COS in crisis? Three reasons: a weak approach to digital, creative stagnation and lack of diversity

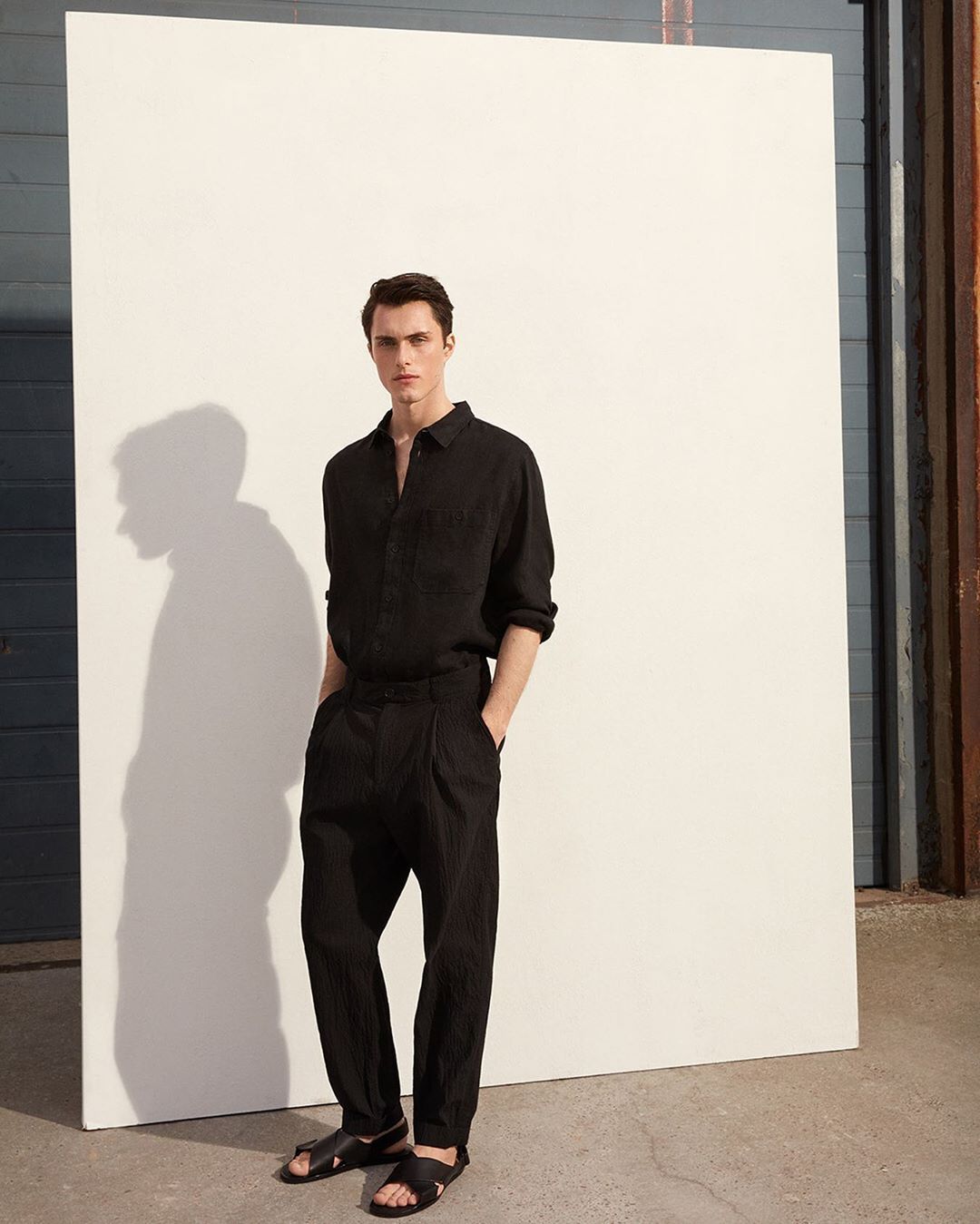

When it was founded in 2007, COS was supposed to be the champion of the H&M stable, already owning brands such as Weekday, Monki, & Other Stories and Arket. Its market position was intermediate: along the lines of Phoebe Philo's Céline and Isabel Marant, it offered elegant and minimal dresses, with a very Swedish aesthetic, equipped with architectural silhouettes and products with quality materials at affordable prices. Its positioning was a step higher than H&M (which was, both literally and figuratively, much more cheap) and one lower than the actual fashion brands, possessing a significantly lower price point. The idea of offering high basics to a more fashion savy audience worked well at the beginning: in the first ten years of life, COS's sales had reached one billion and made up 5% of the total revenue of the H&M group. But, as you can read in a long report by Business of Fashion, things were about to change.

While the group's business division director, Peter Ekberg, was talking about doubling the brand's turnover by 2022 in 2018, its performance has now fallen by 2%: from 1.06 billion dollars its revenues have fallen to 917 million. The Covid-19, Then, at the beginning of 2020, it dealt a huge blow to the H&M Group, which for years suffered from slow growth and declining profits culminating in the affair of the four billion dollars in unsold clothes lying in its warehouses in 2018, and that after the pandemic saw sales plummet by 50% in the second quarter – a loss resulting in the closure of several stores including seven stores in Italy. , the final chapter of a decline that is not only of COS or the group of which it is a part, but of the entire fast fashion system. After the resignation of three of the brand's top executives and an ever-declining performance, it seems difficult for COS to become the group's number two brand.

The three main reasons for the COS crisis can be summarized in the word "backwardness": commercial, aesthetic and cultural backwardness.

Retail problems

The root of all the problems of the brand is the way it reaches its customers: the whole world moves towards a digitized and de-localized retail, that is the opposite direction to that followed by COS that in recent years has instead relied on the spread in physical stores. Last year, the number of COS stores worldwide reached 291 units – a huge number of stores whose supply led to an overproduction of material that was constantly disposed of with massive discount campaigns, lowering the value of the brand. In Gartner's Digital IQ Index for 2019, which ranks the digital performance of brands, COS was among the last on the list in both the US and the UK.

This retail hypertrophy was also accompanied by a slow adaptation to the world of e-commerce. Also in 2019, digital was responsible for only 12% of all global sales. A decidedly low figure in a market increasingly dominated by the growth of the e-commerce sector. COS's e-commerce system, then, looks unsophisticated compared to that of other large retailers. One of the main features missing, for example, is the absence of integration of e-commerce inventories with those of the physical store – an elementary feature, present both on the Gucci website and on that of Ikea, to give an idea of its spread. Over the last few years, the big digital retailers have become increasingly important in the fashion landscape, such as the YOOX NET-A-PORTER Group or Farfetch, offering increasingly sophisticated and complex experiences and raising the expectation of customers towards the online shopping experience.

A missed opportunity

When COS arrived on the market, it found itself filling a void. Zara's re-branding had not yet taken place, just as there really was no commercial alternative to compromise between fast generalist fashion and luxury. The concept of elevated basic carried out by COS, its references to the world of architecture and art and its intermediate price point attracted the companies of all those fashion insiders who wanted to wear minimal and everyday garments that clearly distinguished themselves from the anonymity of fast fashion and without paying excessive sums.

But over time new competitors have entered the Western market, the main one of which is Uniqlo, and being able to position themselves in an intermediate price range as COS has tried to do has become increasingly difficult. The consumer who has to buy a white t-shirt, for example, is more likely to buy it in a fast fashion chain spending less or looking for a luxury brand spending more than looking directly for the intermediate option proposed by COS. In short, COS is in the inconvenient position of a brand that is too expensive for the generalist masses but too current for the luxury clientele – its strength has become a weakness. A missed opportunity when you consider how brands had all the potential to become the benchmark of a New Luxury, the first clothing brand rich in style but fully democratic - an achievement that, in truth, for any brand would be difficult to achieve but, if it were achieved, could have an epochal weight.

Although the aesthetics of the brand have remained very consistent over the years, it has not been accompanied by a system of values properly transmitted through social media. COS's aesthetic has remained unchanged and essentially an end in itself - closed in the monotonous stereotype of essential Swedish design. The result was a fading brand identity. Not to mention that the main appeal of fast fashion is its rapid imitation of luxury trends, reproposing them at democratic prices. It is an unsustainable model but that works and satisfies the fickleness of the clientele – a model that COS has not followed over the years, stopping to be in step with the times and falling into repetitiveness, especially in an era when a defined and structured aesthetic has become increasingly important for the customer who wants to identify with the values and narrative of a brand.

Diversity and Instagram

In a fashion industry increasingly characterised by ethical considerations and topics such as inclusiveness and cultural diversity, COS's strategy to address the issue has seemed antiquated. The brand's employees, interviewed by Business of Fashion anonymously, spoke of a decidedly uninclusive corporate culture in which "casting of more diverse talent remains a battle." The lack of diversity would also be found in the design of the clothes, guilty according to some of not being thought for every body type. This is also the H&M Group's poor reputation for exploiting workers in developing countries – a bad reputation that began with the collapse of Savar's Rana Plaza, the worst fatal accident in the textile factory's history, which produced clothes for the group.

These shortcomings are attributable, according to the Business of Fashion survey, to the monoculturality of its management, unsuitable to face an increasingly multicultural market. The same investigation reports that over the years there have been numerous complaints from employees about a closed, nepotistic corporate culture marked by ambiguous incidents of bullying and abuse of power promptly minimized or silenced by the brand.

What is COS doing to change?

At the end of last January, the role of Managing Director of the brand passed to Lea Rytz Goldman who succeeded Marie Honda, who remained in her position for the last eight years. Goldman's former role was the management of Arket, one of the youngest brands in the H&M Group portfolio as well as one of the most promising.

Goldman has already begun to make healthy changes for the company, such as an in-house workshop to redefine brand identity, enhancing e-commerce and establishing an open forum where employees can expose the problems they face in the workplace.

It is still too early to know whether the change of leadership will result in a real improvement in the performance of the brand – but COS is not a moribund company: its performance, although unsatisfactory compared to the past, remains strong; the brand has a its own identity and commercial potential as well as the financial and infrastructure support of one of the world's largest industrial conglomerates. First, Goldman intends to create a new corporate culture based on trust and geared towards positive change:

«As a new leader, when you want to create an open environment and an inclusive culture, that takes time. And I, together with the leadership, have to create trust for people to be able to speak up».