What does the acquisition by VF Corp mean for Supreme? Supreme is dead, long live Supreme

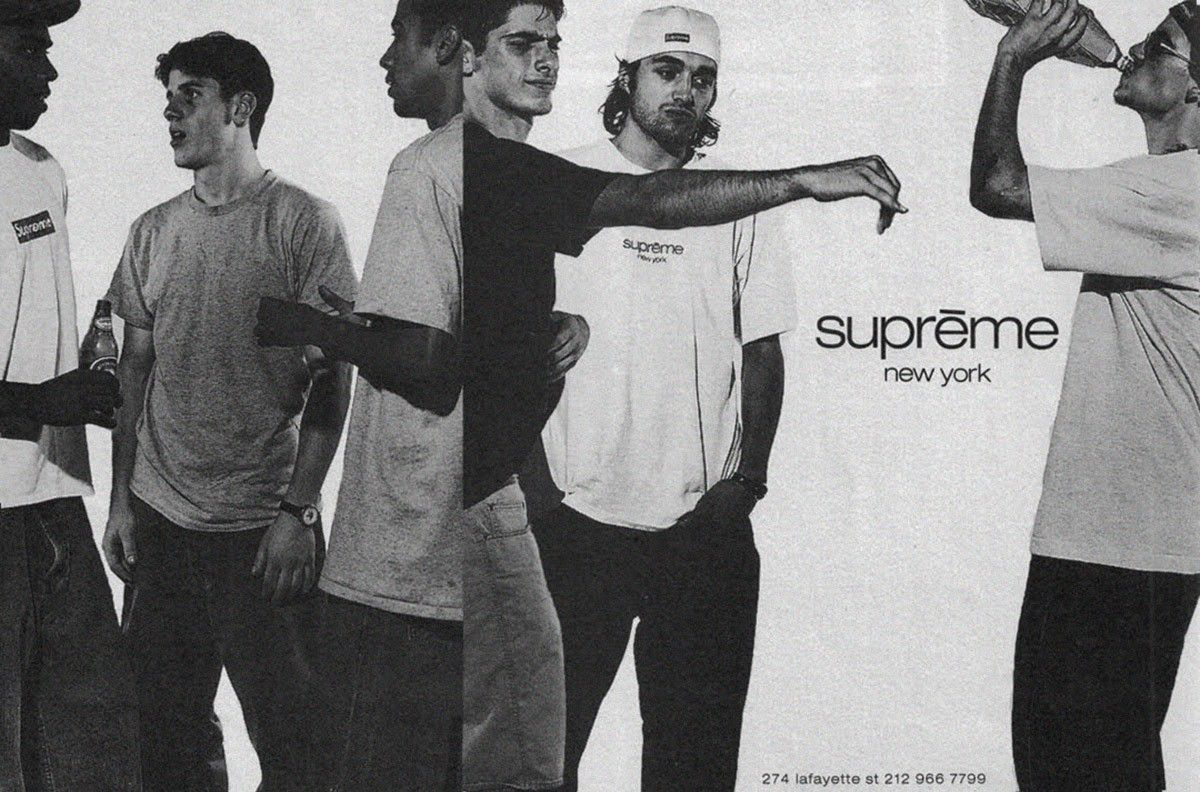

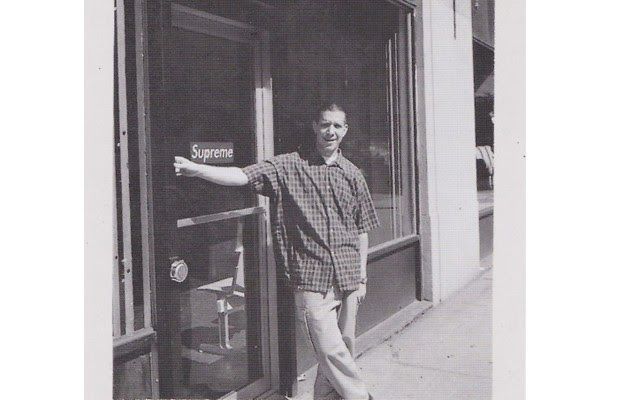

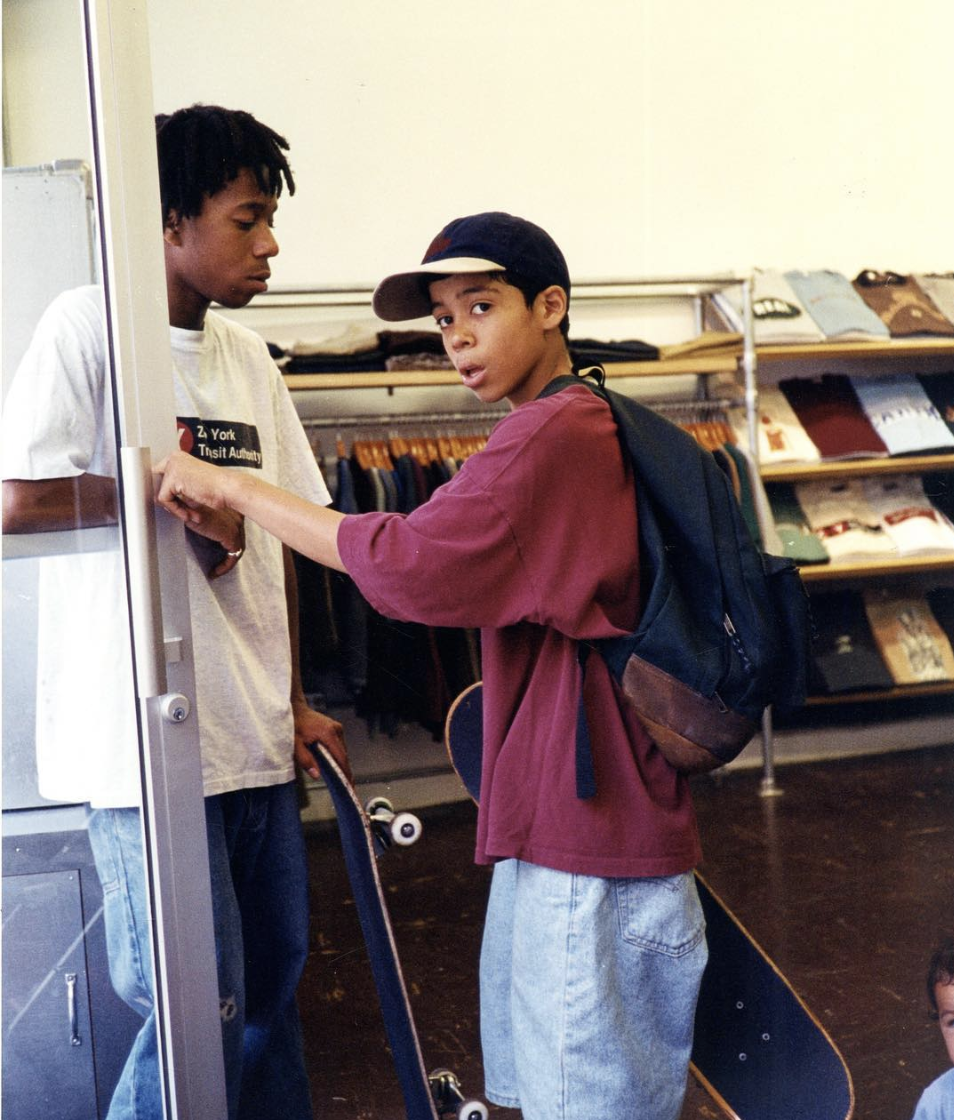

There was once independent streetwear. Small cult brands with a large following that operated within a specific culture. An era when the aesthetics of skaters were not copied: you were either a skater or not; just as New York aesthetics were not copied: either you lived in the big city or you didn't. Supreme was at that moment a legend – a brand so embedded in that colorful multi-cultural milieu that Larry Clark had photographed in his film Kids, a brand so true, real, connected to his world. Then came the hype, the culture of the New York niche diluted in a torrent of releases, multiplied in the dividends of a multinational and of that original spirit remained very little except perhaps excellent commercial performance. To the nostalgic it is easy to answer that things change, Supreme could not remain a store for skaters and at the same time the best marketing model of the last twenty years: what was born as a counterculture today has become The Culture. Supreme enters the first day of its new life: VF Corp has bought 100% of the brand worth $2.1 billion. What will happen beyond this point remains an unknown.

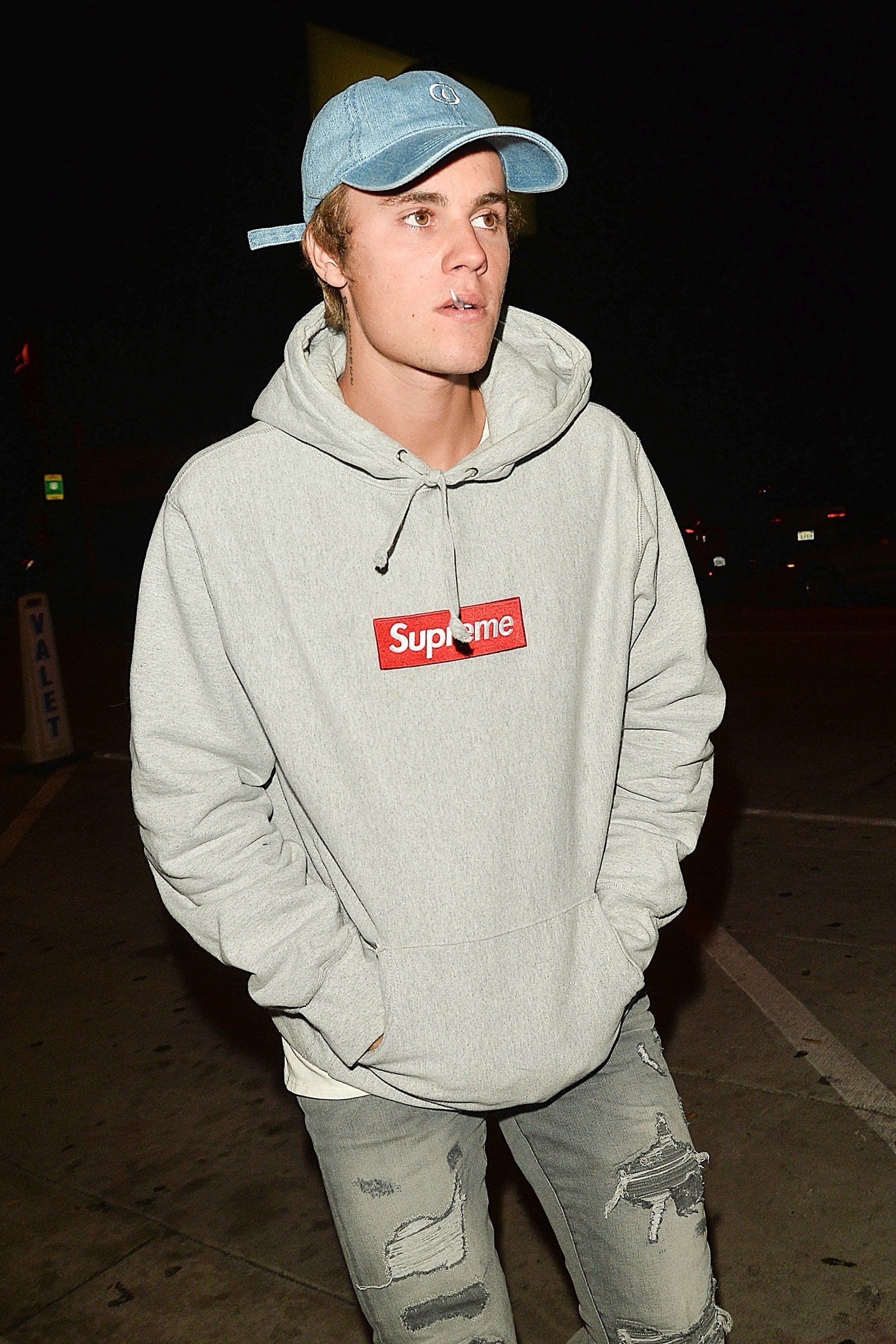

In the last twenty years all the brands in the world have wanted either to copy Supreme or collaborate with Supreme, trying to replicate or take advantage of its weekly release system based on the principle of scarcity. Until 2017 Supreme maintained its independence intact in a fashion that, in its luxury side, was dominated by large conglomerates and also on the sportswear side was controlled by the oligopoly of Nike, adidas and all the other historic brands. But in October 2017 half of the brand was bought for $500 million by The Carlyle Group – a sign that the too cool to care attitude of the brand and founder Jebbia was beginning to vane. The overall valuation is therefore 1 billion dollars, a non-sense figure for a brand that at the time had just 10 physical locations scattered around the world and an artificially low sales volume. Supreme's value lies in the immaterial dimensions: the coolness of a logo that has become a contemporary icon - as well as the subject of a legal dispute at the limits of the incredible - and the general coolness that surrounds the products, stores and even simply the Supreme name.

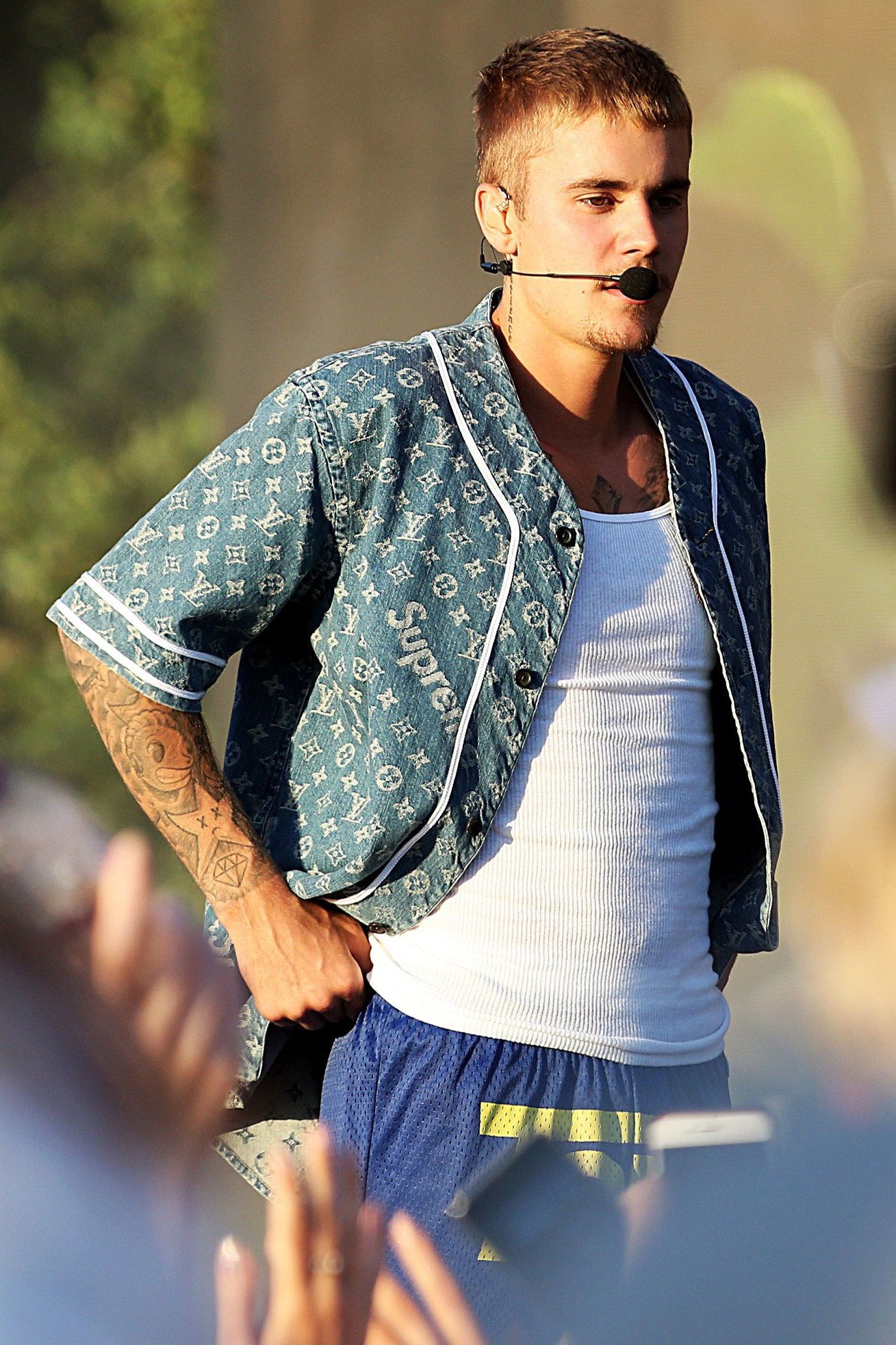

The Carlyle group behaved as expected: it bought the brand, developed the business model and resold after just three years at a value more than doubled. A non-trivial operation when you have such an anomalous business model on your hands where you do not operate on the normal variables of quantity and price. Carlyle's interregnum was the training for the transition under VF Corp – a company that is familiar to Supreme but whose commercial power lies more on the level of department store brands than in fashion or streetwear brands. VF Corp owns Vans, The North Face, Napapijri and Timberland: in short, its specialty is the mainstream, accessibility is its rule. Something a long way from what Supreme represented for the first 25 years of its history.

Are we facing the end of the Supreme era? Many - as happened in 2017 after Carlyle's announcement - announced the brand's death in tones of apocalypse but the truth is that the brand, commercially speaking, has never been so flourishing. And VF Corp doesn't seem too interested in interfering with the brand's creative department – but the real question is about the business plan and collaborations: Supreme has co-signed collections with both large and small brands, but it's doubtful that VF Corp will agree to partner with its direct competitors and perhaps more likely to push the accelerator on its portfolio brands. If Supreme still has its influence, in fact, this lies in its ability to elevate the other brands with which it collaborates to a state of pop culture coolness. Needless to say, an upcoming collaboration with Timberland has already appeared on Supreme's Instagram Story today. Even more needless to say, the brand's collaborations with Vans and The North Face may have enjoyed commercial success but are light years away from being the most memorable and representative of the cultural phenomenon that was Supreme.

There are three consequences that this acquisition could have in the long run. The first is to understand how Supreme's physical store policy will continue: many rumors claim that the brand had already for some time a strategy of openings in Europe (Milan in the first place) that today are obviously questioned by the pandemic. The second is a change in the release and commercial strategies not only of Supreme but of fashion more generally considered how many brands have followed in its footsteps so far. The third consequence could be the beginning of a new trend for the big conglomerates of the industry: acquiring more or less cult streetwear brands to diversify their portfolio and conquer new groups of young consumers, transforming collaborations from cultural events to commercial getaways to improve the sales of the other brands in their possession. Whatever happens, Supreme won't be the same from today. To know what comes next, you'll have to sit back and watch.