The ultimate guide to Russian fashion Waiting for the Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week Russia

Not just London, Milan, Paris and New York. From 13 to 17 October, it is up to Moscow to dictate the style for the next SS19. Founded in 2000 by Alexander Shumsky, Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week Russia has grown more and more, moving from 18 designers of the first edition to over 170 in 2018. Although the Soviet fashion scene is relatively young, born when the USSR collapsed in December 1991 and developed a decade later, in the last period is gaining international attention, thanks to stars like Demna Gvasalia and Gosha Rubchinskiy. Russia is now one of the largest retail markets and one of the most dynamic European economies, to the extent that the German state agency Trade & Invest (GTAI) estimates that it grew 5% to 2.4 trillion Russian rubles in 2017 (€ 34.1 billion). What are the prospects for the industry? According to Shumsky:

"The reality of fashion has changed [...] It's time to focus on thousands of talents that could become strong niche brands like a collective unicorn."

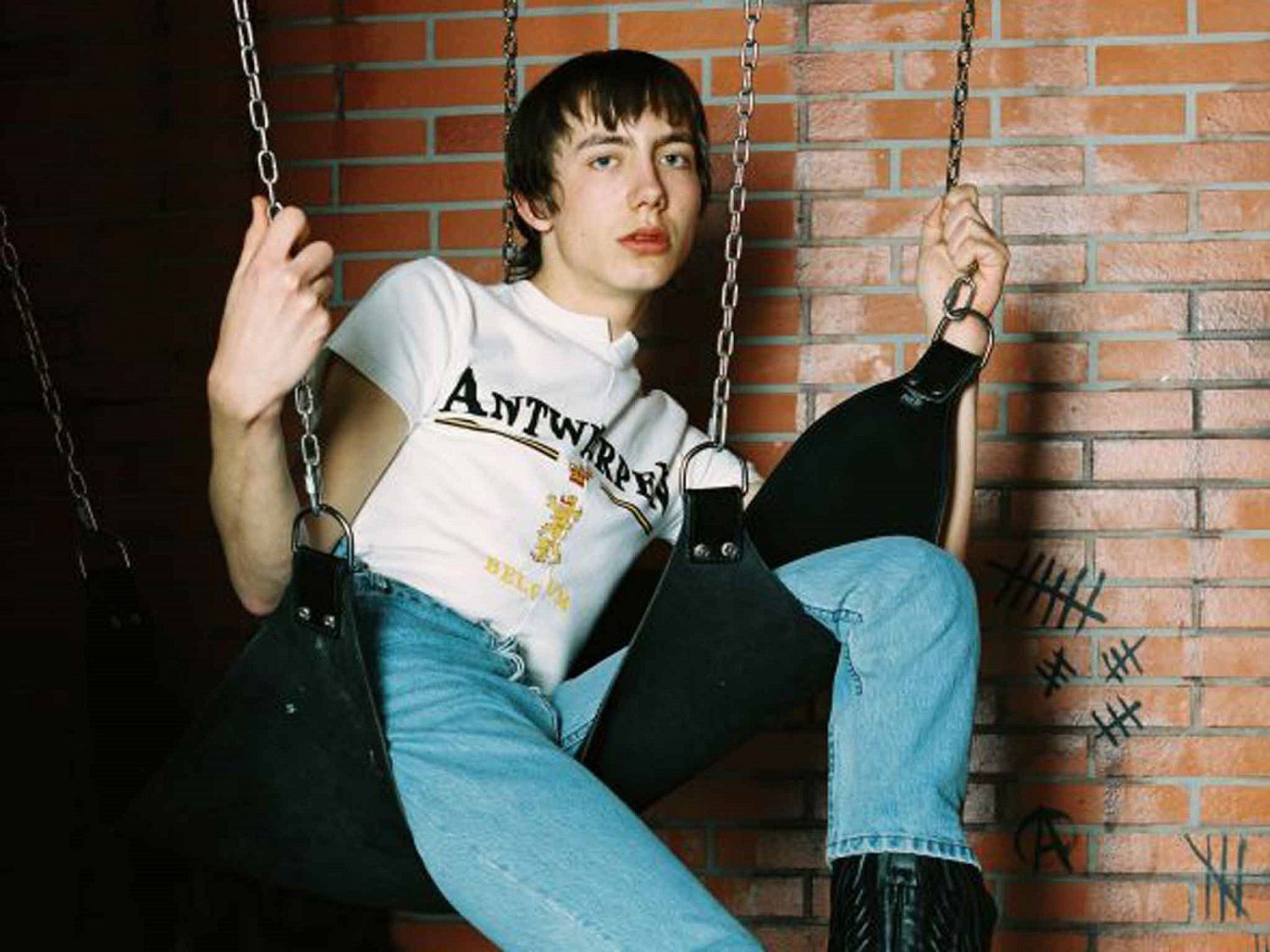

The designers on which to bet for the future are newcomers who "reject the classic dogmas preferring a celebration of almost chaotic fashion, from raver, closer to the everyday life of teenagers", those who not only conquer the millenials, but who manage to create hype, helping the underground world to become mainstream. While the countdown for the FW continues, nss explains what you need to know about fashion made in Russia.

History

Furs, sables covered with gold laminae and studded with stones, precious fancy silks, richly decorated fabrics. The beginning of the history of fashion in Russia coincides with the opulence of the courts of the tsars, figures linked to an imperishable image symbol of greatness. They are absolute monarchs, able to dictate the law and to shape the aesthetics of an entire nation, regulating even who can wear what. With Peter I, for example, a great lover of European art, the country suffers a profound westernization. Among the many reforms implemented, stands out the prohibition of traditional Russian clothes and the introduction for women of corset and fontage, an elaborate French hairstyle with curls, ribbons, lace, supported by a metal armor. During the reign of Catherine the Great, a German by birth, instead, at court, the nationalist character is emphasized again, and in the wardrobe cohabitant wreaths and wigs coexist with French versions of traditional Russian garments (kaftans, sarafans and kokosniki).

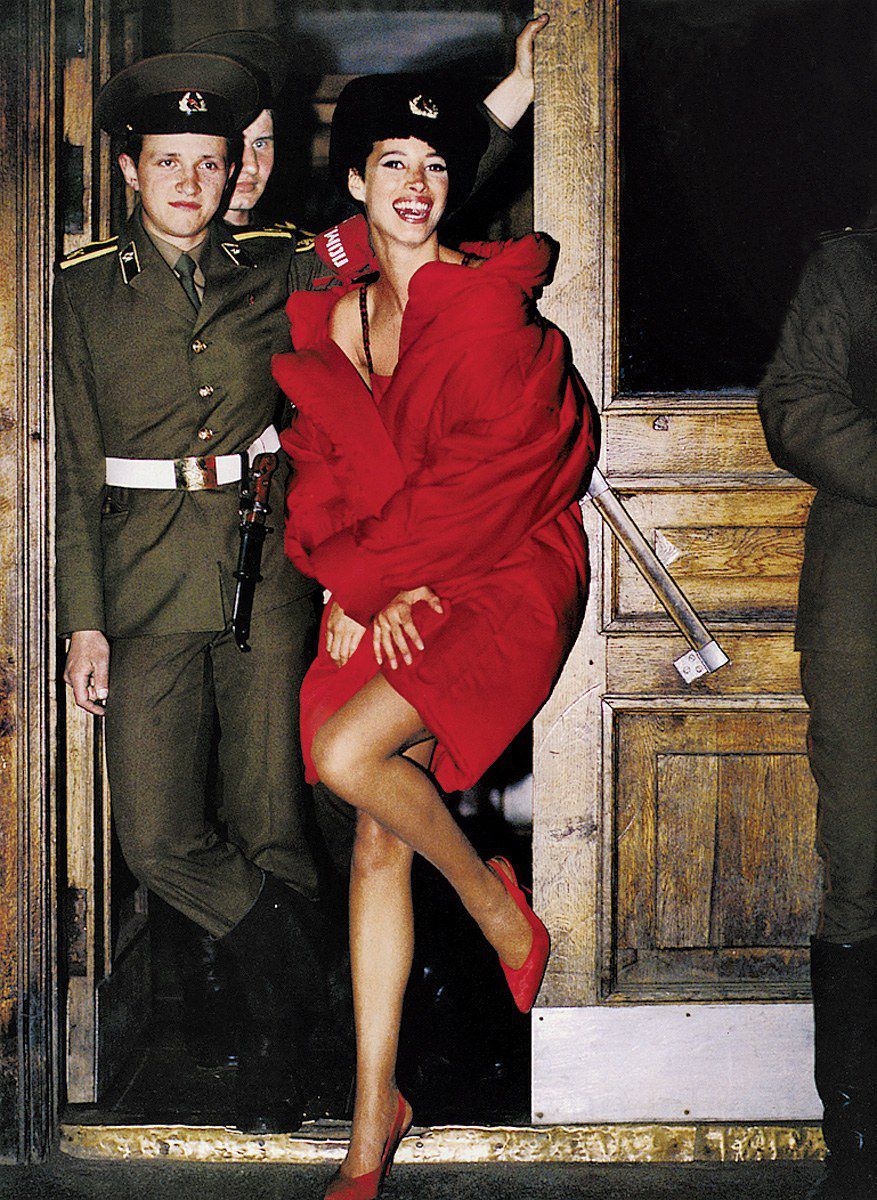

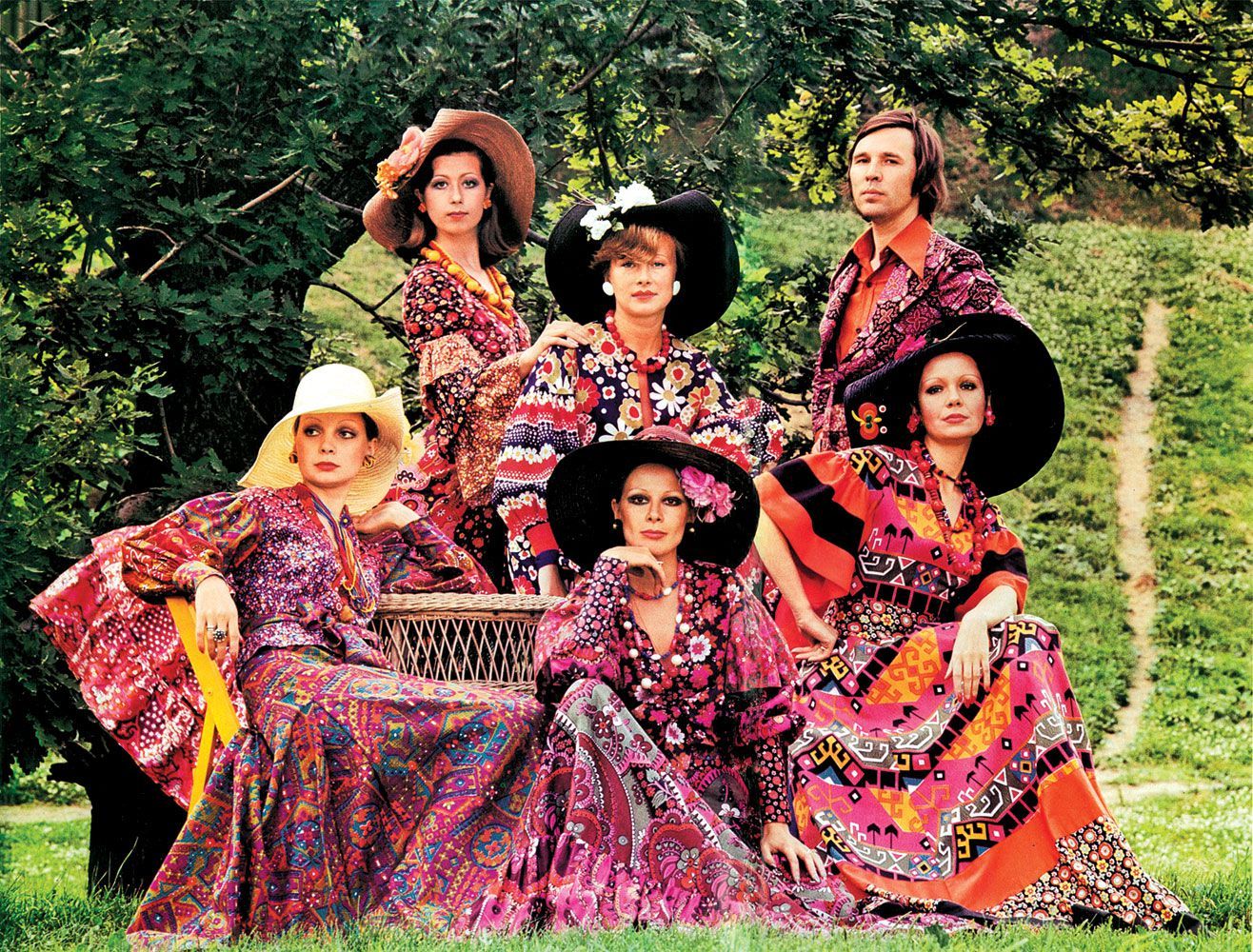

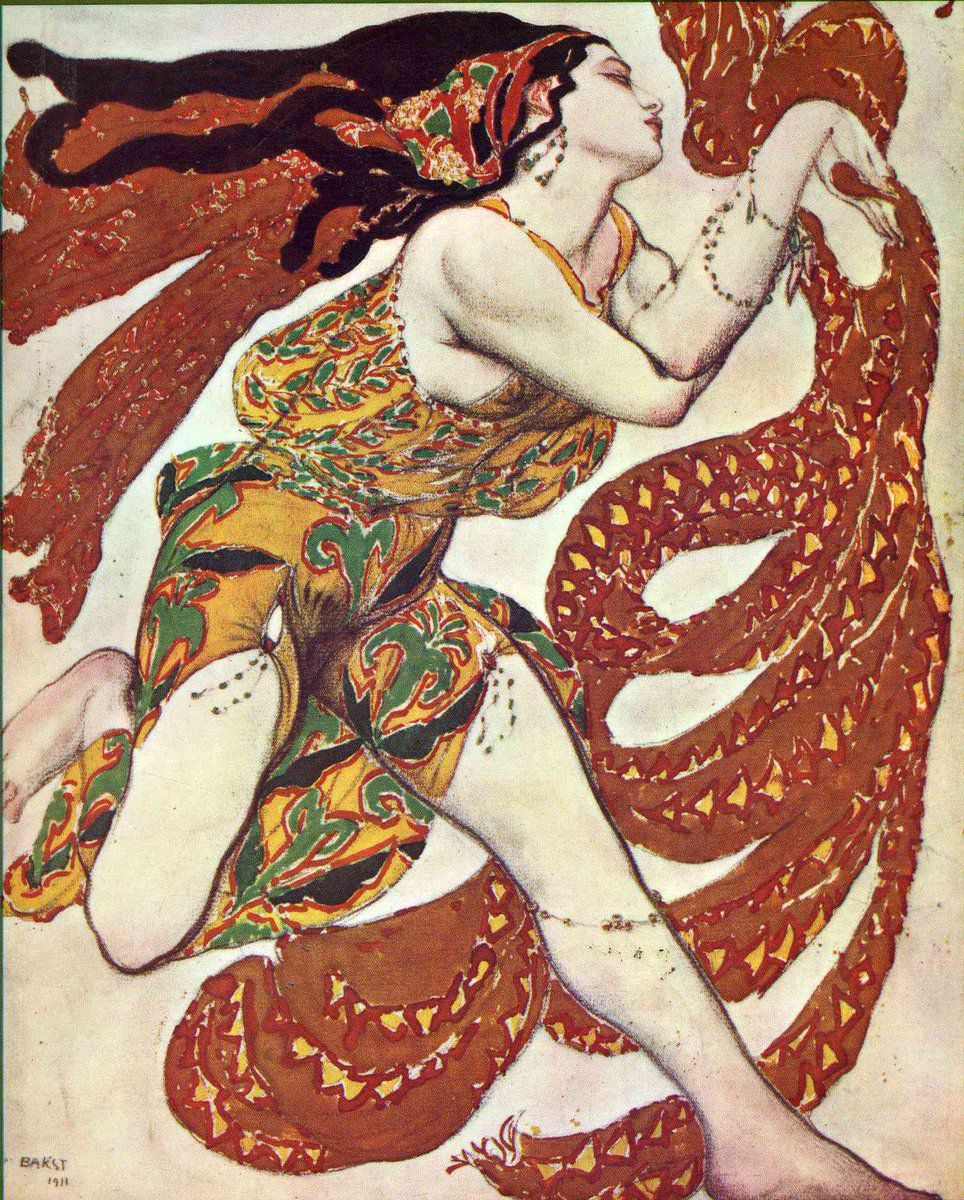

If during the Belle Époque period, from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th, the ideal of woman-flower, ethereal and fragile, with "hourglass" shapes, in the pre-war years the clothes began to appear more showy, exotic and thanks to the Russian Ballets and the costumes created by Lev Bakst, Russia dictates the style in Europe, imposing the brilliant contrasts of color in the classic folk embroidery, the bias buttoning, the sarafan, a traditional dress consisting of tunics worn over the trousers. Bakst's drawings have a huge influence on many designers. Recognizable almost 50 years later, in the "Russian Collection" by Yves Saint Laurent of the late '70s, she particularly feels about Paul Poiret playing with the "silhouette lampshade", primary colors, harem pants, wraparound skirts and Oriental inspiration, Cossack style coats finished in fur and folkloric embroidery.The arrival of the war coincides with a return to simplicity and the clothes begin to look more and more like the military uniforms, the skirts get shorter, the women get rid of the busts and they begin to keep their hair short.

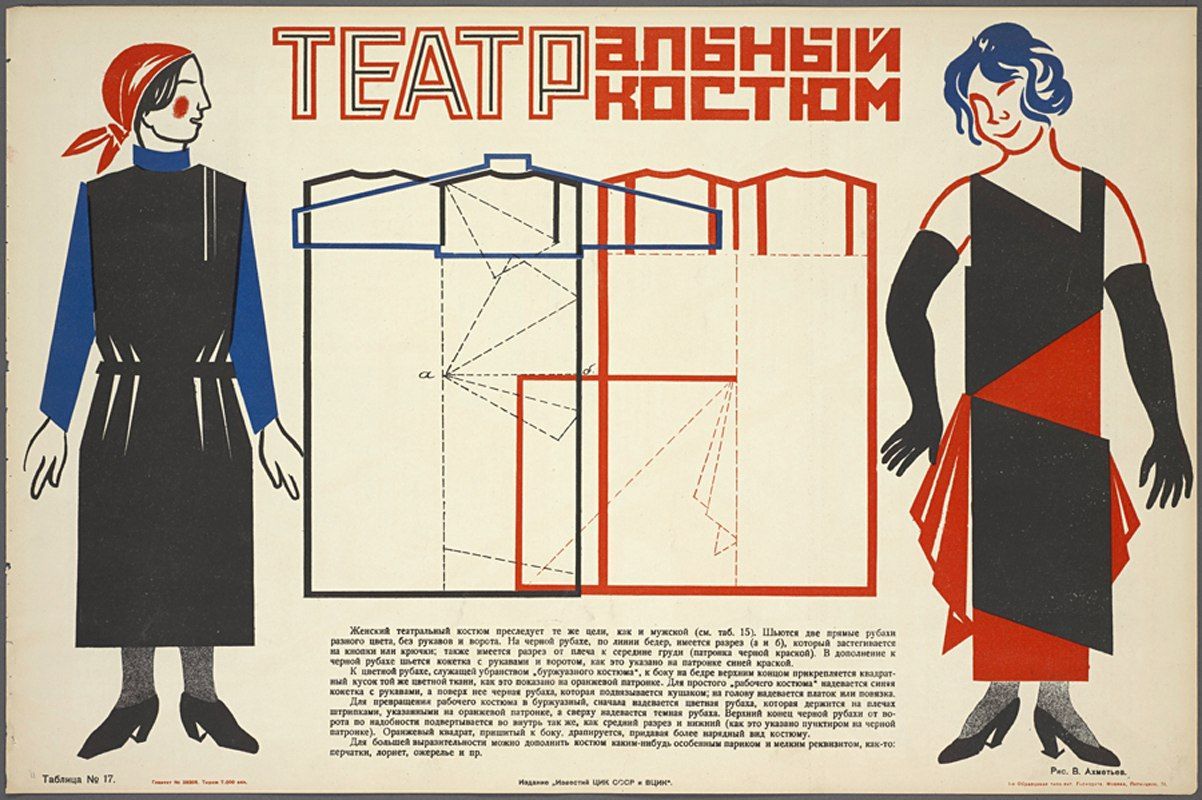

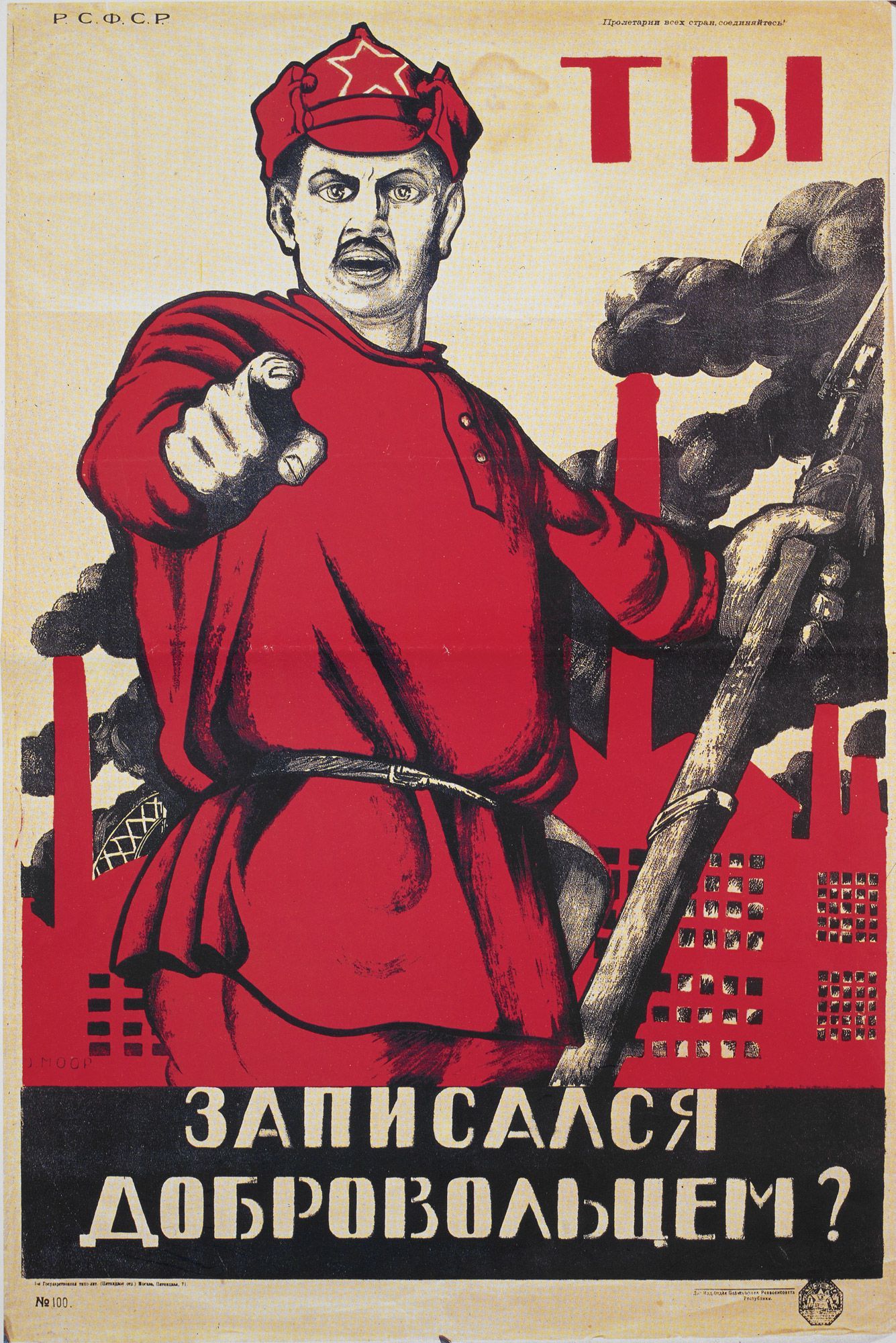

With the October Revolution, for ideological reasons and scarcity of resources, civil fashion undergoes great transformations: women show off the red handkerchief tied at the nape as a symbol of women's emancipation, boys and girls of the Komsomol wear the "jungshturmovka", a uniform (green jackets with collar, patch pockets and leather belts) borrowed from the young co German munists belonging to the organization of the "Red Jungsturm". At the same time, Lenin founded a state-run design and modeling school in Moscow, and the first Russian women's fashion designer, Nadezhda Lamanova, created a collection presented during the 1925 World Expo in Paris. La Nep (New economic policy) brings a certain abundance and from Europe filter the trends of the "Roaring Years". The Stalinist style combines motifs of the Soviet tradition with contemporary Hollywood glamour and the progressive militarization of the country translates into the introduction of uniform even in the civil professions. From the years of the thaw until 1991 there is the tendency to idolize the western products that make the black market flourish and the imitation of European or American goods. If the first fashion atelier was inaugurated in April 1944, in the Mertens house, at number 21 of Nevskij Prospekt, designer Slava Zajtsev founded the first Western-style fashion house, which, dubbed the "Red Dior", in the late 80s is the protagonist of the catwalks of the whole world.

The importance of Gosha Rubchinskiy and Demna Gvasalia

Call it "post-soviet style", "post-soviet cool" or as you like, the result does not change: almost thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, in the former USSR, fashion is resurrecting and is being imposed with strength on the international scene. To dictate the new aesthetic are Gosha Rubchinskiy (for many so important to compare its influence on the world industry to that of the Ballets Russes of Sergei Diaghilev), Demna Gvasalia and Lotta Volkova. Their fashion philosophy feeds on contaminations between sportswear, digital culture, vintage, skate, hip hop, heavy metal, '90s streetwear, youth subculture and Soviet history, giving life to an aesthetic often at the limit of the ugly, underground, hyper-realistic, raw, which draws heavily on the road. As stated by Alexandre Samson, one of the curators of the Parisian fashion museum Palais Galliera, "it is a nostalgia of the past without nostalgia", an aesthetic typical of the Slavic culture, similar to the Berlin underground style. The turbulent years that followed the collapse of communism become oversized sweatshirts, deconstructed logo, bomber, suits similar to adidas, jackets with dilated and squared proportions, long trenches, garments with Cyrillic lettering and communist symbols. These new "gopnik" with their DIY ethics, ninth only pushed many emerging creative designers, streetwear brands such as Sputnik1985 or Volchok, to pursue the international spotlight, but also have a spotlight on other designers.The Russian scene is diverse, prosperous and inside are distinguished names like Vika Gazinskaya, avant-garde pioneers like Nina Donis, emerging talents like Tigran Avetisyan and Yulia Yefimtchuk, but also the haute couture with the strange peasants and princesses of it girl Ulyana Sergeenko.

Trend made in Russia

Always insulated from a protectionist policy, the interest in Russian culture and Russian dress is oscillating. The first attempts to infiltrate foreign territory date back to 1400, when the sable, fox, wolf furs and "Turkish" styles began to be used by the Italian merchant class, as evidenced by some works by Tiziano and Tintoretto. Even the reformist tsar Peter the Great inflames the spirits of Europeans, as after 1814 the Cossacks and Hussar regiments of the army, but it is Djagilev's ballets that impose the Russian theme in 20th century Europe. The echo of their impact crosses the epochs, by the famous French designer Paul Poiret, who introduces the Ukrainian embroidery and the Cossack boots into Parisian fashion, passing through the second half of the 20th century with the "Russian Collection" by Yves Saint Laurent and coming to the 2000s when they began to come out one after the other: "Paris-Moscow" by Lagerfeld for Chanel, the "Russian line" by Marras for Kenzo, the proposals in the spirit "à la russe" by John Galliano, Roberto Cavalli, Valentino and Dolce & Gabbana. So many are the garments from the homeland of Gogol and Dostoevskij that become popular trends in the world: the "boeroro collar", the Slavic ornaments, the beautiful "kokoshnik of the North", the shawls with tassels, the floral dresses, the embroidered shirts, the colbacchi, the lavish skirts with the underlined waist and the castigated collars, the massive necklaces and earrings, the long coats to the Cossack, but also essential pieces in the last months. Some examples? As the Russia Beyond website suggests: the net bag inspired by avoska, a string bag that was used to go shopping in the 70s; the workwear worn as casual wear; the wide-shoulder jackets and oversized tailoring so beloved by Balenciaga, Vetements, Calvin Klein and Martine Rose; the "Proshchaj, molodost", low boots with a felt padding and a thick rubber sole, also reproposed The North Face; galoshes; the crest cap of the rooster; sandals with socks.

Fashion vs Politics

Vodka, ballet, literature and now also fashion. Thanks to the millennials, which have become the most influential demographic segment of this sector, Russia dominates in terms of style. Before, however, of the recent success of Rubchinskiy & Co., the country has spent most of the twentieth century dressed in uniforms pre-approved by the state. From the tsar to Stalin's regime, fashion and power went hand in hand and every change in one coincided with one revolution of the other. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the people finally have the opportunity to choose and experiment with the wardrobe. Despite this, until recently, Russia has struggled to produce a globally recognizable fashion brand or a commercially viable trend. Gvasalia and other contemporary Italian designers have a miracle that the current government wants to try not only to replicate, but also to consolidate. This is why initiatives such as FashionNet have arisen with the ambitious goal of obtaining 70% coverage of the domestic clothing market by 2035.

Moscow Fashion Week

From 13 to 17 October Moscow will host the Russian fashion week, during which around 175 national and foreign designers will show their new collections of clothes and accessories. From Goga Nikabadze to Bella Potemkina, from Vyacheslav Zaitsev to Yulia Dalakyan, the creatives will share, as the founder of MBFW Russia, among those who focus on classicism and tradition of Russian costume and new talents who reject the classic dogmas, preferring a celebration almost chaotic fashion, from raver, closer to the everyday life of teenagers. It is probably the latter group that, more daring and future-oriented, will bring the former USSR to the center of attention. The Accelerator Fashion Futurum is also focusing on new talents and has launched a competition to allow novice designers to access the FW and a prestigious educational program.