The history of the most iconic color of luxury How the orange nuance was chosen as the symbol of Hermès

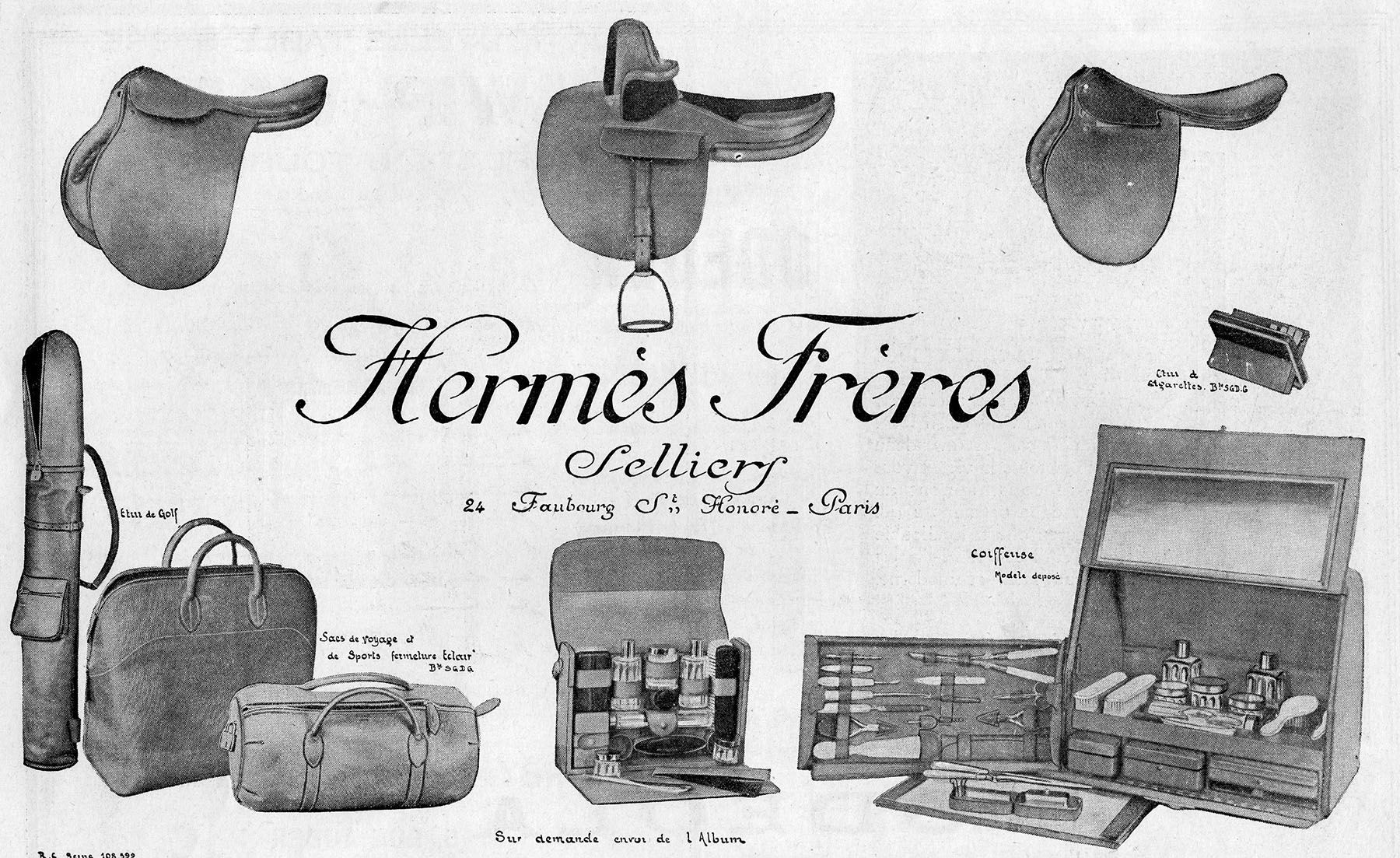

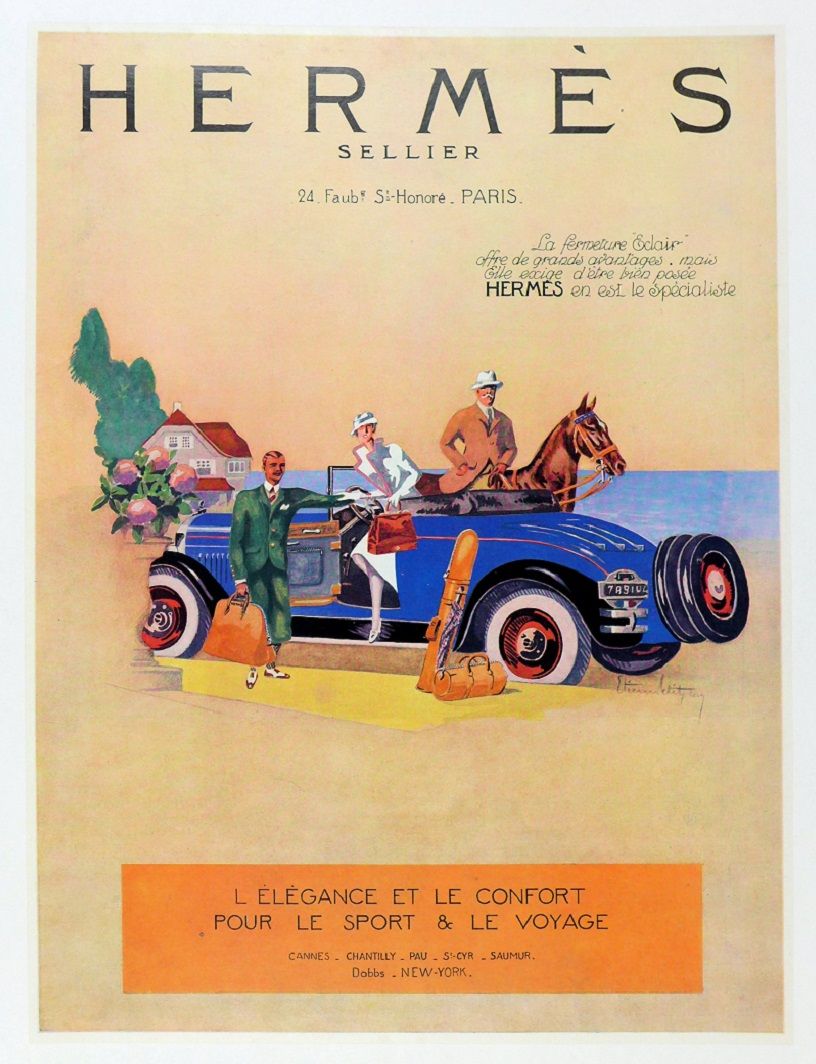

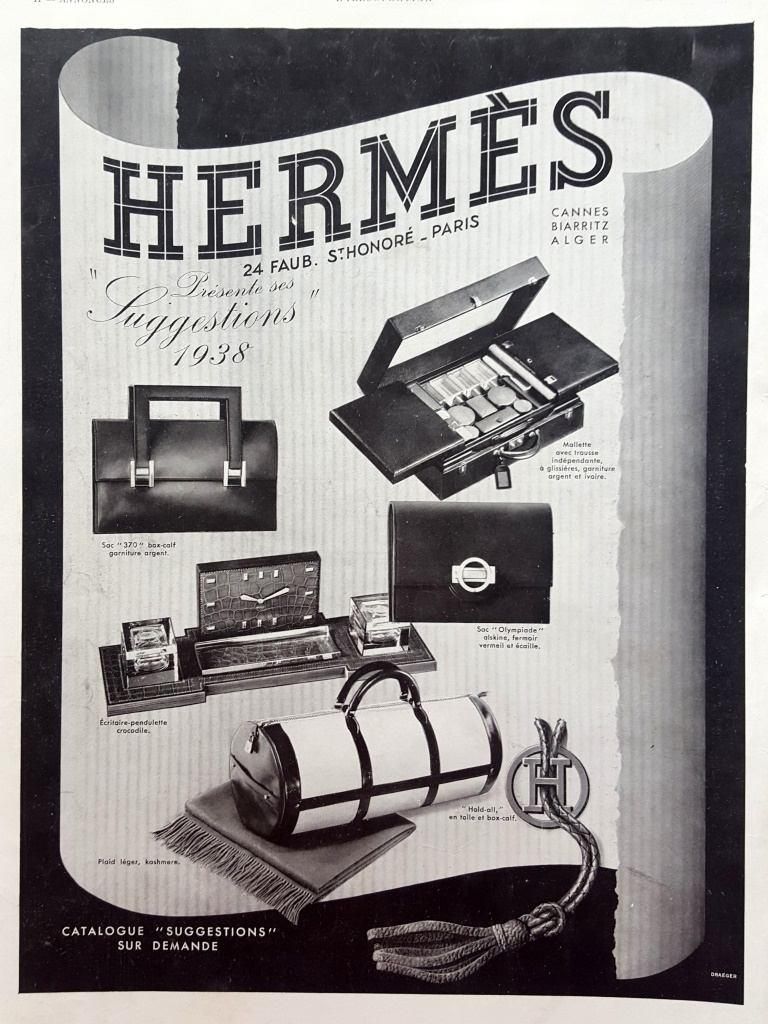

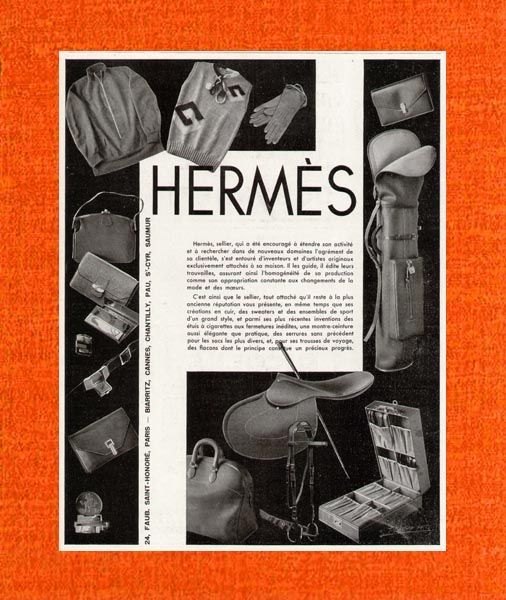

Few packagings in the history of fashion are immediately recognizable as that of Hermès. At 183 years old, the Parisian brand has such a strong identity that it does not need expensive marketing strategies or advertising campaigns that can be summed up in the words of its previous CEO Jean-Louis Dumas: "We don't have a policy of image, we have a policy of product".

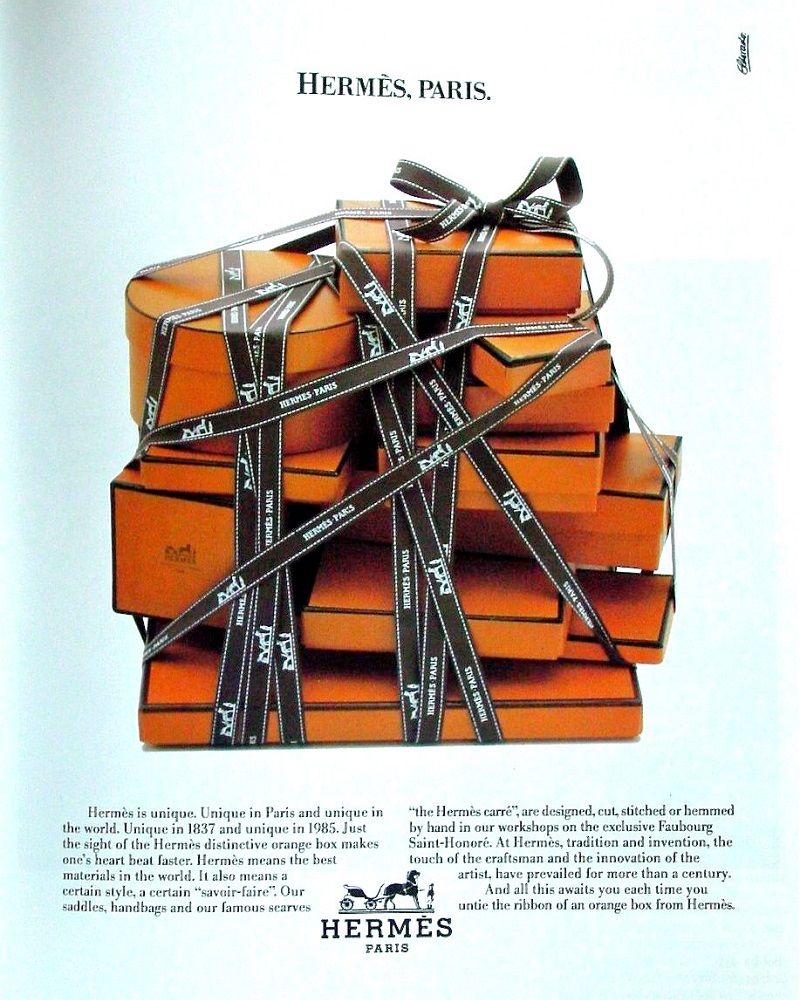

And the packaging of Hermès products – an iconic orange box – is the first through the aura of quality and sophistication associated with the Maison. That box, however, did not always have that colour: originally the packs of Hermès were cream colour. The history of their evolution is linked to the history of Paris and Europe.

In 1942, World War II had been underway for three years and Paris was occupied by the Nazis for two years. The conditions of the city and its inhabitants were disastrous, not least because the war had hampered trade and transport and even food was rationed: milk was available only for the rich and an average family received a little more than a hundred grams of sugar and about eighty-five grams of meat, including bones, each week. Even the Hermès boutique, which had been open for 105 years and operated by Emile-Maurice Hermès, had run out of packaging stock and there was no one who could get them. His usual supplier had boxes of the colour that no one wanted: orange. Emile-Maurice added a brown ribbon and a horse-drawn eye logo to the box. That's how Hermès' packaging was born.

Hermès' orange varied over time, stabilizing after the 1960s to what we know now. The constant use that the brand makes of colour has made the latter a real indicator of origin – although the legal status of the shade, which is not part of the Pantone colours and is therefore not categorized precisely, is interesting. Hermès has in fact registered trademarks for its colour all over the world but in 2005 the European Union Intellectual Property Office refused to register the colour as a trademark because, according to the judges, orange is too common a colour to be associated with a single brand, which lacks distinctiveness, adding that consumers do not identify a brand by colour only and that, taken in itself, registering a colour would mean granting an unjustified monopoly. Over the years, appeals were filed, but they were rejected. At the moment, the legal battle is not over.