The incredible history of KAPITAL Japan We look back at the history of the brand, on the day of the founder's passing

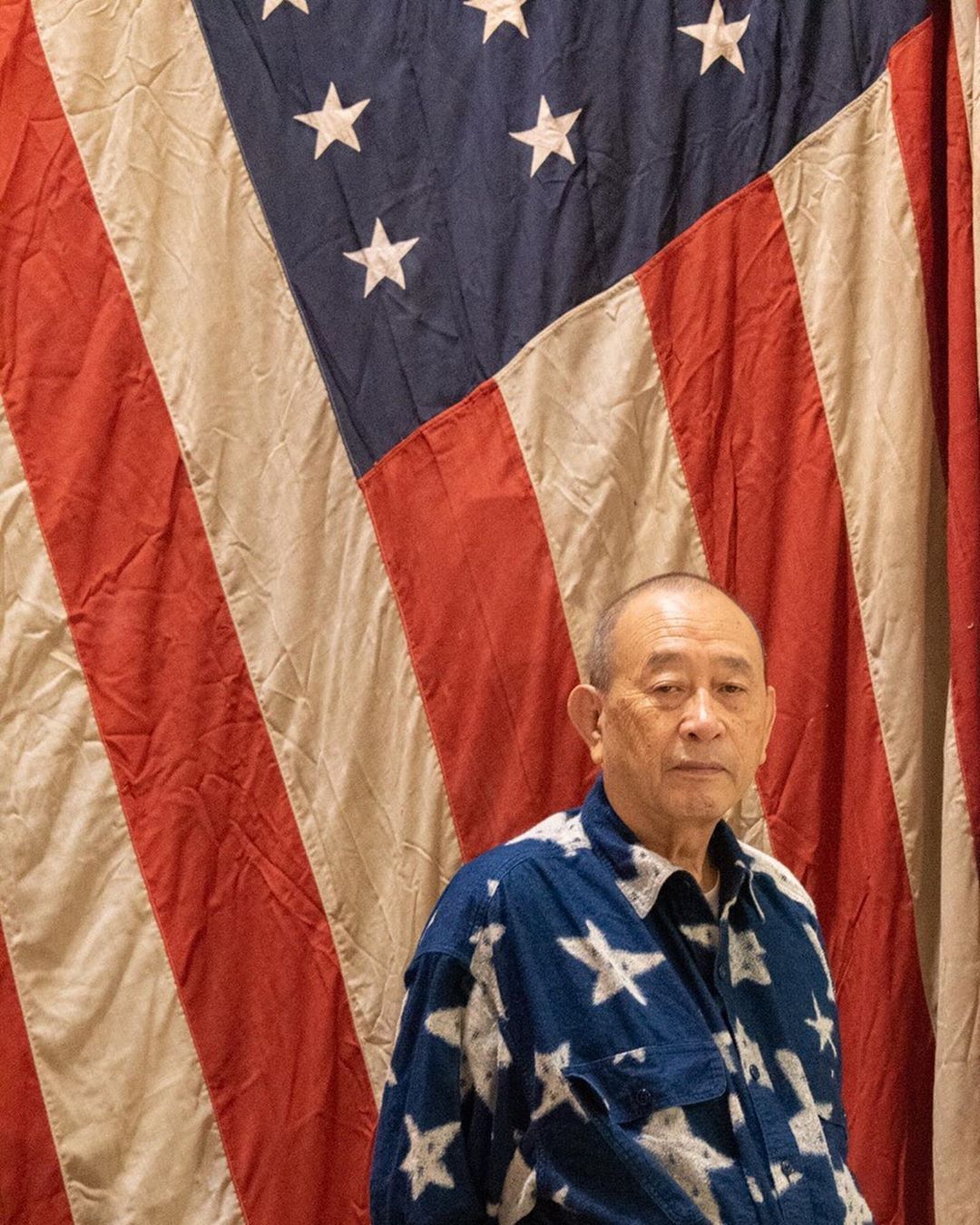

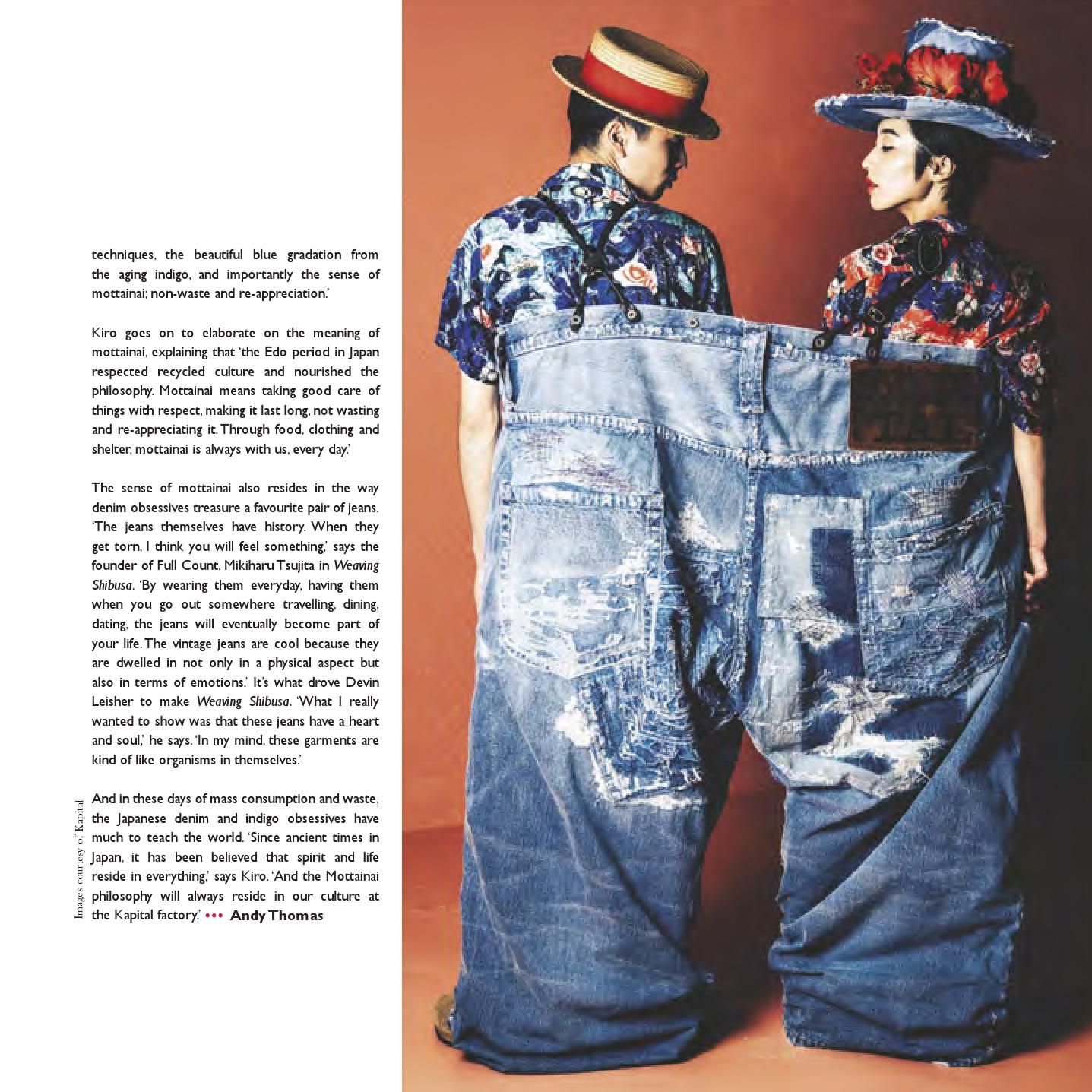

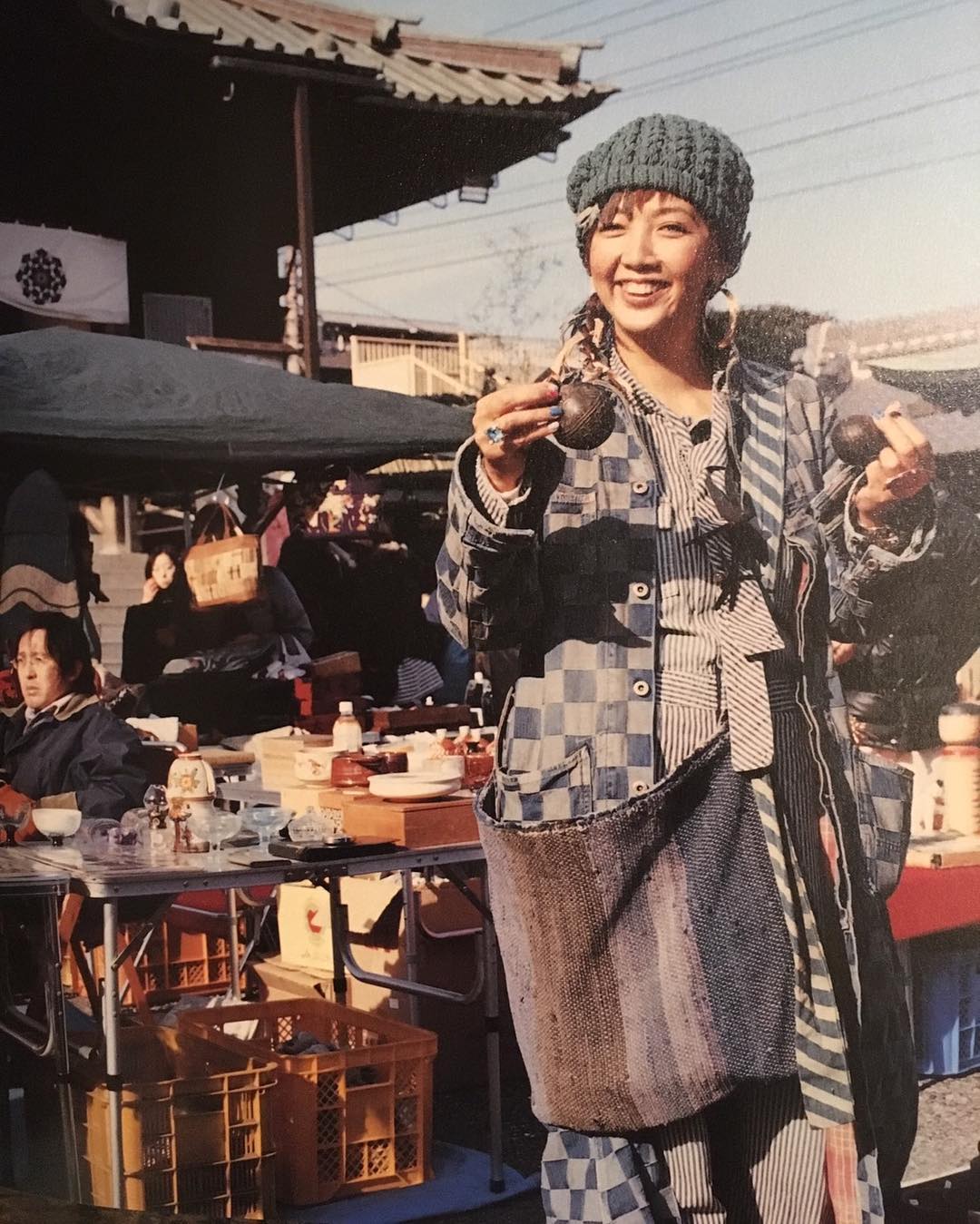

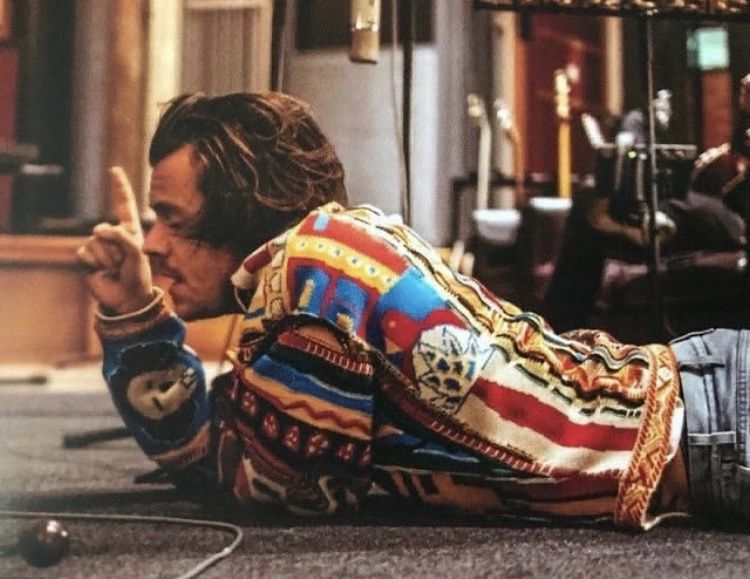

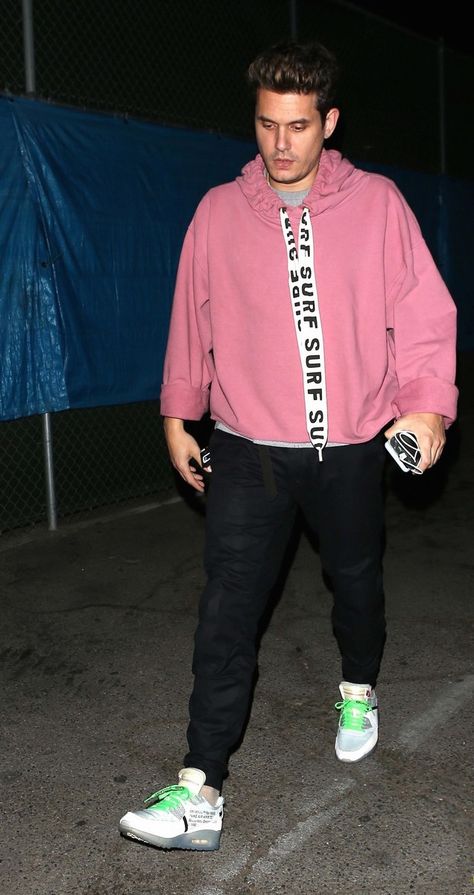

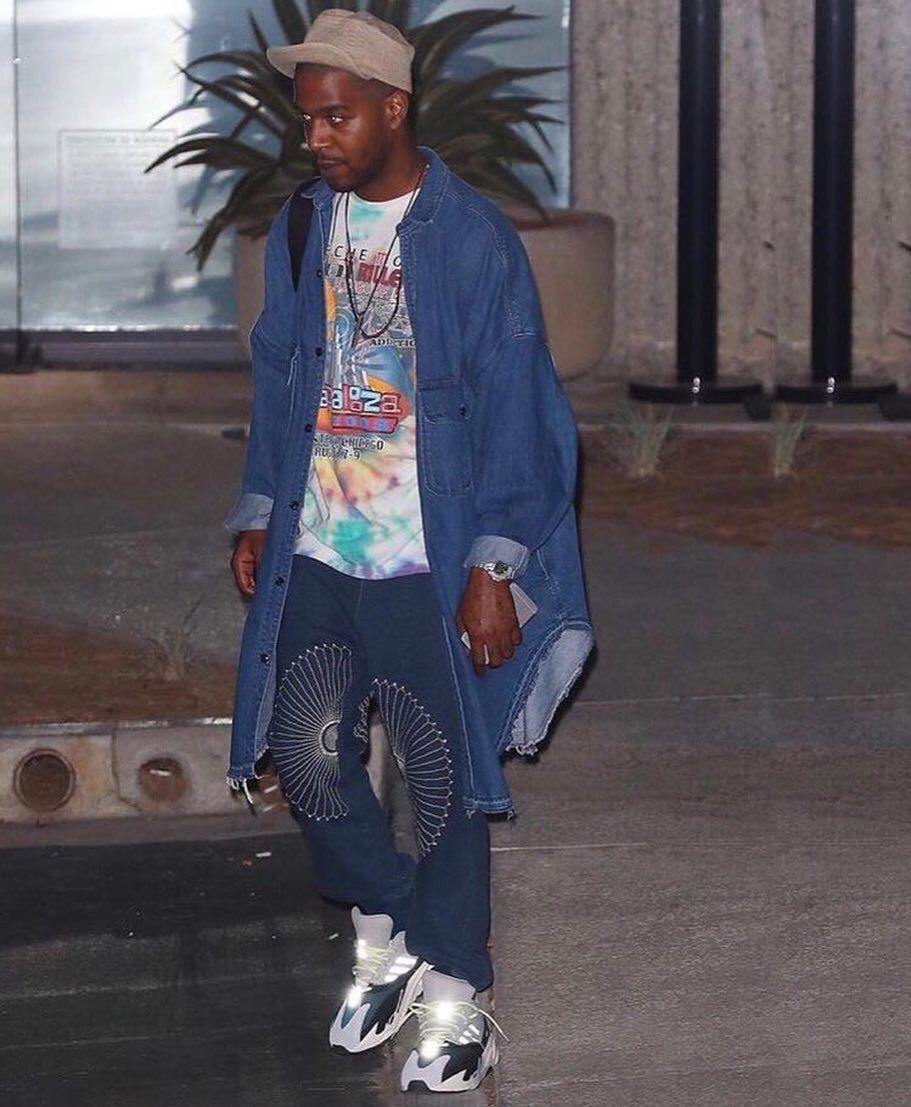

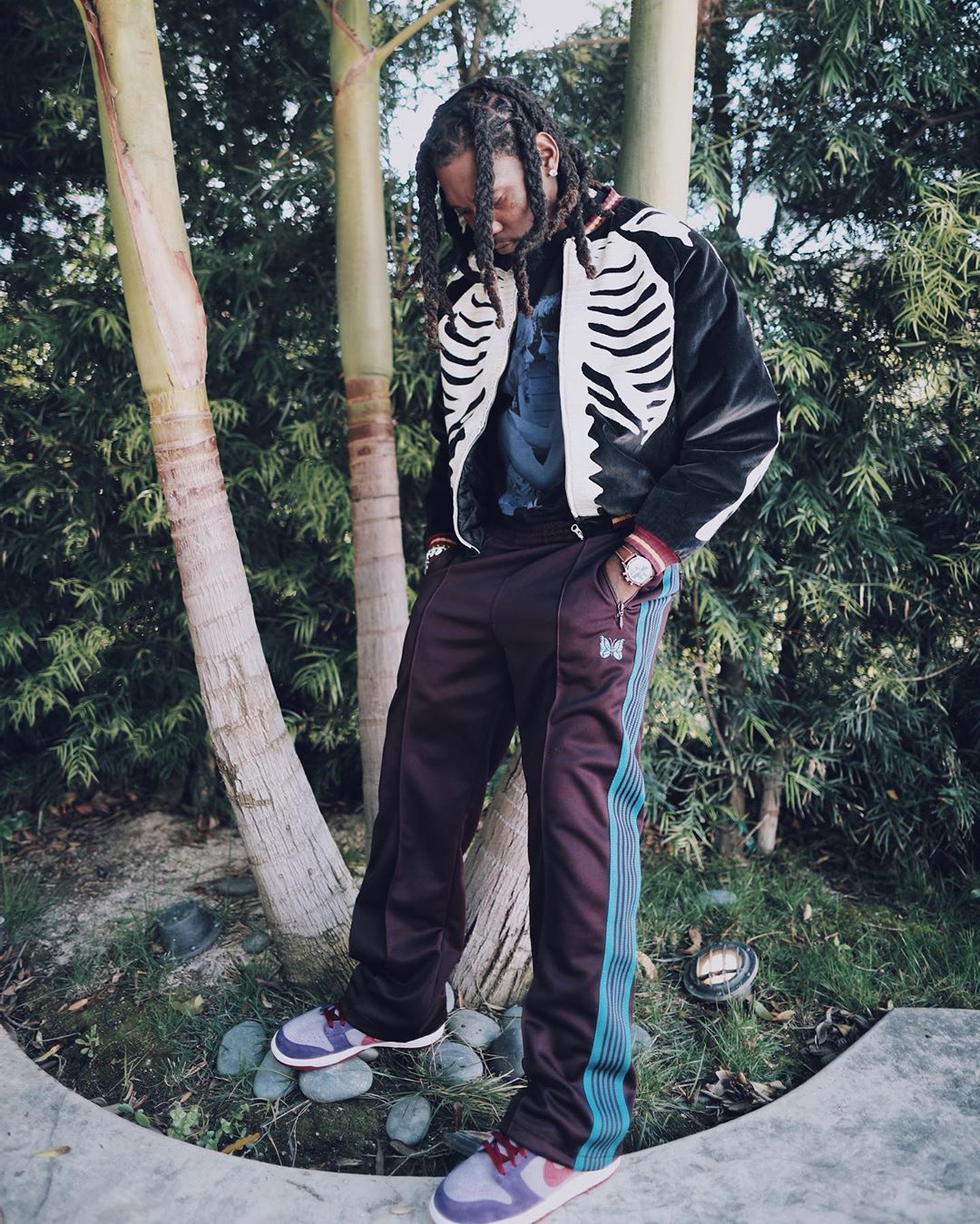

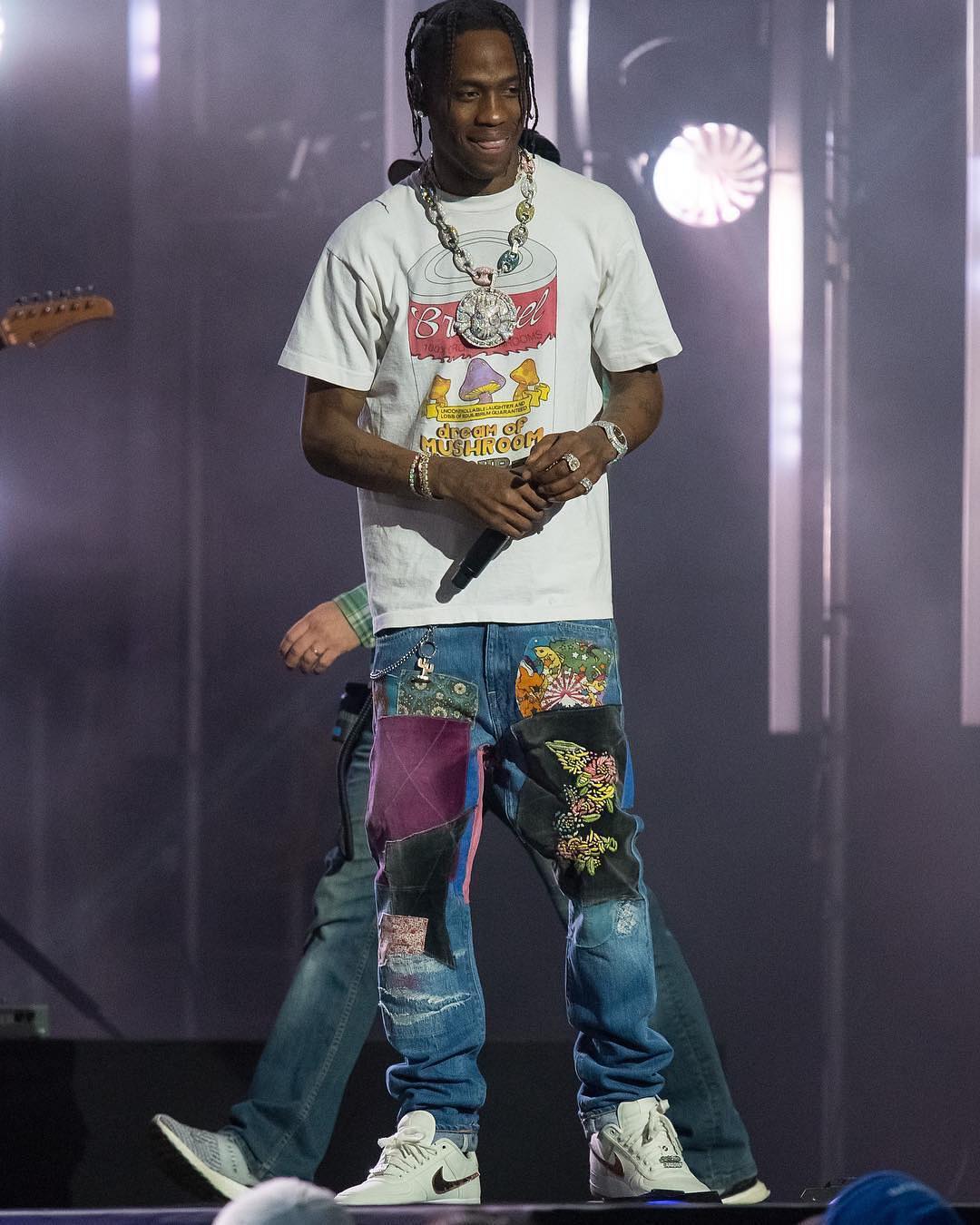

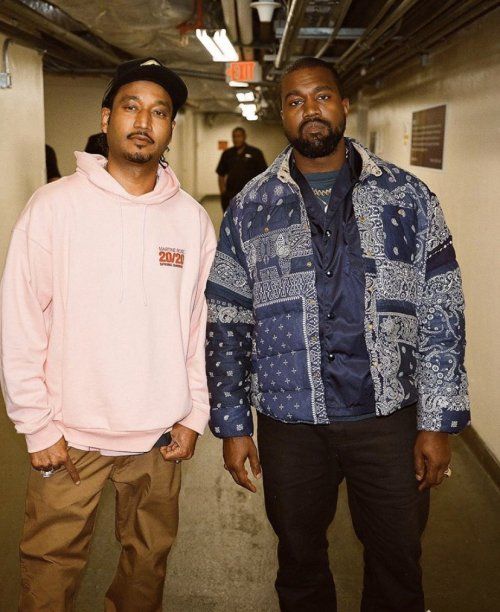

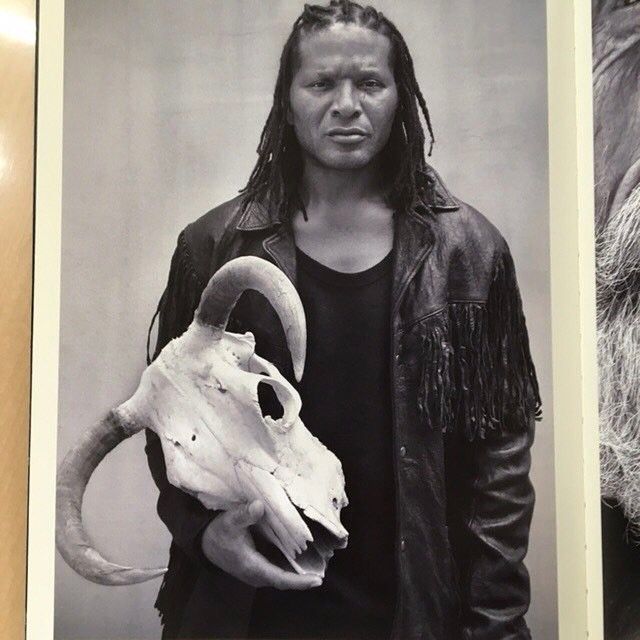

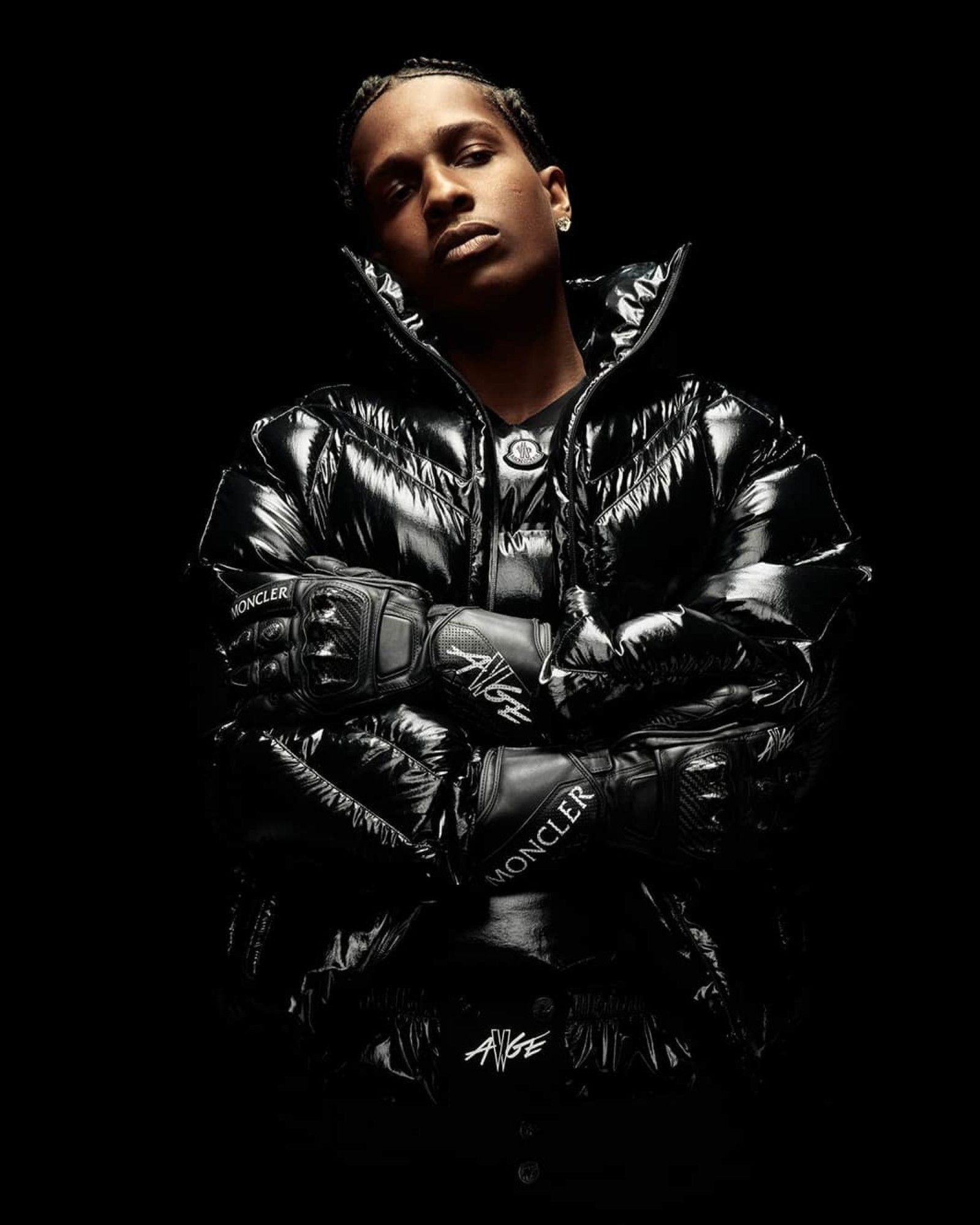

«Denim. That is my philosophy».These were the words of Kazuhiro "Kiro" Hirata, creative director of Kapital, when Noah Johnson interviewed him for GQ five years ago. A word that expresses well the essence of a brand that knows no more words. Currently Kapital has become the ultimate brand in that diverse universe that is Japanese denim – a universe that has its center in the city of Kojima, which has risen to this role of great importance after, with the spread of American fashion among the youth following the post-war occupation of the USA in Japan, its textile factories specialized in uniforms and workwear converted to denim factories to follow the new business opportunity , being in a unique aesthetic coincidence between workwear materials and Japanese craftsmanship.Today, a piece of that history has come to an end with the announcement of the passing of the founding father of this cult brand, Toshikiyo Hirata, who was among the leading creators of denim to bring back into vogue the boron-stitching technique for which Kapital has become famous and who was part, as one of its most prominent members, of that legion of Japanese entrepreneurs and designers who created the "Japanese Americana" style. Specifically, Kapital distanced himself from other denim producers for its edginess: a tortured and structurally complex aesthetic, but not without pop elements, which attracted rock and hip-hop musicians such as A$AP Rocky, Kanye West, Travis Scott, Pharrell, Harry Styles and John Mayer, among others.

Writer and humorist David Sedaris described the brand's aesthetics ironically and yet accurately in an essay published four years ago in The New Yorker:

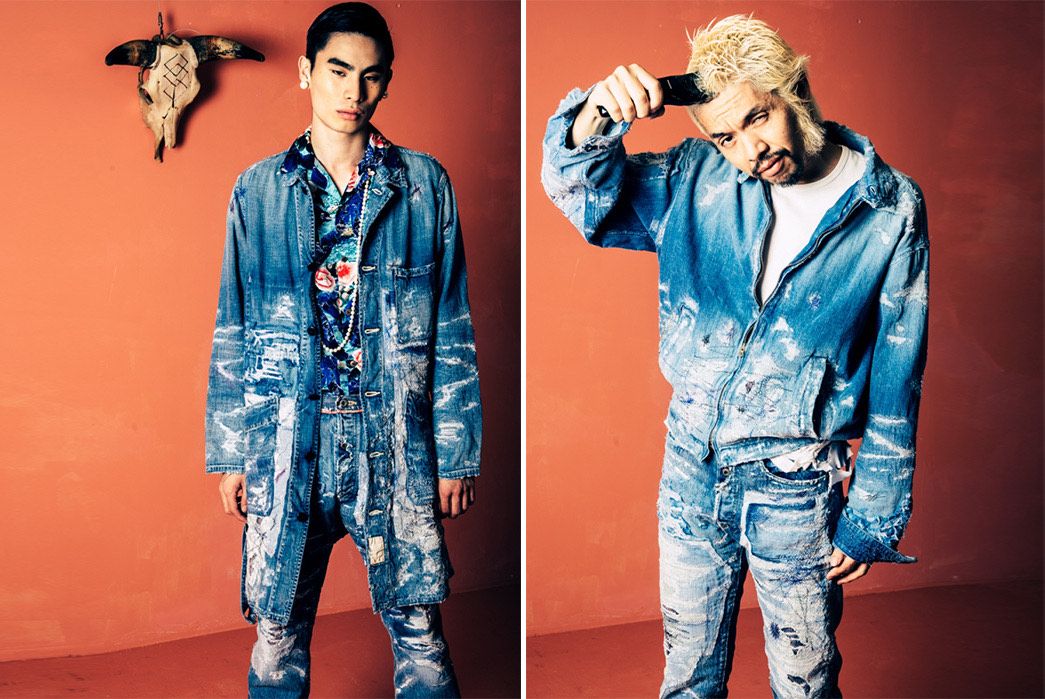

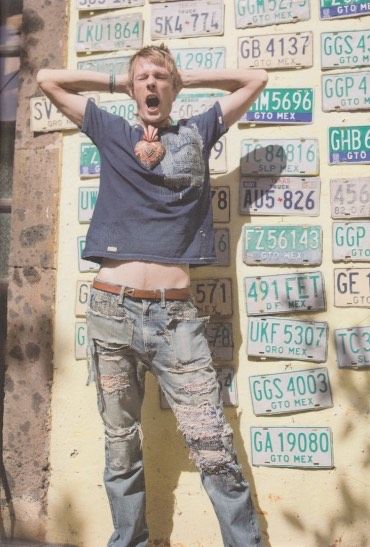

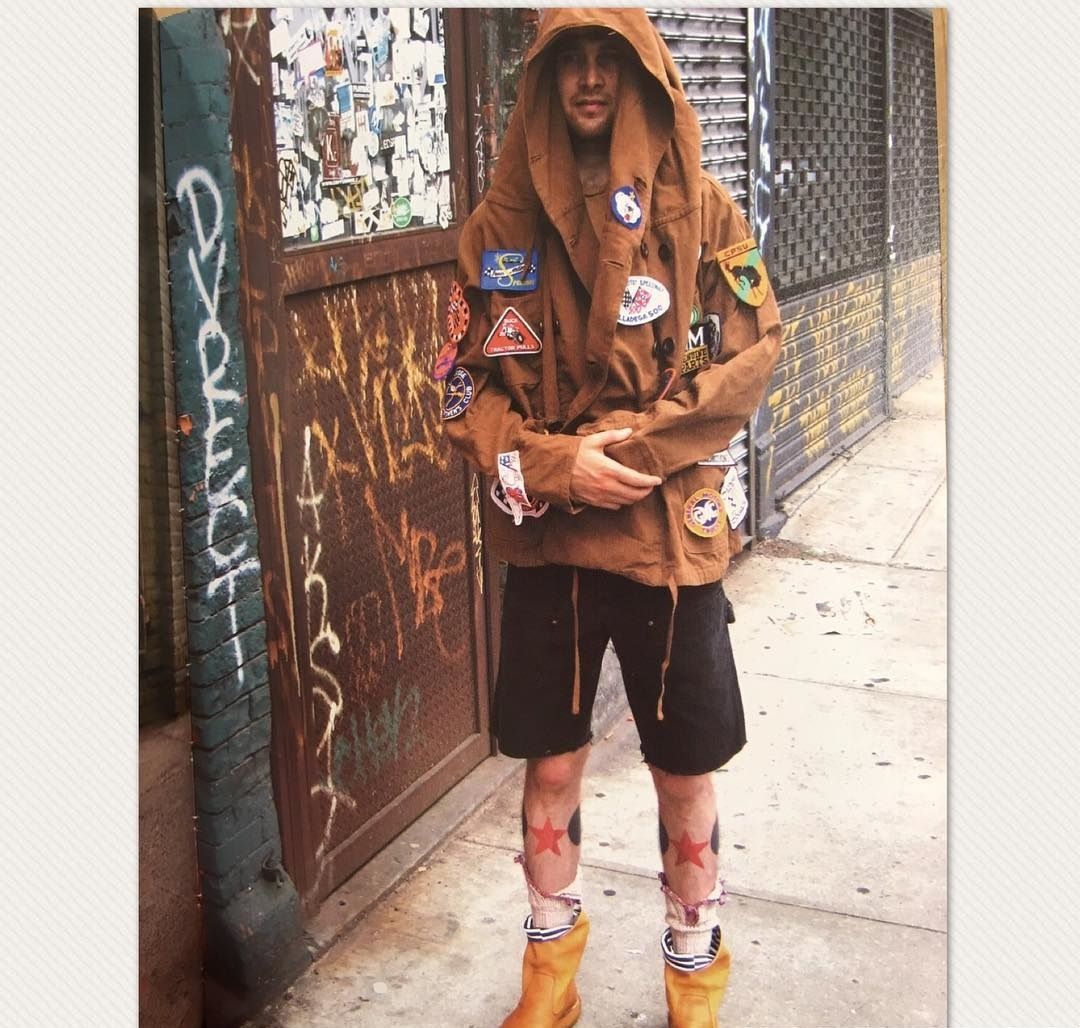

«The clothes they sell are new but appear to have been previously worn, perhaps by someone who was shot or stabbed and then thrown off a boat. Everything looks as if it had been pulled from the evidence rack at a murder trial. […] Most distressed clothing looks fake, but not theirs, for some reason. […] How do they get the cuts and stains so... right? If I had to use one word to describe Kapital’s clothing, I’d be torn between “wrong” and “tragic.”».

To understand the quality inherent in the extraordinary distressing process to which Kapital's garments are subjected, it is necessary to emphasize the love for the vintage aesthetic that underlies the brand. As Oliver Leone of @yourfashionarchive told nss magazine: "The real vintage-lover values features like fading, distressing, and bleeding". A mind-set that is perfectly reflected in the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi – the beauty of what is imperfect, asymmetrical but also lived and unpretentious.

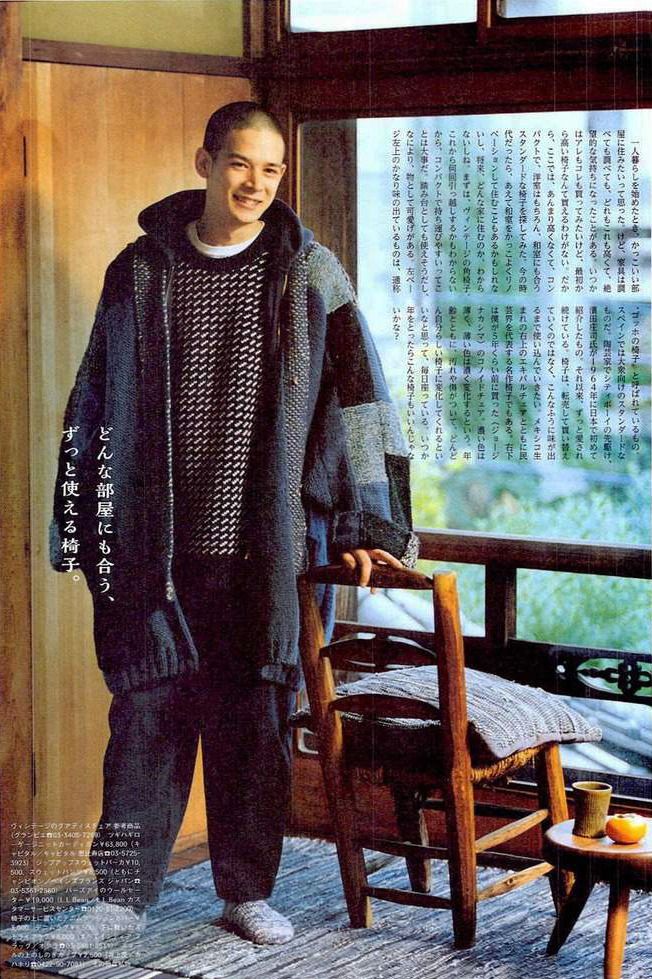

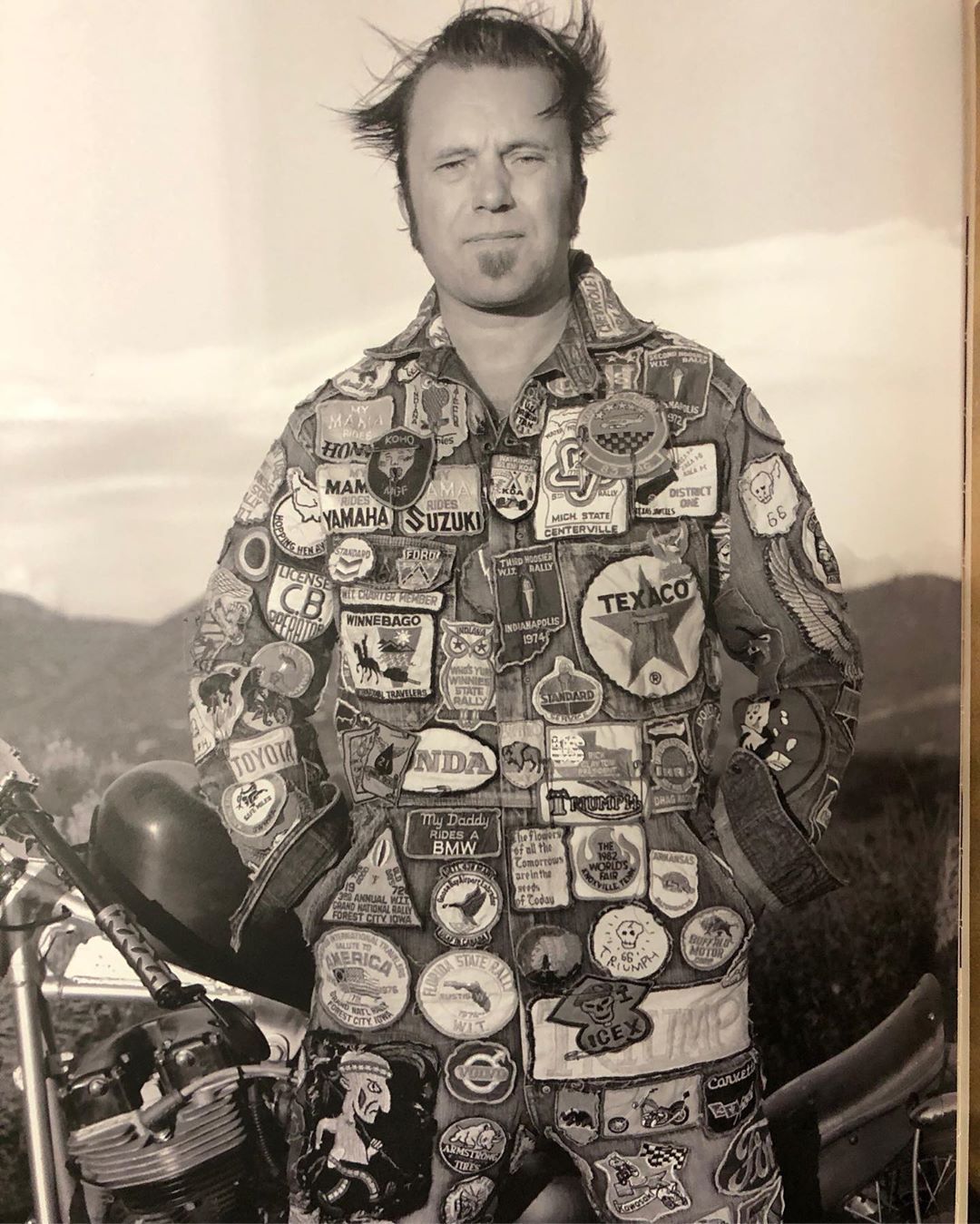

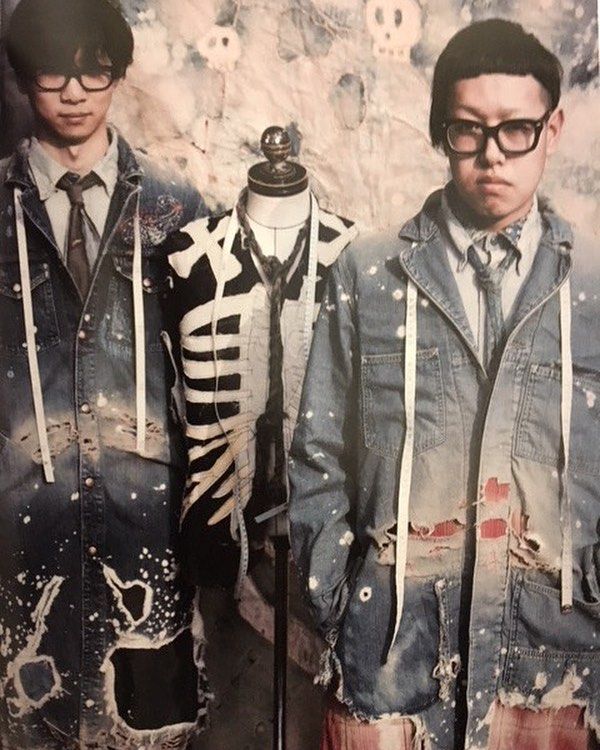

The brand was born as a product of the love of Toshikiyo Hirata, Kiro's father, for vintage American jeans and clothes – love born in the 80s, when Hirata Sr. was in the USA as a martial arts instructor. Upon his return to Japan in 1984, the former karate instructor opened Capital Ltd., the brand's current denim factory, and a vintage clothing store. Years later, Toshikiyo's son Kiro followed a similar path to his father's, going to study art in the United States and falling in love with Americana aesthetics. Upon his return Kiro worked for the 45R brand but in 2002 left him to return to the family business and, from the combination of his avant-garde sensibility with the precise artisan know-how of Hirata Sr., Kapital's current style was born.

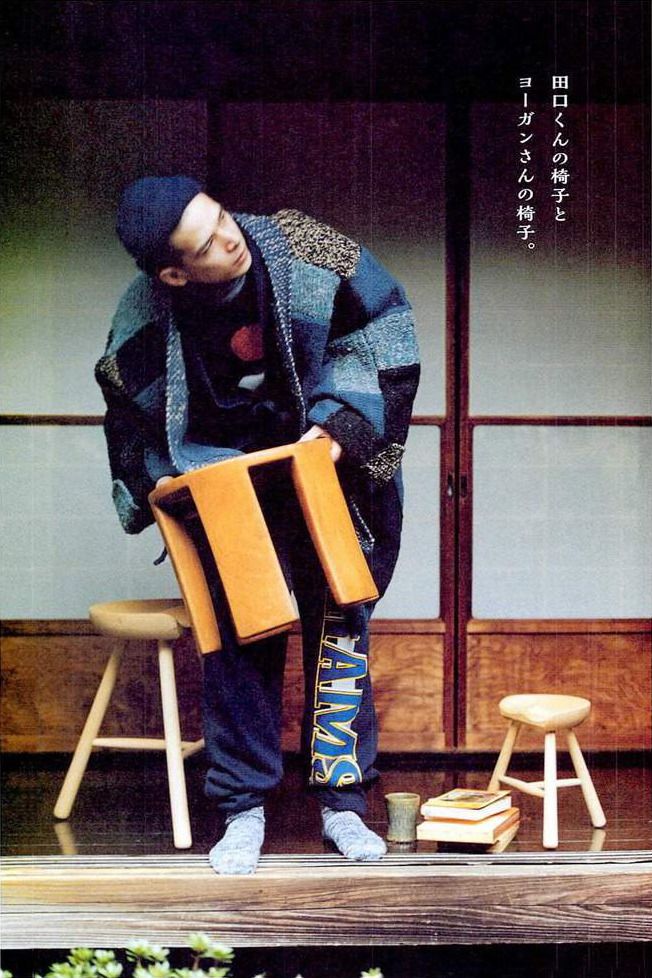

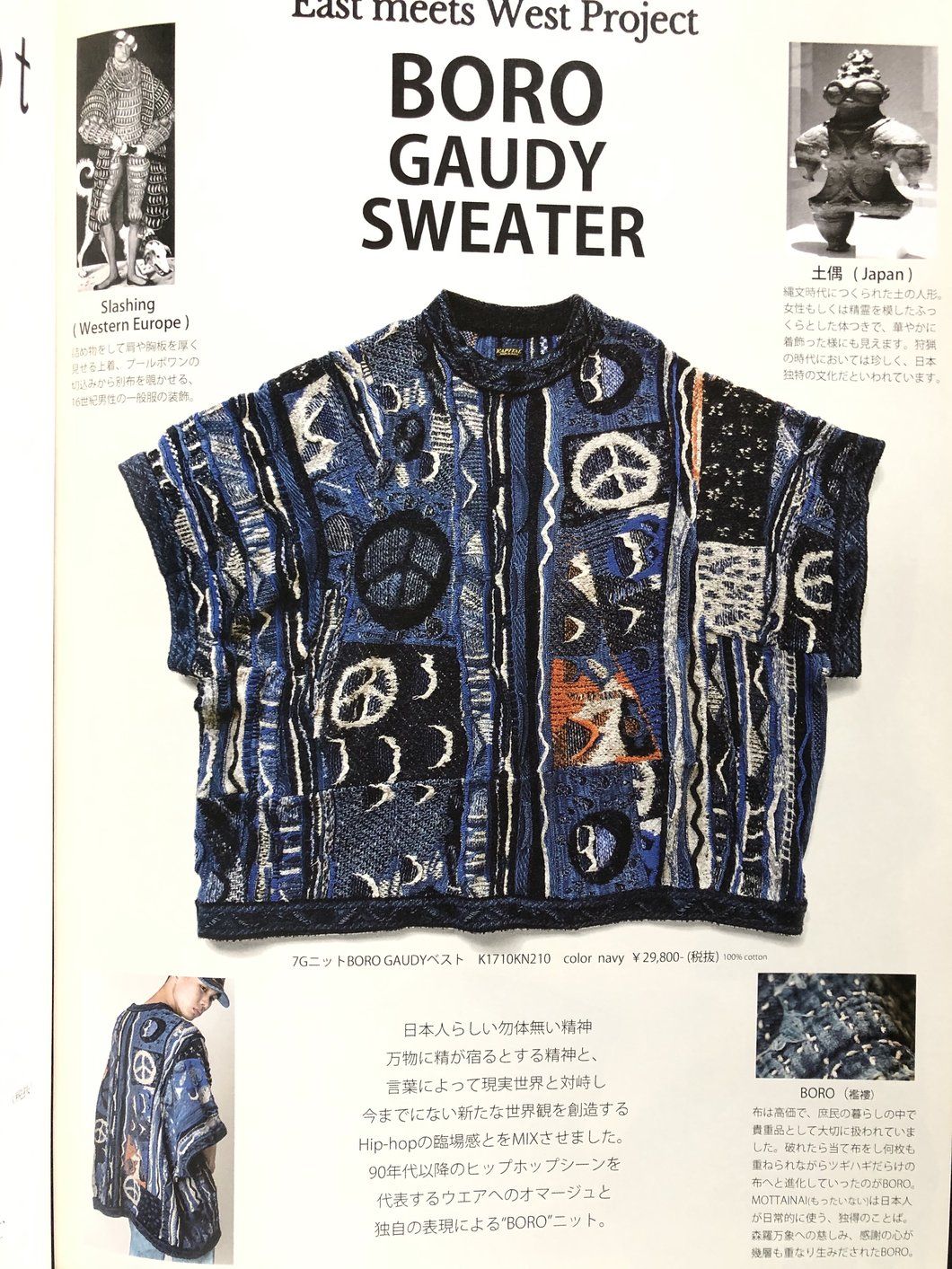

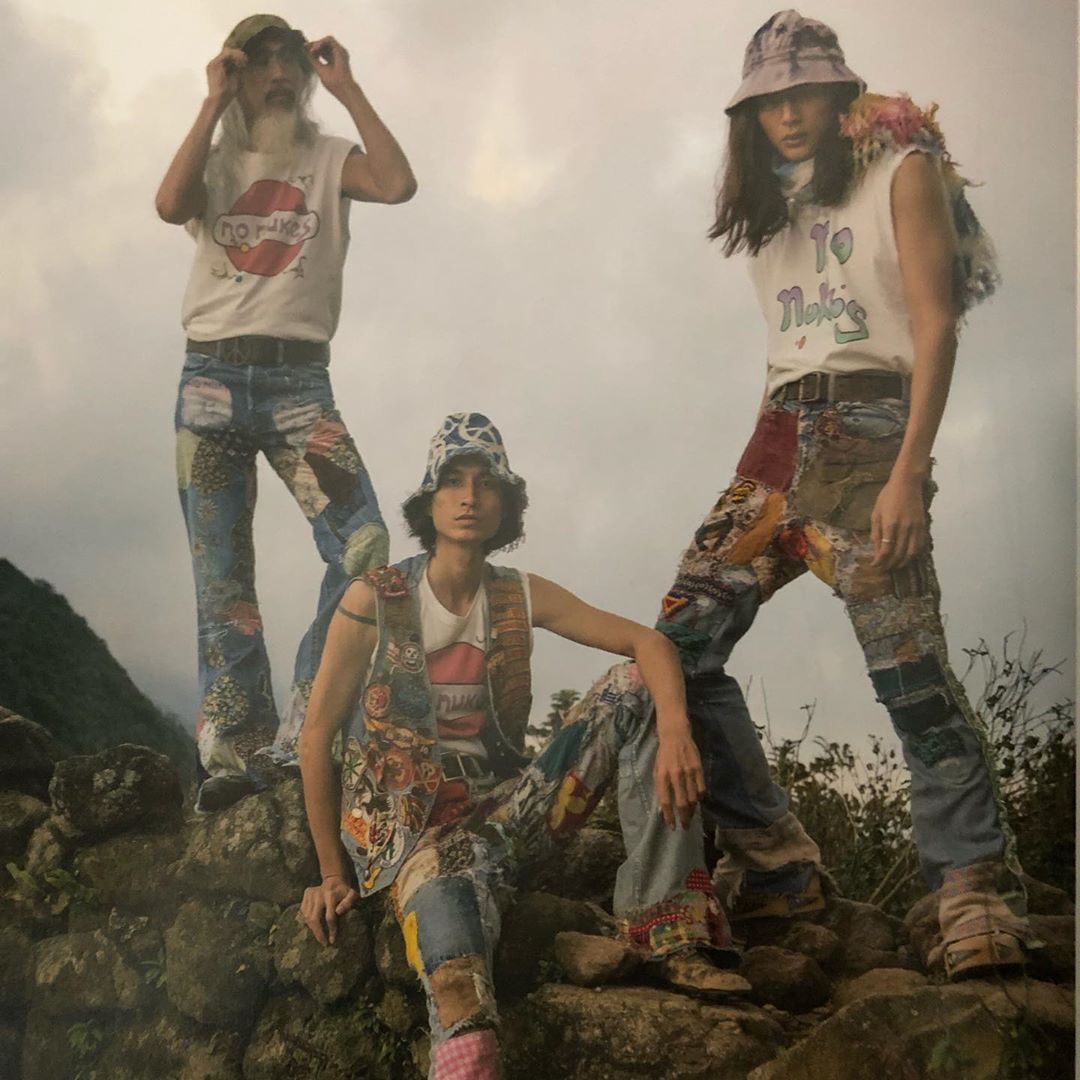

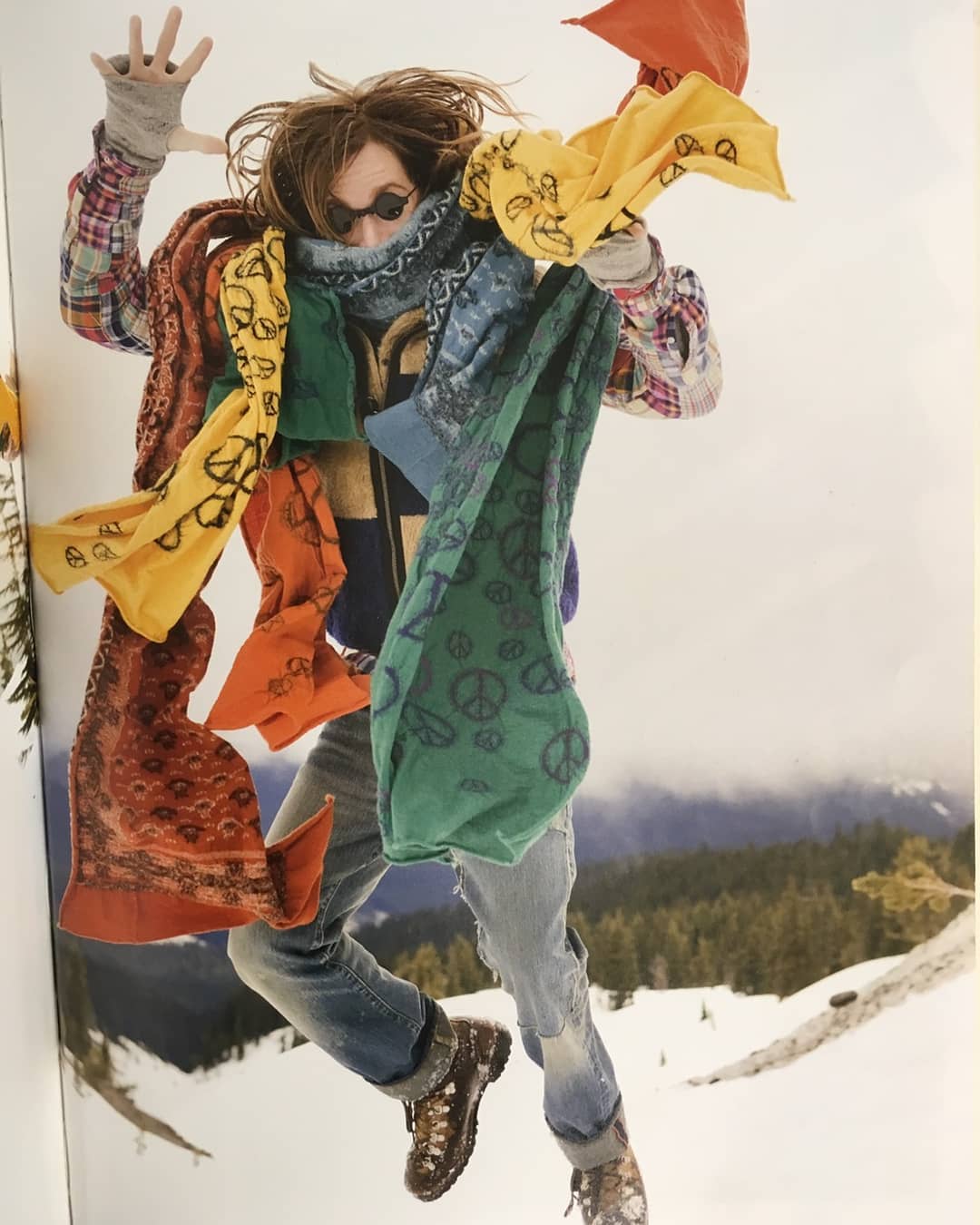

Kapital's clothes recall the hippie culture (the smiley, for example, is one of the brand's recurring symbols) but they do so in an absolutely unsterif way, exploring rather the experimentality and fringes more avant-garde of its aesthetic and making artfully ruined products, completely devoid of that patina of wholesomeness that many would expect from a globally widespread and celebrated brand. In the case of Kapital, the mixture of the youth countercultures of the 50s and 80s produces a cultural clash, as Kiro Hirata himself calls it, which is at the very center of the style of the brand. Not only that: the concept of cultural clash is a central element of all Japanese streetwear, which used to import into the East the style of subcultures separating it from the lifestyle to which it was associated in the West, creating a gap between style and culture that, creatively speaking, allowed designers like Hiroshi Fujiwara, Nigo and also the two Hirata to rework the expressive modules with a completely new freedom and giving to the type of streetwear that was realized in Japan an eclecticism it had never possessed before in the West.

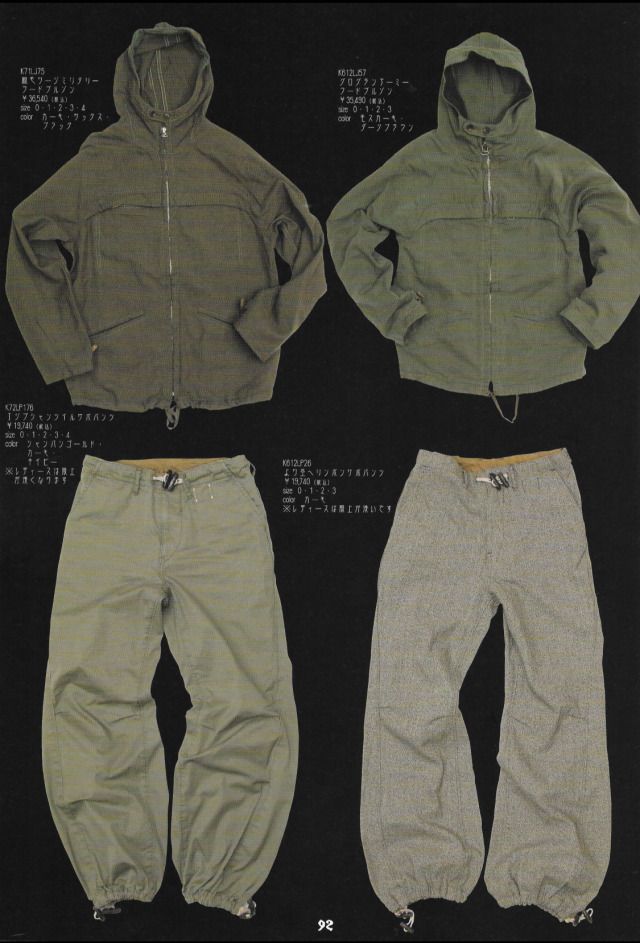

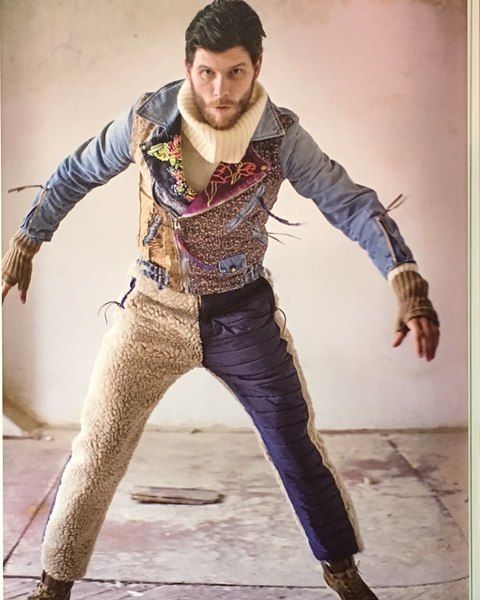

An important element of the brand's aesthetic is precisely the sheer drama of fits and silhouettes: jeans decorated with ancient sashiko sewing techniques, denim jackets with collars and bottom edges sawed off, three-dimensional-looking duvets intertwined with historical techniques of the Jomon period, treatments based on persimmon juice that make jeans stiff and almost sculptural in their fit, flannel shirts created stitching together five different shirts, the use of the traditional Japanese Boro technique that involves the overlapping of different fabrics held together by a decorative seam pattern, creating that DIY patchwork aesthetic that makes the items seem antique – every single piece has unique details and intentional flaws that, ideally, should accumulate more and more welcoming, so to speak, in the design of the garment the very life of the wearer and making it unique in its kind. According to this conception, which always falls within the scope of the wabi-sabi philosophy, the garment must not remain intact and unchanged from the moment of sale but, on the contrary, enrich itself with details with every wear and tear or stretch marks – details that in the factory would not be possible to recreate and that ultimately constitute the sense of experience that makes each piece special.

Kapital's clothes are more valuable for the spirit with which they are created than for the opulence of materials or the sartorial acrobatics of design - which are not lacking. Wearing them is an experience and the experiences you make wearing them end up affecting their own final appearance – in a word, the clothes change along with the wearer, transcending the same concept of simple jeans and becoming almost living creatures, in a constant stream of subtle transformations.