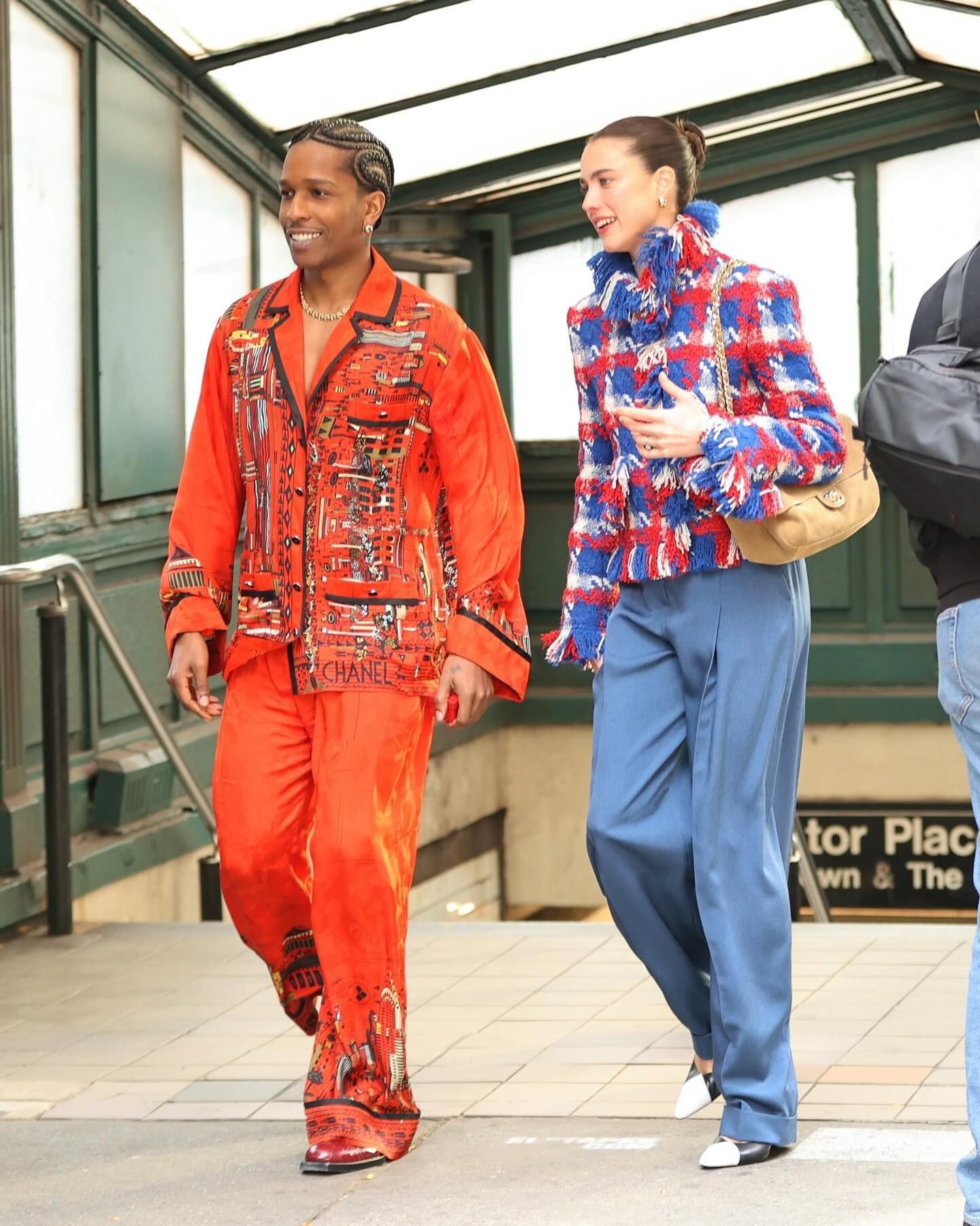

Are politically motivated t-shirts making a comeback? “Political” is the new “edgy”

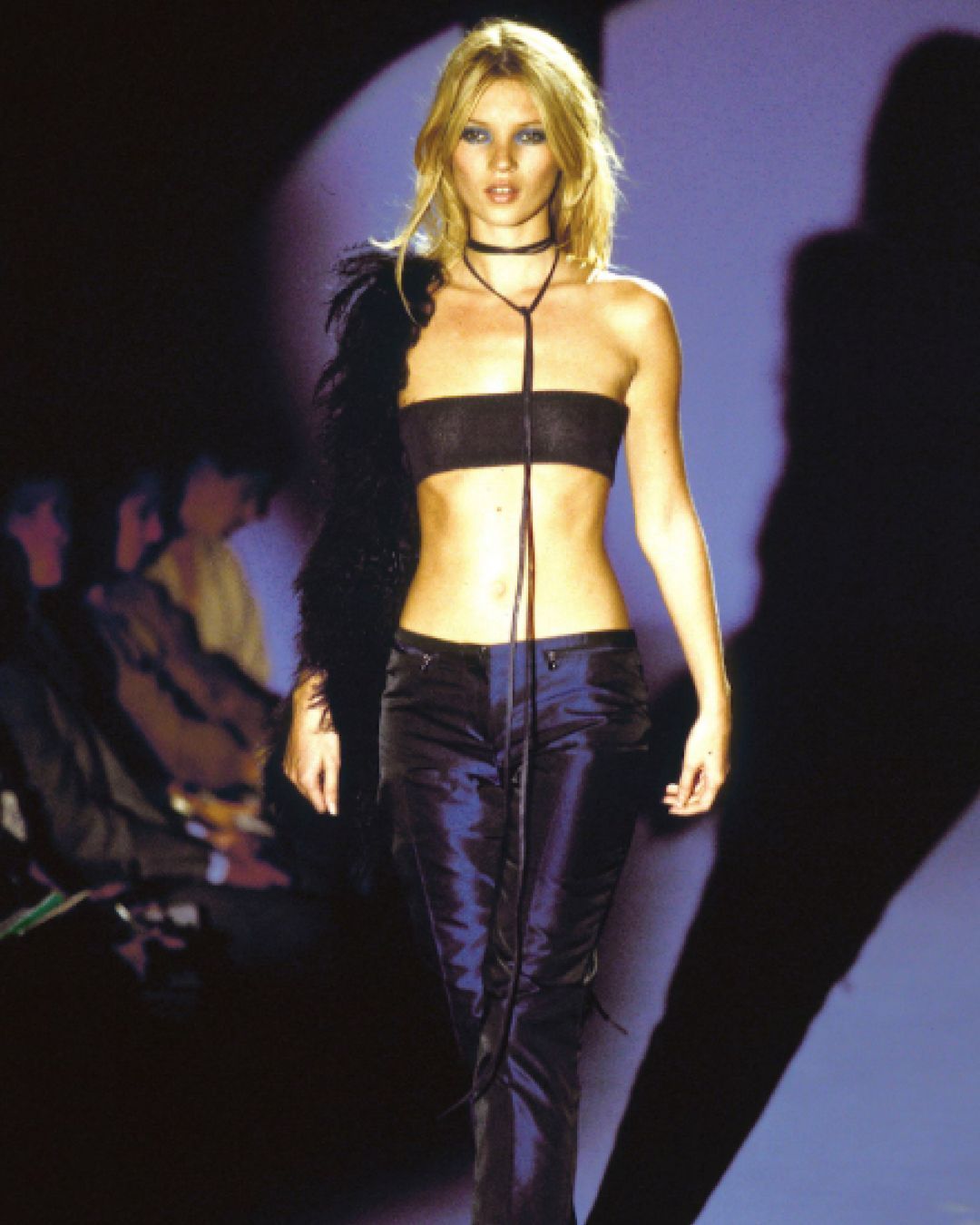

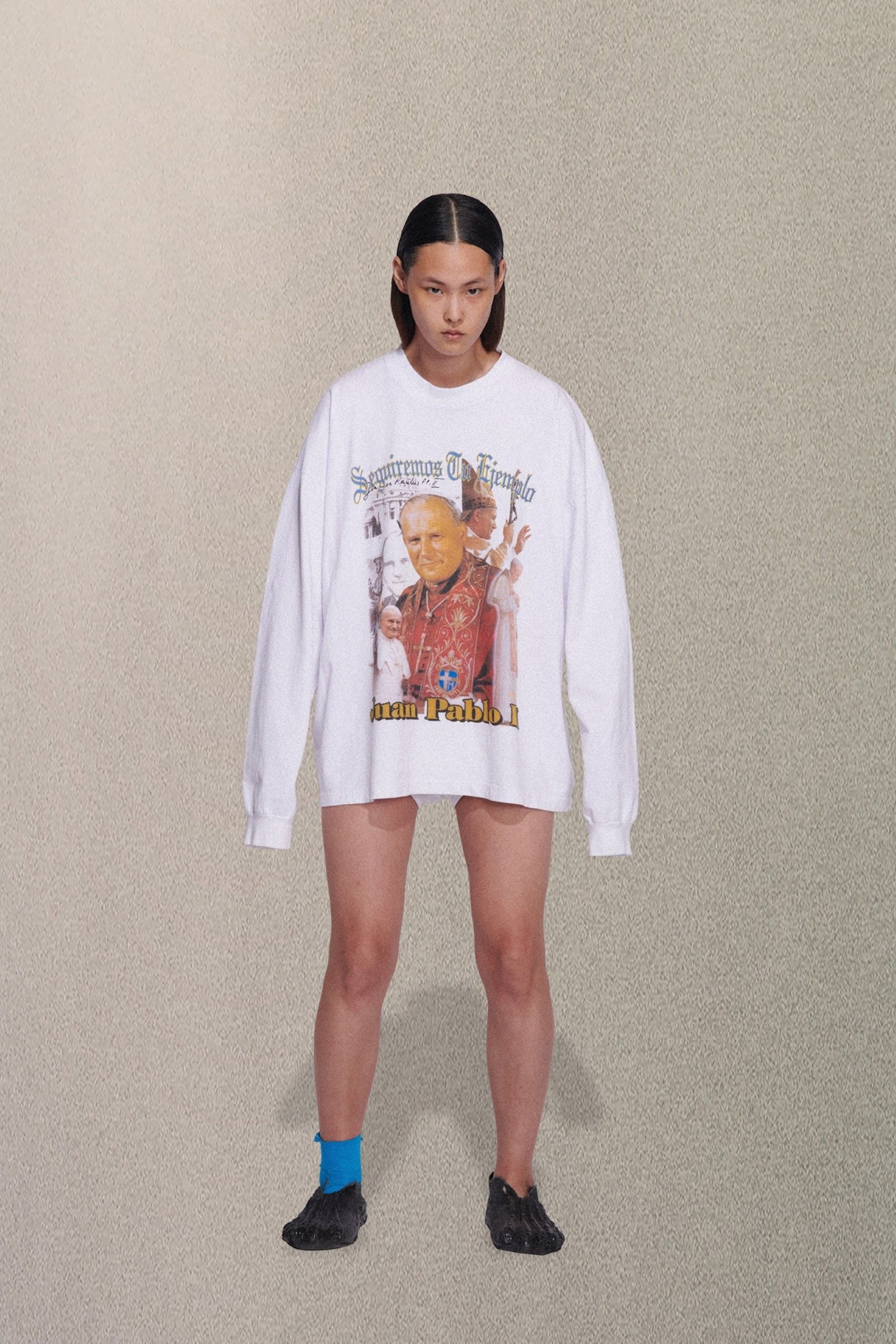

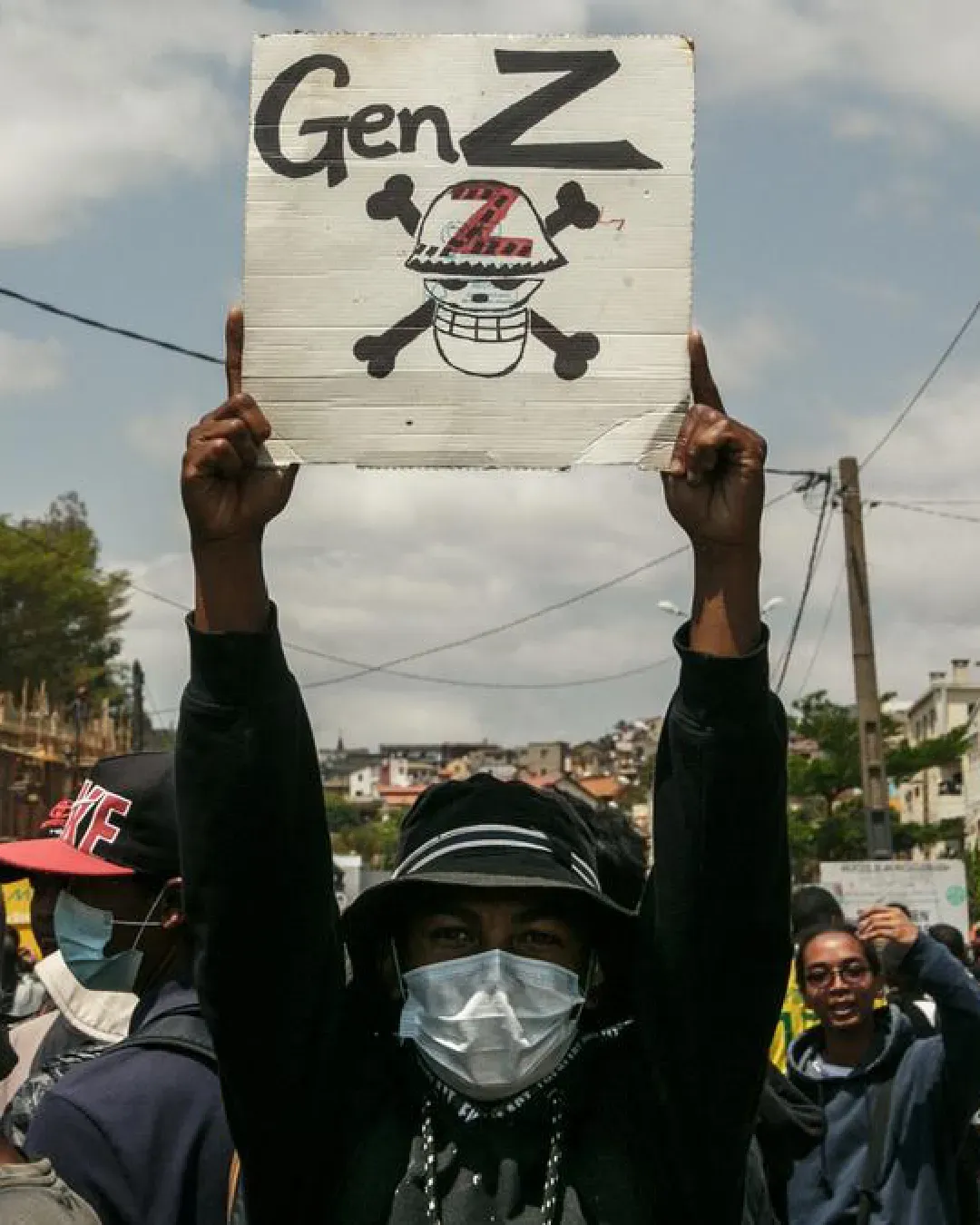

The just-concluded Paris Fashion Week unfolded with the usual energy and the usual highs and lows, but without one or another show piercing the surface of the fashion bubble-with the obvious exception of Kanye West, who with a T-shirt that read the infamous motto "White Lives Matter" threw half the fashion industry into disarray. Regardless of how inappropriate and offensive Kanye's statement was, it must certainly be noted how, on the level of social phenomenology, in an entire fashion month filled with more or less naked bodies, BDSM details, and ever-changing visions of fashion, the power to divide and upset and, in essence, to be edgy is held by a deliberately provocative political slogan printed in lettering usually associated with memes and thus lacking the slightest originality. To increase the level of randomness of his own symbolism, then, Kanye printed this slogan to a t-shirt commemorating John Paul II - the public figure one might least have expected to see on Kanye. The story does not end there because the day after the Yeezy show, while the fashion press and celebrities in the Kardashian clan thundered on social media, Kanye went backstage at the Enfants Riches Deprimès show and enthusiastically photographed the Mao Zedong t-shirts that Henry Alexander Levy made the centerpiece of his own collection. Two political icons in two days, in short, linked by a search for edginess that for both creative directors is something systemic and personal but above all for which wearing the image of a character does not follow an adherence to its ideals but becomes at once pop, sensationalist, and shocking citation. Thus the question arises: has wearing political icons and statements on one's T-shirt become the new counterculture?

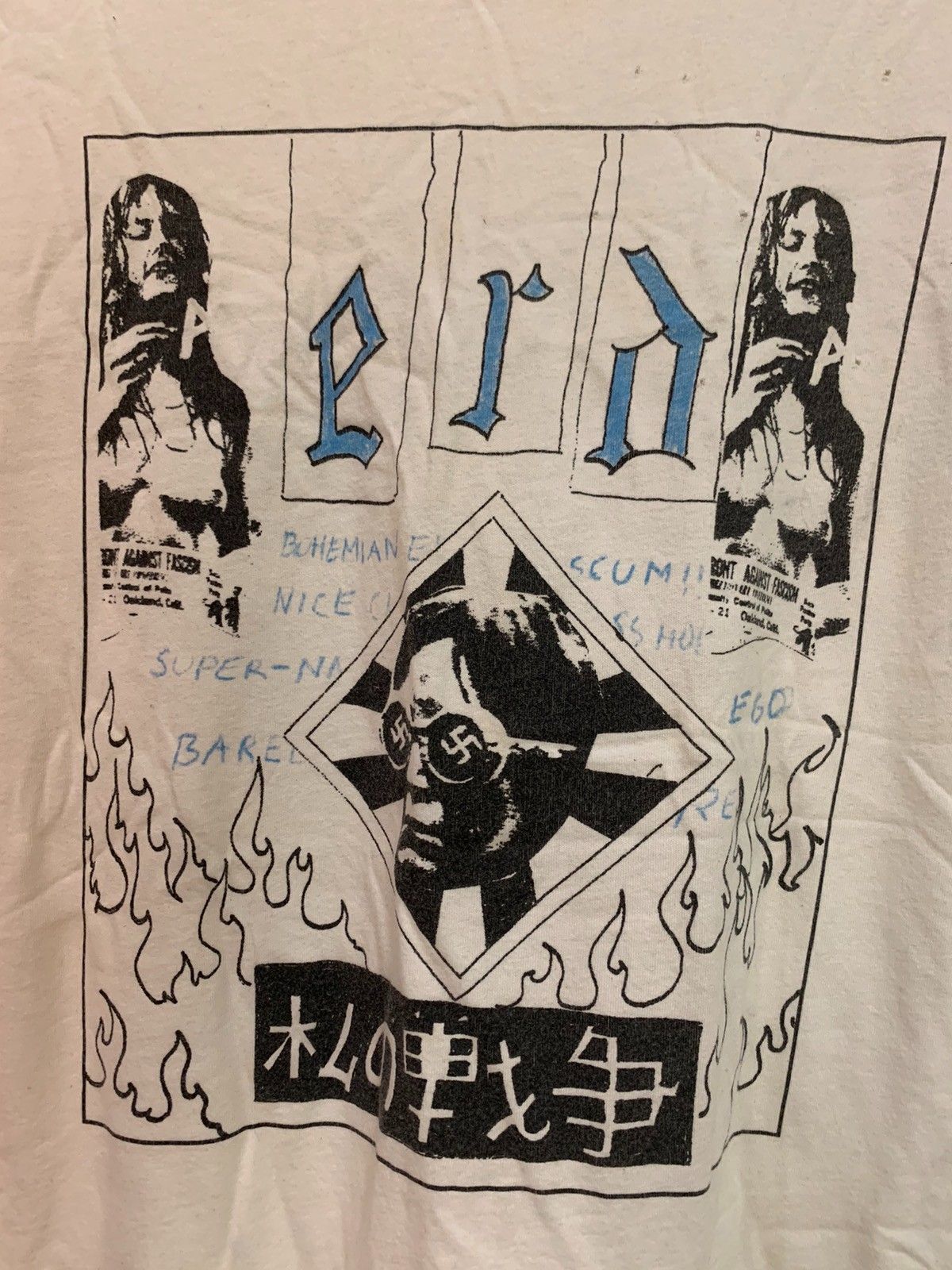

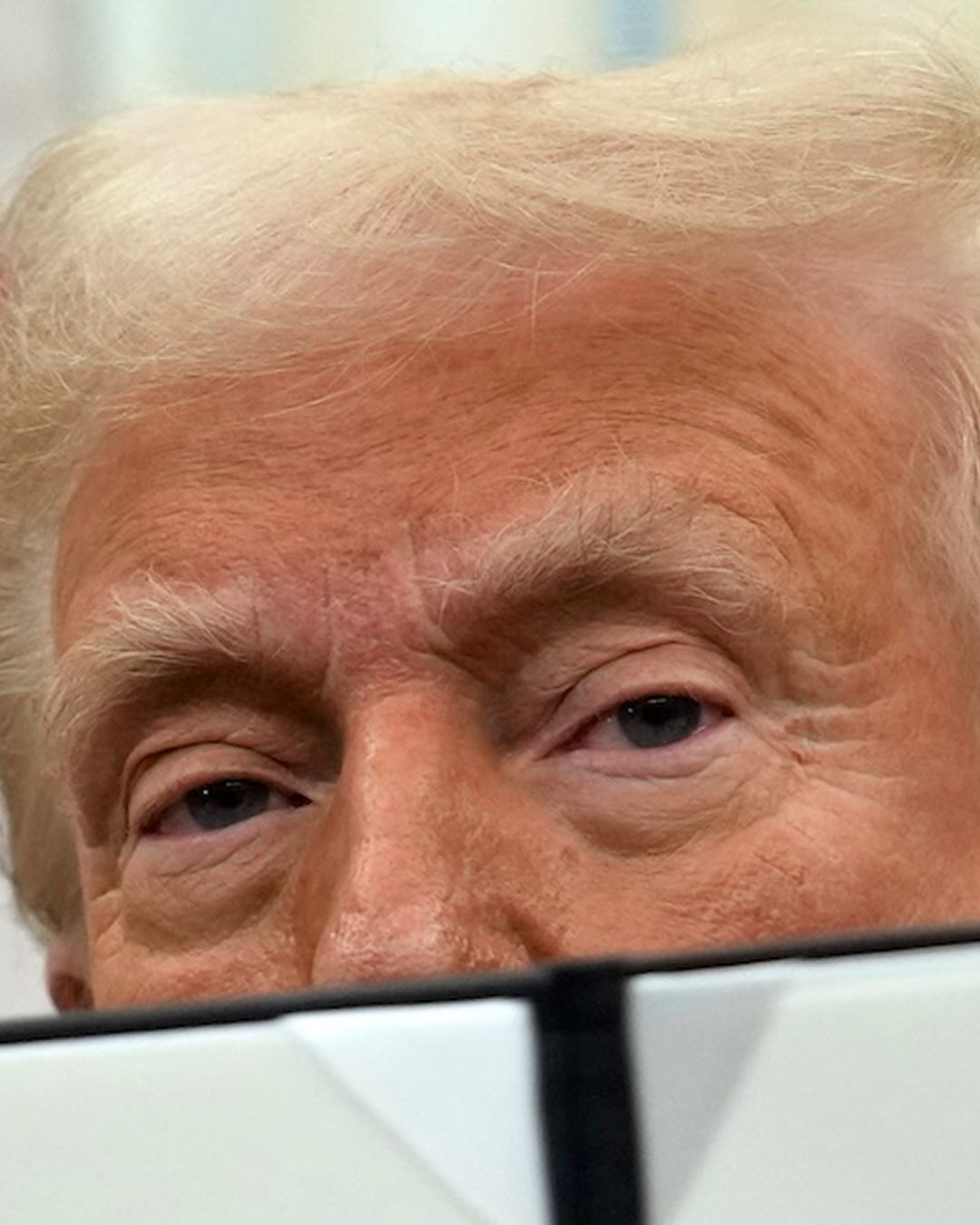

Looking at the specific case of Enfants Riches Deprimès, where the disconnect between image and ideology is most evident, one could easily point out how, in his pursuit of the outrageous and the piquant, Henry Levy has in the past plundered the political iconography of the ultra-right: the Nazi Iron Cross can be found in numerous ERD-produced garments in the past, as well as Donald Duck giving the Nazi salute and even the famous Swastika Flame t-shirt, which, though in tones of anti-fascist rebellion, has a swastika at its center-not to mention the occasional eagle or Brandenburg Gate. Specifically, Levy's decision to include iconography that recalls Nazism takes on another meaning considering that the designer and his family are Jewish (as Complex reports, Levy wrote on Facebook in 2016: «If I wasn't Jewish I would kill myself. Because I wouldn't be rich») and that in fact the tactic of shocking at all costs stems as much from its immersion of the meanderings of punk, a subculture that did not disdain playing with Nazi iconography, as in its pursuit of a «elitist, nihilist couture», as Levy himself told Complex. It would be interesting to know, now that Kanye has also stepped up his game with anti-Semitic-sounding tweets on Sunday night, what Levy's position is on political statements as entertainment and counterculture.

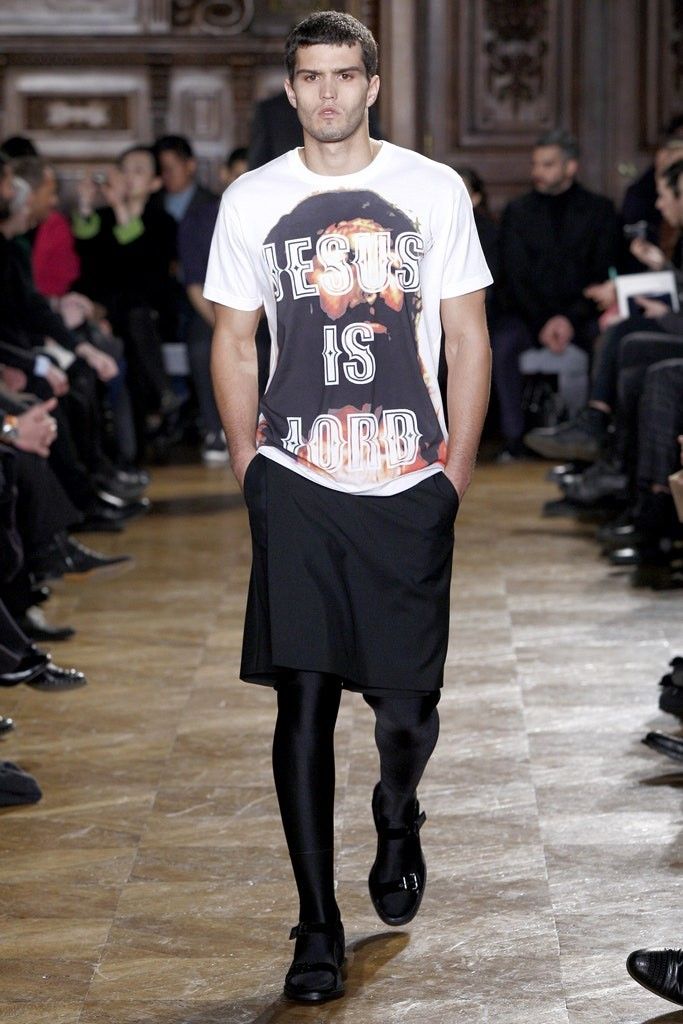

The bite and scratch of nihilism, in any case, emerges precisely in the brutal nonchalance with which references to the traumatic affair of Nazism are handled. The same is evidently true of the symbolism of Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party, which instead of referring to punk is probably a reference to the fascination with communism as a counterculture felt by New Wave filmmakers such as Godard, author of La Chinoise and Week End. In this case, it can be assumed that Maoist iconography should be interpreted as in the double sense of shock factor and a taste for the naïveté of certain commemorative prints of yesteryear - a souvenir taste. Precisely in the category of naïve souvenir taste would seem to place the front of Kanye's controversial shirt. The print-collage of John Paul II's face accompanied by a corny phrase in Spanish suggests not so much a personal devotion (Kanye claims to be a Christian but is not Catholic) as a desire to evoke religiosity by ironically wearing the "merch" of the main pop icon of Western Christianity. In some ways, the intention with which the t-shirt appears to have been worn is not overly distant from the "Jesus is Lord" shirt created for Givenchy's FW10 collection by Riccardo Tisci, who, by the way, is Kanye's friend and was at last Monday's show. It goes without saying that the question of the secularity of political icons of the past as, if you will pardon the term, "merch" is a two-sided issue. Just as Kanye's now infamous T-shirt had one acceptable side, the one with the graphic of the Pope, and one that was intolerable, so the political icon of the past is distant and safe enough to be worn and flaunted without a problem, while the statement too close to a burning present is something, precisely, intolerable.

@cyborgkiddd La Chinoise (1967)#lachinoise #filmtok #communism #marxism #jeanlucgoddard #viral #foryoupage #fyp #publicidade #edit som original - David Wmv

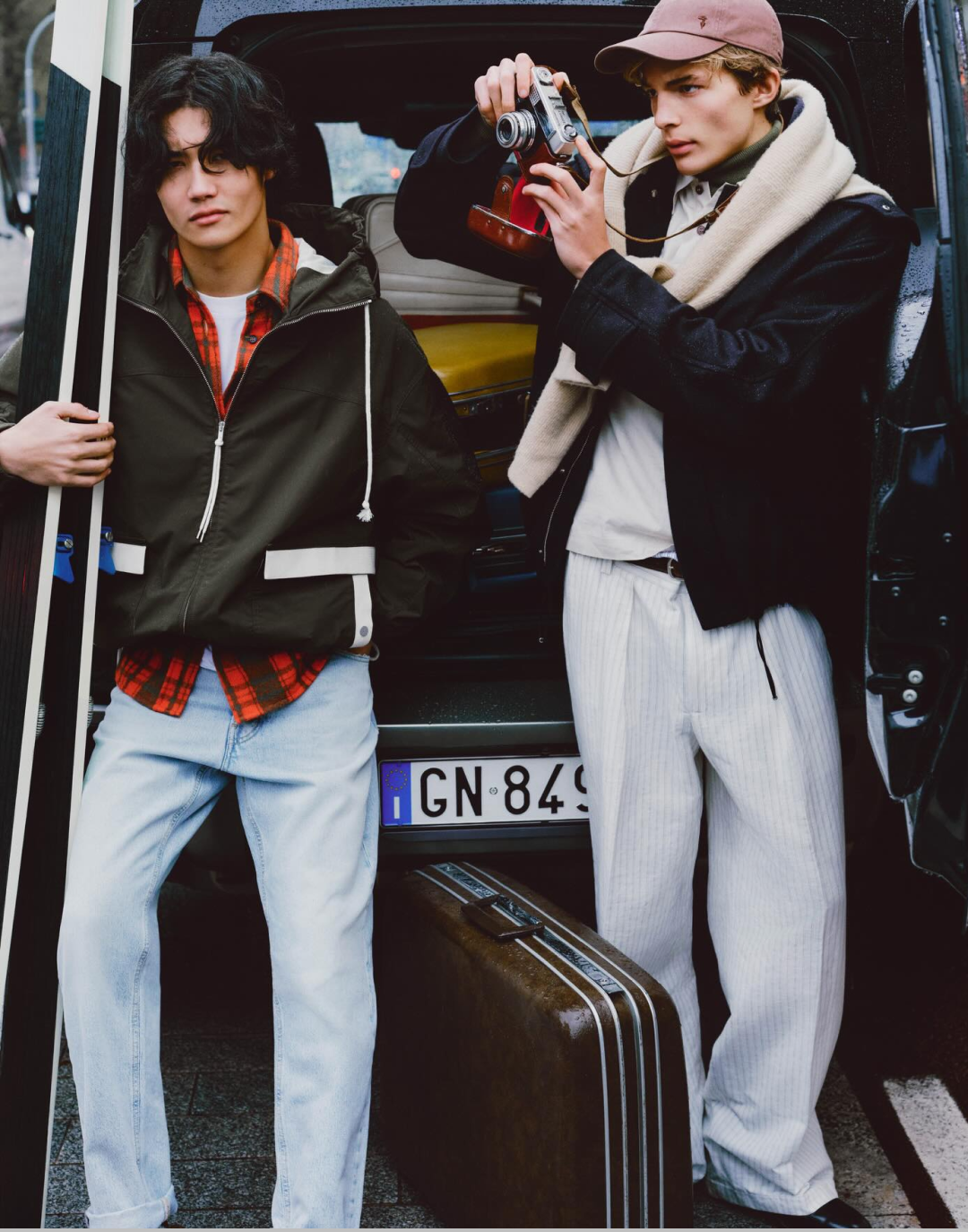

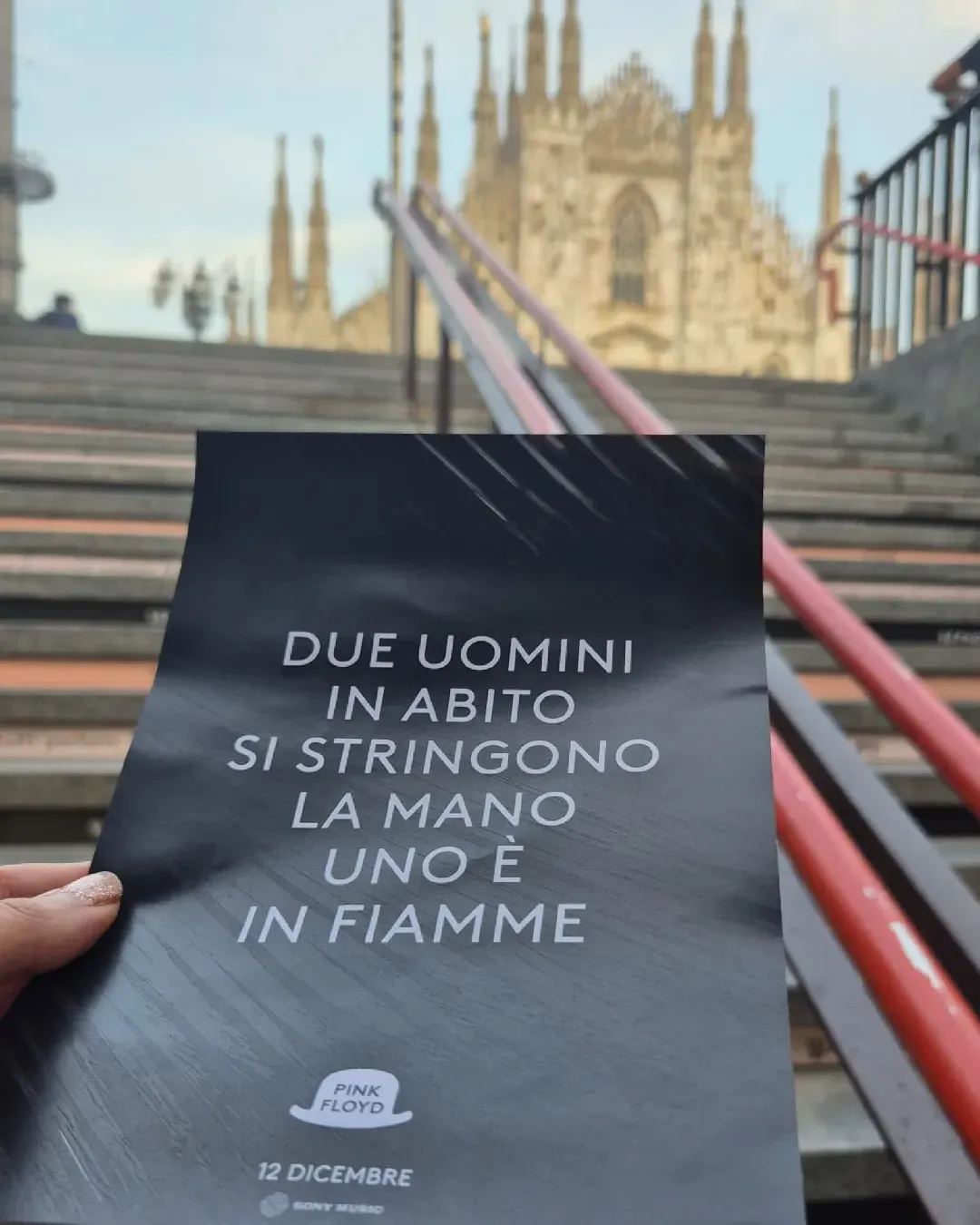

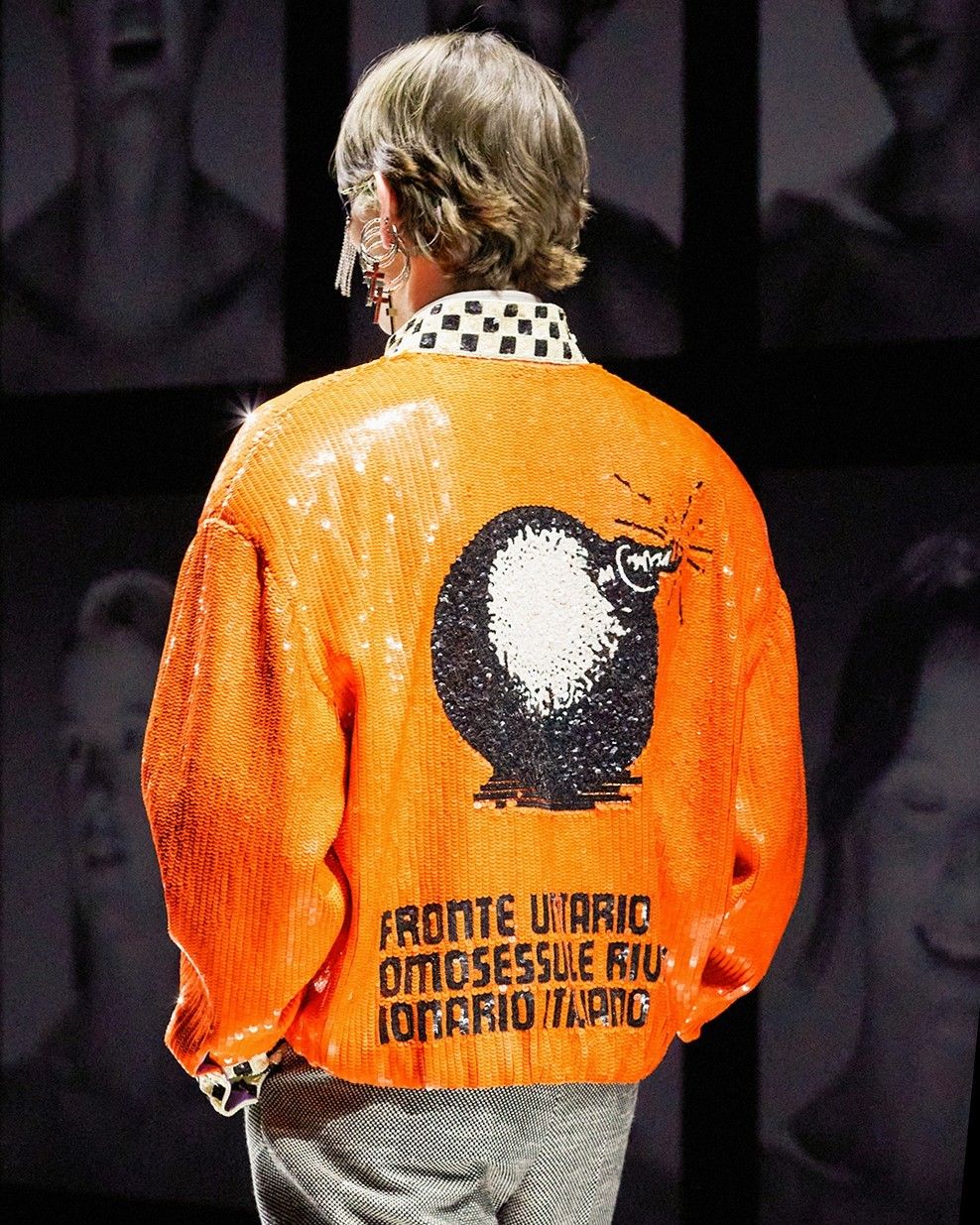

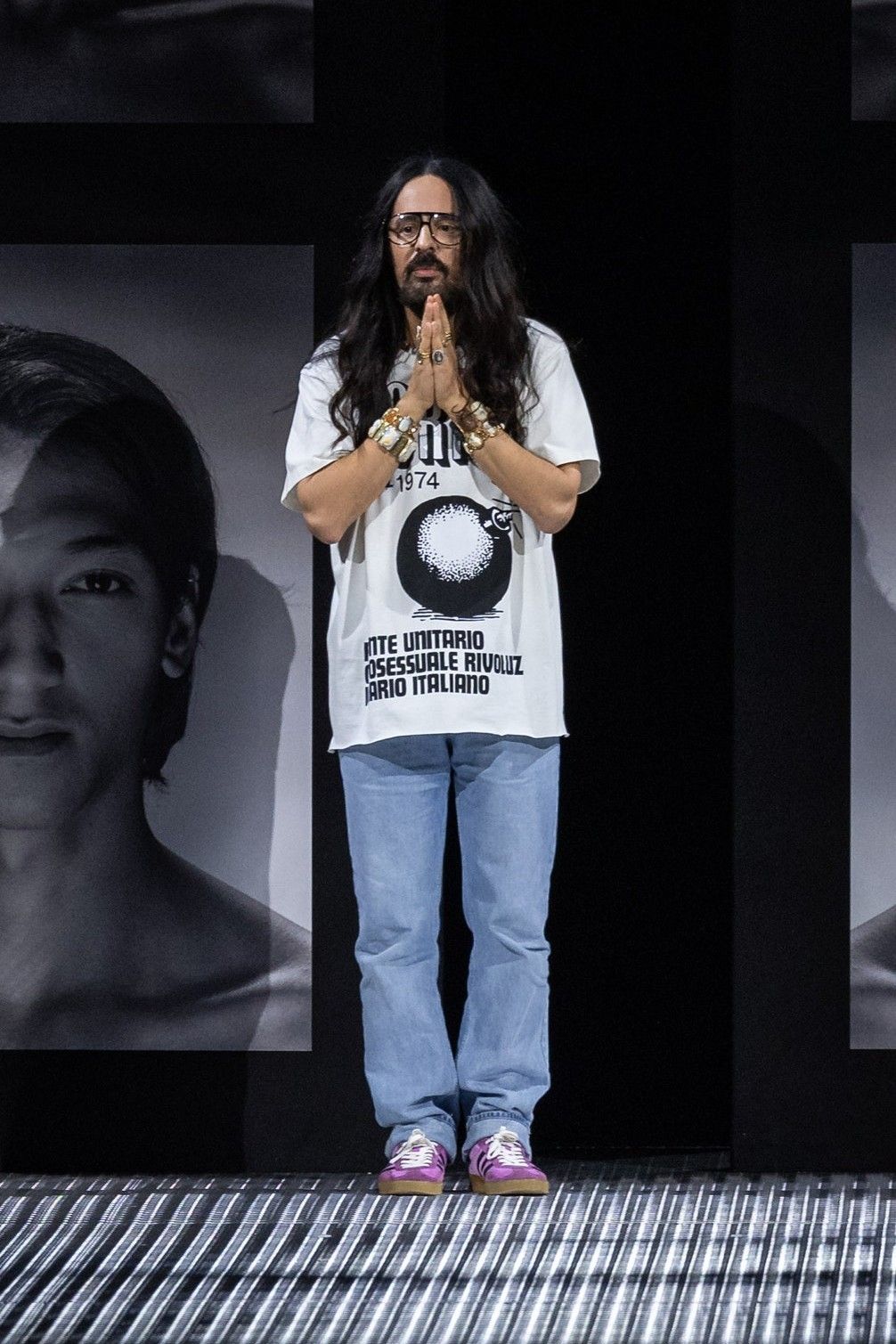

Also in Milan this season, Gucci has been frequenting politics with Alessandro Michele making F.U.O.R.I., an acronym for Fronte Unitario Omosessuale Rivoluzionario Italiano, a graphic used throughout the collection, appearing especially on a jacket and then worn by the creative director himself. It is clear, here, that the political statement invokes more unity, emphasizes the political clout of the LGBTQ+ community, and retrospectively celebrates the Italian homosexual liberation movement rather than emphasizing a designer's or brand's adherence to the Marxist ideals supported by the actual political group. In contrast to Enfants Riches Deprimès, the political statement in Gucci makes itself the bearer of those progressive values in the field of civil rights that Michele had already emphasized in the Cruise 2020 show with the "My Body My Choice" jacket, a slogan that by the way has also had echoes this season in the Stella McCartney, Imitation of Christ and Rentrayage lookbooks. While born with different senses, however, and while Gucci's slogans are more relevant to present political issues, both the presence of Mao Zedong on ERD's t-shirts and the presence of the FUORI! logo on Gucci's jackets refer either to a purely aestheticized past as in the case of ERD or to shareable inclusive values that can be applied to the present but remain universally valid. The slogan on the back of Kanye's T-shirt, on the other hand, unlike the images of John Paul II, does not speak of aestheticization or progressivism, but constitutes a provocation designed to divide and disunite. Even Vivienne Westwood's hyper-controversial "God Save the Queen" t-shirt even with its provocative and polemical tones was meant to celebrate a cultural heritage-though today perhaps, in the perspective of a post-colonial society, that same t-shirt could be loaded with unforeseen and potentially offensive connotations.

Since the global explosion of Black Lives Matter, with the rise of online activism (performative or otherwise) but also with the rise of far-right movements such as those of Donald Trump's supporters, the self-expression promised by fashion has become an area increasingly receptive to the stances of politics. Ideology is worn, reduced to slogans (who remembers Cara Delevigne's "Peg the Patriarchy" and Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez's "Tax the Rich" at the Met Gala 2021?) and becomes a manifestation of a society whose political conceptions become increasingly polarized and extreme, and where adherence to one of the two currents becomes characterizing even on the level of clothing: think of MAGA hats, t-shirts with rifles and eagles, and all those non-verbal codes that testify to this or that affiliation. But at the same time, the public's levels of disillusionment and cynicism with politics and its fundamental hypocrisy challenge those same ideologies. And what happens when, ideology gone, the taste for political statement persists? Mao Zedong and John Paul II, but also churchcore crosses, become decorations detached from their historical significance, for example, and become easy to flatten into the two-dimensionality (and in some ways banality) of an icon. But the same process of trivializing and zeroing in on ideological meanings makes it all in all superfluous to turn a political figure into a graphic for a T-shirt: both because there is no political figure so commendable as to be devoid of historical and personal shadows, and because the aestheticization of an icon is often antithetical to the values promoted by that icon, and because reducing a political symbol to decoration means, precisely, misrepresenting it always and in any case. Can fashion take this risk? Or, better yet, should it?