The great story of the white t-shirt From embarrassing underwear to cornerstone of the world's best wardrobes

The history of fashion, and even more the history of streetwear, is essentially composed of garments and materials that, born to perform humble practical functions, have become over time and through the increasingly iconic culture. What is opulent for a century, is ridiculous for the next century, just as what humble, offensive or embarrassing for the past can become normal for the future. The best example of this process, which sees the bass continually rise upwards and, in contrast, what at the top gradually disappear, is the white t-shirt, the most ubiquitous and universal garment of all, whose story begins in the moralistic world of post-Victorian underwear, then winding through wars and cinema screens until it landed on the musical stages of counterculture and finally, on the fashion catwalks. In short, the history of the white t-shirt follows the history of the same modern society: for every moment-milestone of the last century, a new meaning has been layered on it, making it the indispensable classic that is today.

Origins: from underwear to military uniform

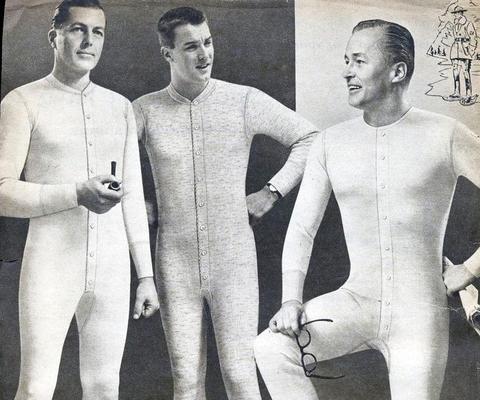

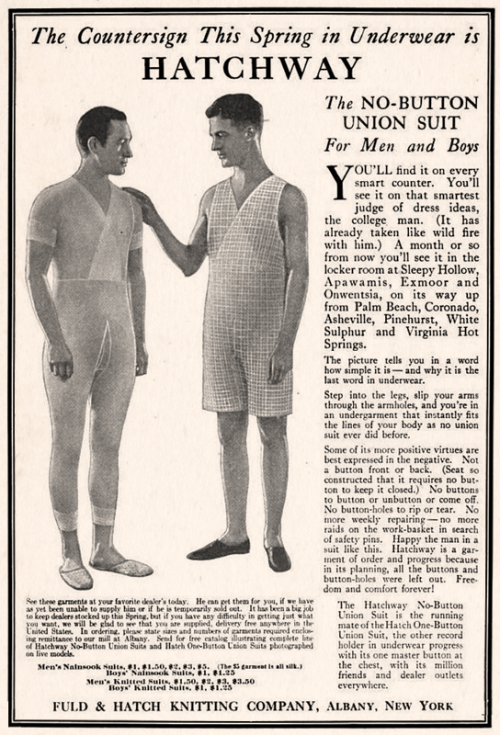

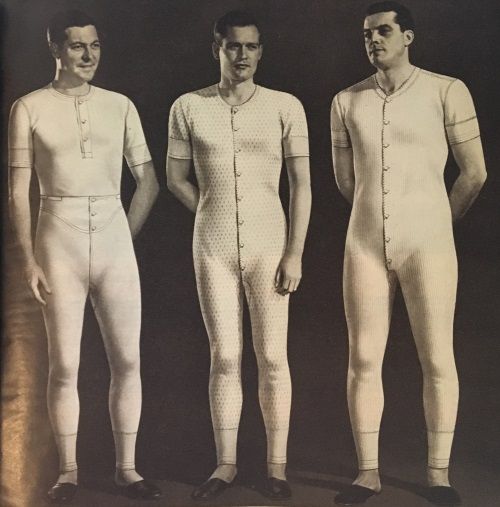

In 1869 in New York was patented the union suit, a sort of overall suit that covered the entire body and that, being an economic and warm garment, was soon associated with the working class and consequently treated with a certain contempt. The next evolution was the bachelor suit of the Cooper Underwear Company, born in 1909, which implemented the division between top and bottom. The top later became known as hanley – a name taken from the Hanley Regatta, being the garment a favorite of athletes during their workouts.

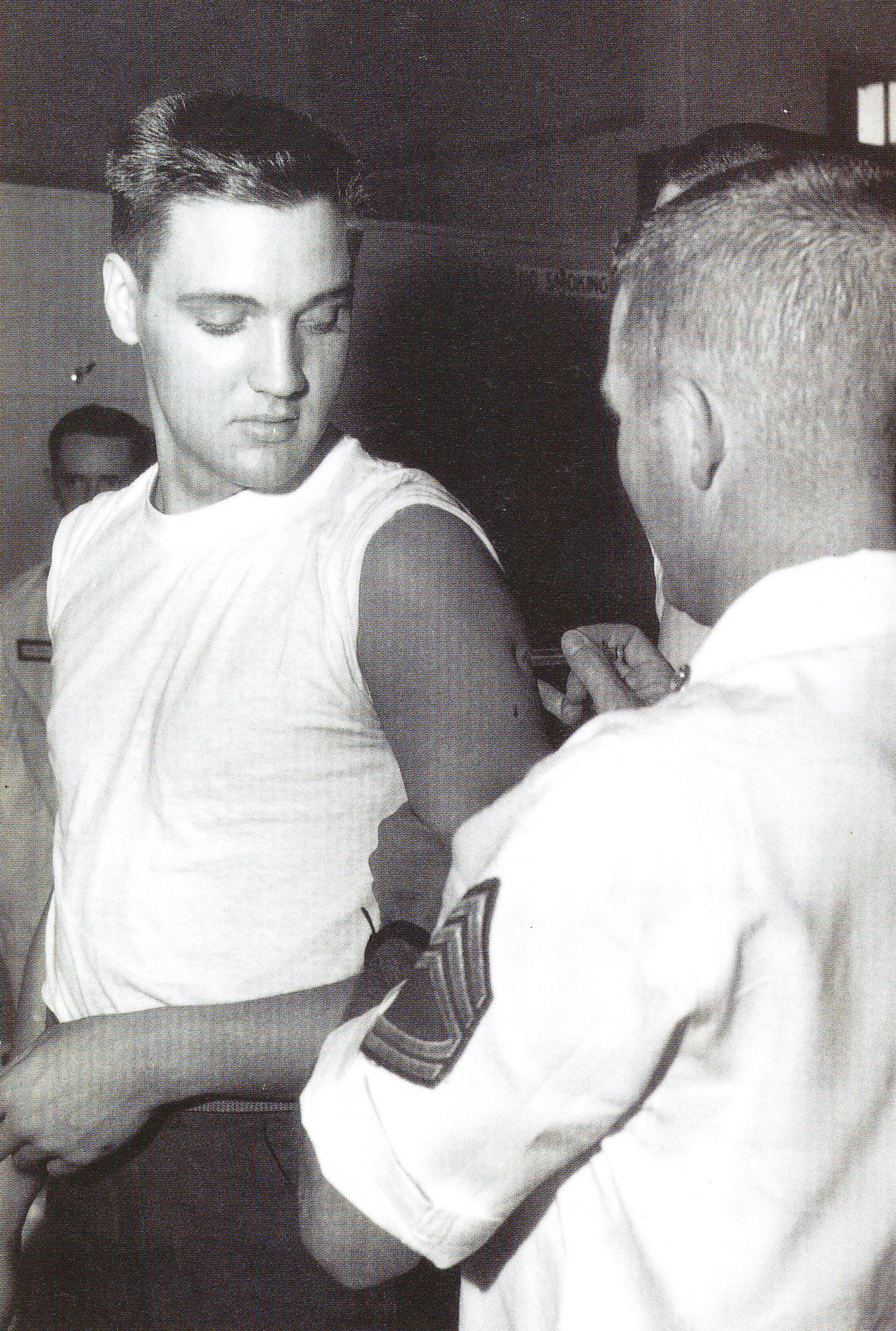

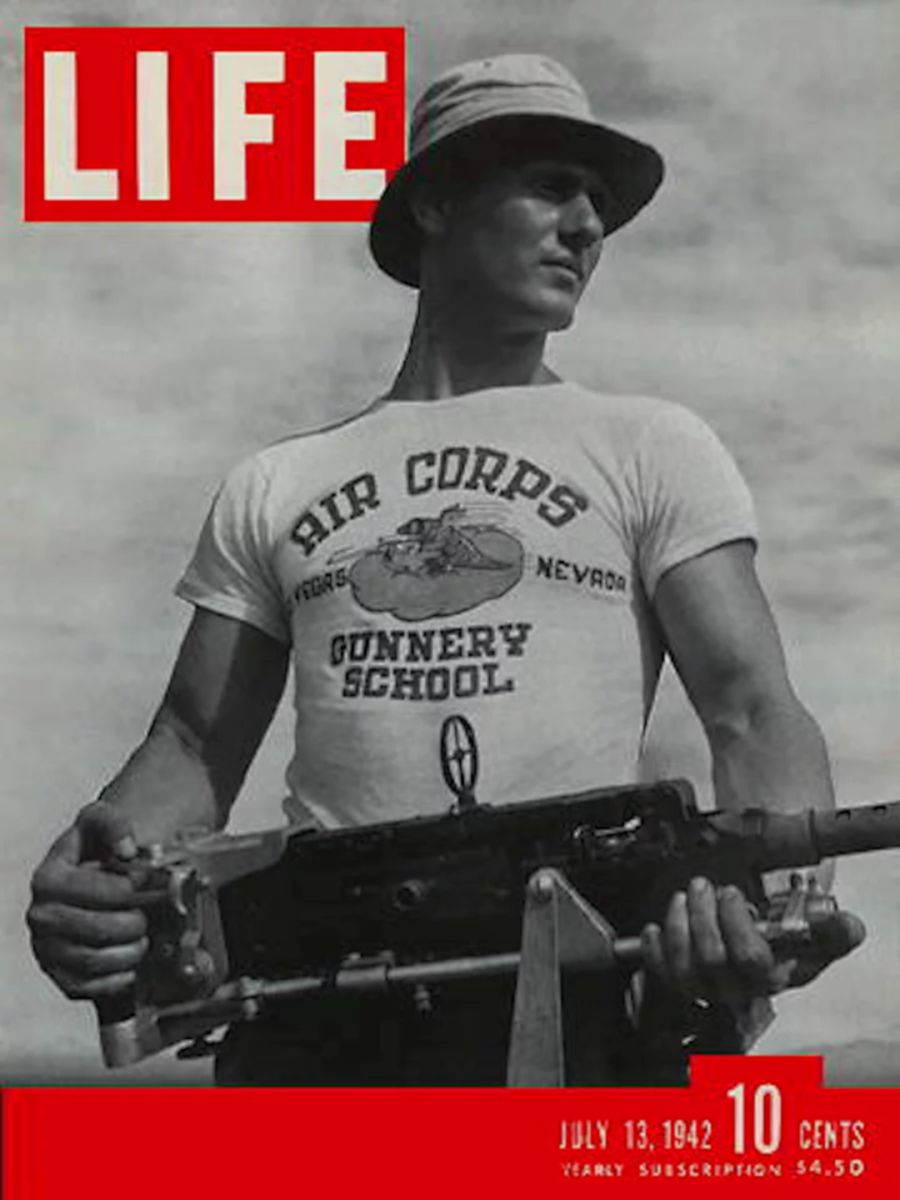

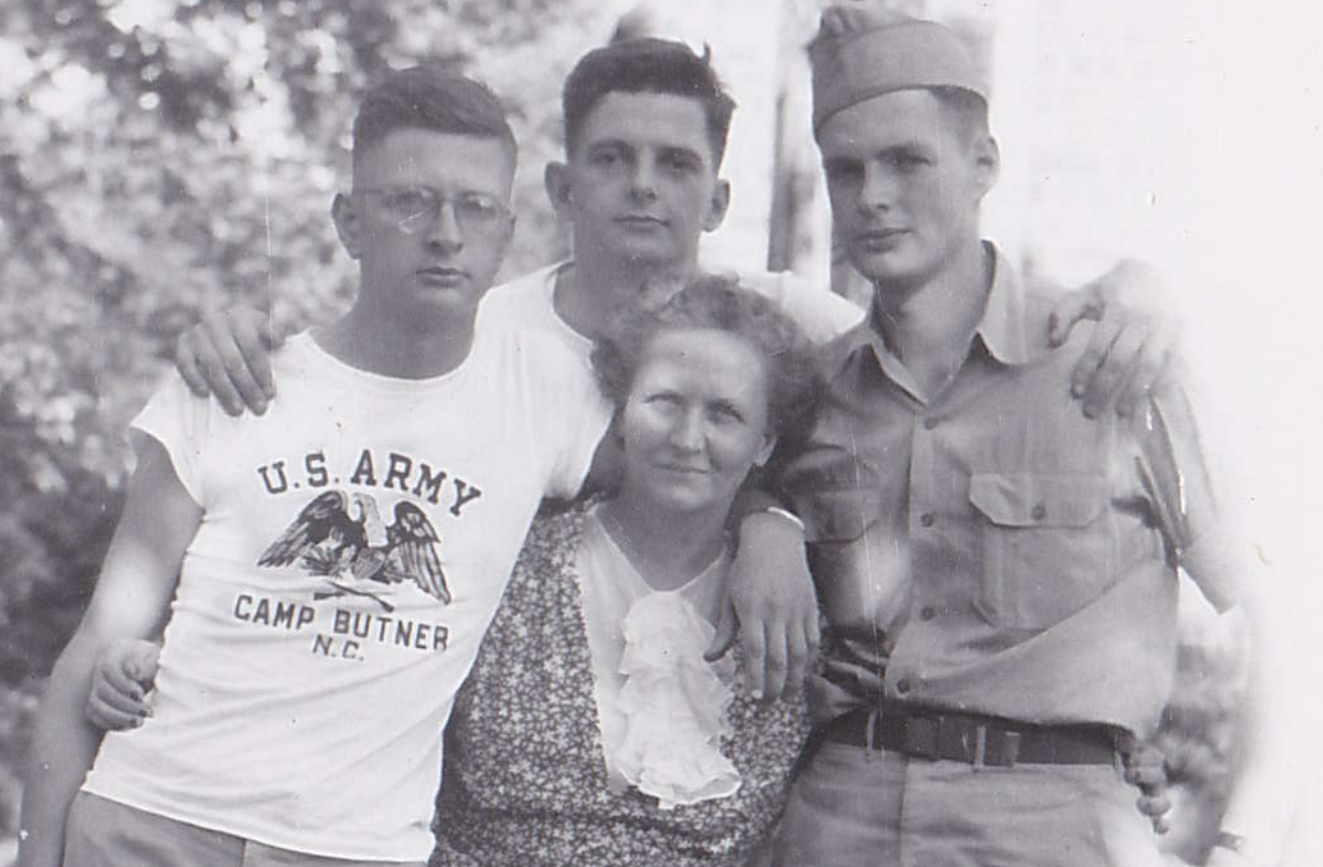

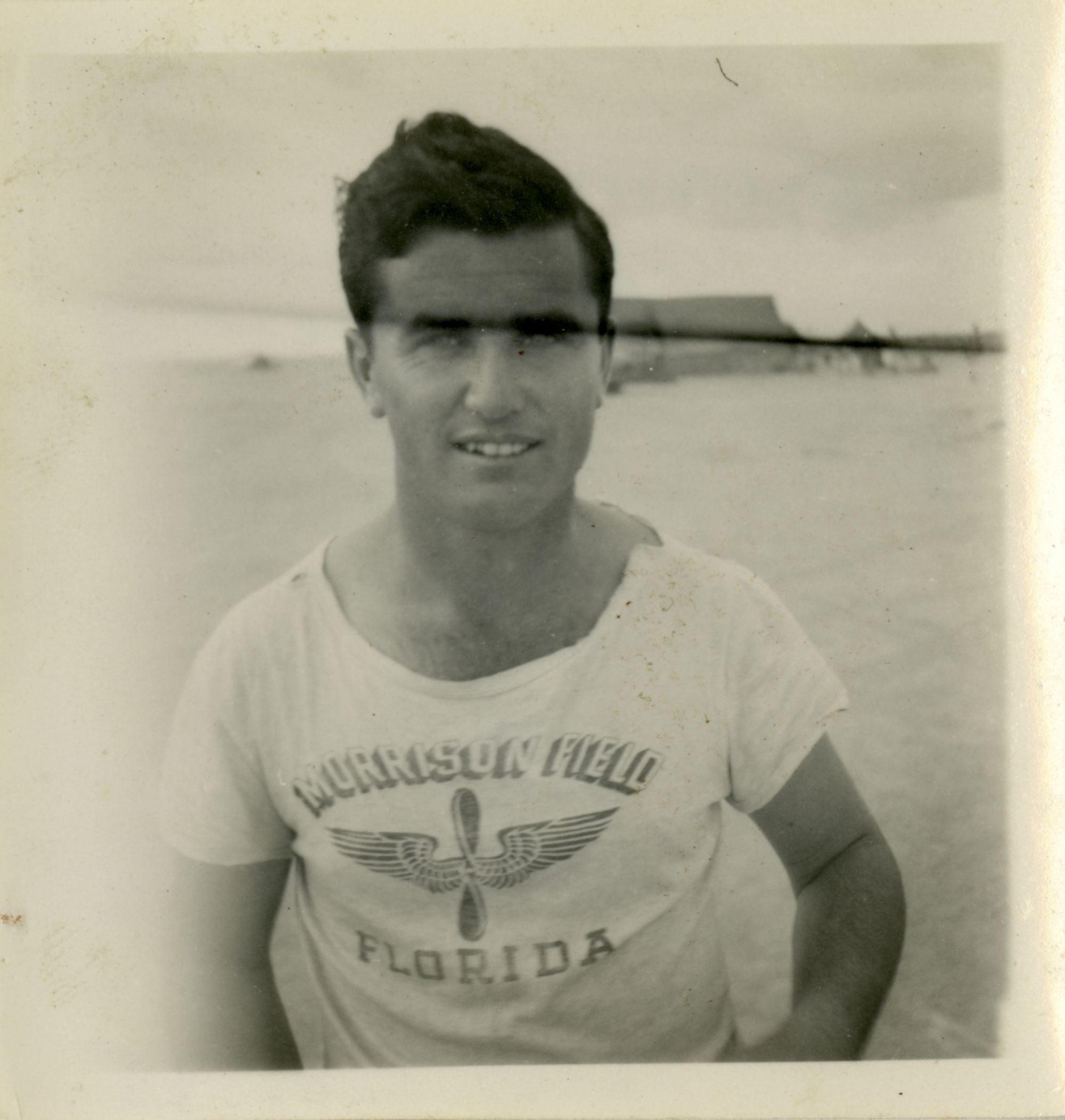

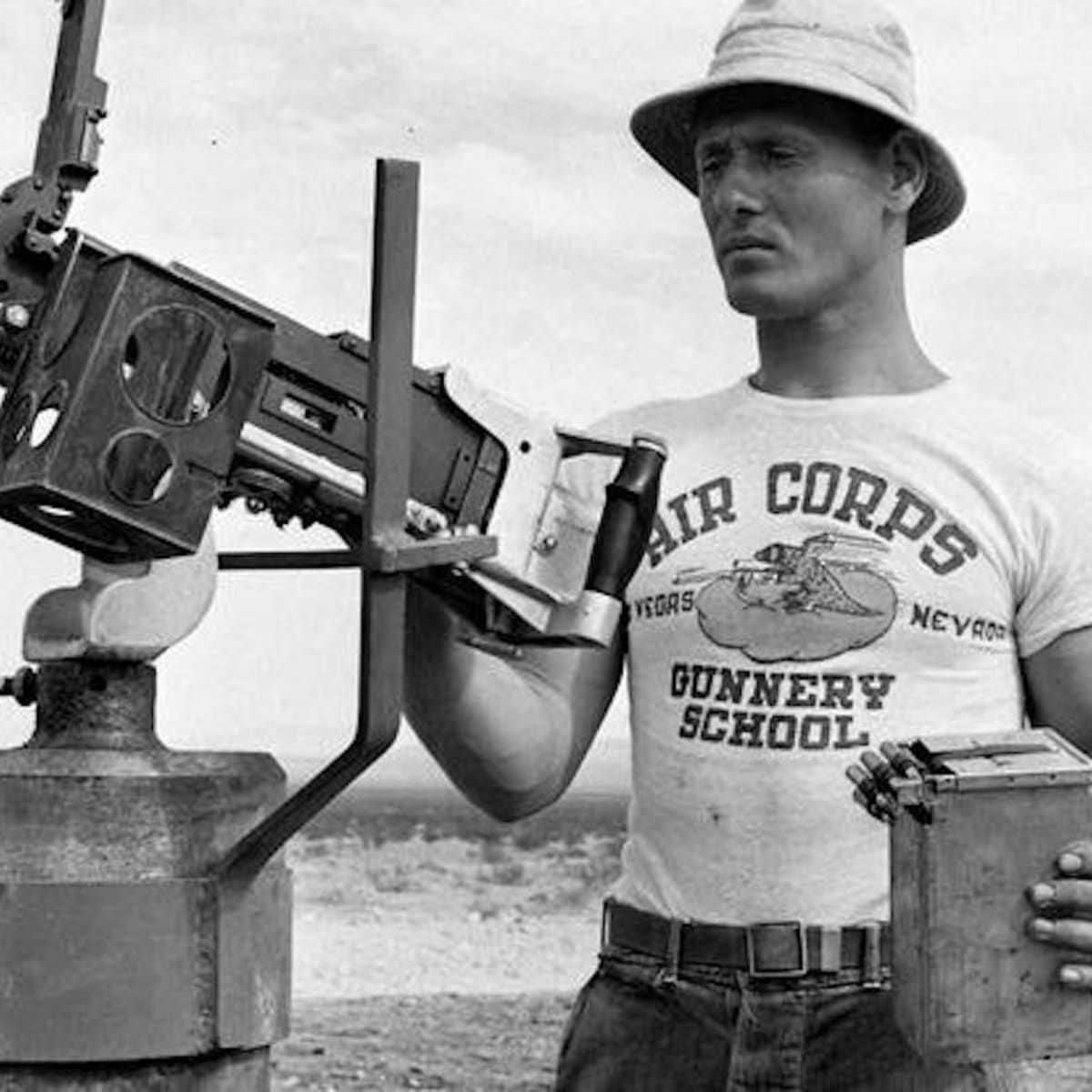

The henley went from sportswear to military wardrobe when the U.S. Navy made its soldiers' regular uniform in 1913. A few years later, Hanes was awarded a contract to supply short-sleeved shirts to the U.S. Army – an upgrade designed for military personnel stationed in tropical geographies. Meanwhile, World War II was on the way. While Hanes devoted himself to other supplies for the Army, the official manufacturer of white T-shirts for the U.S. Navy became Velva-Sheen.

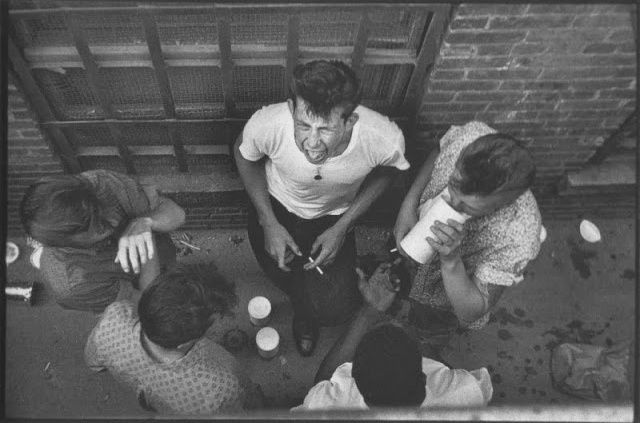

Newspapers and war bulletins began to spread photos around the world of American soldiers stationed around the world smoking Lucky Strike wearing white T-shirts after fighting - a symbolic image of american heroism and the genuineness of the working class. Those same soldiers returned home with a climate of post-war optimism that also saw dress codes relax and t-shirts to come out of the military world to spread like loungewear or workwear.

The rebellion

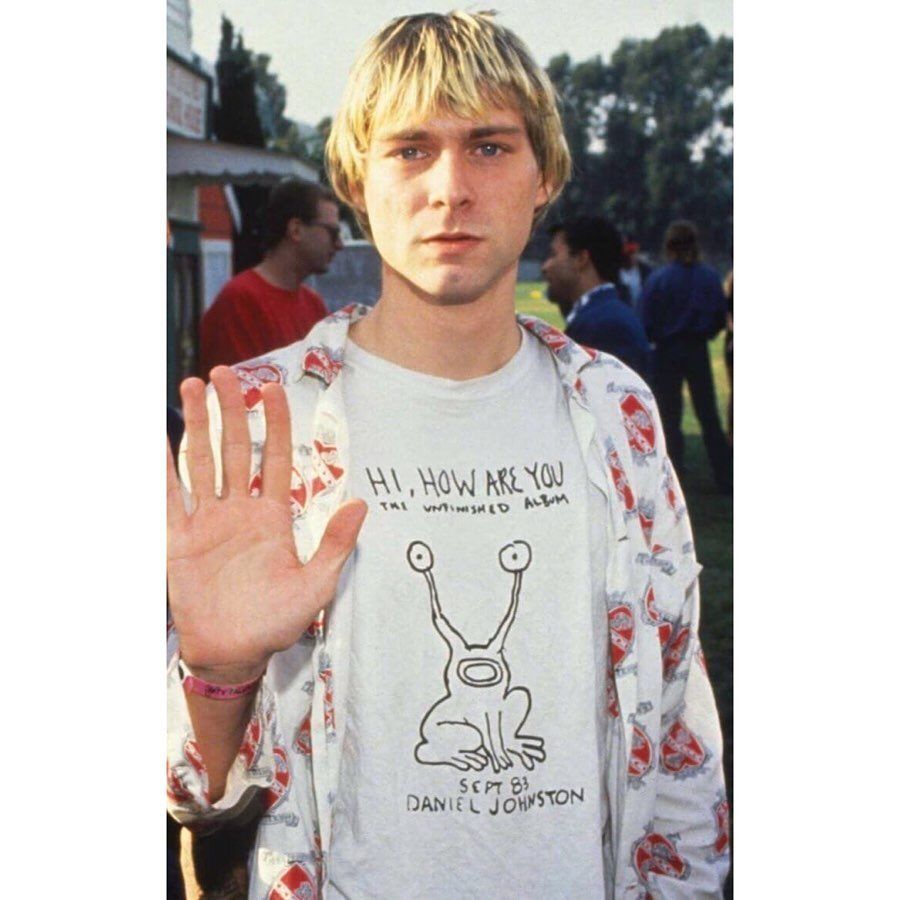

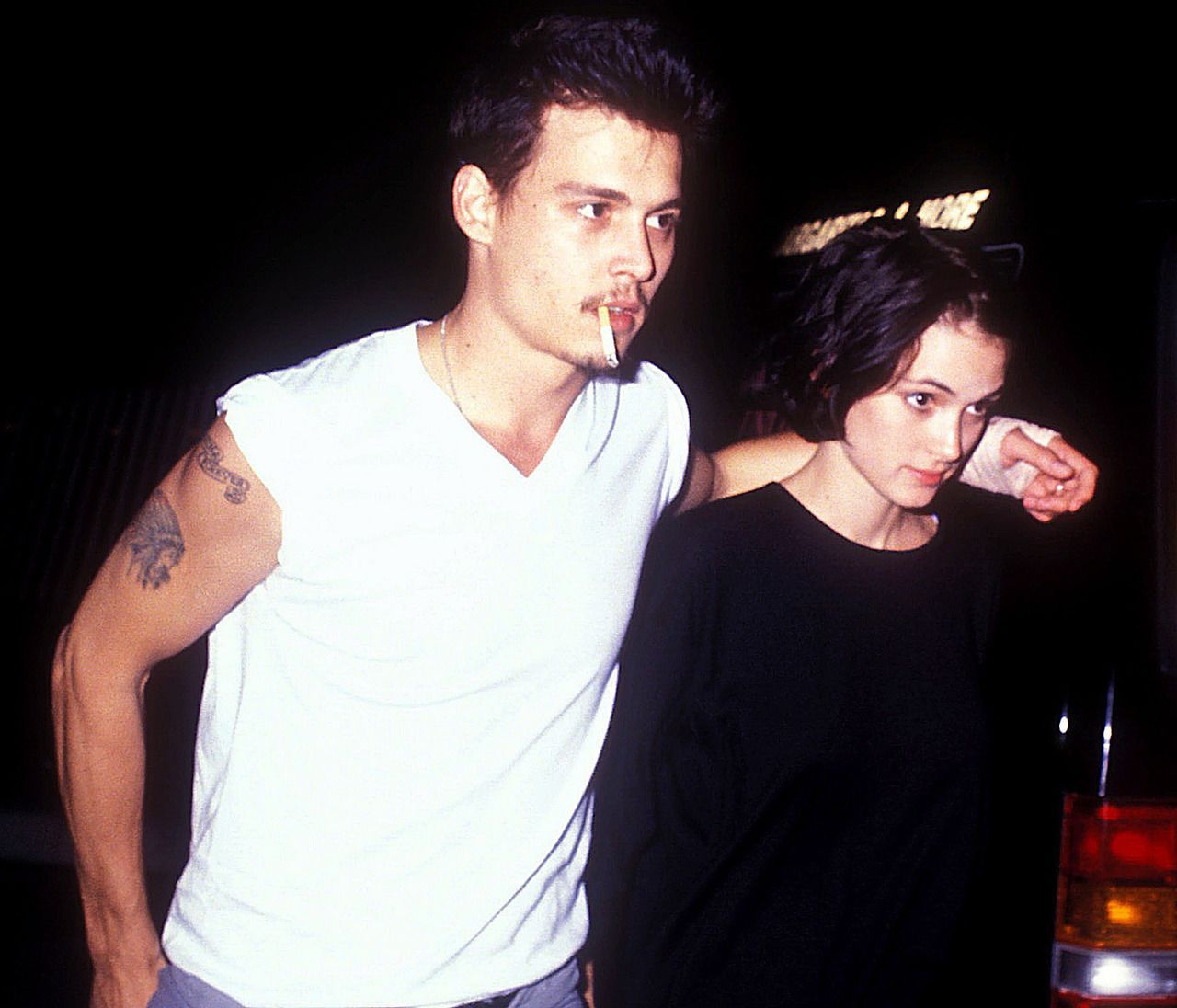

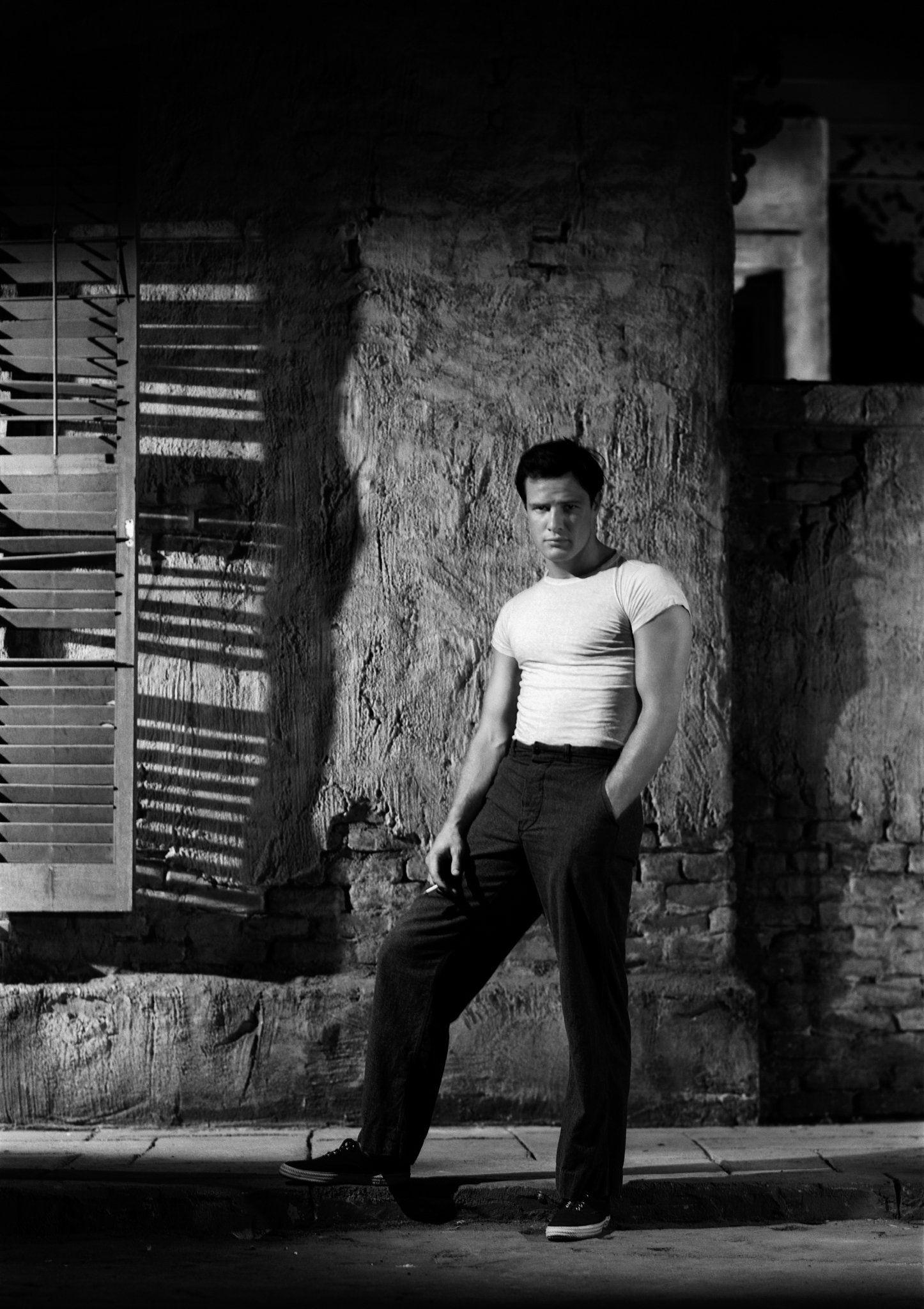

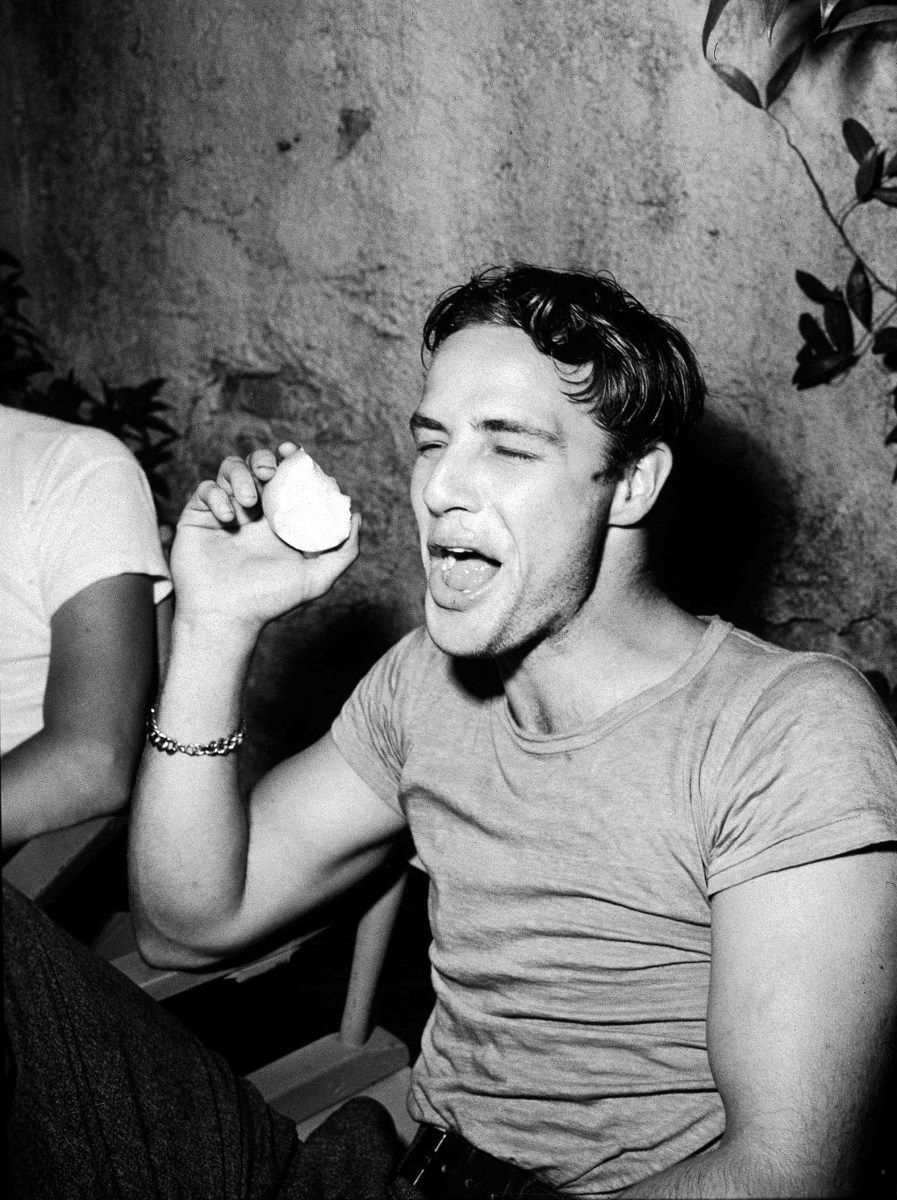

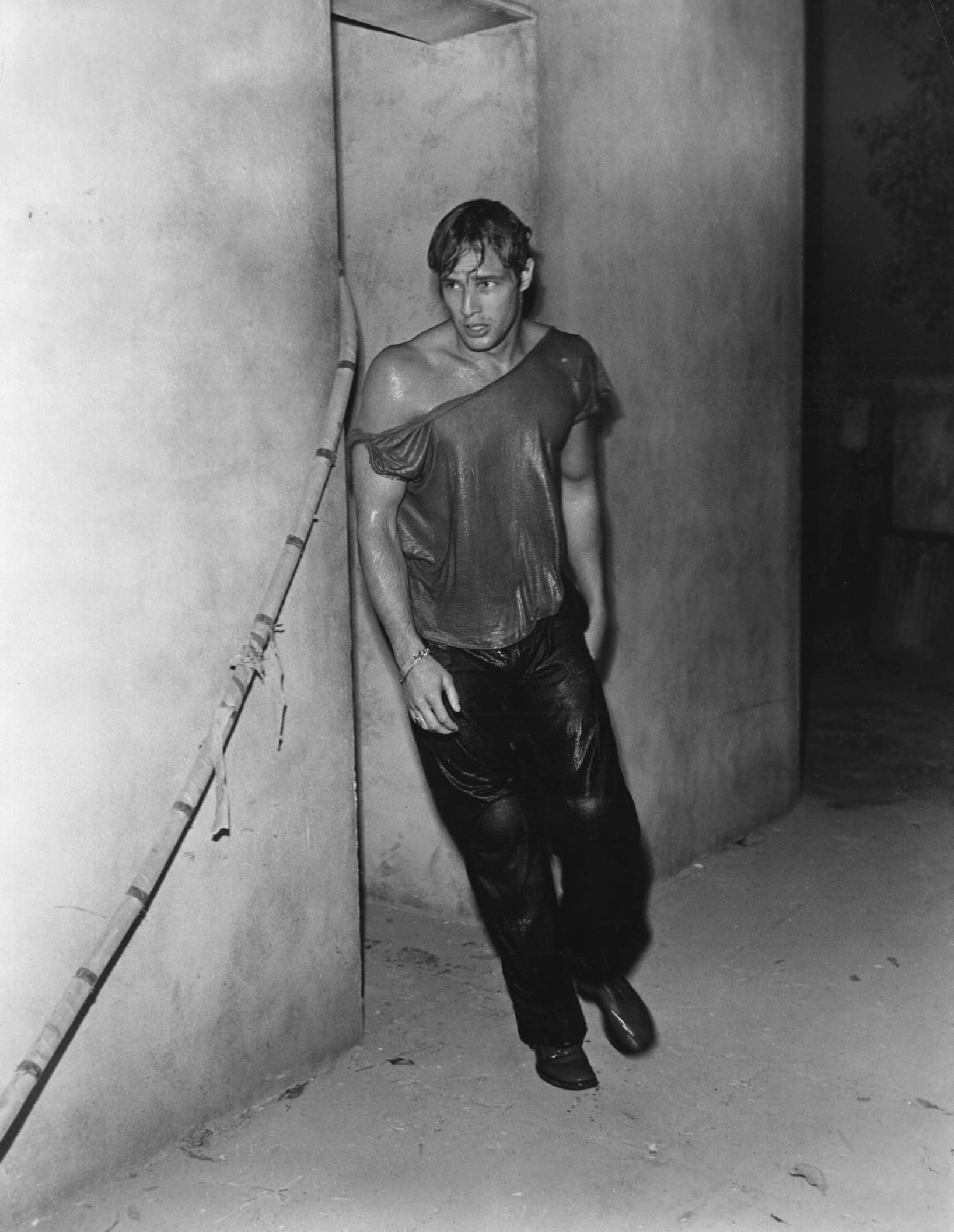

Two years after the end of the war, in 1947, Tennesee Williams debuted in a Broadway theater with one of her greatest masterpieces of playwright: A Streetcar named Desire. In the title role there was a young Marlon Brando and his character, Stanley Kowalski, was a sensual, alcoholic and violent man – to express the traits of his personality on screen and convey a sense of nudity, the costume designer Lucinda Ballard dressed Brando of two of the most plebeian garments of the time: a white t-shirt and a pair of tight Levi's 501. The success of the play, which spoke of taboo topics for the era such as sex and alcoholism, was sensational, winning a Pulitzer and becoming a film four years later, again starring Marlon Brando. From then on, a man wearing a T-shirt on screen was the same as a woman in her underwear and bra – a sexually charged outfit, outrageous, but still acceptable at the cinema because it wasn't too revealing. In the formal fashion world of the 1950s, the t-shirt had become a sexy garment, the badge of rebellion as opposed to the shirts and jackets of the bourgeoisie.

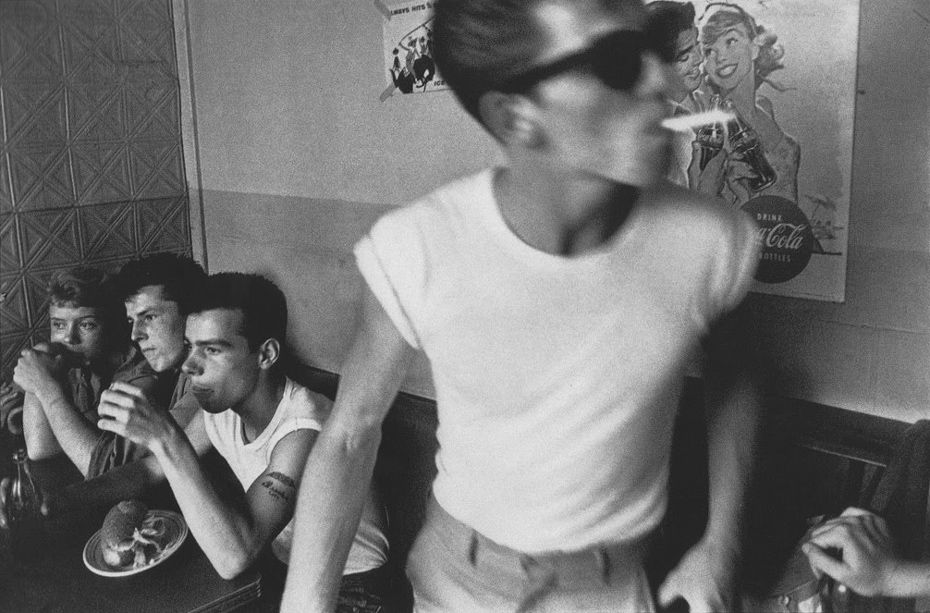

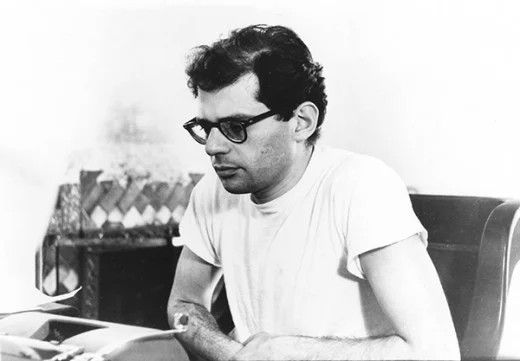

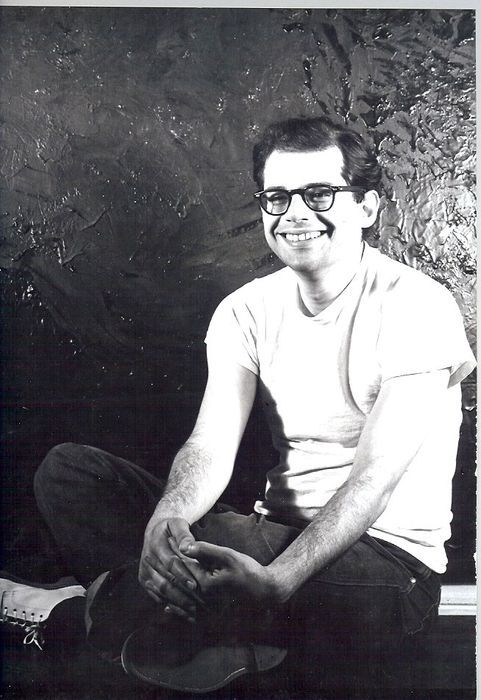

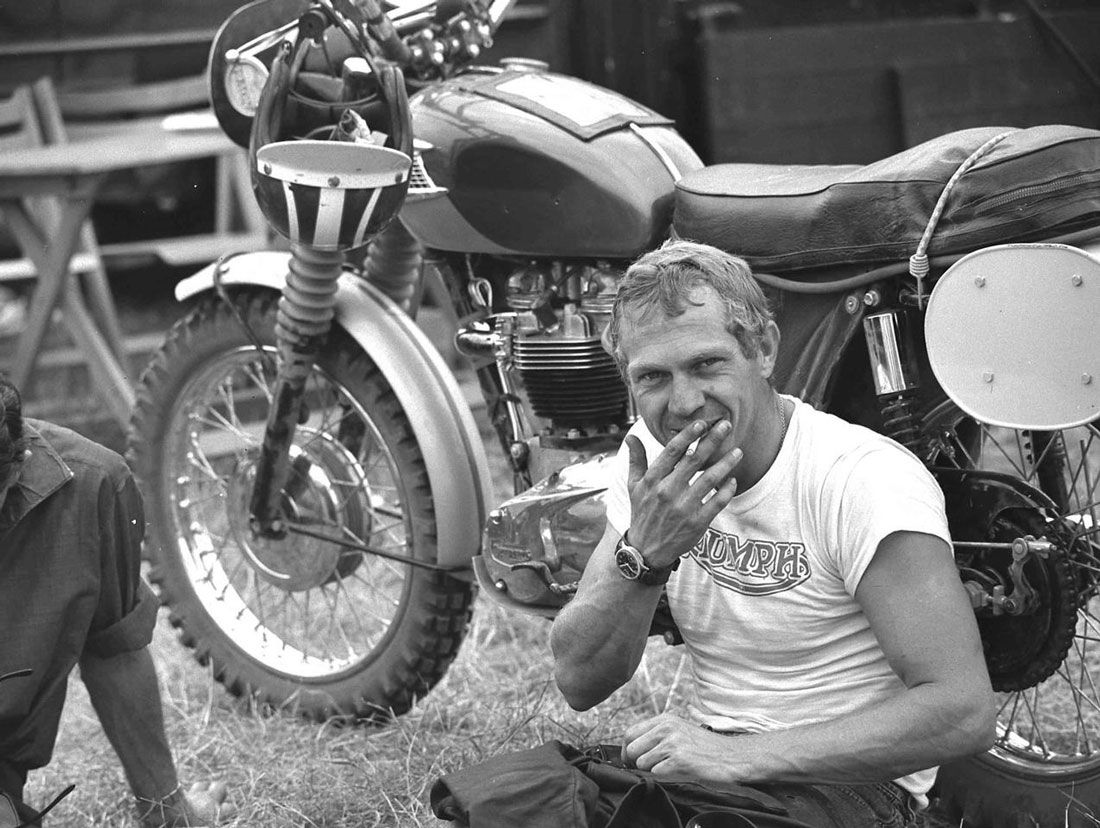

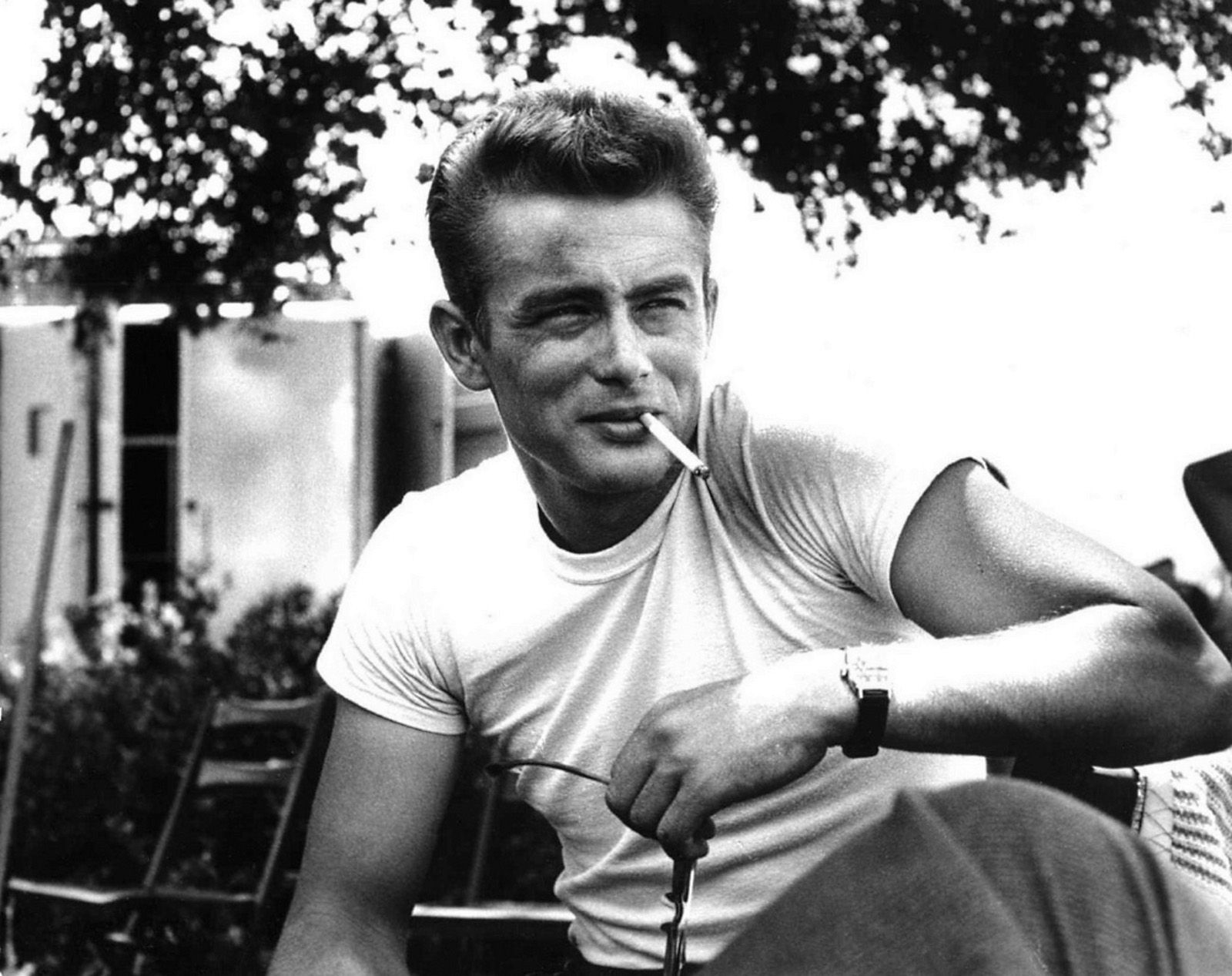

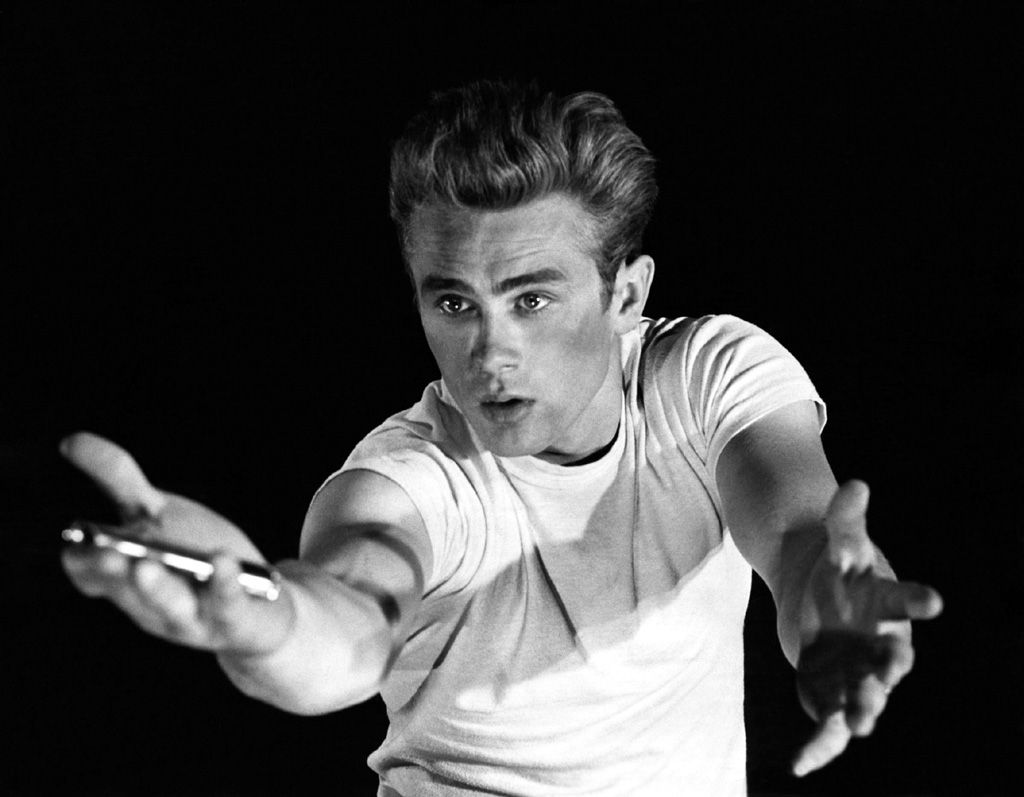

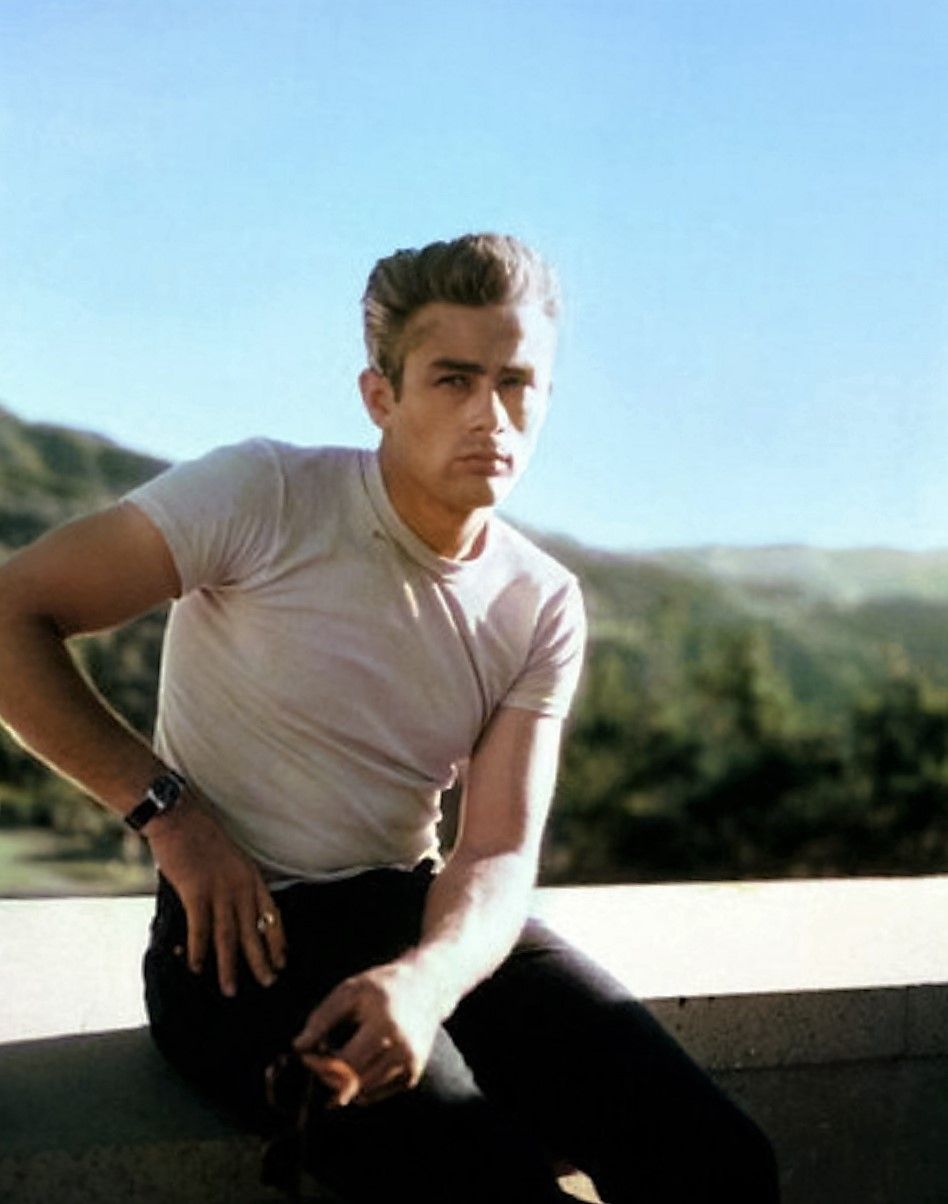

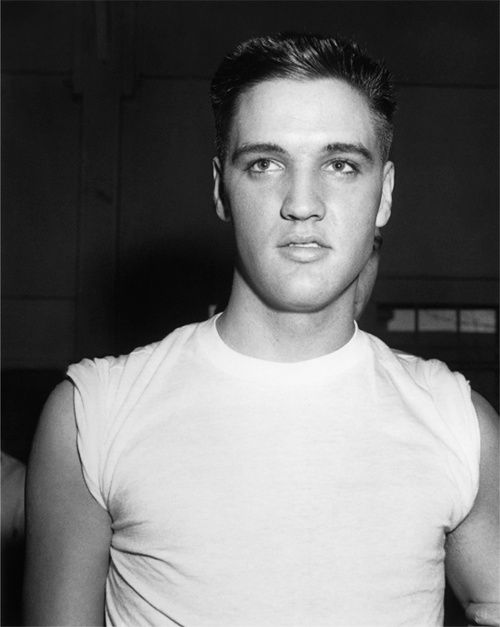

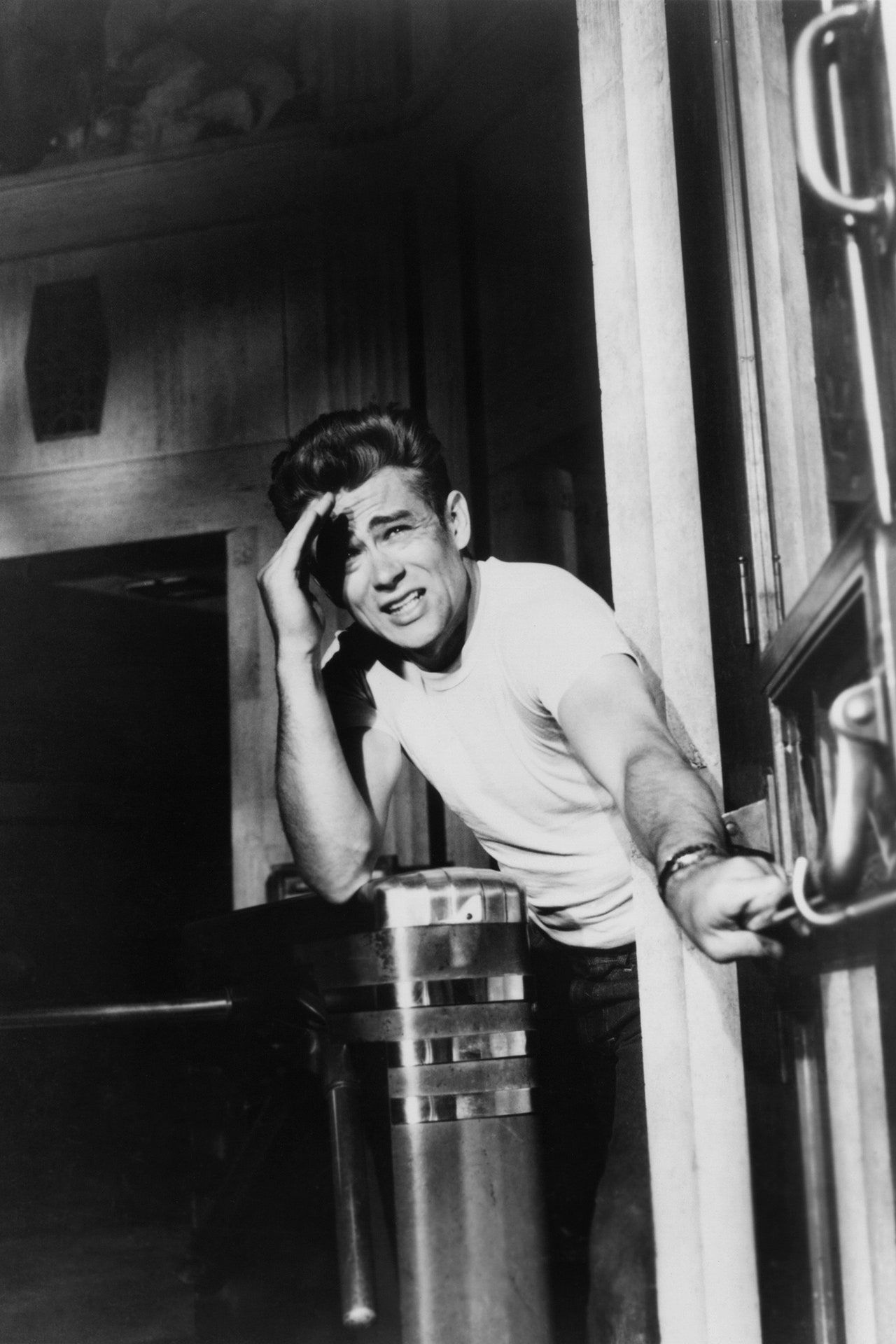

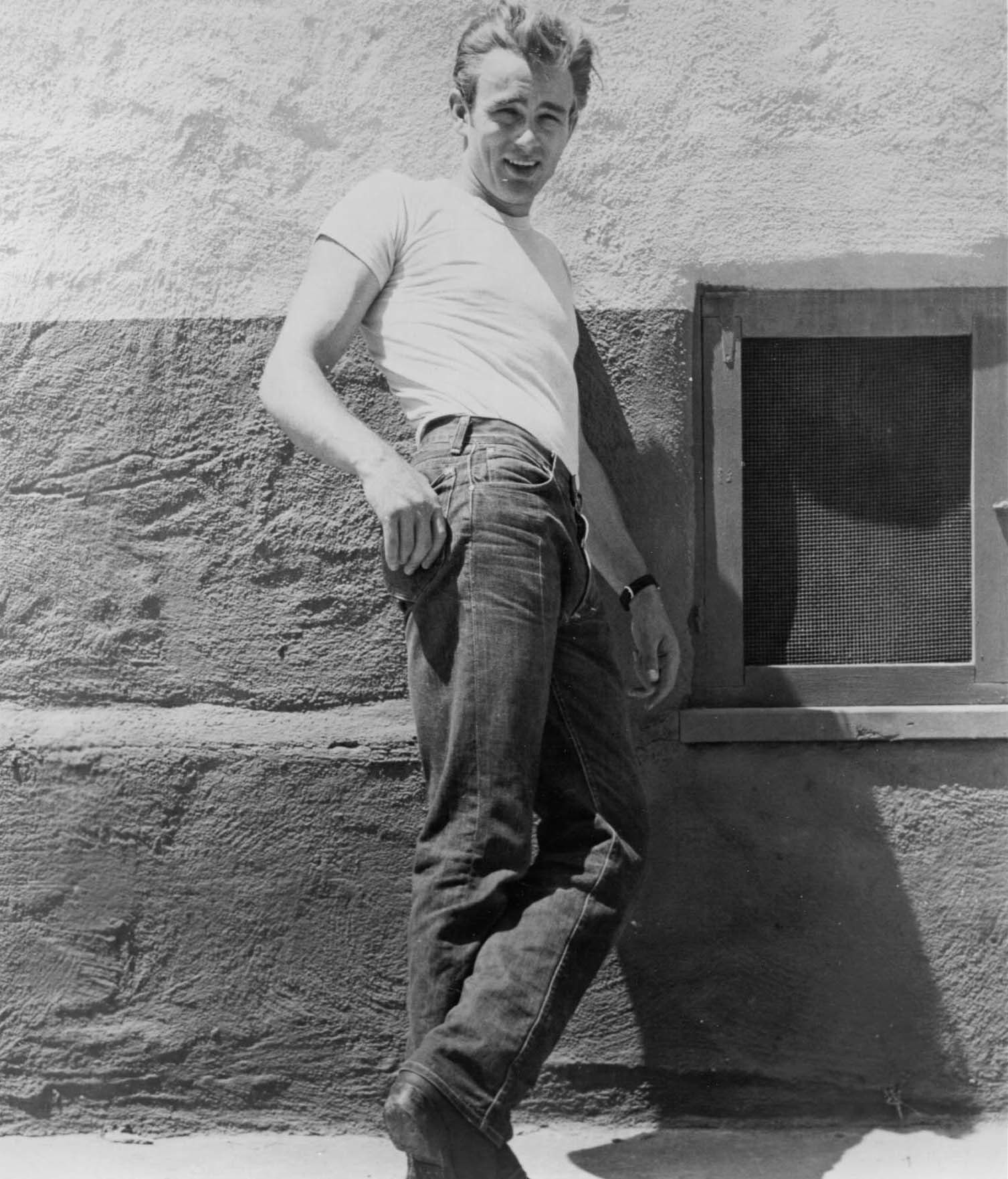

Fast-forward four years later. In America comes one of the most fundamental films of youth culture ever, Rebel without Cause – the first responsible for the creation of the myth of James Dean. For the duration of the film, Dean wears nothing but jeans and a white T-shirt. The film is important because it is one of the very first films to seriously represent the problem of juvenile delinquency. The t-shirt goes from being a simple sexy garment to becoming the symbol of disobedience - an economic garment, irreverent towards the rigidity of formalwear of the previous generation. The following year in 1956, the first rock star in history, Elvis Presley, took to the stage in a white T-shirt and began selling t-shirts linked to his name and image – the music merchandise was born. The charm of Brando, Dean and Elvis made the t-shirt a choice of style rather than a practical necessity and the garment was adopted by the culture of bikers, beatnik intellectuals and all those countercultures that went against the formal mainstream of the time.

The symbol of the counterculture

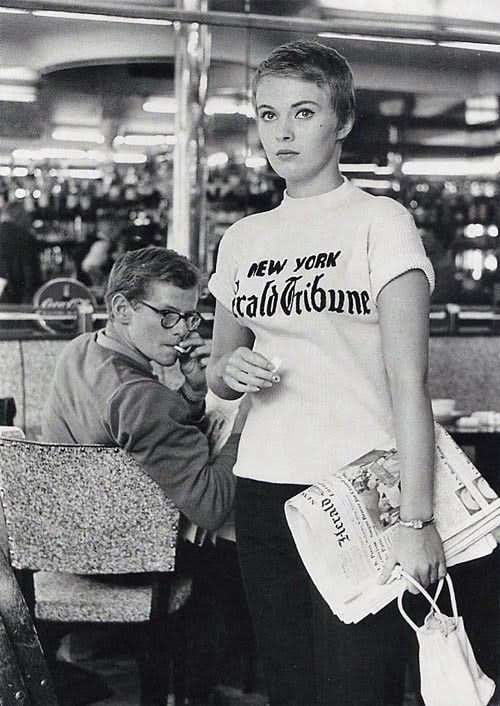

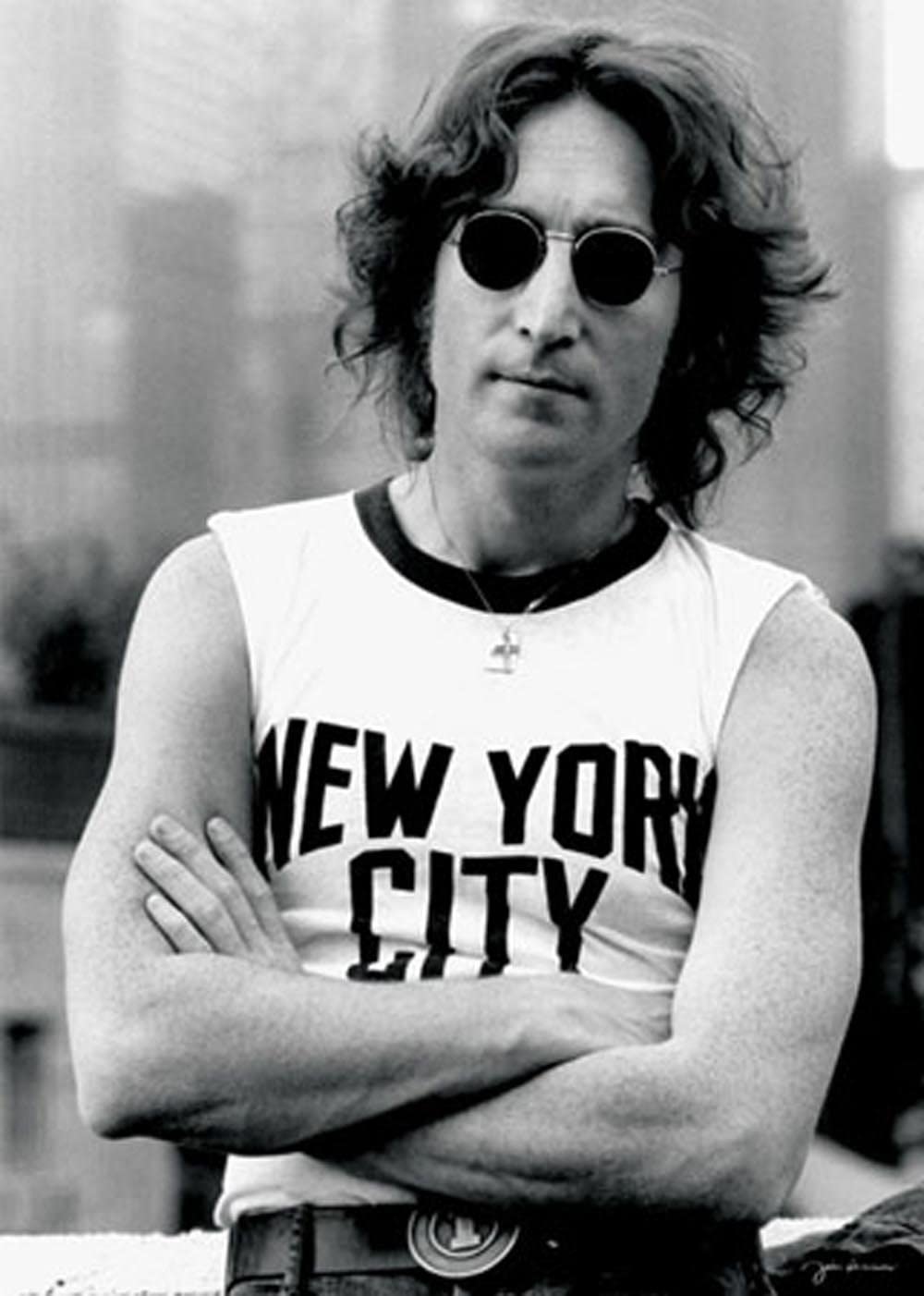

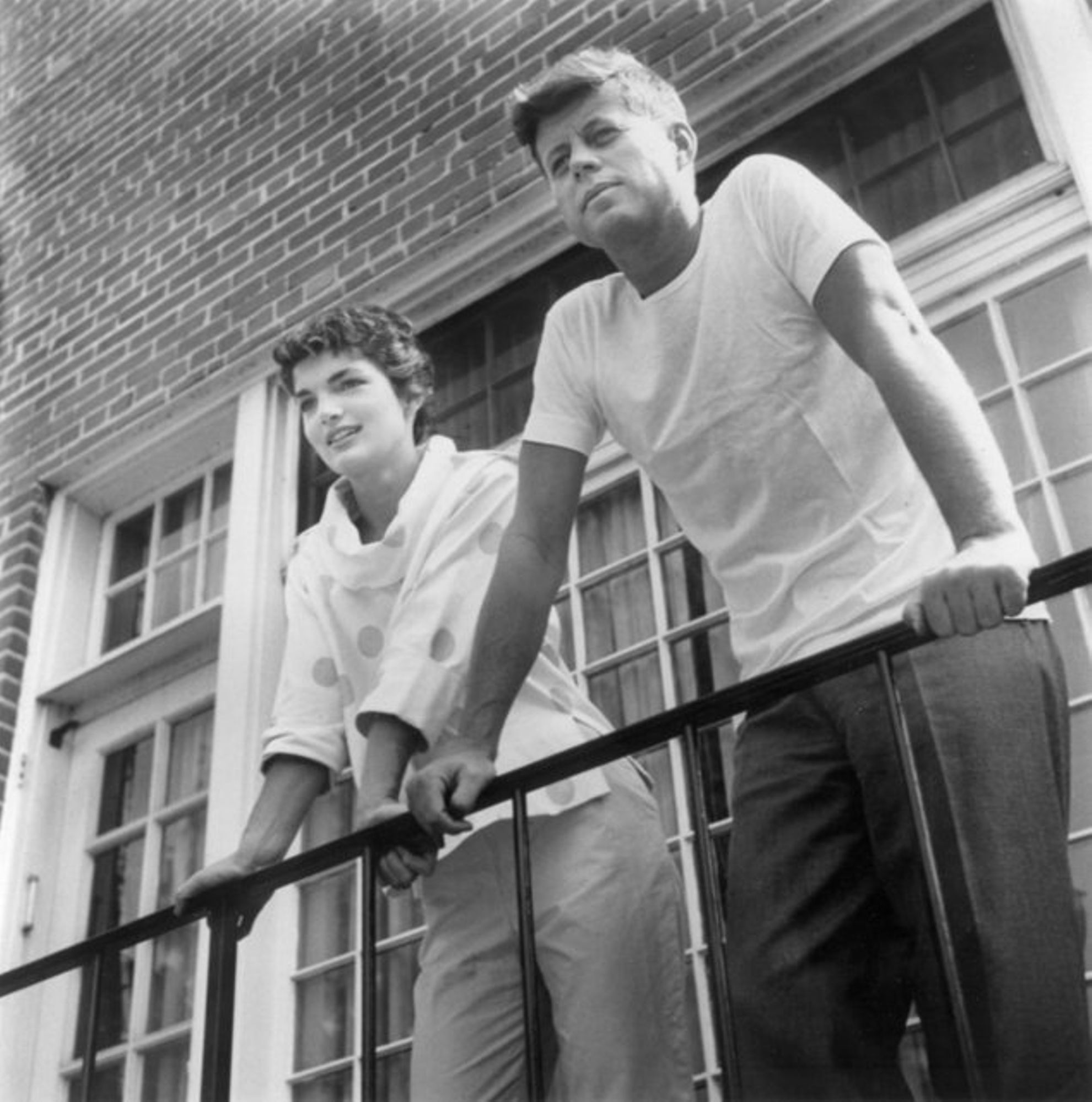

During the 1960s, the rise of the t-shirt continued. Jean Seberg in Godard's Breathless introduced her to the repertoire of French style. Even John F. Kennedy and his wife Jacqueline Bouvier were photographed, before he was elected President of the United States, wearing one. During the 1960s, however, the fate of the t-shirt was entrusted to music. Its status as a blank canvas on which any kind of message could be written and exhibited was permanently consolidated.

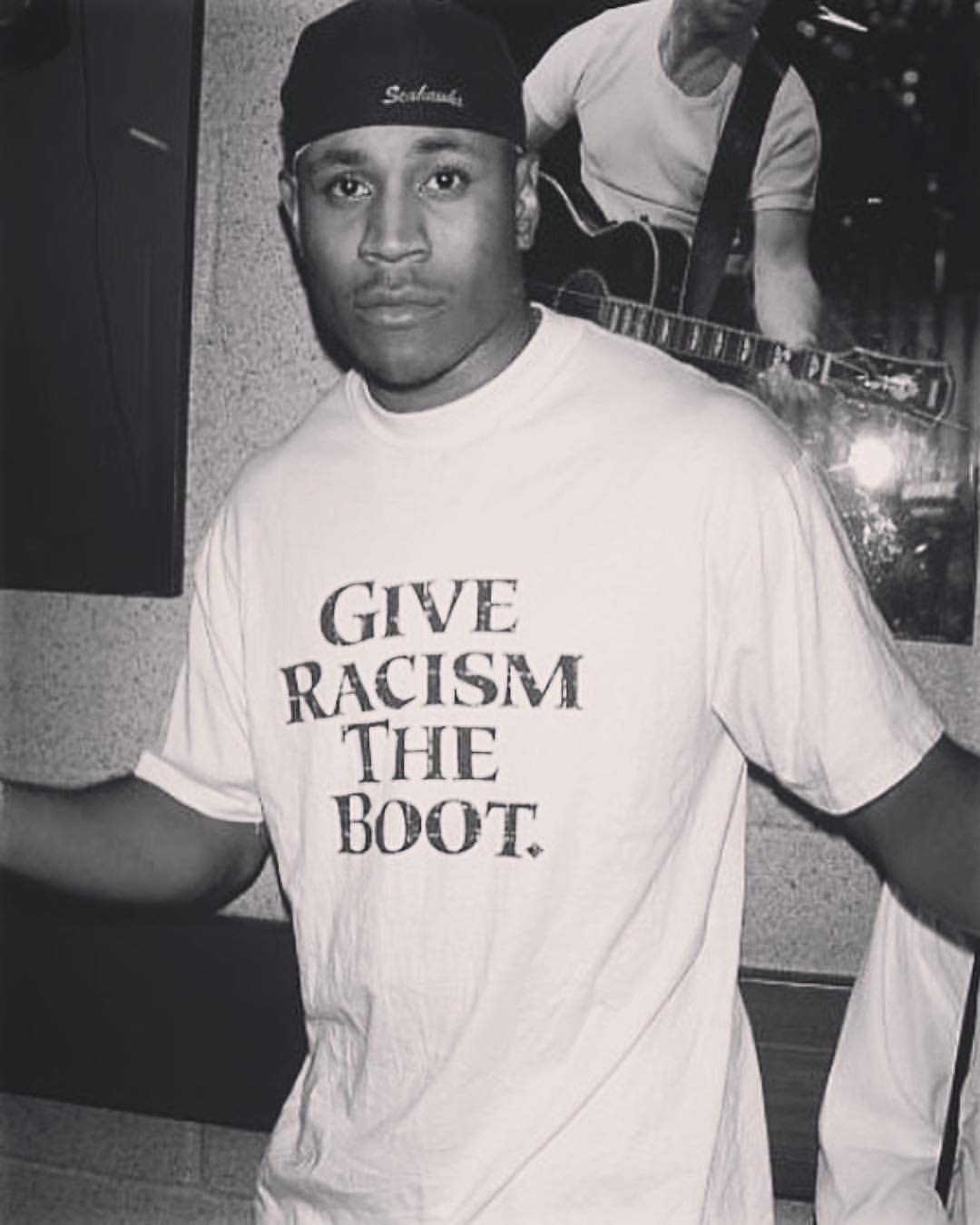

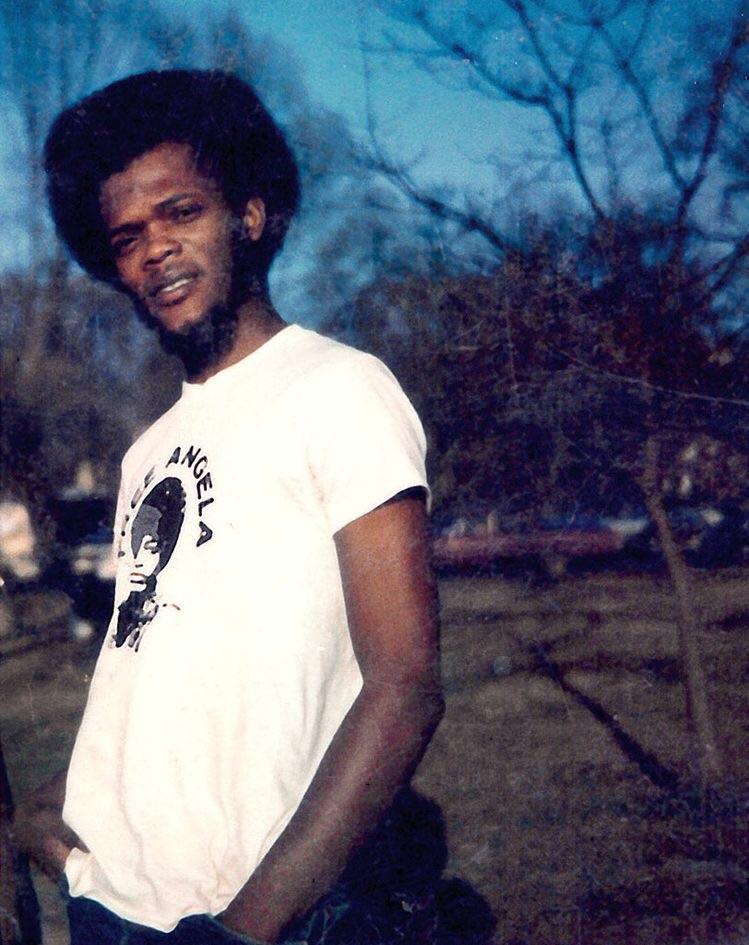

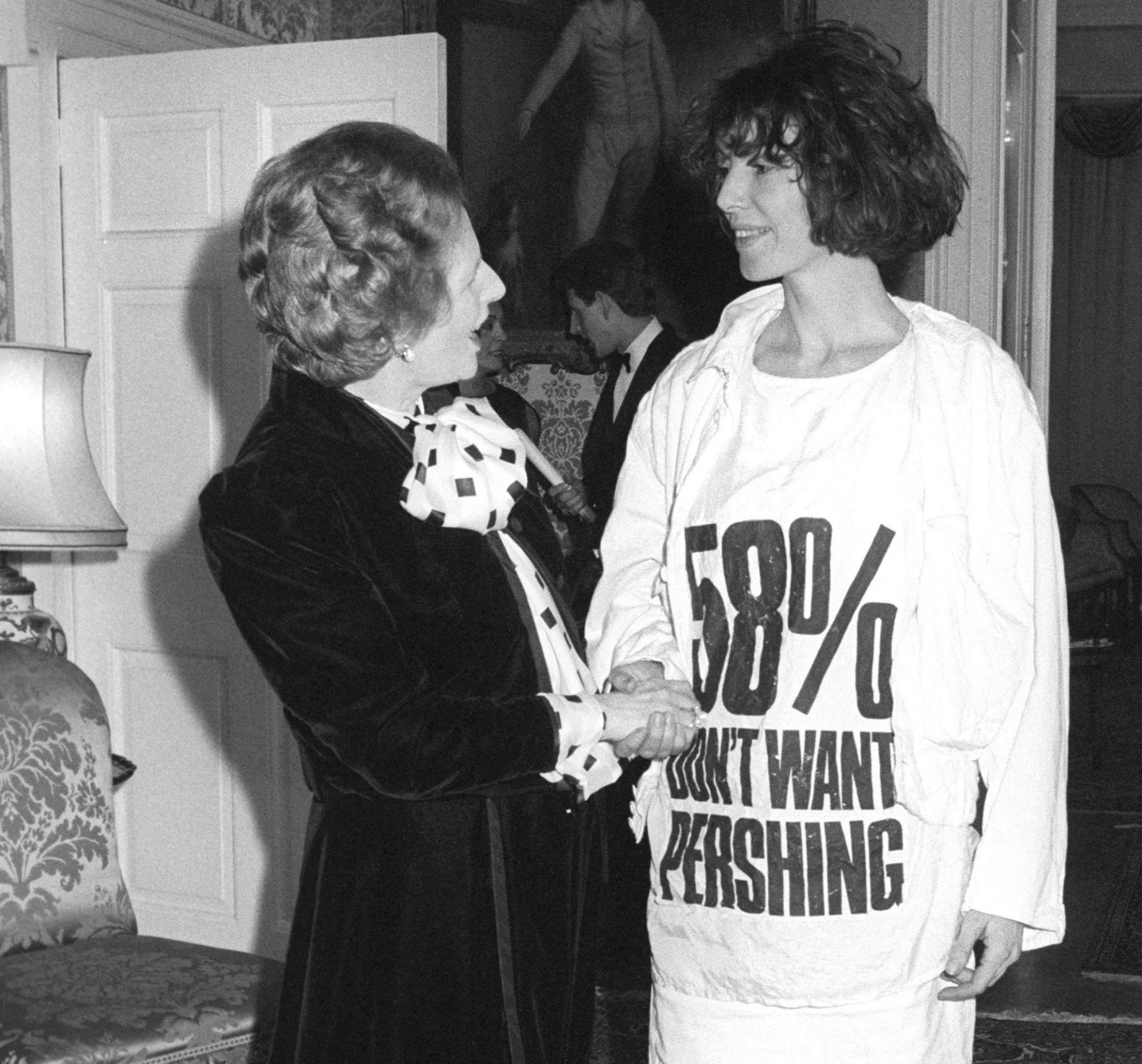

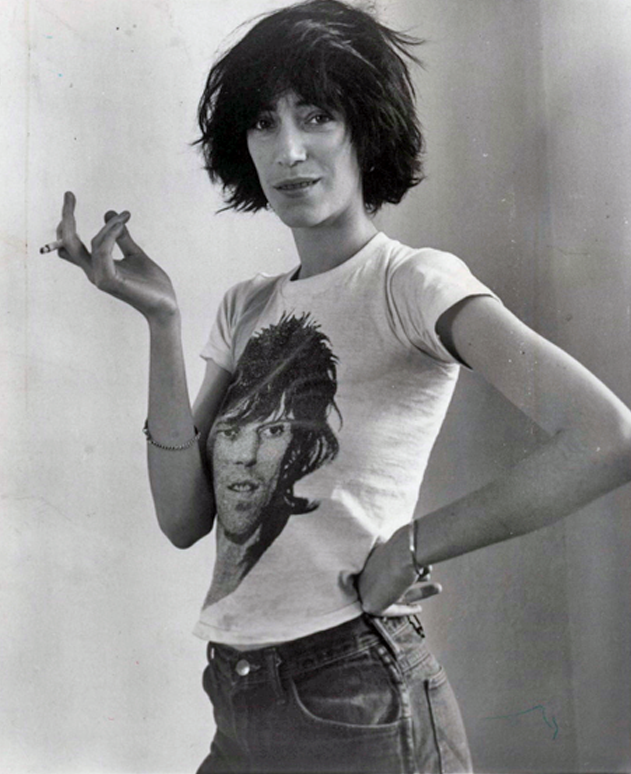

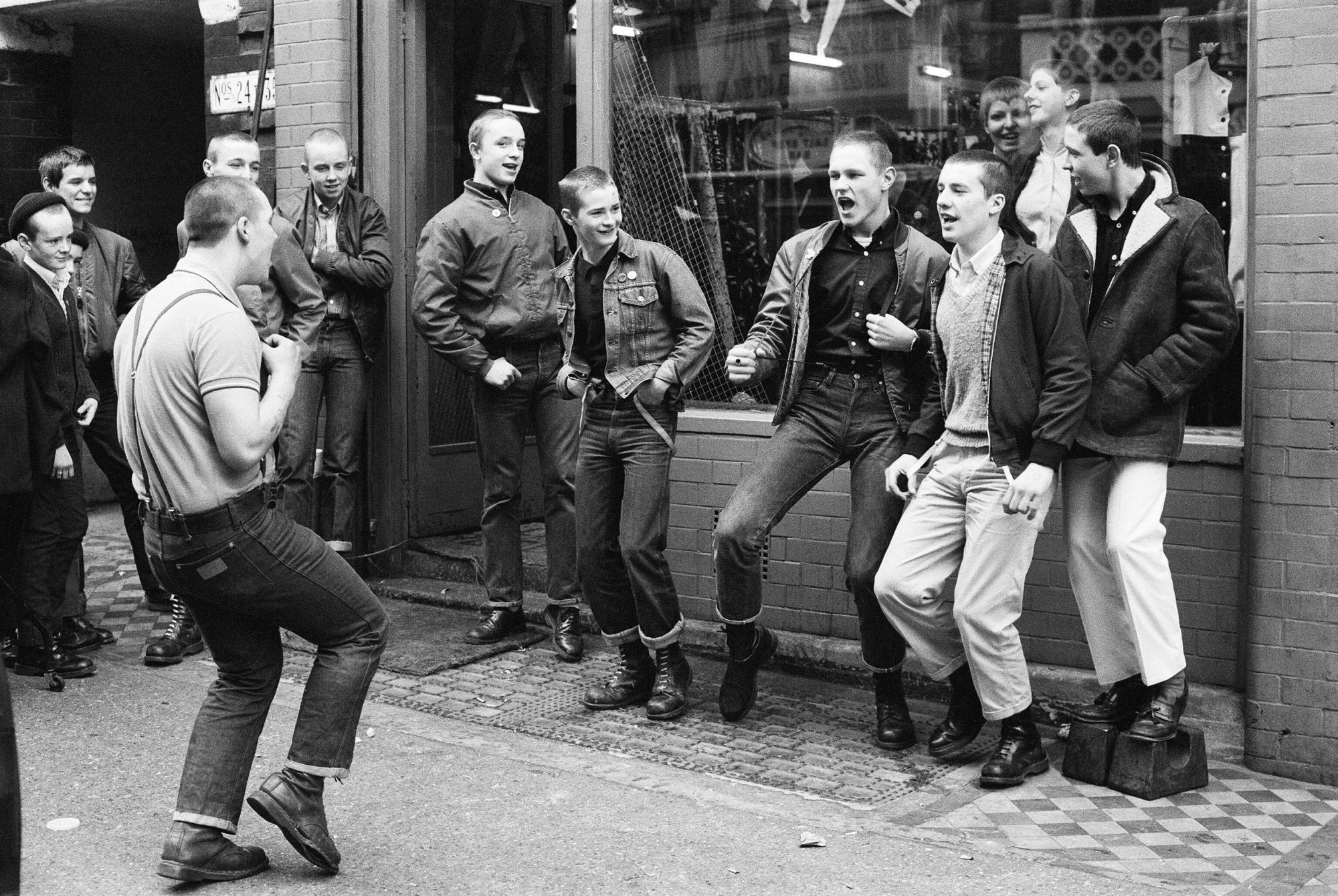

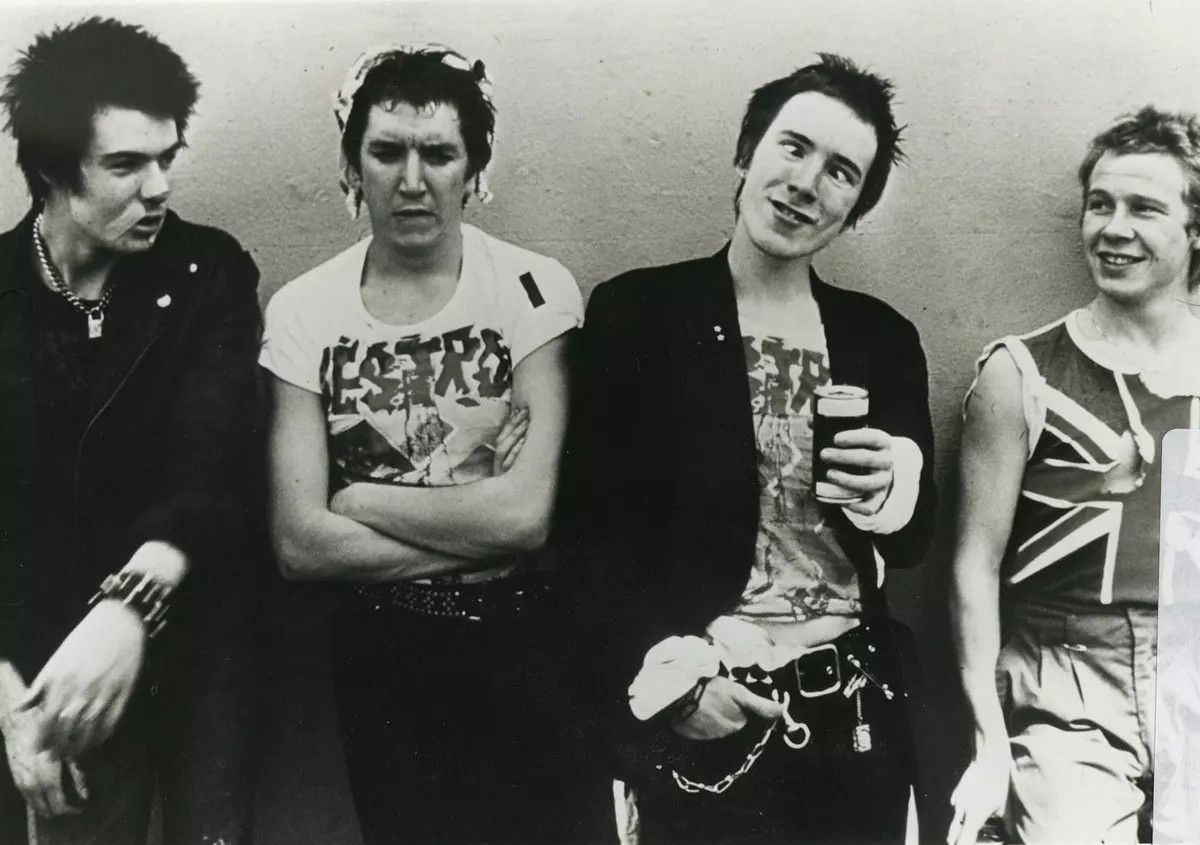

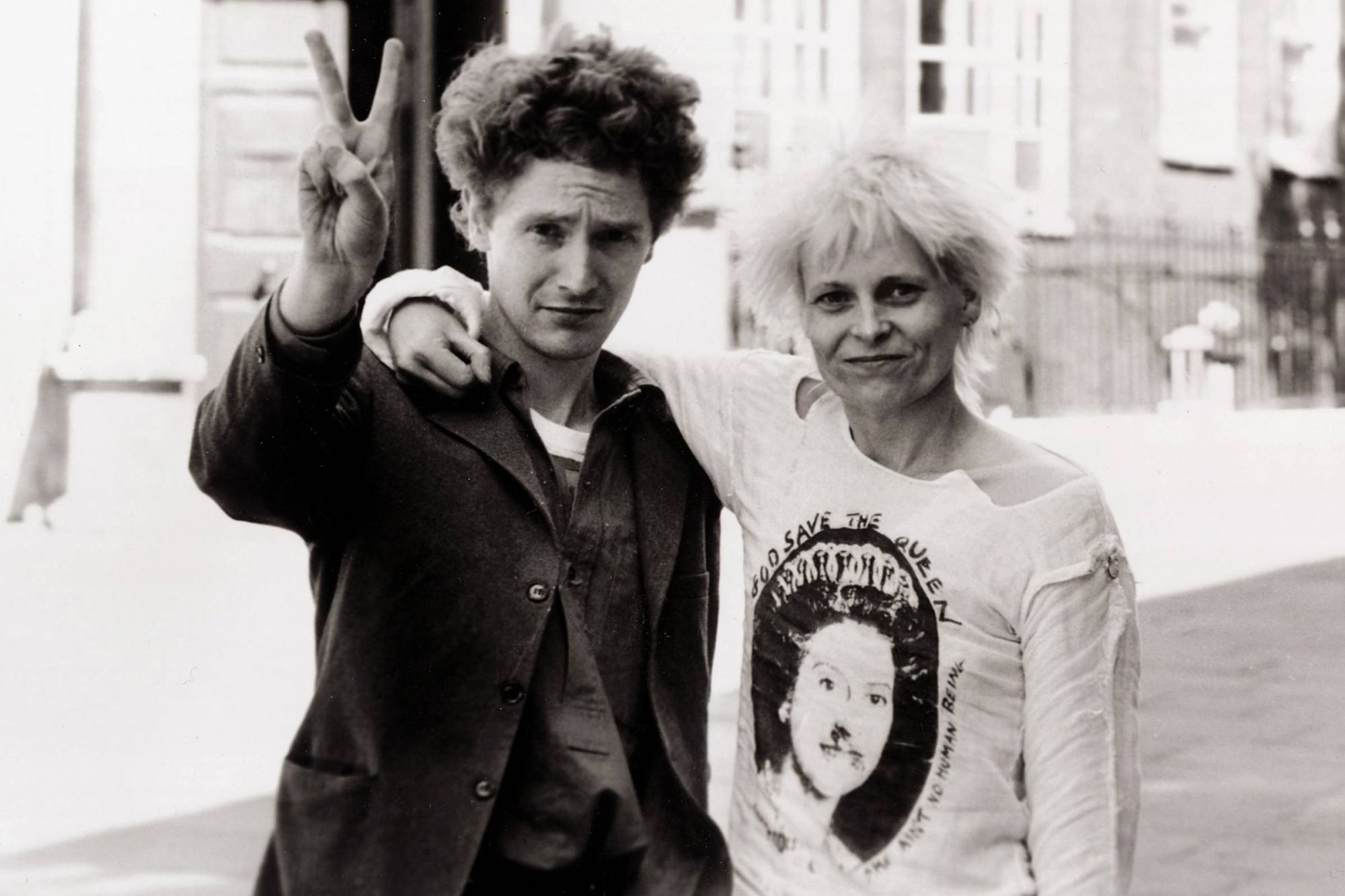

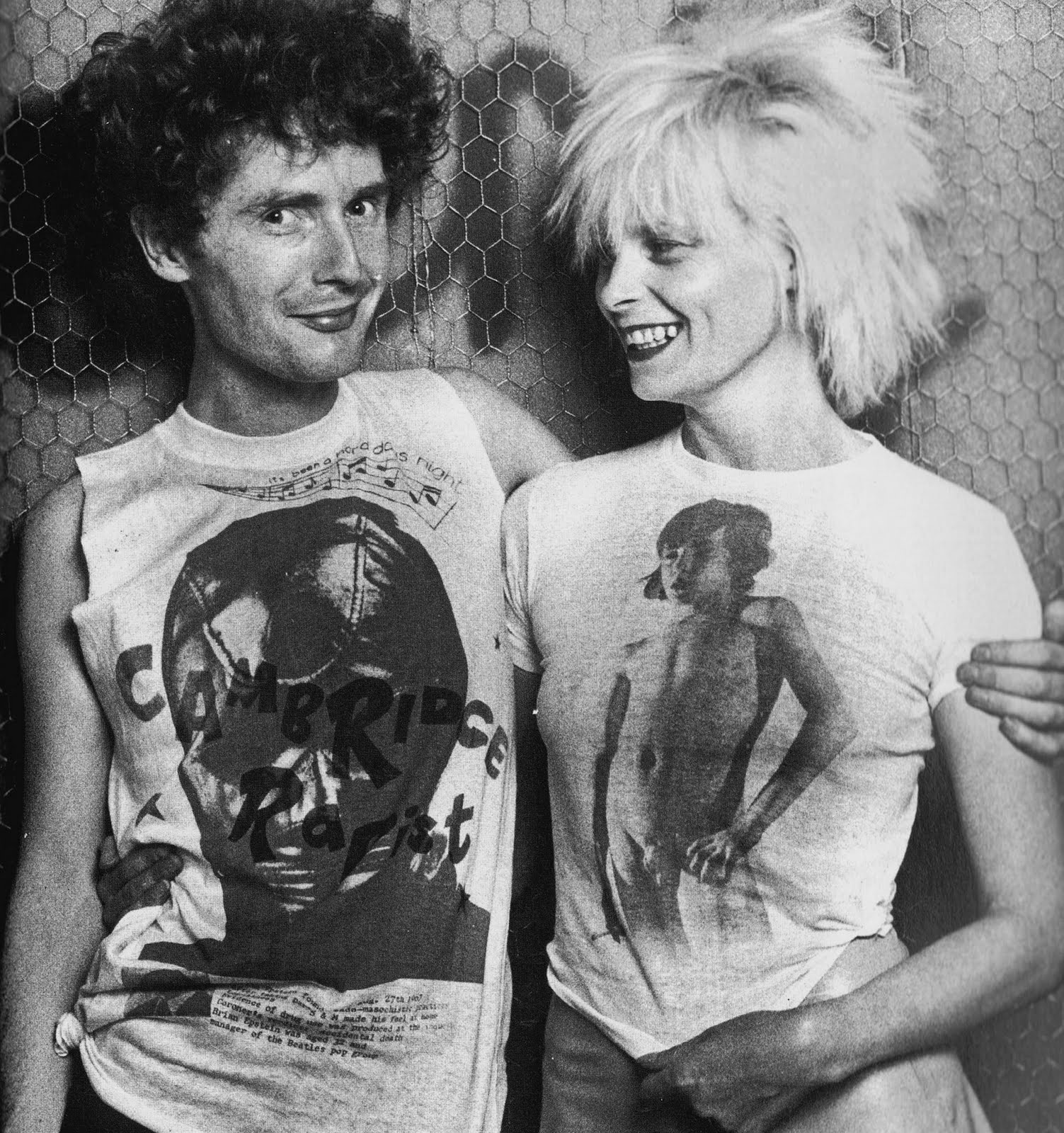

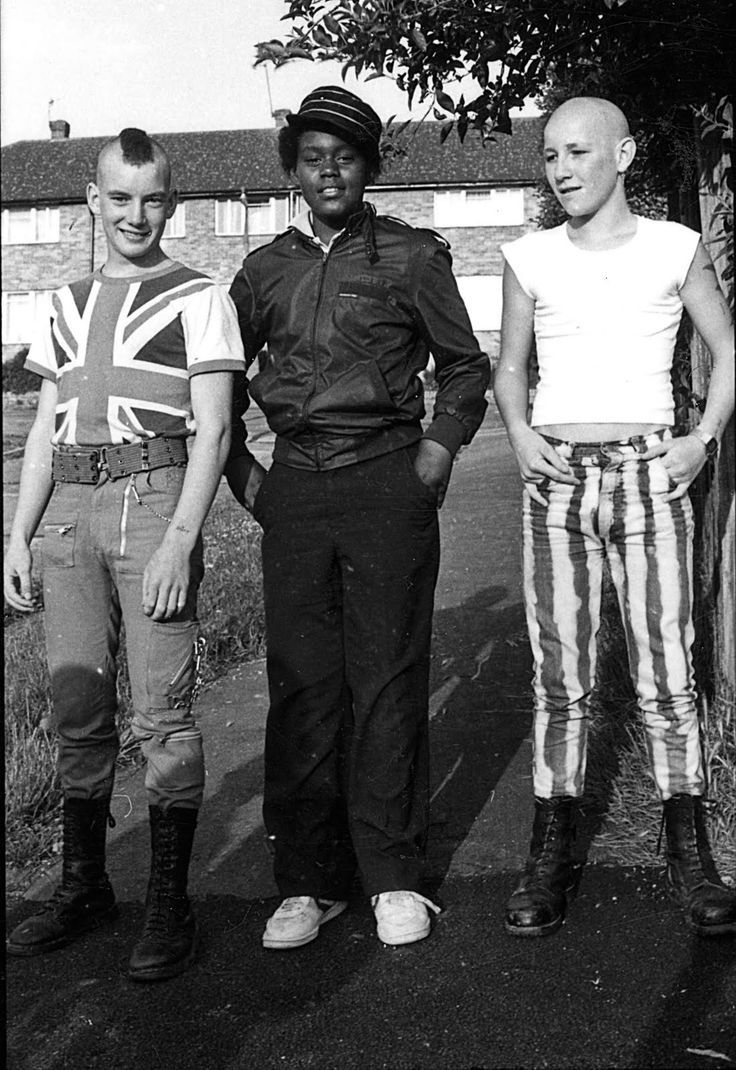

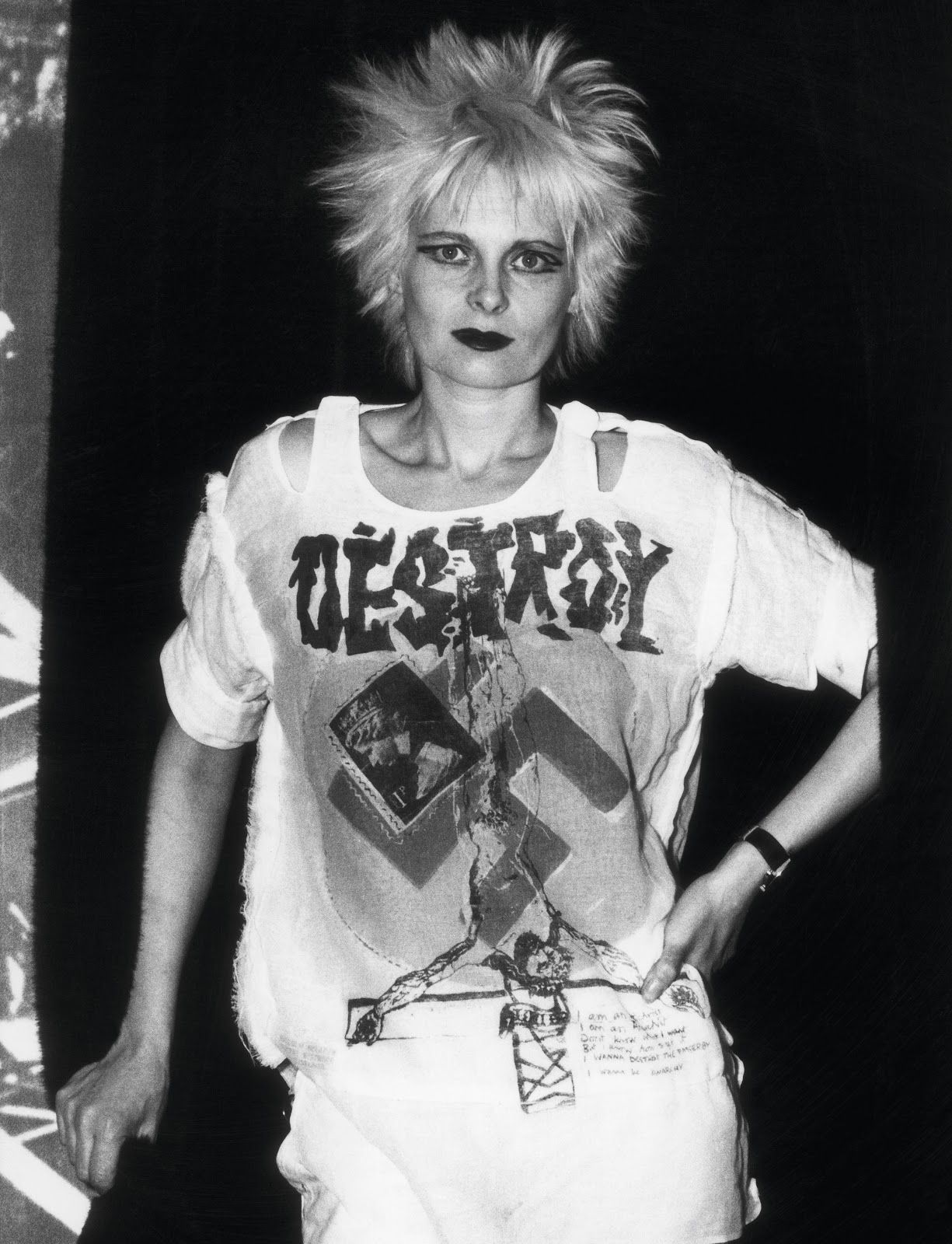

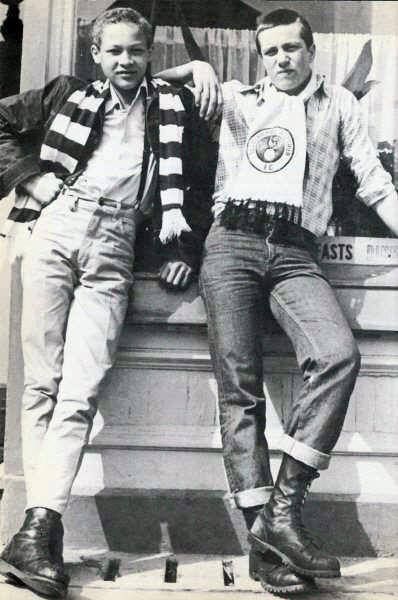

The t-shirt became a blank page on which to exhibit one's thoughts, political affiliation or aesthetic tastes. Each subculture ended up reinterpreting it in its own way: it appeared under the leather jacket of bikers, greaers and teddy boys; the beatniks tucked it into their tight jeans or under the lay shirts; hippies tinled her in psychedelic colors or printed messages of peace on it; skinheads alternated with polo poles, pairing it with the ubiquitous suspenders. Finally, the two creators of the punk aesthetic, Vivienne Westwood and Kathernine Hamnett, also made it one of the item-symbols of countercurrent design. Hamnett herself wore one when she met Margaret Tatcher in 1984.

The modern streetwear

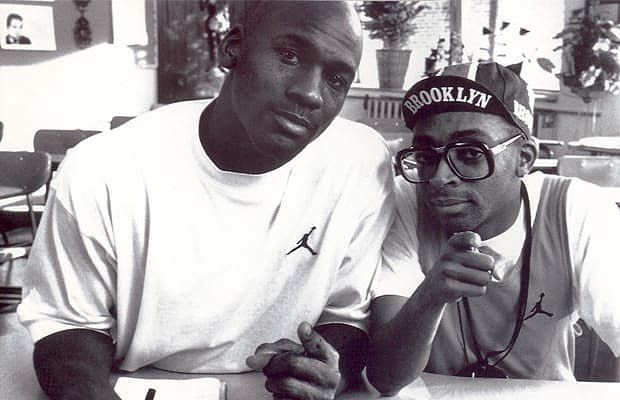

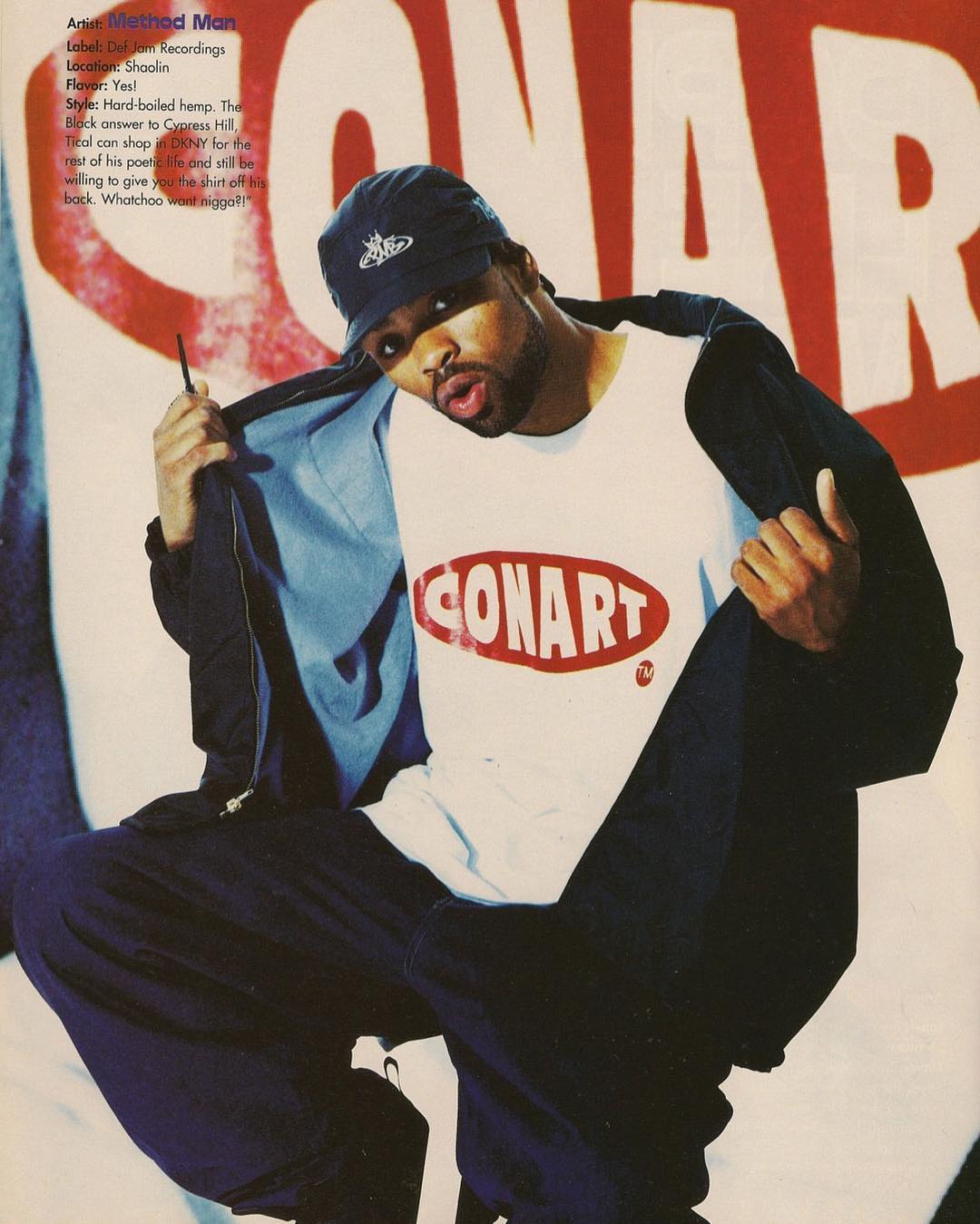

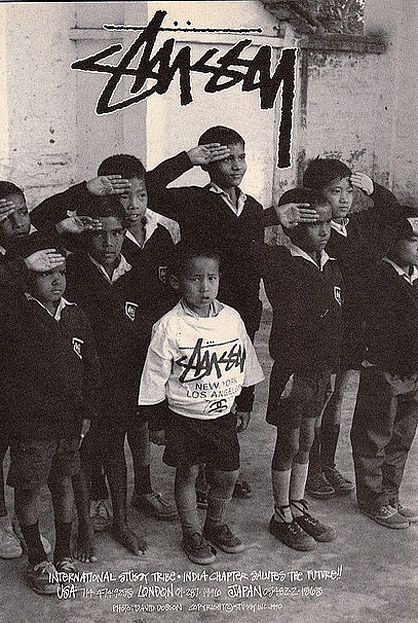

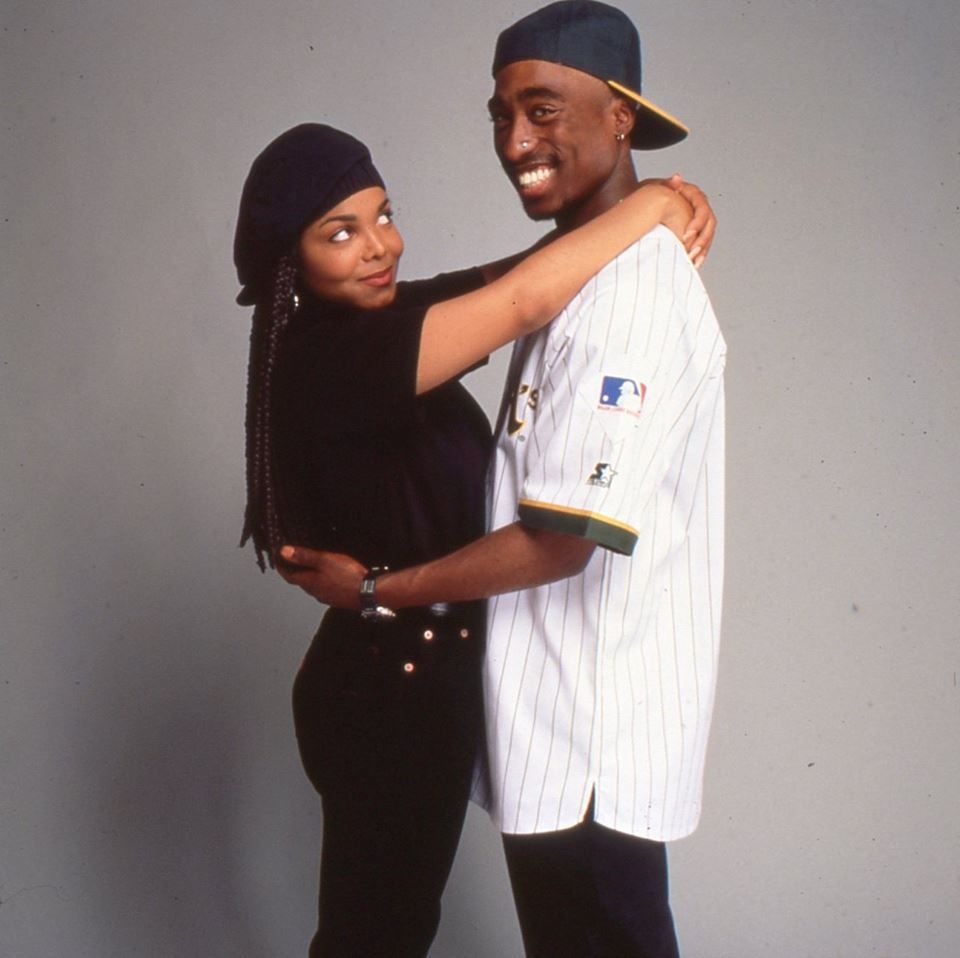

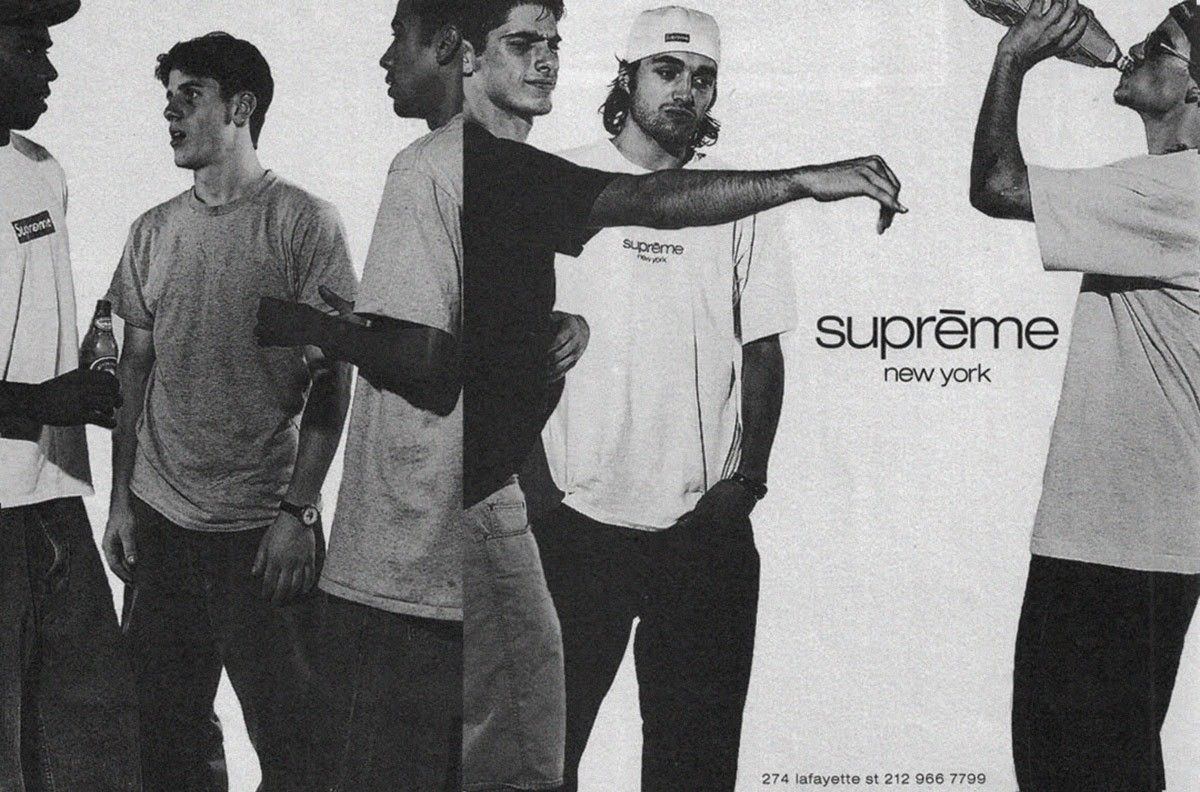

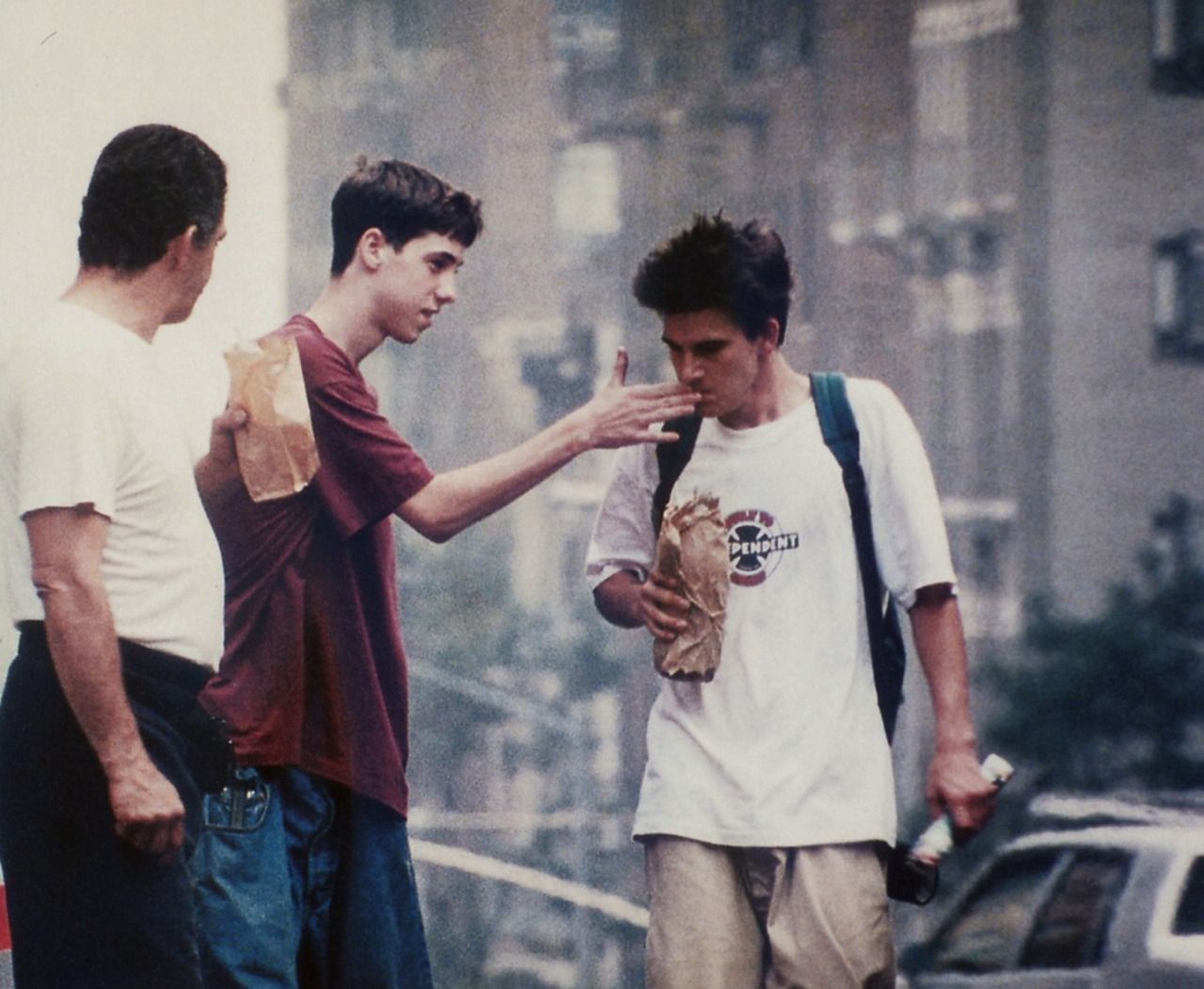

Between the late 1980s and early 1990s, then, with the emergence of brands such as Supreme and Stussy, whose aesthetics are moved precisely by all that informal clothing that the younger generations had begun to wear, the white T-shirt, variously decorated, went from the seriousness of civil protests to the most light-hearted pop culture: Supreme's Box Logo Tee and the first t-shirts decorated by Shawn Stussy are the perfect example of this cultural shift. These first streetwear brands were the heirs of Westwood and Hamnett, because they resumed the use of the t-shirt as a blank page filling it not with subversive messages but with references to other logos or to the world of pop culture - bringing intertextuality within the street culture.

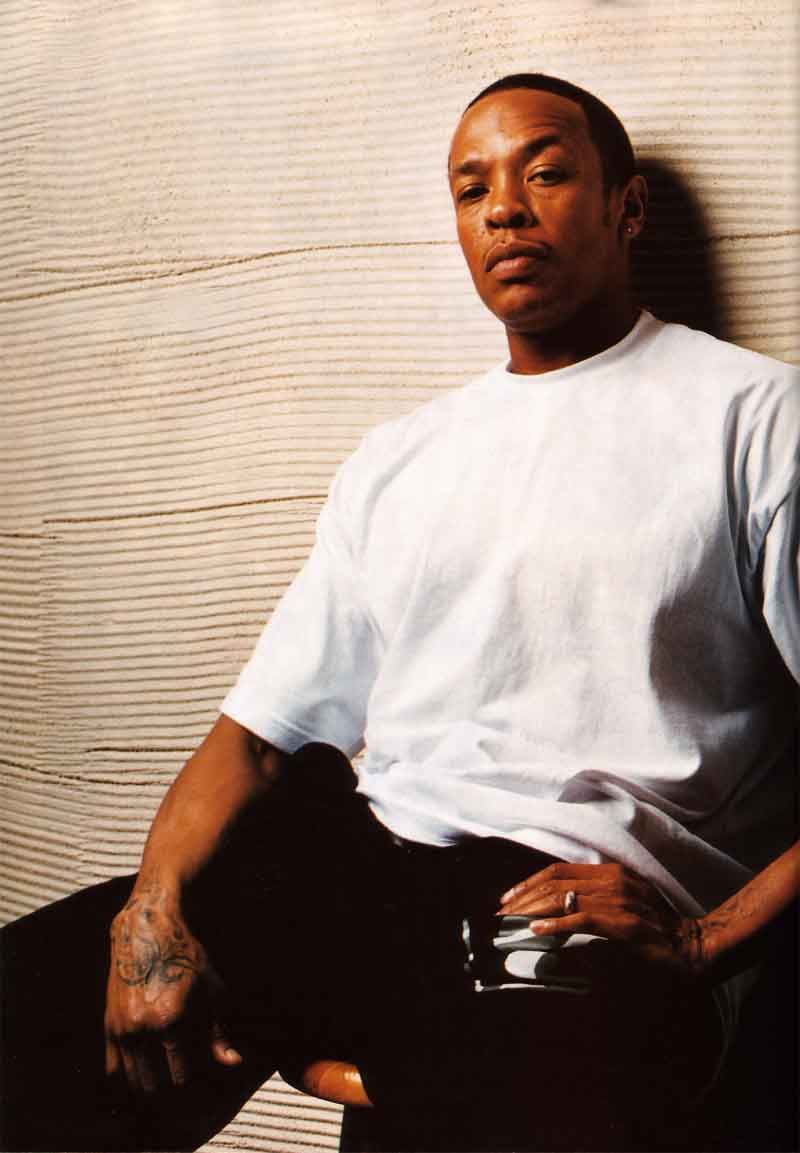

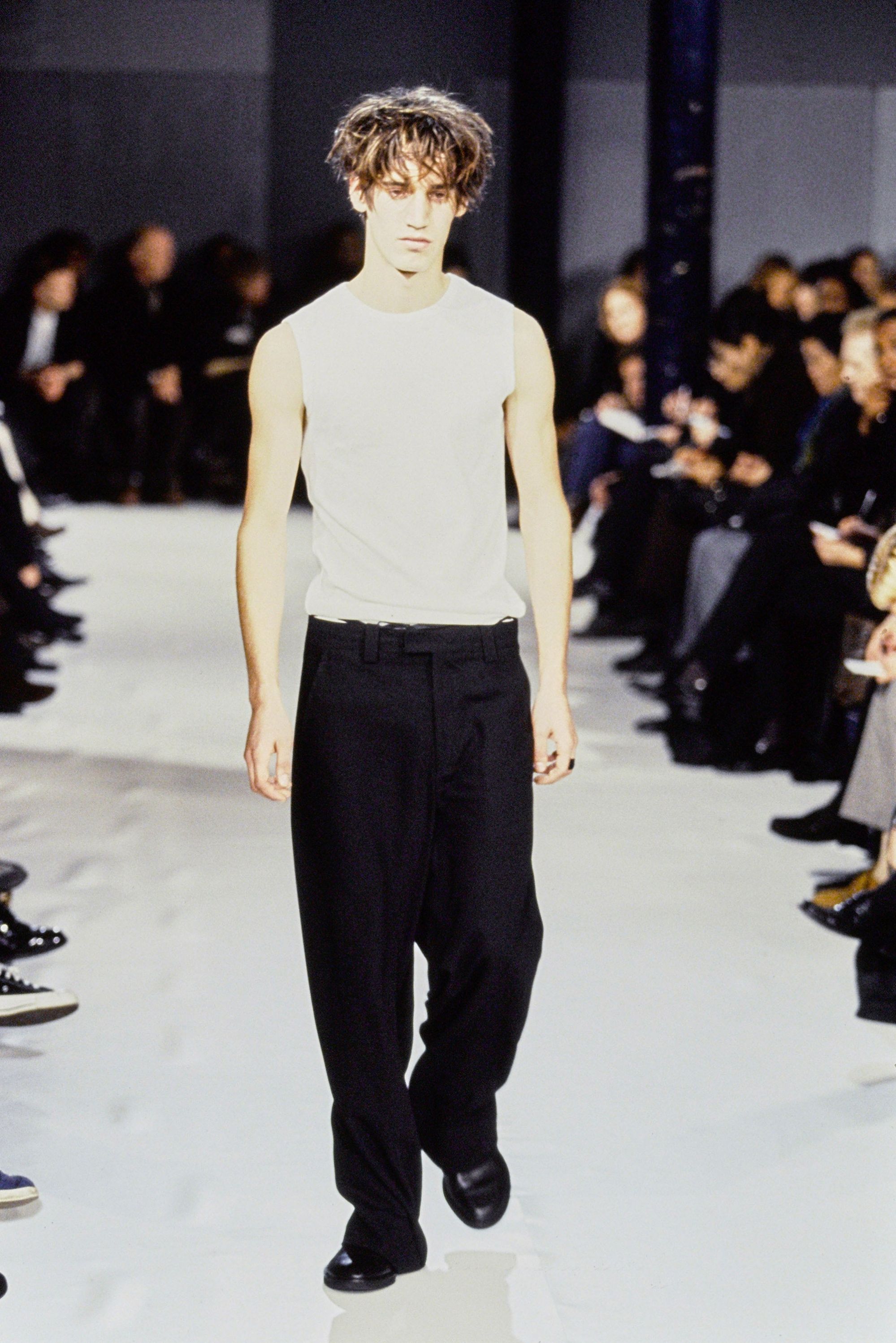

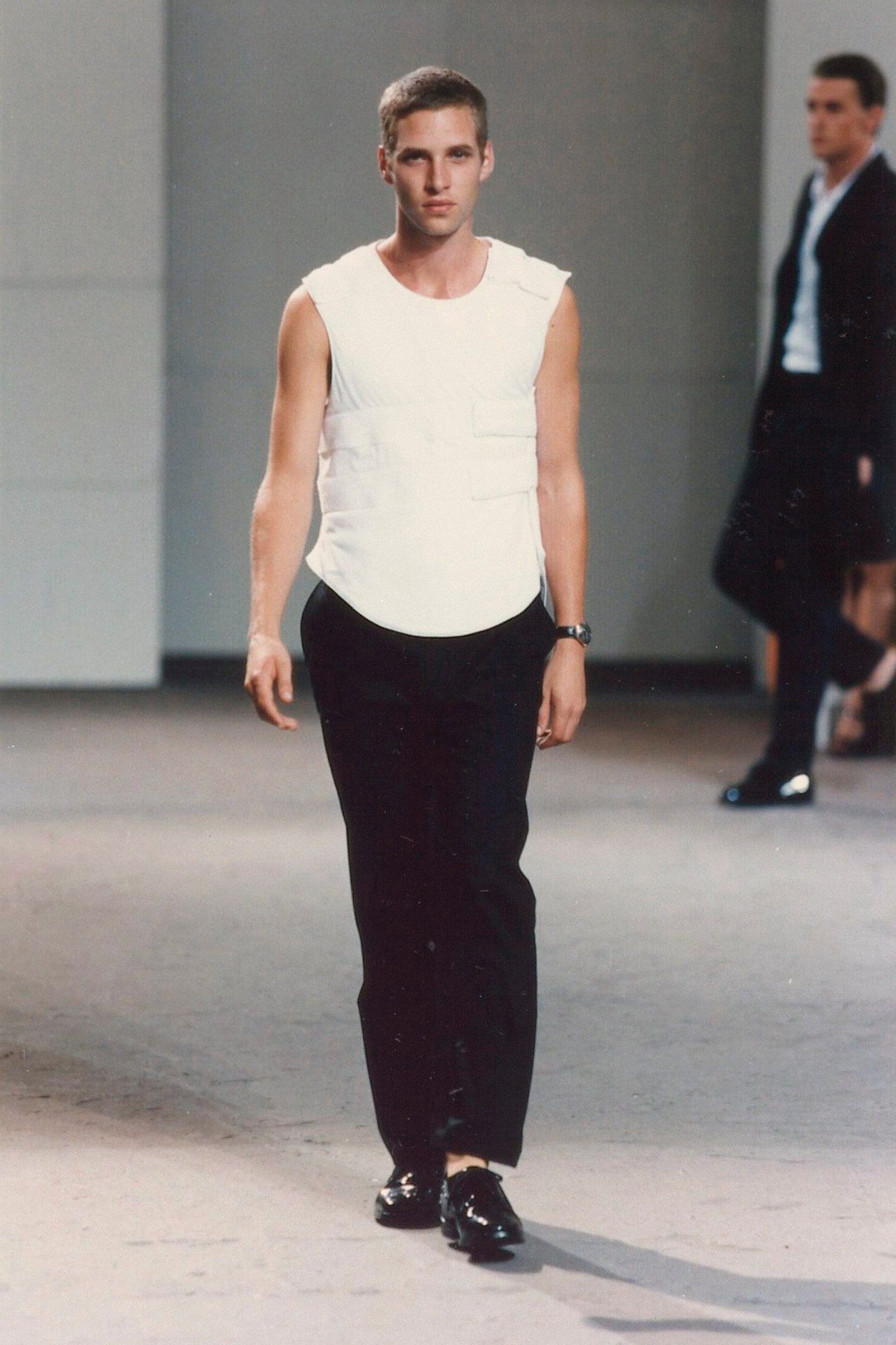

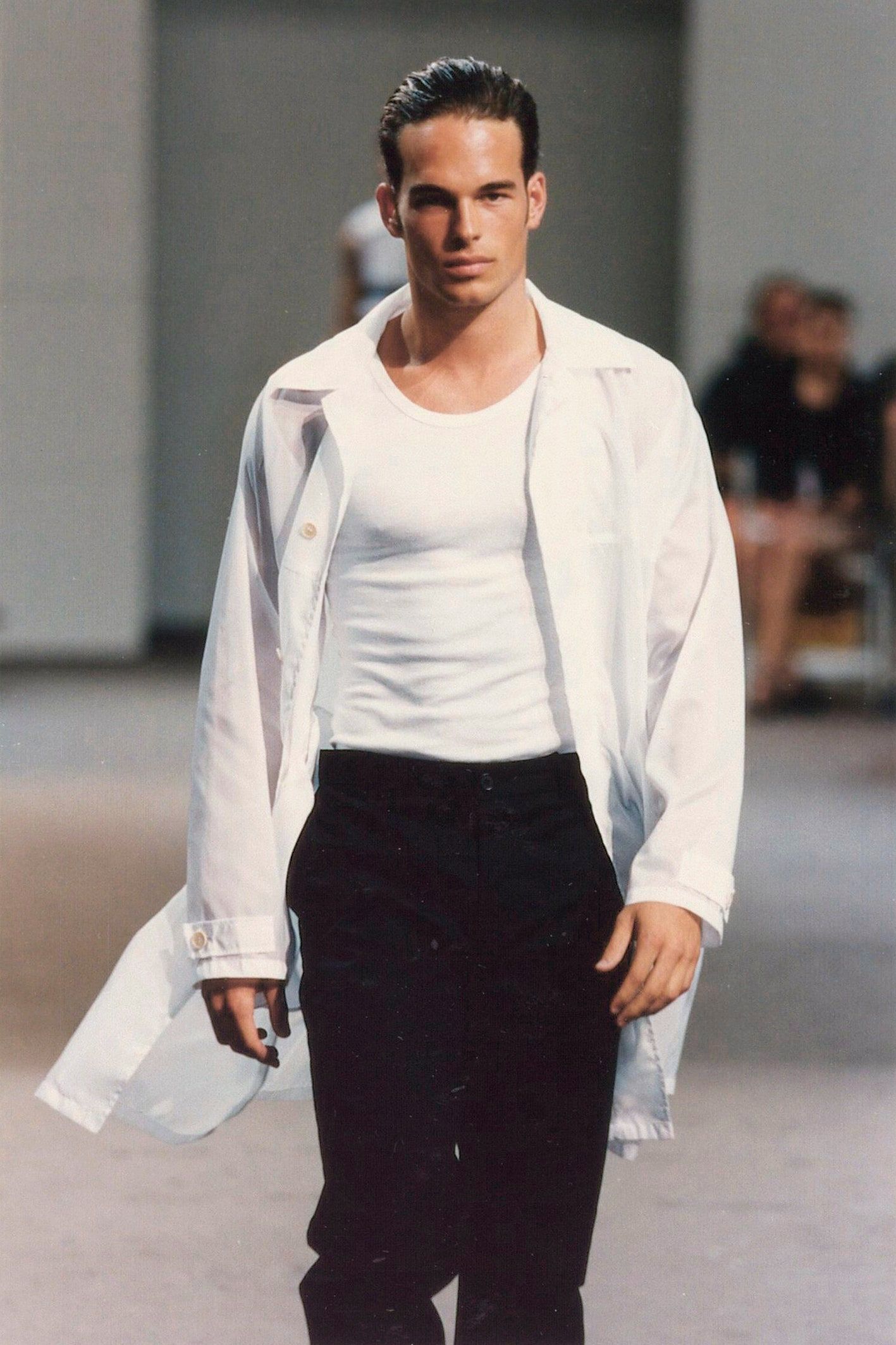

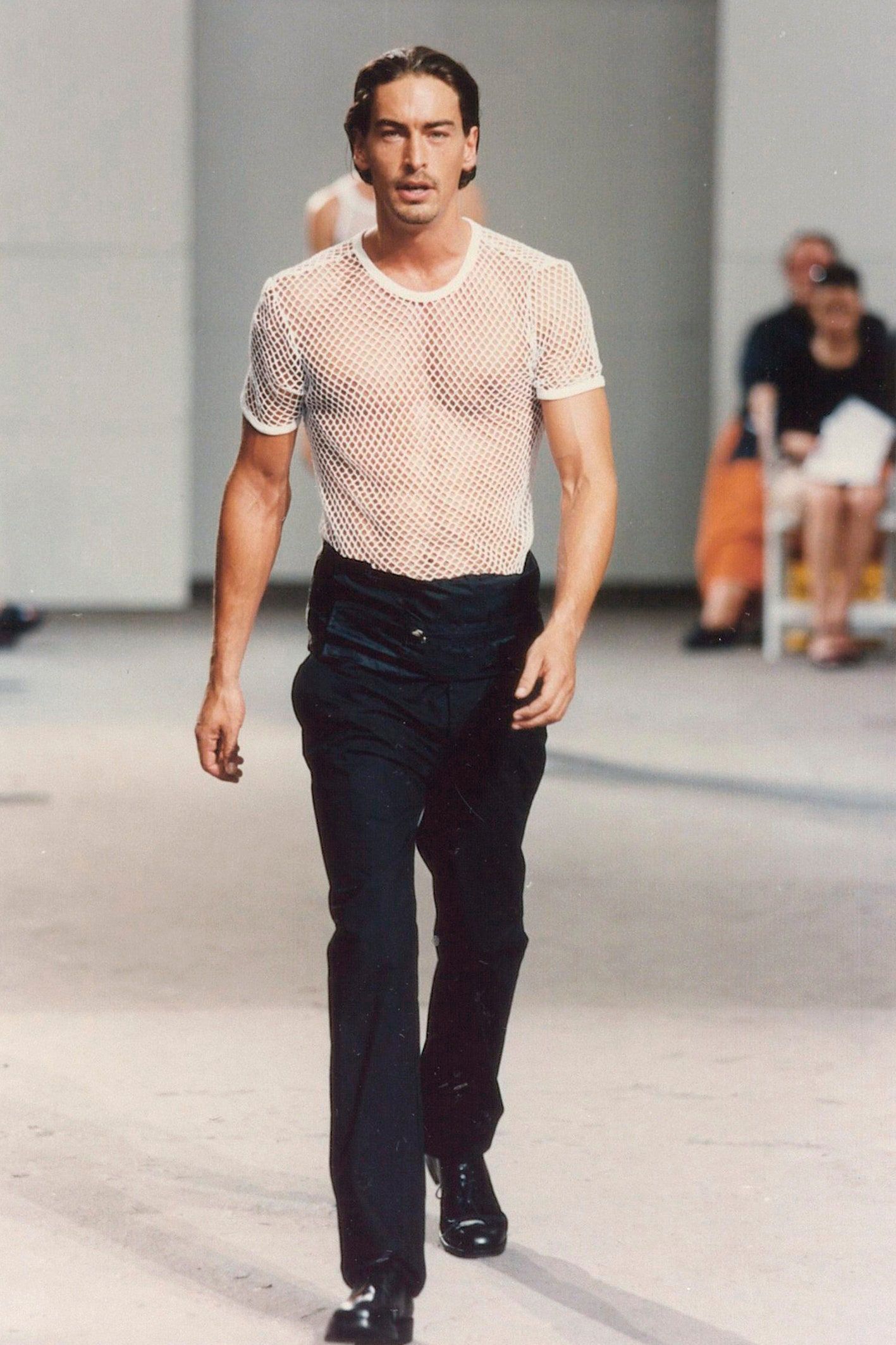

In short, American luxury brands such as Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger also began to produce more high-end versions, while in Europe, minimalist designers such as Ann Demeulemeester and Helmut Lang made it a tool for studying pure fit, ennobling its image from a design point of view.

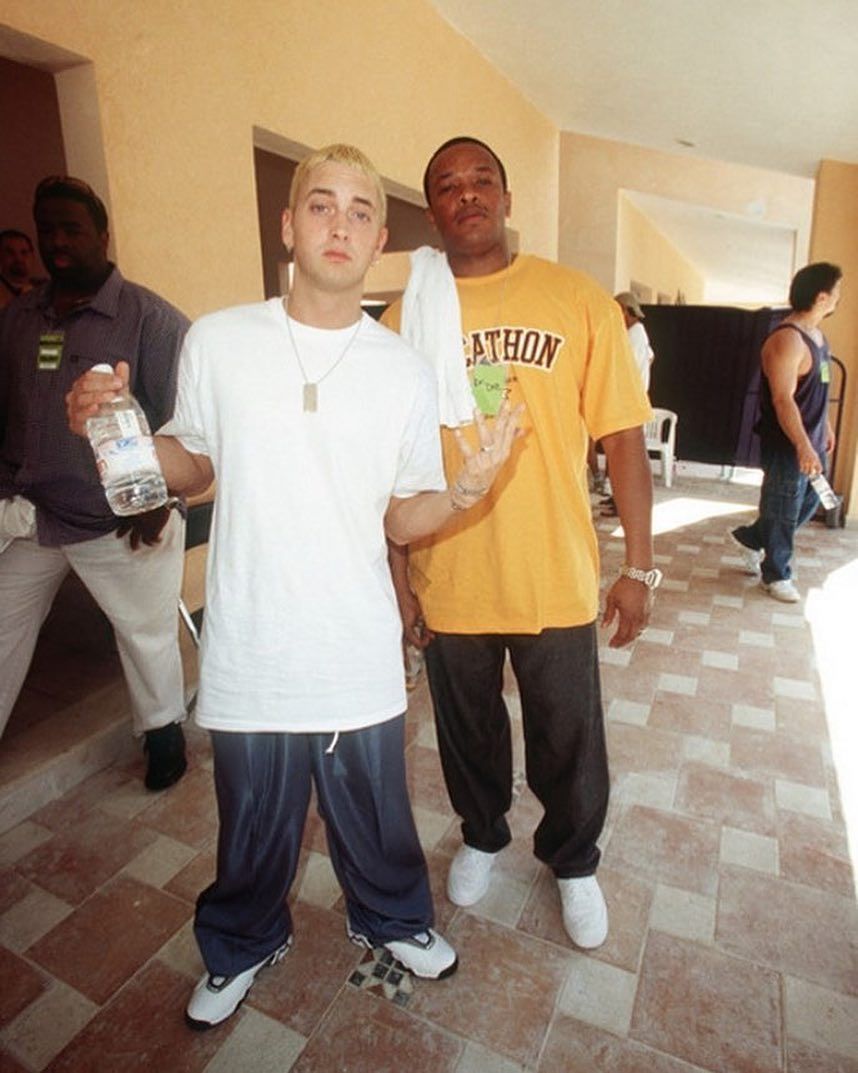

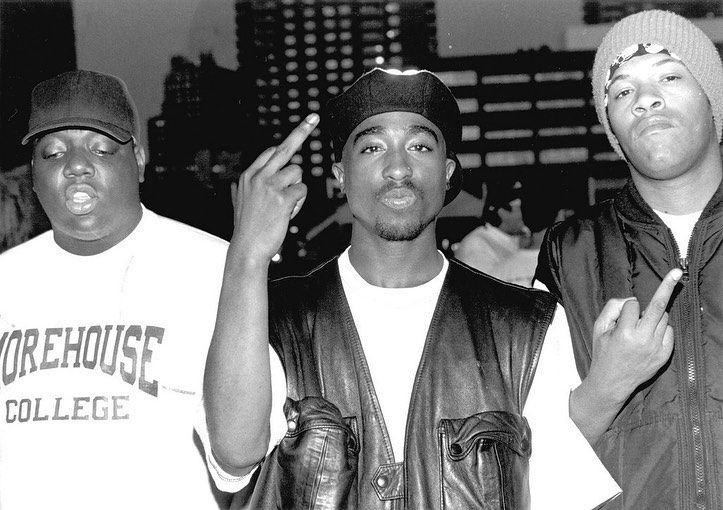

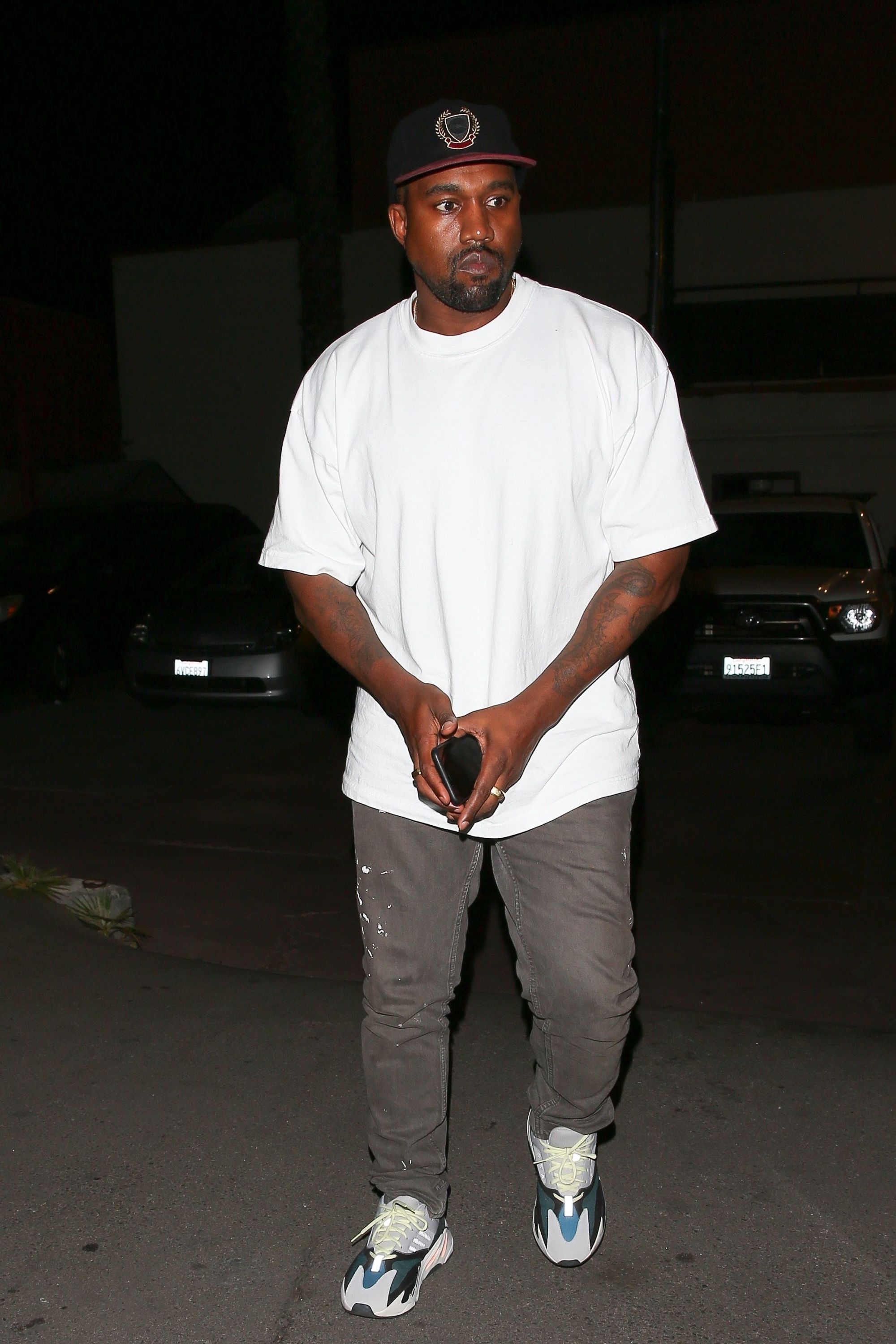

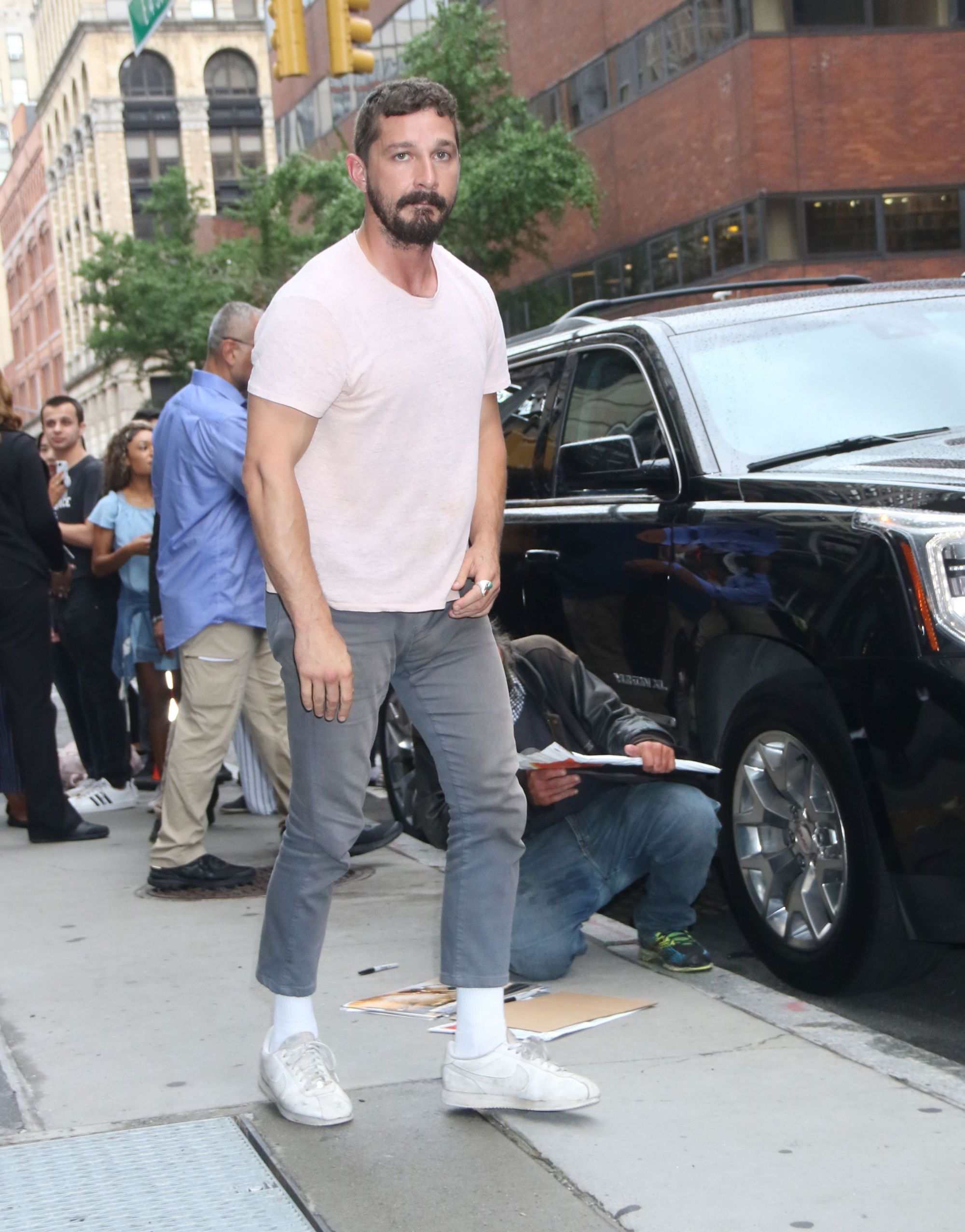

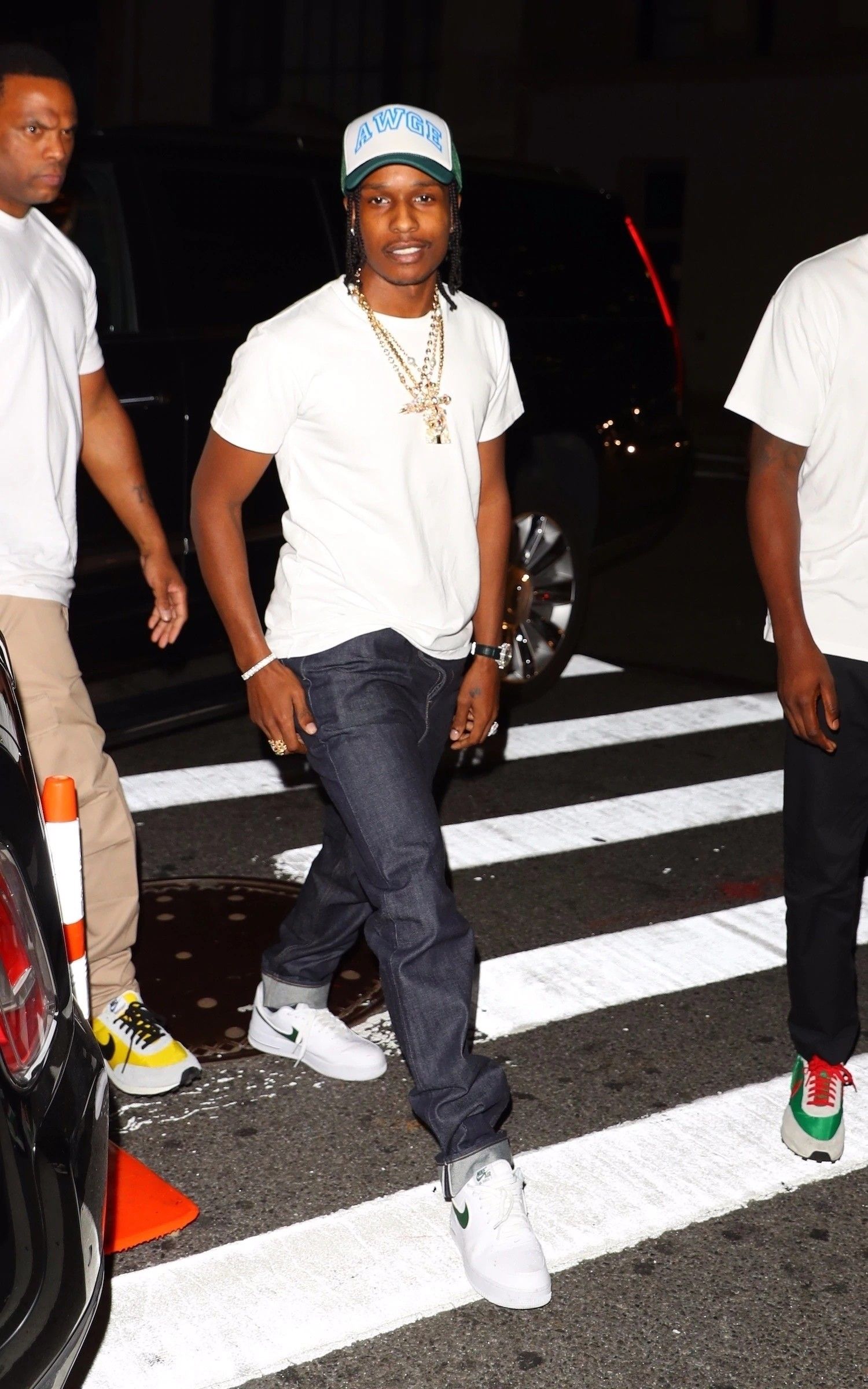

Past the millennium horizon, the white t-shirt took two directions. On the one hand there was the continuation of the urban subcultures of surfers, skaters and rappers, that youth already immortalized in the 90s by Larry Clark in Kids, with oversized fit and maximalist graphics. On the other, there were the art students of the East Village and Williamsburg, the so-called hipsters, the first agents of gentrification, who raised a cult to the vintage t-shirt and V-neck for men. Later the two worlds attenuated their more radical characteristics with hip-hop that began to dialogue with fashion abandoning the most exaggerated baggy forms and the style of hipsters who lost their extravagances to become the current normcore - a term born after a famous reportage of the New York magazine K-Hole who wrote:

“Once upon a time people were born into communities and had to find their individuality. Today people are born individuals and have to find their communities. […] Normcore knows the real feat is harnessing the potential for connection to spring up. It’s about adaptability, not exclusivity.”

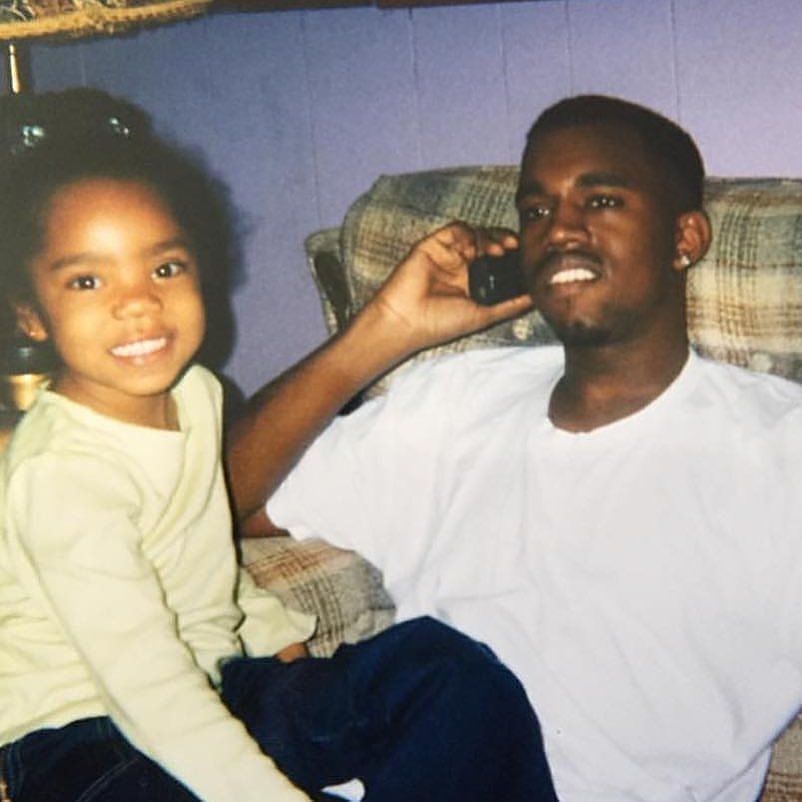

In the late 2010s, finally, the two aesthetics mingled with the definitive combination of fashion, streetwear and hip-hop culture. Style and function became one, and hipsters no longer needed a V-neck to prove their originality just as hip-hop singers didn't need XXL outfits to witness their realness. The various styles found a synthesis and opened up to greater eclecticism: singers began to design clothes, collaborate with large fashion houses and accept women and LGBTQ minorities in their ranks - the world of cultural references expanded beyond measure but became an increasingly common ground. As a result, a synthesis soon came between a more high-end style and the disengaged daily style. Jerry Lorenzo and Kanye West, and their respective brands, are the perfect example of this trend that, over the next ten years, will almost certainly find its decisive symbol in the collaboration between Yeezy and Gap - that is, the moment when one of the leading exponents of contemporary hip-hop culture, Kanye West, will devote himself to the creation of a line of high democratic basics and open to all with in mind the vision of the birth of a new cross-party icon. Fashion.