What is fashion’s creative mafia and why does it need to end ? Restrictions caused by the pandemic calls for the end of one of the industry’s most exclusive systems

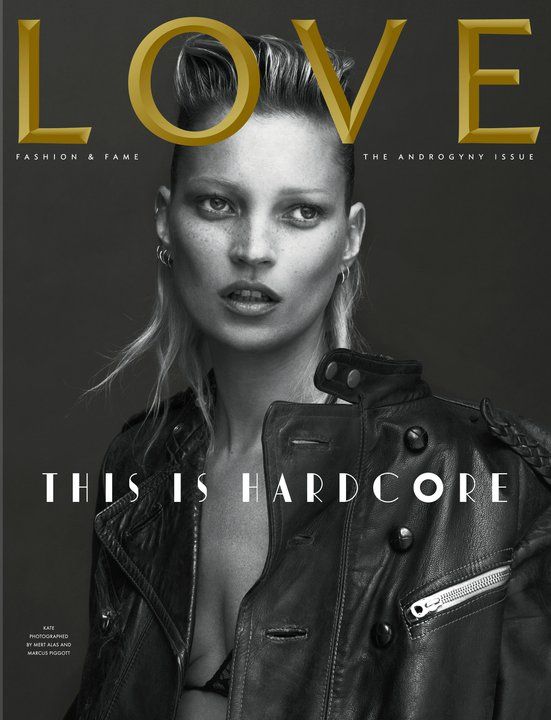

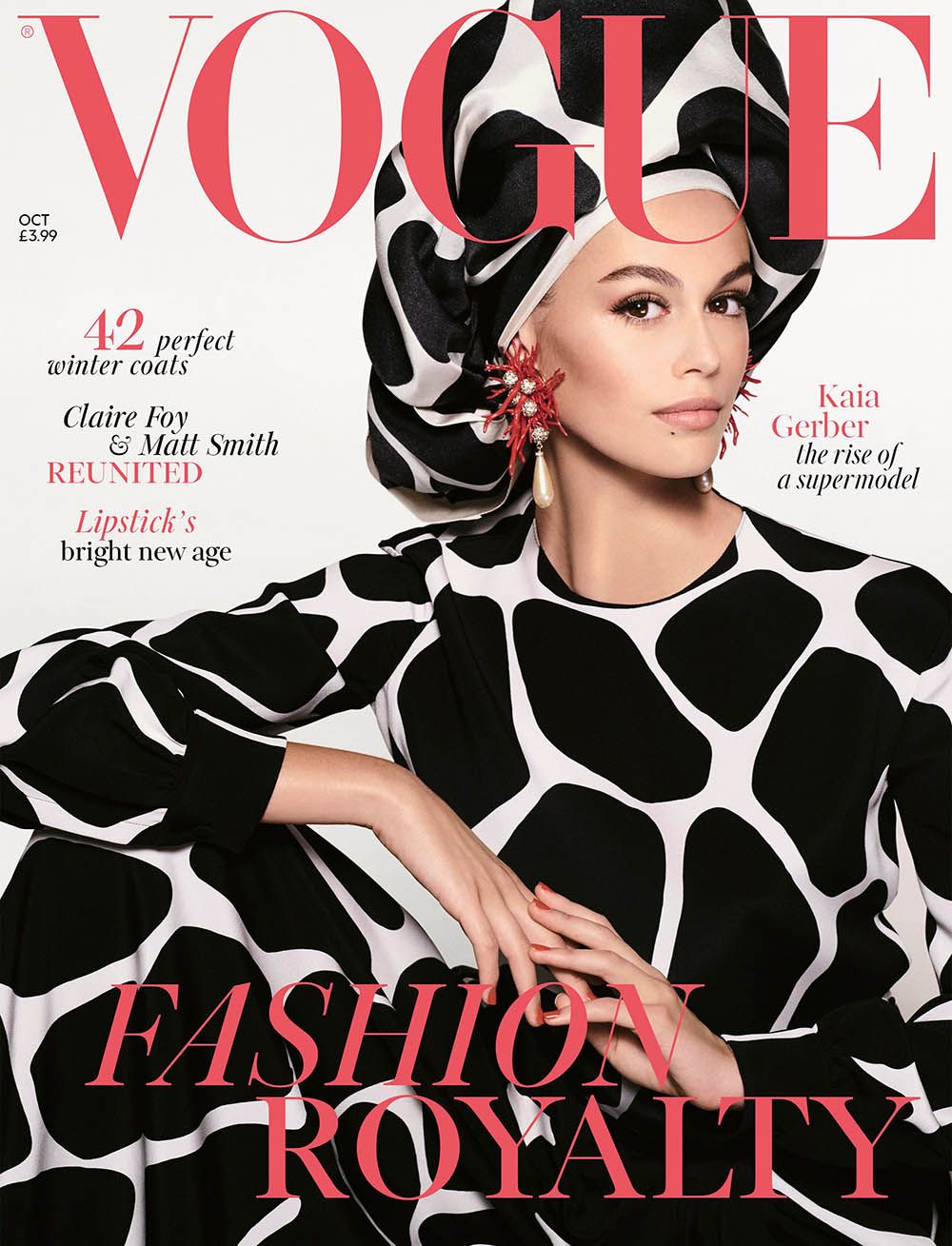

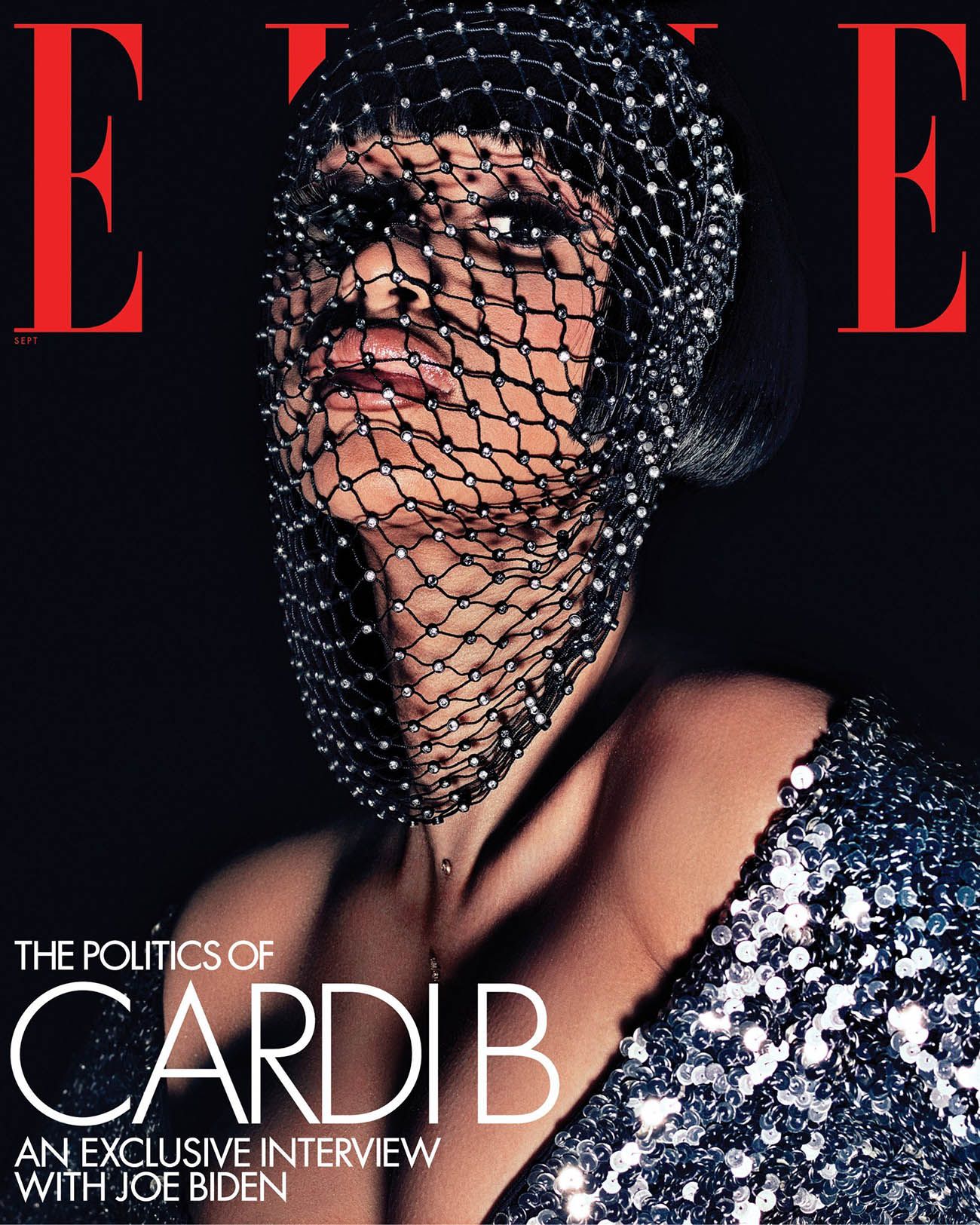

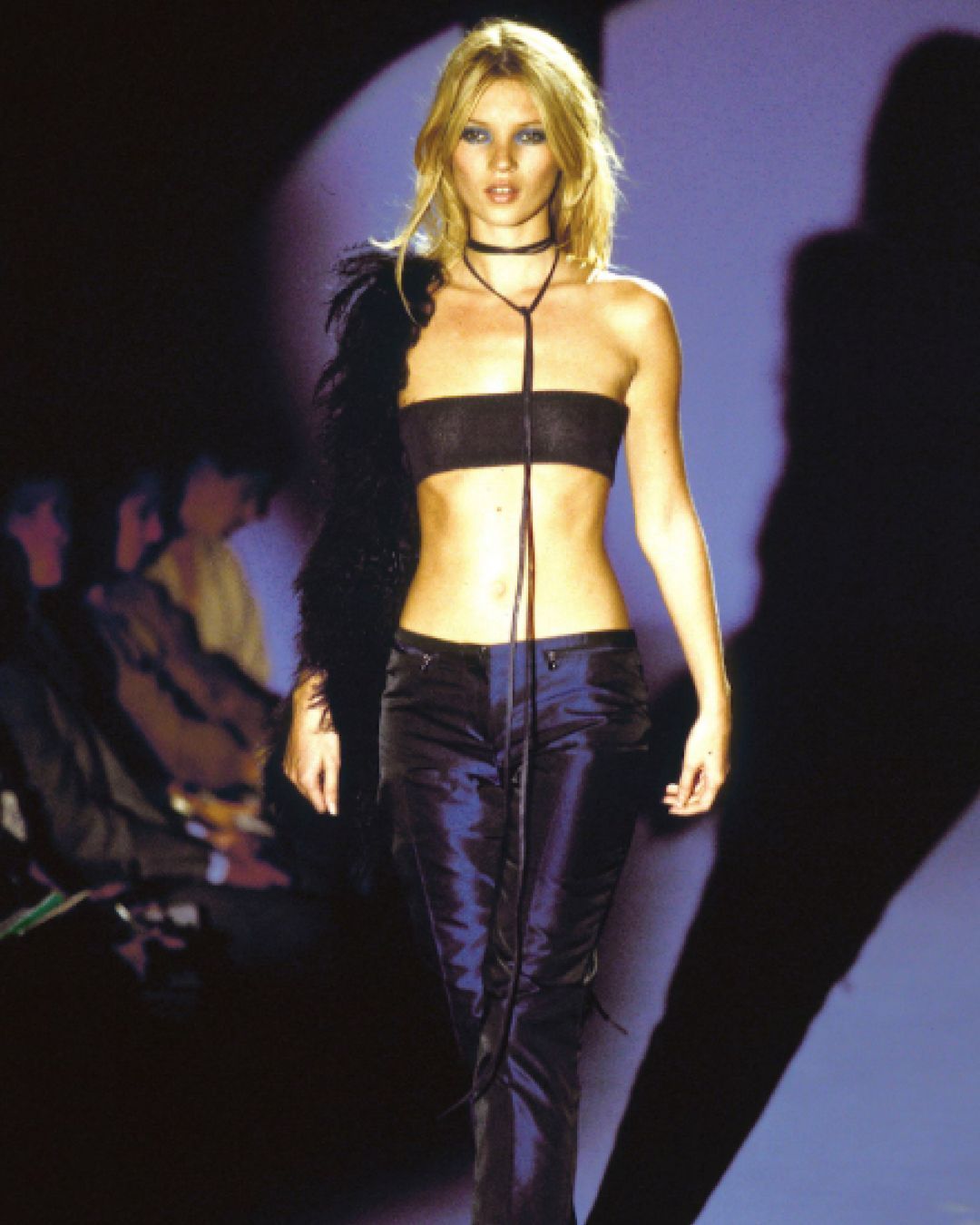

Throughout the past few years, if you were attentive enough and had collected a few issues of mainstream fashion magazines, you would have noticed a recurring pattern. Not in regards to the trendiness of the clothing being used but rather the names of the creatives that have appeared . Within the industry, through the pages of the Vogue’s , Harper’s Bazaars, Elle's and other top publications, as well as for the campaigns of big brands - a general pool of the same photographers, stylists and creative directors are often used to shoot covers and editorial content, which we have now come to define as the industry’s creative mafia.

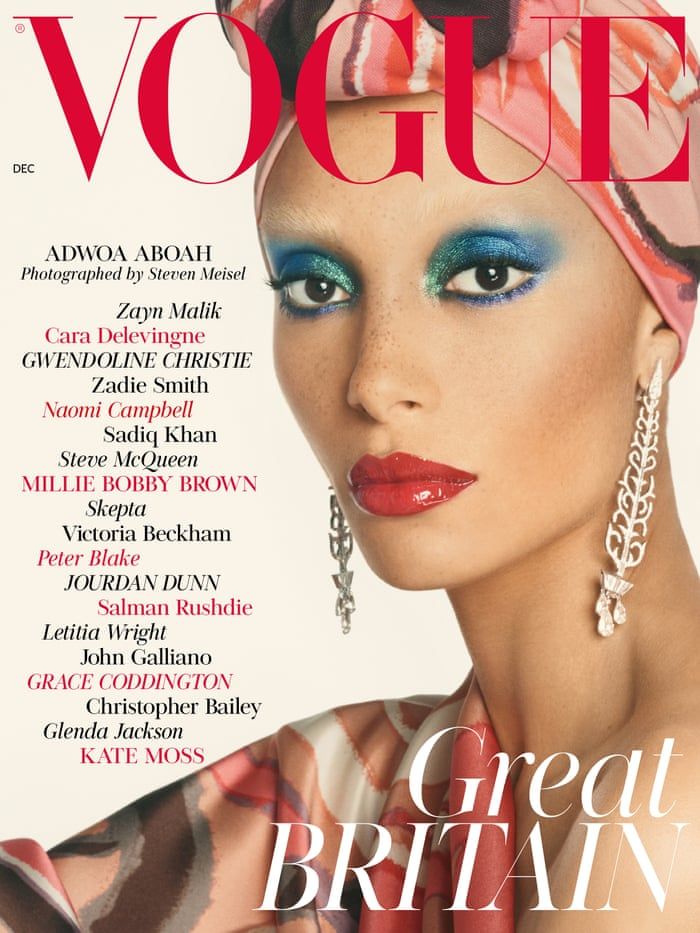

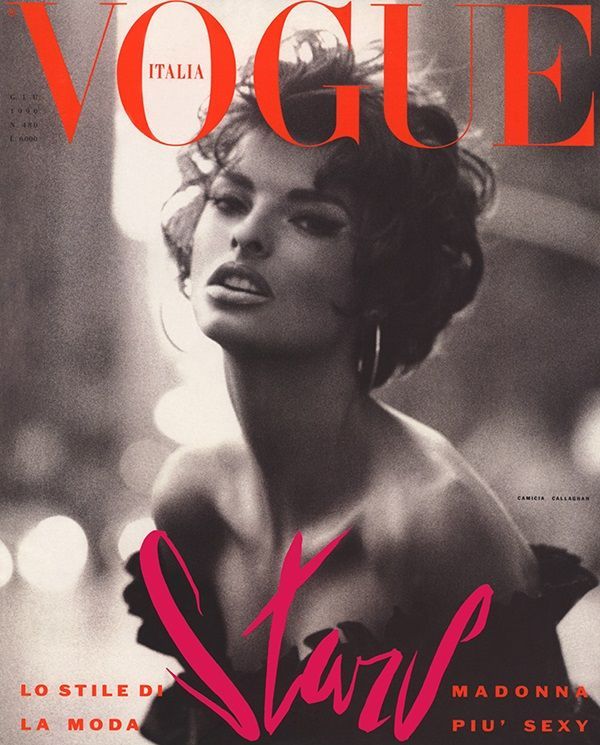

According to BOF, only 18 photographers have shot the cover of American Vogue in the last ten years — which means 120 covers were shot for one of the industry’s most prestigious magazine, and only 18 image makers have had the opportunity to do so and the worst part is, this doesn’t mean that number was equally divided. Photographers Steven Meisel has shot over 20 Vogue covers while the magazine’s first black cover photographer Tyler Mitchell has shot only three. This is not only the case with American Vogue but is an ongoing pattern across international Vogues, a number of other mainstream print magazines and luxury brands who often use the same pool of high profile creatives to shoot their campaigns.

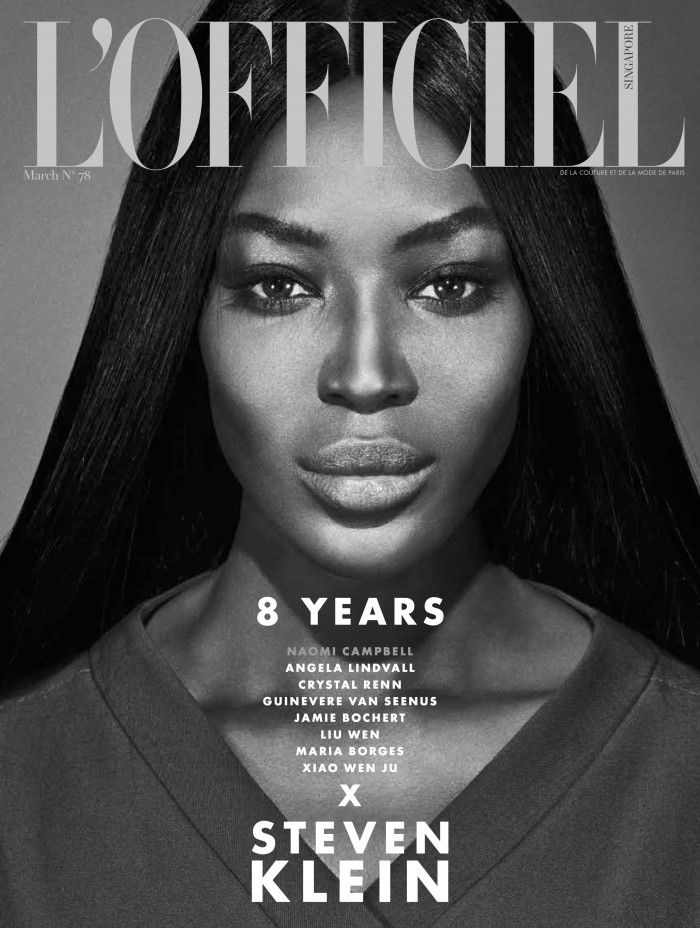

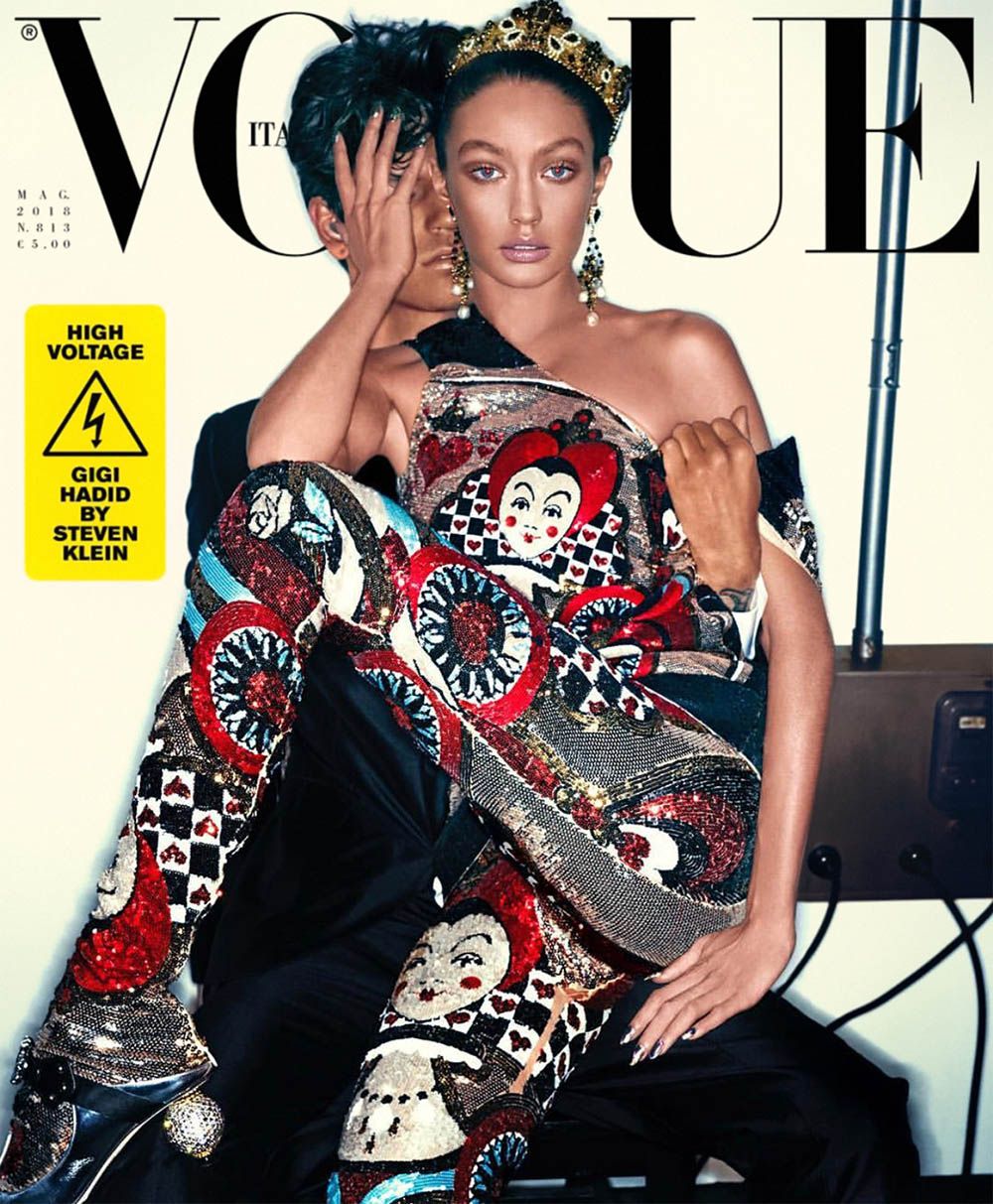

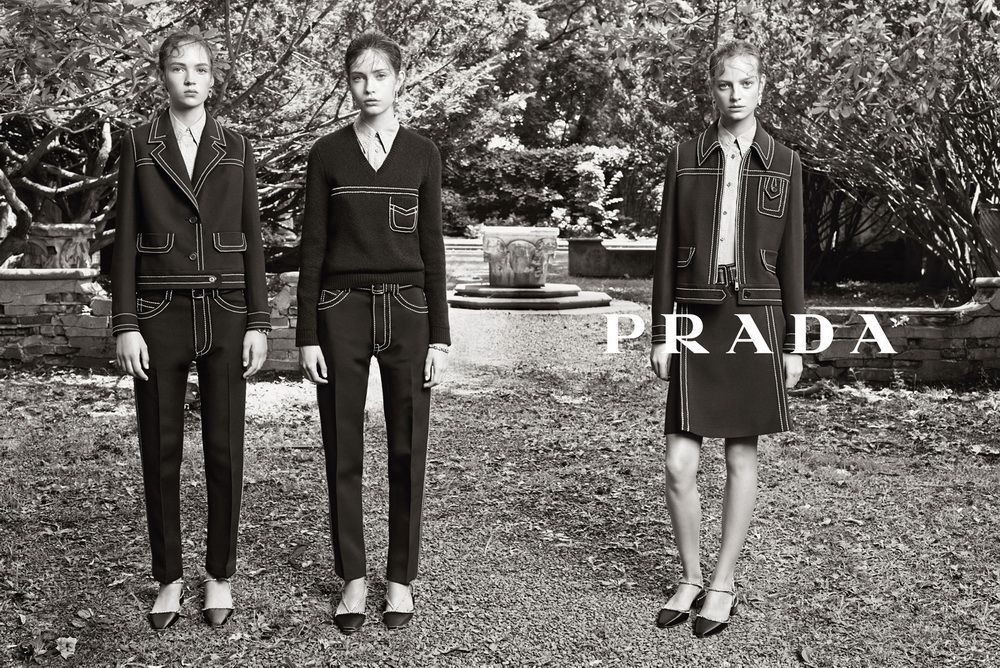

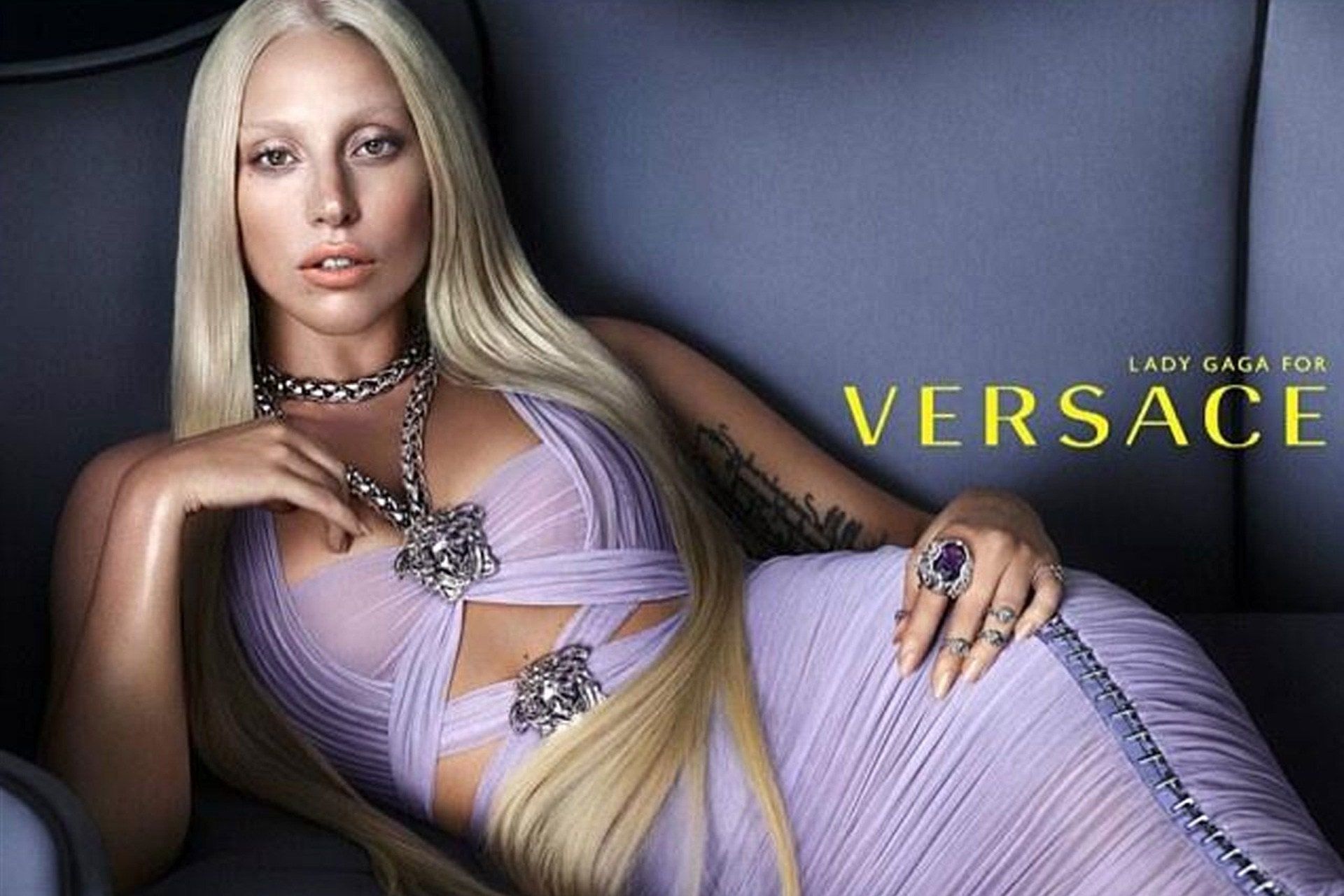

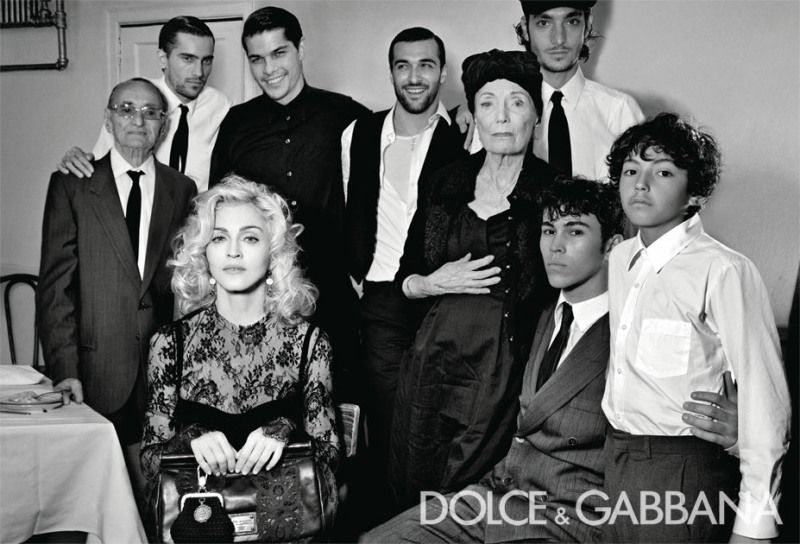

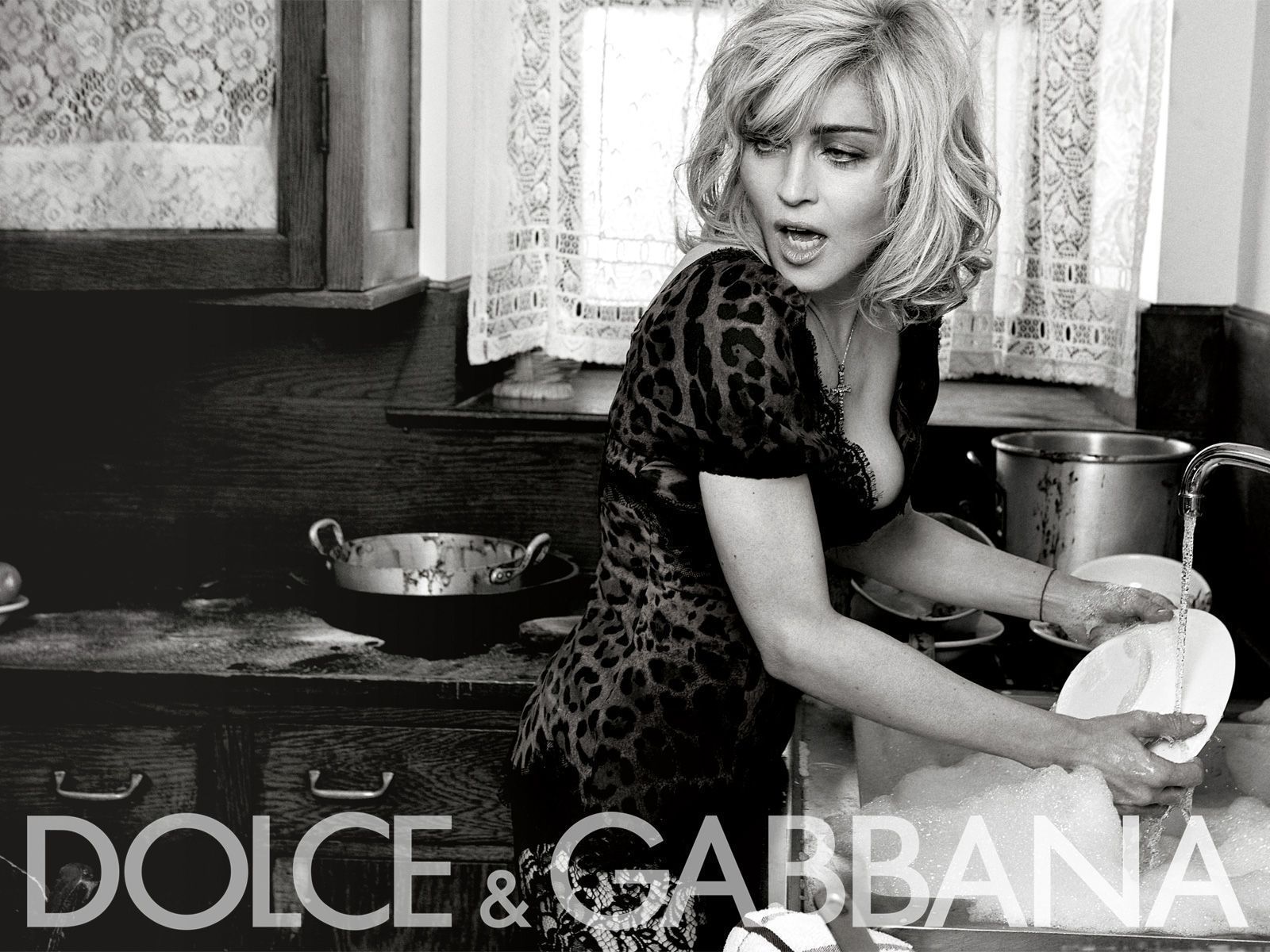

Of course it can be argued that the creatives in this mafia are somewhat gods of the industry who have earned their right to shoot multiple covers after years of hard work, and that is a fact that goes undisputed. Names like Steven Klein, Juergen Teller, Alasdair McLellan, Mario Testino and Mert & Marcus are people who have shot some of the most iconic campaigns for Prada, Tom Ford, Gucci and other big houses. However, the concern is how long the industry allows this godhood to last, the exclusivity of those who are let into it and the damage it does in existing. It is quite ironic because this is a system that does not apply for the creative directors of the major fashion houses as they change quite frequently, but for some reason each of these brands often pull from the same pool regardless of who their creative director is.

In hiring the same 20 people from the same circle for ten or more years, what it does is keep the money within the industry in the same place. It fills the pockets of big budget “in demand” creatives while younger up and coming creatives have to work for free or invest thousands of dollars in production to better their portfolios with the hope that the investment will eventually land them paid jobs. It has created a disproportionate system for the benefit of those in higher positions, while making the process of success ten times harder for younger creatives, and 20 times harder for young creatives of colour.

Fashion is a world that was originally built on selling the concept of exclusivity, and therefore insularity and nepotism are qualities that are nothing new to the industry. Be that as it may, in this new age where many throughout the industry swear by the pledge of diversity and inclusion, it is all except surprising that a circle like this still exists.

However according to the recent article by BOF, the restrictions of the pandemic might be the end of the industry’s elite creative gang. “When you open a magazine you see it’s always the same three photographers, always the same hair and makeup. I think that’s going to end with this pandemic. It’s about getting out of this mafia of always hiring the same people,” commented LVMH board member Antoine Arnault.

With restrictions of travel and lower budgets, brands and magazines are now being forced to source local talent instead of flying out their regular roster of creatives. This paired with the public pressures of the Black Lives Matter Movement to purge the industry’s racist practices to inspire change in creating more inclusive behind-the-scenes talent is slowly pushing towards the dispelling of the creative mafia. Ideally the goal would not be to take away the godhood from those who are already a part of this collective but rather to create an environment where this distinction is much more easily available to minority talents, does not take a decade to earn and does not cost creatives a fortune to create.