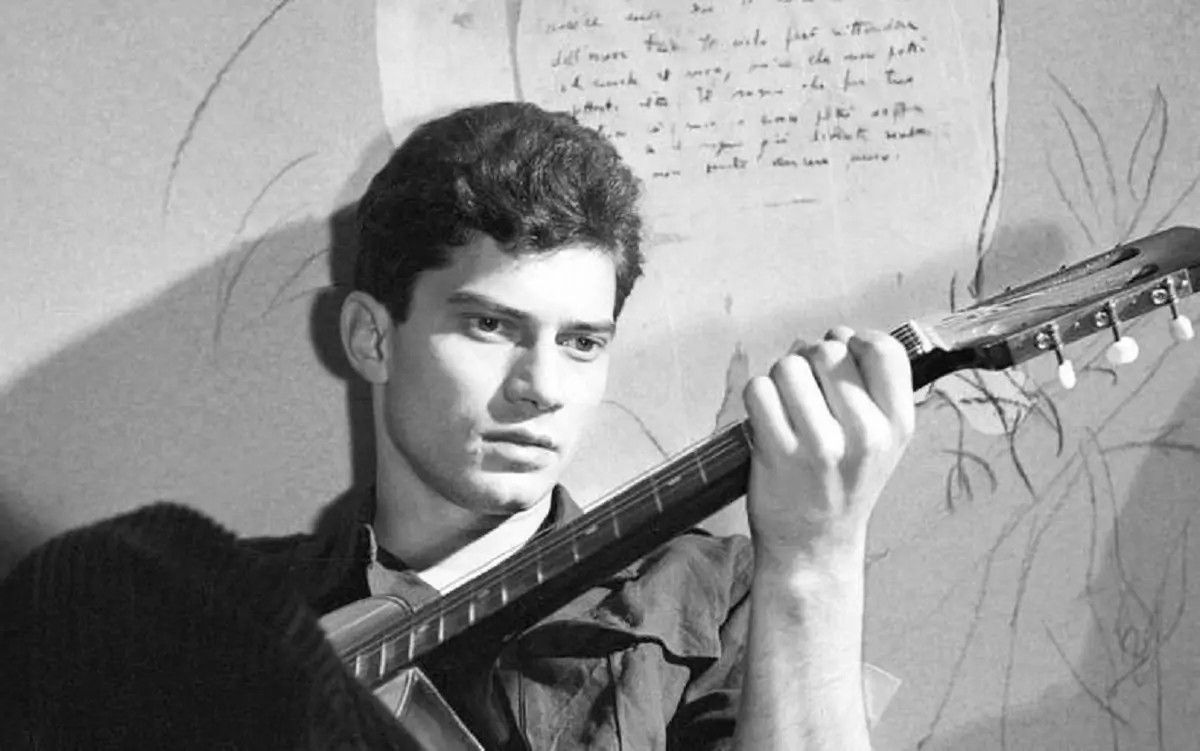

This style soon spread among students who, yesterday like today, always influence the aesthetic canons of their times. Those are the years of youth contestation, when political rallies and armed protests became the new norm. As a consequence, armywear, worn with provocative anti-militarist connotations, rose in popularity, also thanks to the ease of finding affordable pieces in surplus stores and markets. One of these garments were army shirts. Luigi Tenco was one of its first ambassadors, as witnessed by his role in Luciano Salce’s film La Cuccagna, where he interprets the semi-autobiographical role of a bohemian and pacifist troubadour. Over the years, on top of becoming a consistent part of casualwear, army shirts were adopted also by the likes of Fabrizio De André, Ron, and Edoardo Bennato, on top of also becoming a staple of post-punk aesthetics.

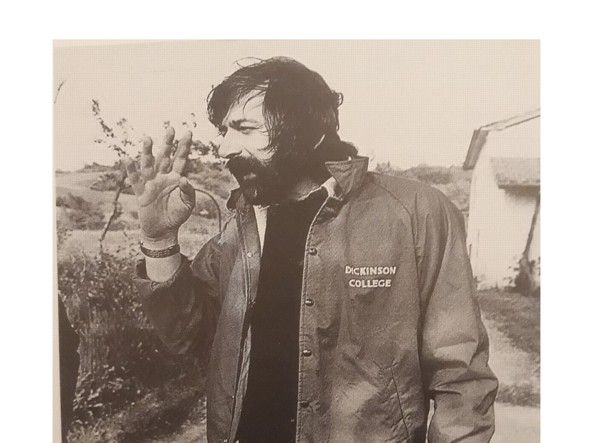

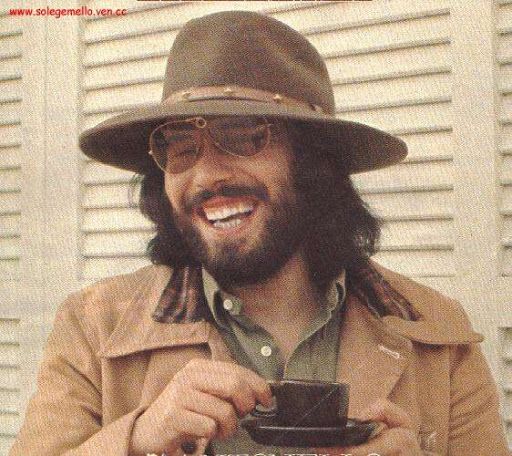

Armywear thus becomes an example of how practical needs - however recurring, from the aesthetics of black blocs to that of BLM - and linked, also economically, to vintage fashion can contribute to defining generational aesthetic phenomena. Examples include the field jackets of the Italian army – our own version of the famous US Army M-65 jacket – which depopulates both stadium curves and political demonstrations, and the eskimo. It is precisely the latter that becomes, especially thanks to Francesco Guccini, emblem of the political singer-songwriter, in a very close relationship between the public and the artist sealed above all through the sharing of clothing.

De André & knitwear

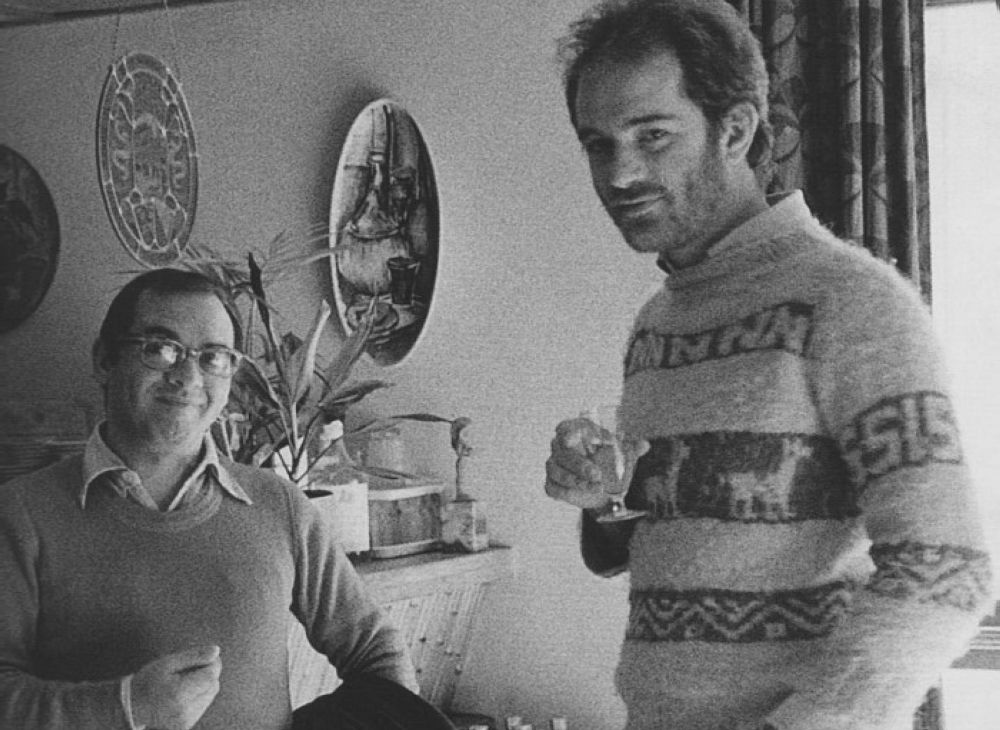

Being the cantautorato a genre born in the fields of folk and characterized by a strong fanbase of students and intellectuals, it has always dodged the opulence of fashion, anticipating much of casualwear in the years to come. Stages par excellence in which the singer-songwriter of the time makes his eyes look and in turn influences the language of streetwear are rai studios of varieties and programs such as Discoring and Italian Swiss Radio. In the color concerts hosted by the RSI between 1981 and 1982 you can see a sober Endrigo singing without a tie aging his image as well as how the synthesizers renew his classics, and Roberto Vecchioni in a flamboyant pink crew neck sweater. As if to suggest that the focus of the cantautorale narrative is inherent in words more than aesthetic vezzi, knitwear dominates.

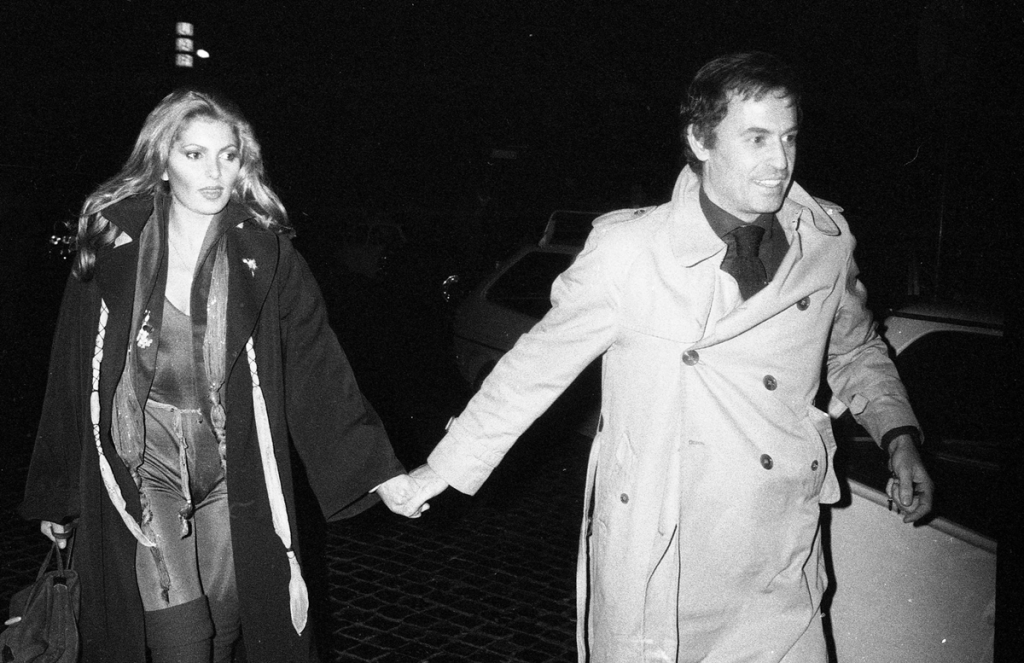

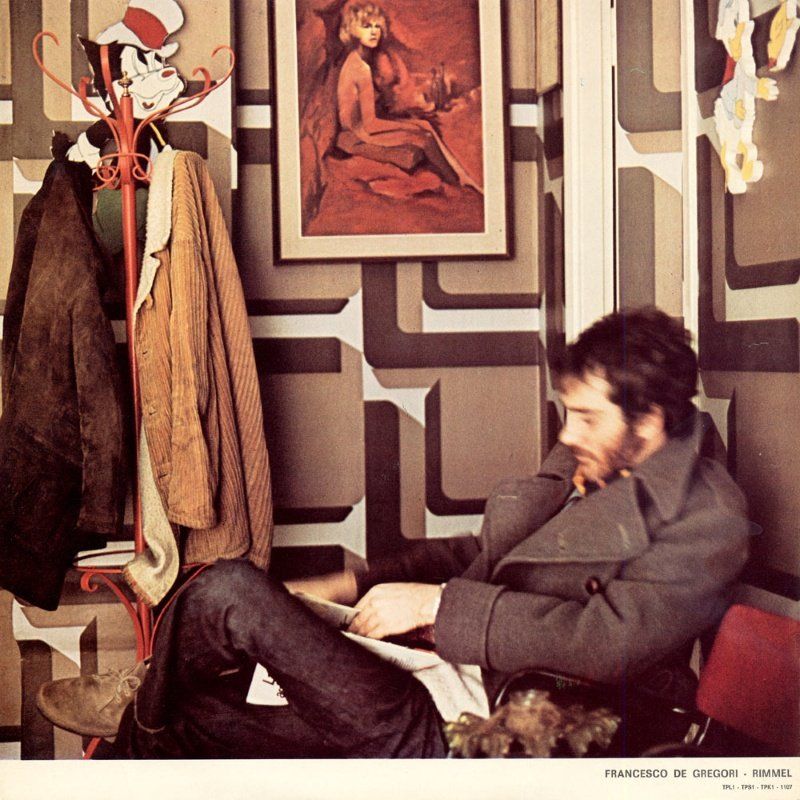

Whether it's the slim fits of the Seventies combined with a convex collar gown, or those baggy with Missoni-style patterned textures, sweaters and cardigans have been classics of Italian pop artists for years. In addition to Bruno Lauzi, Tenco, Battisti and Guccini, De André is among those who in his long career makes the most use of it, in an evolution of cuts that follow those of his music: first drier, then colorful and folkloristic with Creuza de Ma. It is no coincidence that the recent revival of the 80s songwriting style, has made us witness a plethora of artists - from Calcutta to Fulminacci, passing through Giorgio Poi and Galeffi - wearing this type of knitwear, both vintage and non-vintage. Perfect for sporty looks, knitwear finds an ideal partner in the long sand-colored trench coats that become a must of the period, from the police films to the cover of Una Donna per Amico di Battisti, an icon of Italianness that, ironically, was made in London.

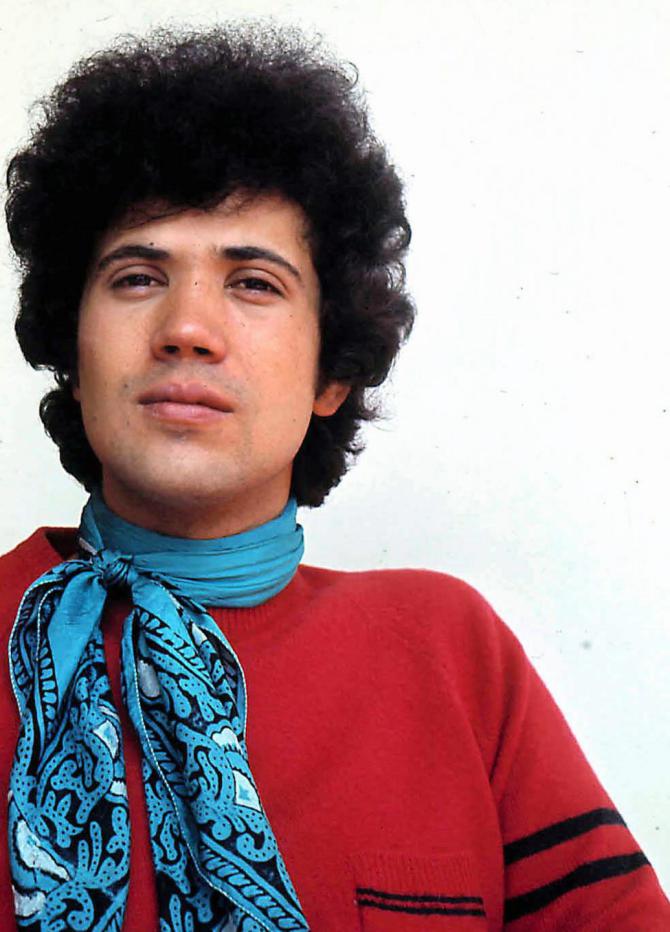

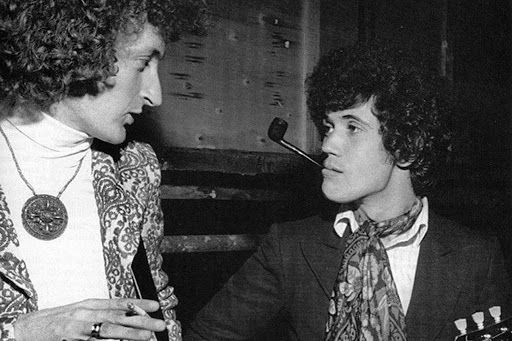

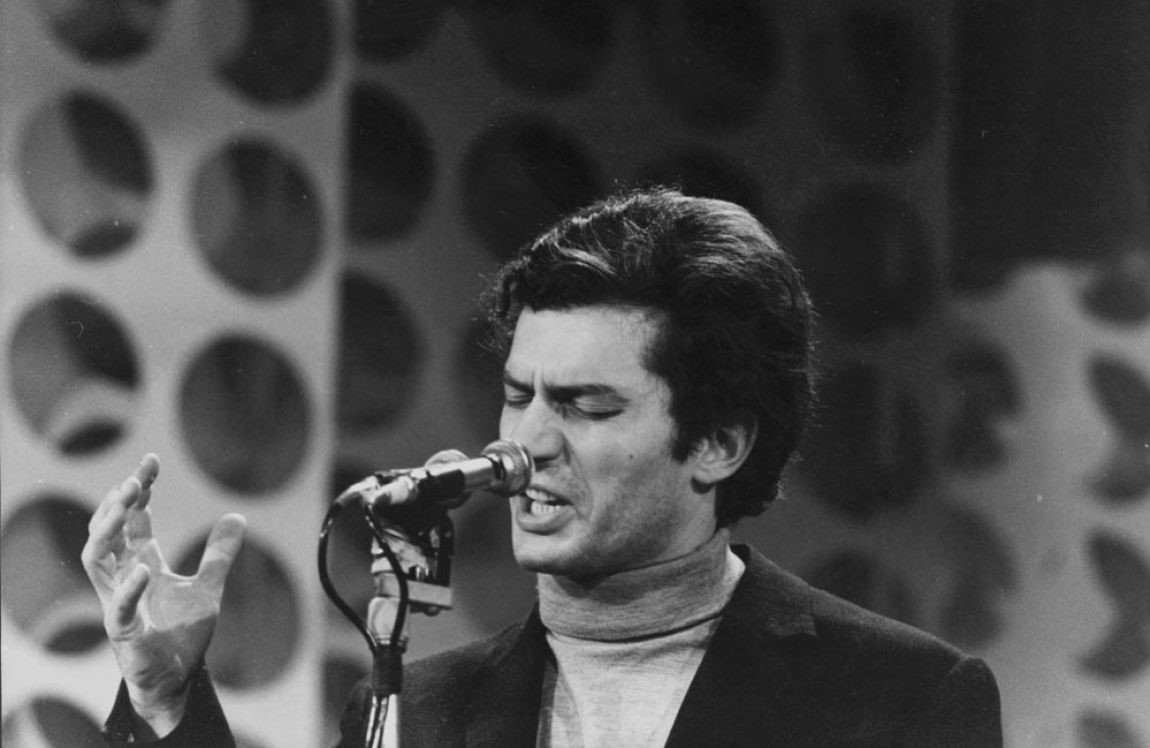

Lucio Battisti and the cravat

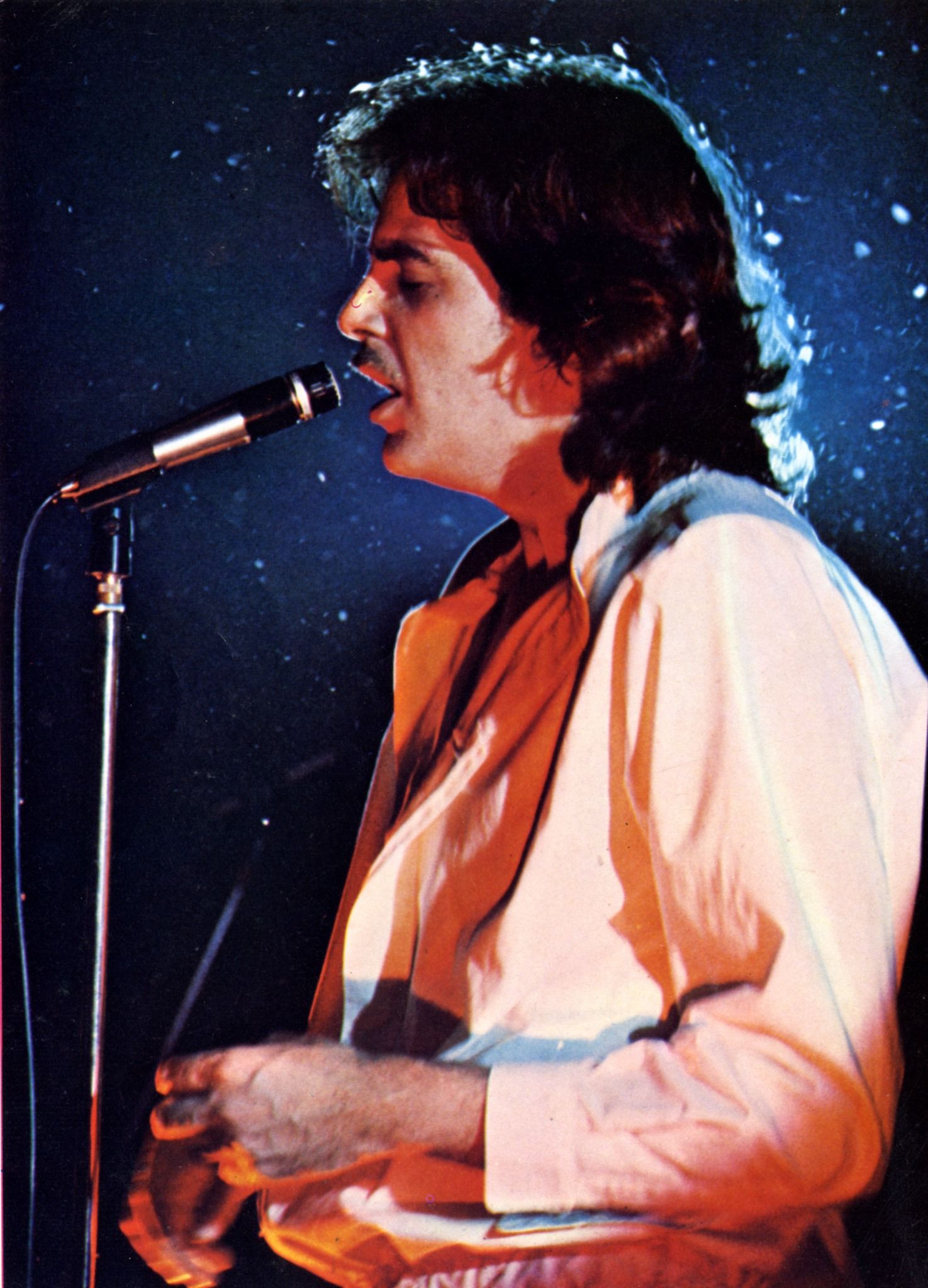

Lucio Battisti’s trademark, though, albeit in the first part of his career, is the cravat. Borrowed from psychedelic fashion, in the late ‘60 the use of the cravat extended to menswear and womenswear, becoming an accessory to be used with both suits, as an alternative to the ties, and with casual clothes. The cravat is an example of how different clusters can involuntarily interact, influencing each other by adopting aesthetic elements transversal to multiple scenes and social groups.

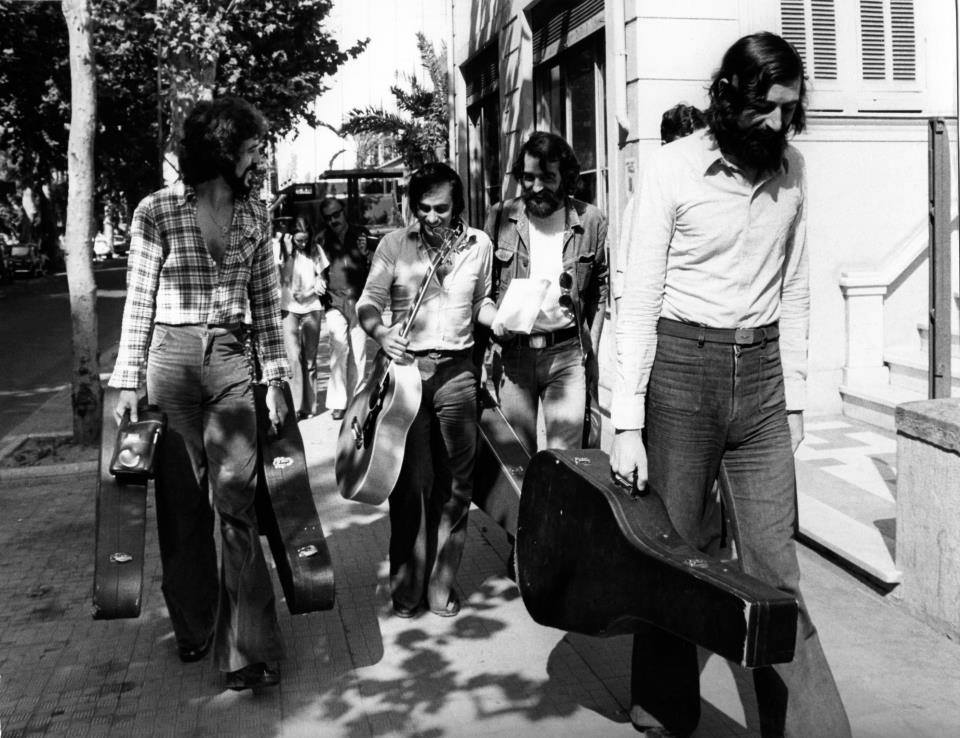

Denim, Suede and Sportswear

To seal the privileged relationship between many songwriters and casual fashion there is, without a doubt, the explosion of denim that since the 1970s has become a cornerstone of youth culture, both alternative and non-alternative. From the De André of the '80s that often shows itself in public with denim shirts under which you can see the Italian white health t-shirt, to Antonello Venditti or Banana Republic musicians who several times show off denim garments or in any case ascribed to the trucker aesthetic of the American West Coast; such as velvet jackets, rams, baseball or cowboy hats that echo De Gregori's 'Buffalo Bill'.

After all, with the passing of the years, the cantautorato becomes more and more pop at the expense of political commitment, pop like sportswear that towards the end of the Seventies takes on a new dimension in urban aesthetics under the influence of the American campus fashion. Lucio Dalla, a great lover of sport, is repeatedly immortalized with a series of uniforms including that of Virtus Bologna, the Chicago Cubs, and the Spring Valley, while in the filming of the docufilm Banana Republic De Gregori is filmed with a cubs cap

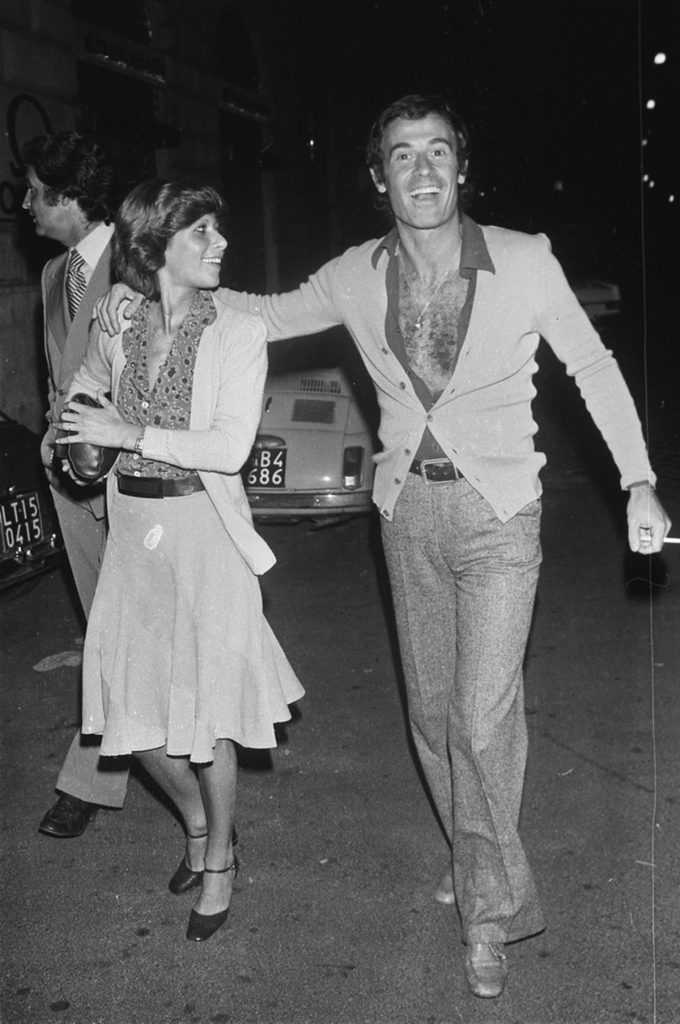

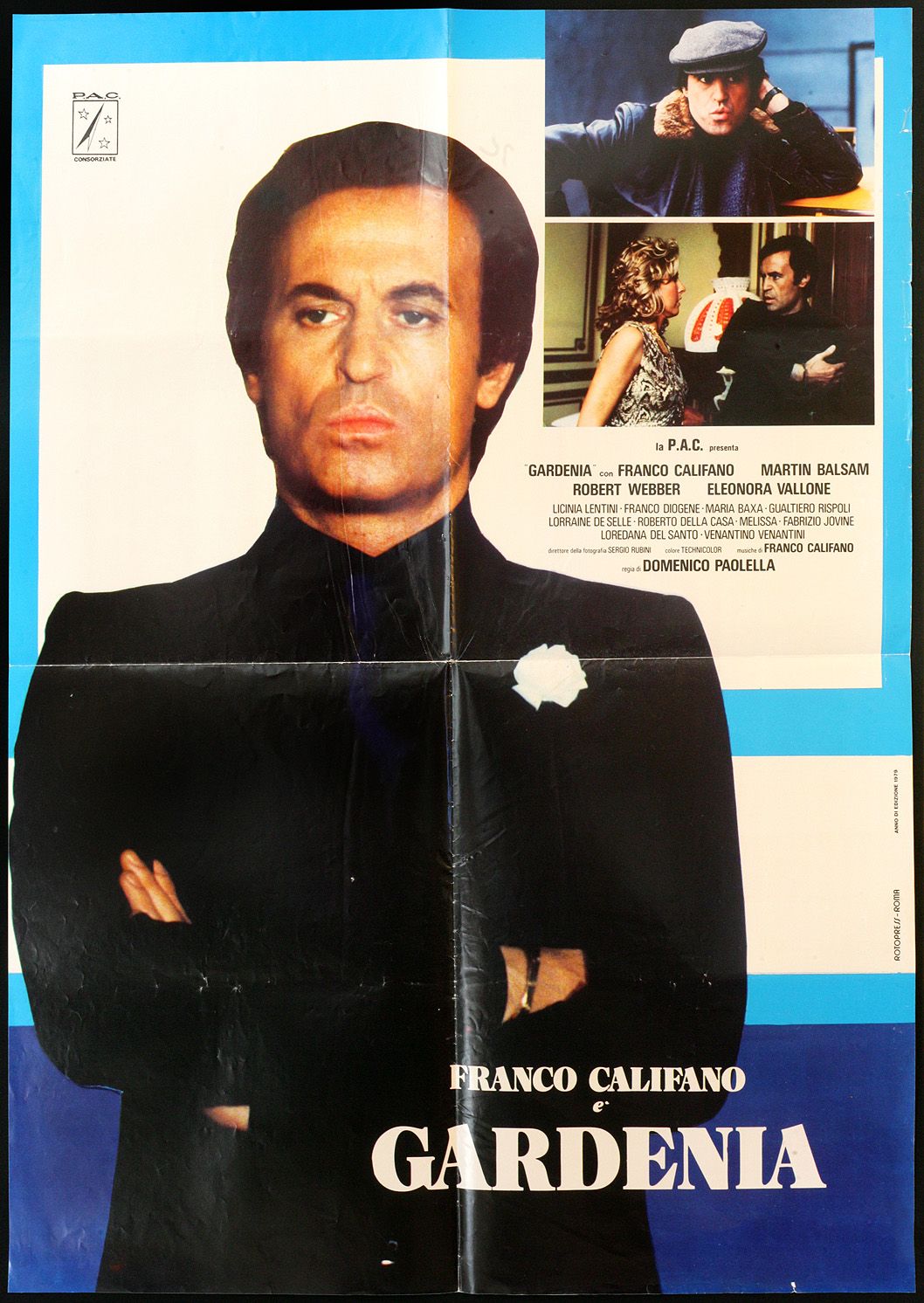

Califano, the biker and the dandy

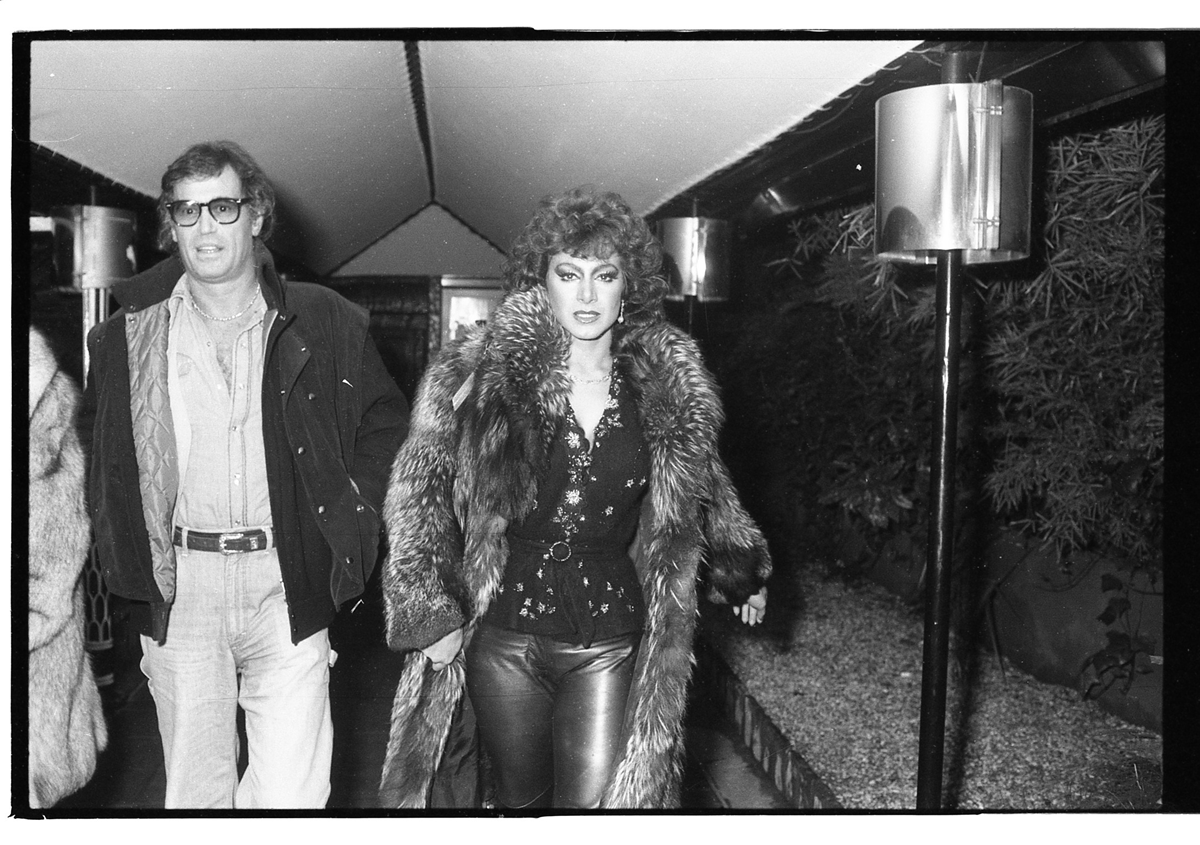

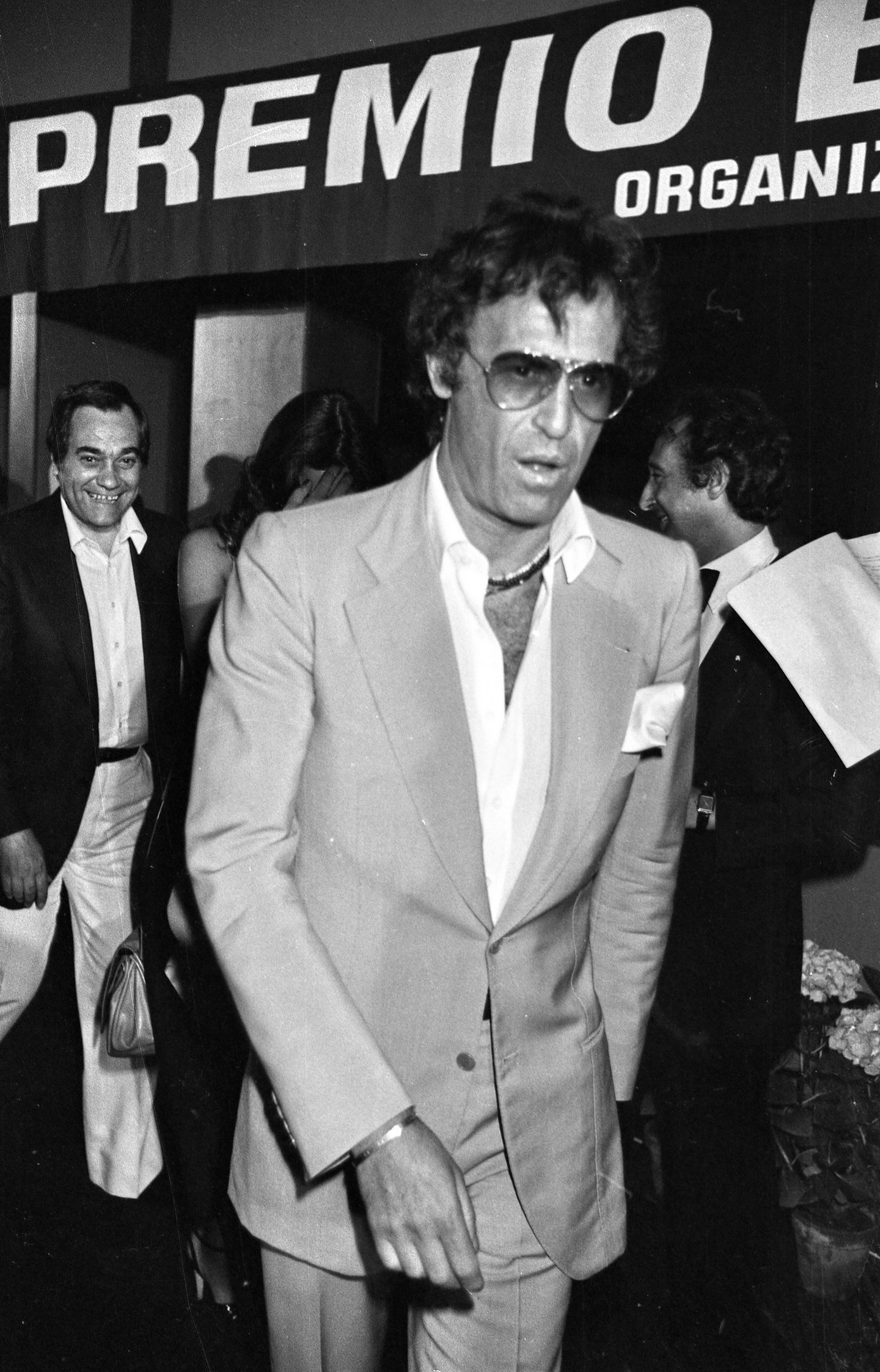

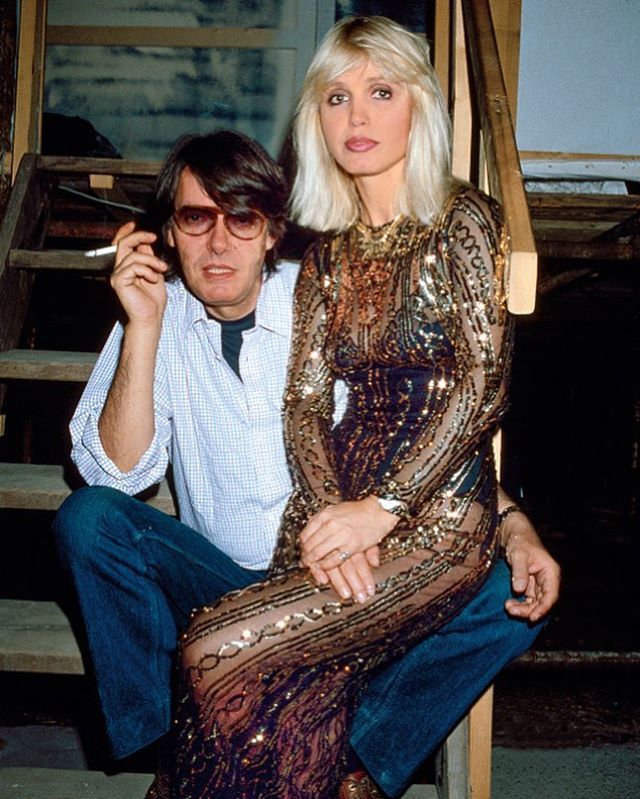

The Caliph [Franco Califano's nickname, ed] was also an admirer of double denim, often paired with leather boots and aviator-style sunglasses close to the looks of the late Elvis, Tony Joe White or Robert Redford. Outfits suitable for motorcycle racing, with jeans tightening the hot tanks and shirts strictly unbuttoned on the chest, where the ostension of jewelry and rosaries is inevitable – another must of the time that also involves Gino Paoli.

Califano, in addition to being a sensitive pen, was also a playboy and an aesthete, far from the song as a political instrument. His attitude is reflected in an elegant image also in the field of casualwear. Often immortalized outside nightclubs and nightclubs, the Caliph sports looks of neo-Gatsby and neo-gangster aesthetics that, under the influence of black music of the time, took hold in haute couture. Dresses in white colors and slender cuts, with trousers, jackets with wide revers and two-tone shoes in Roaring Twenties style. If the Caliph is the epitome of it in the 1978 film Gardenia, Julio Iglesias and, in part, Venditti and Dalla are also seduced by this style. On the contrary, the use of clothes by Franco Battiato is more desecral and characterized by the search for a deliberately normcore look, as a Middle Eastern employee or tourist, and characterized by gray and brown tones. Combined with a pigtail, the combo sandals with socks, and a rocking chair, Battiato's look in the early 1980s is as eclectic and spiritual as his music is.

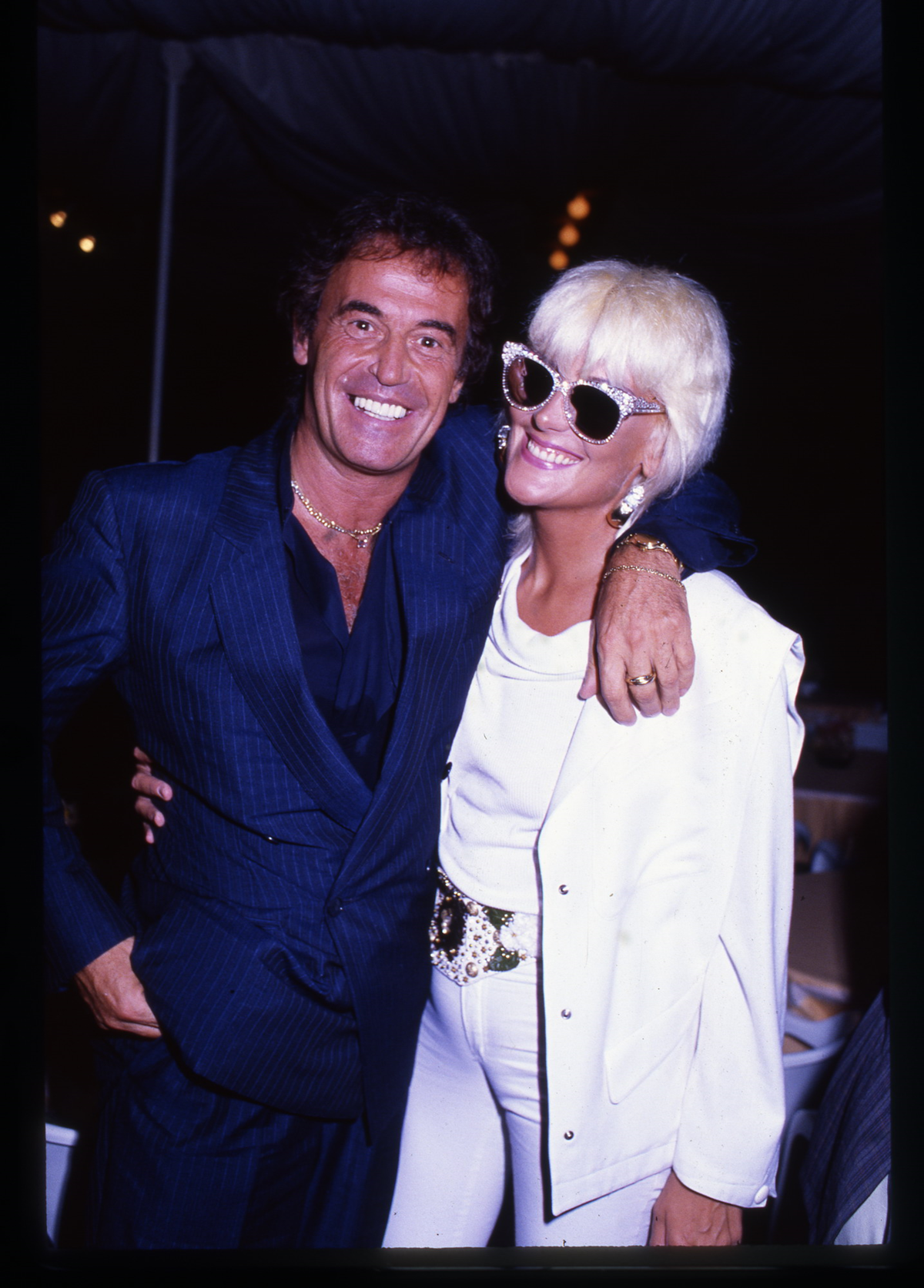

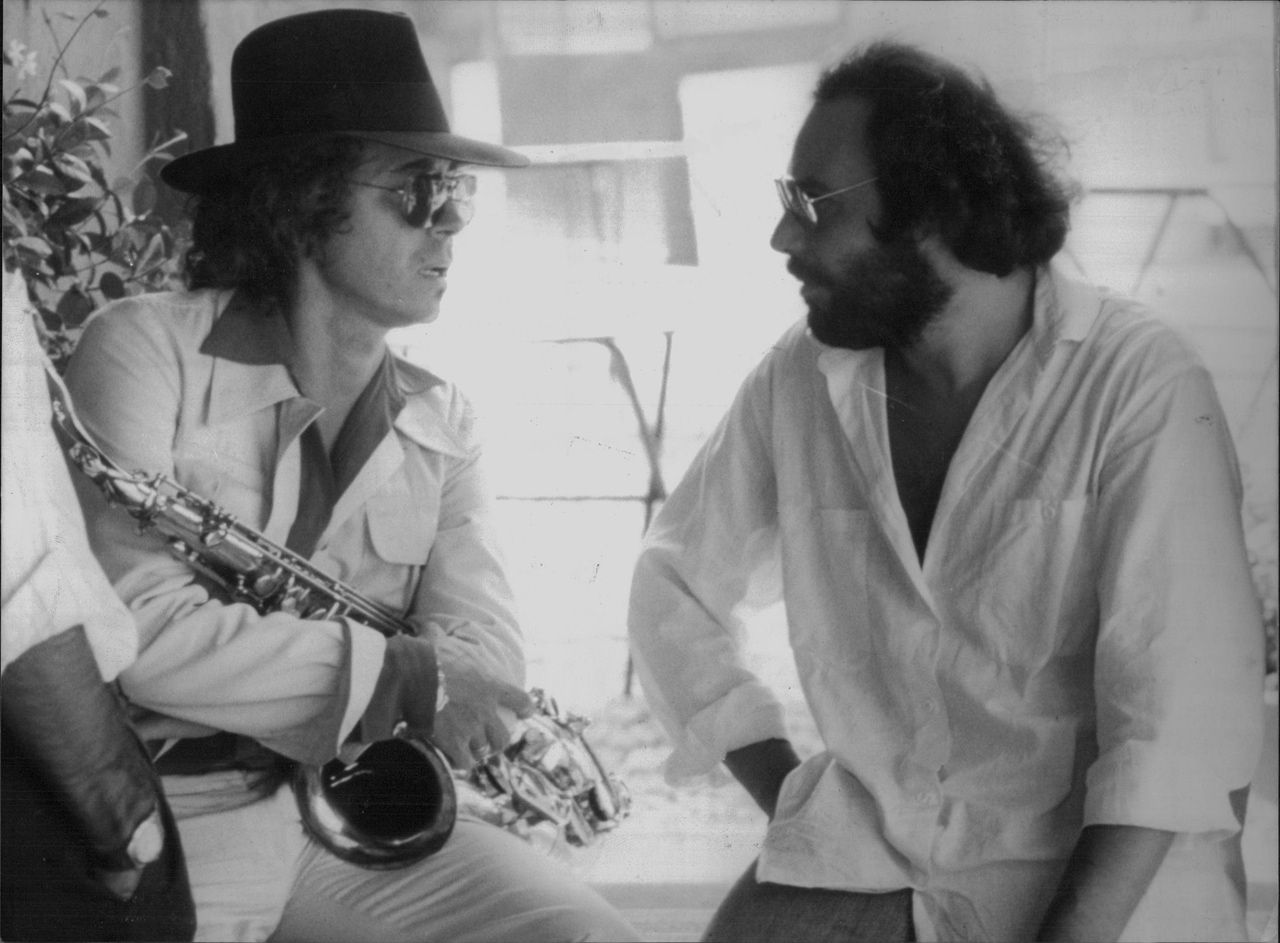

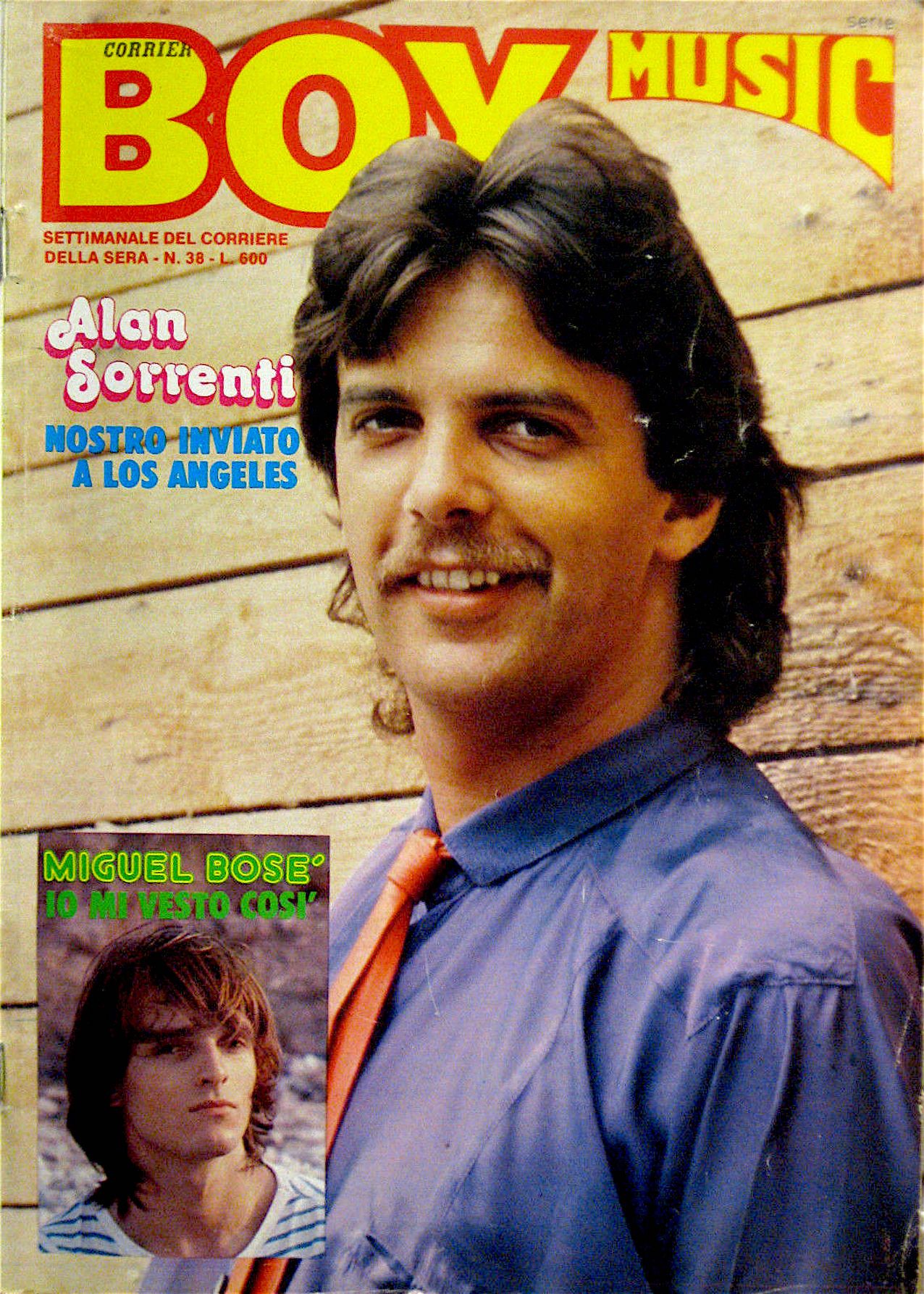

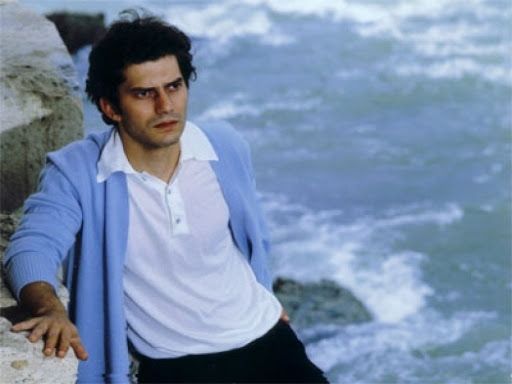

Carella, Sorrenti and the disco years

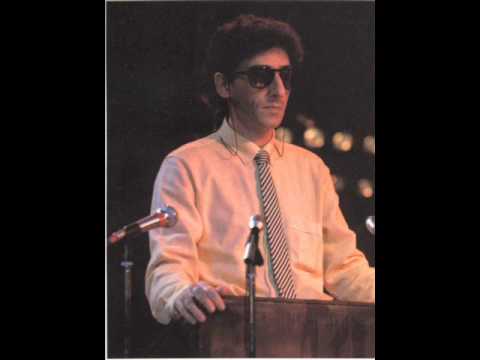

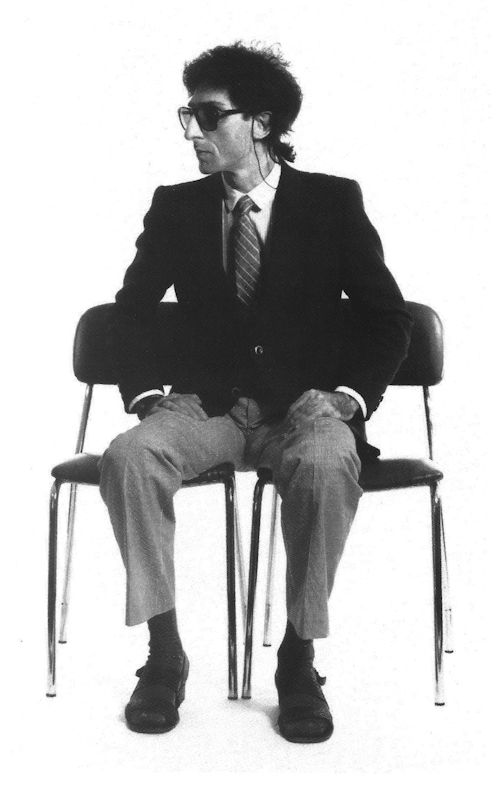

These soft cuts and their off-white palettes born on the Pacific axis between Miami and Tokyo, also spread in the boot going to exert an influence on the premises where disco music is asserting itself. Once again, a phenomenon of youth culture born in the context of clubs, flirts with the author's song, being appropriated by pop artists. The sagacious Enzo Carella shows off with outfits rich in tropical shirts suspended between the west coast of the United States and the discos of the Romagna Riviera, as well as Lucio Battisti who in 1980 shows up to sing Amore Mio Di Provincia at the German television in white trousers and exotic pink gown. Likewise Alan Sorrenti, who comes from a progressive and cantautorale past, thanks to disco music finds a way to the charts and a new wardrobe. Sorrenti makes soft suits with pinces in which total white dominate and pastel colors dominate his new uniform. Having disused the viveur clothes of the balere, Alan also gives us some sportswear peaks by showing up at a Tv Sorrisi & Canzoni party with an Adidas look halfway between a tennis player and a roller skater.

Although we can try to analyze with greatness the different aesthetic currents within the Italian cantautorato, it should not be forgotten that, being a markedly pop genre, the looks adopted by its protagonists were the dominant ones, although for this reason no less hip, than the Italy of the time. Therefore, the most common representation of the singer-songwriter at the turn of the 1970s and 1980s – save unicum such as Battiato or Dalla – will always be close to the look of the average man or boy of the time: trousers on the paw, velvet jacket, knitwear and shirt, with a fit oscillating between slim and baggy depending on the year in question. On the other hand, the cantautorato has been a faithful and truthful mirror of an entire country, from texts to outfits.