Hello London #9 - Tate Modern Switch House Your first look at the new pyramid building

Tate Modern's one of those museums in London you immediately feel attached to, and where one never gets tired to return.

Founded in 2000 and born from the ashes of the old Bankside Power Station, during the past sixteen years, Tate has been elevated to the status of a quintessential European Mecca for contemporary art lovers and self-declared creatives alike. Placed on that path that stretches from London Bridge to the London Eye, squeezed between the Millennium Bridge and the street food chains' block, the Turbine Hall is located in a spot which is probably London's most touristic yet most charming and evocative, and, with a full programme of exhibitions, screenings and events, Tate remains a good shelter on rainy days, a place to get lost for hours, be inspired and buy art books.

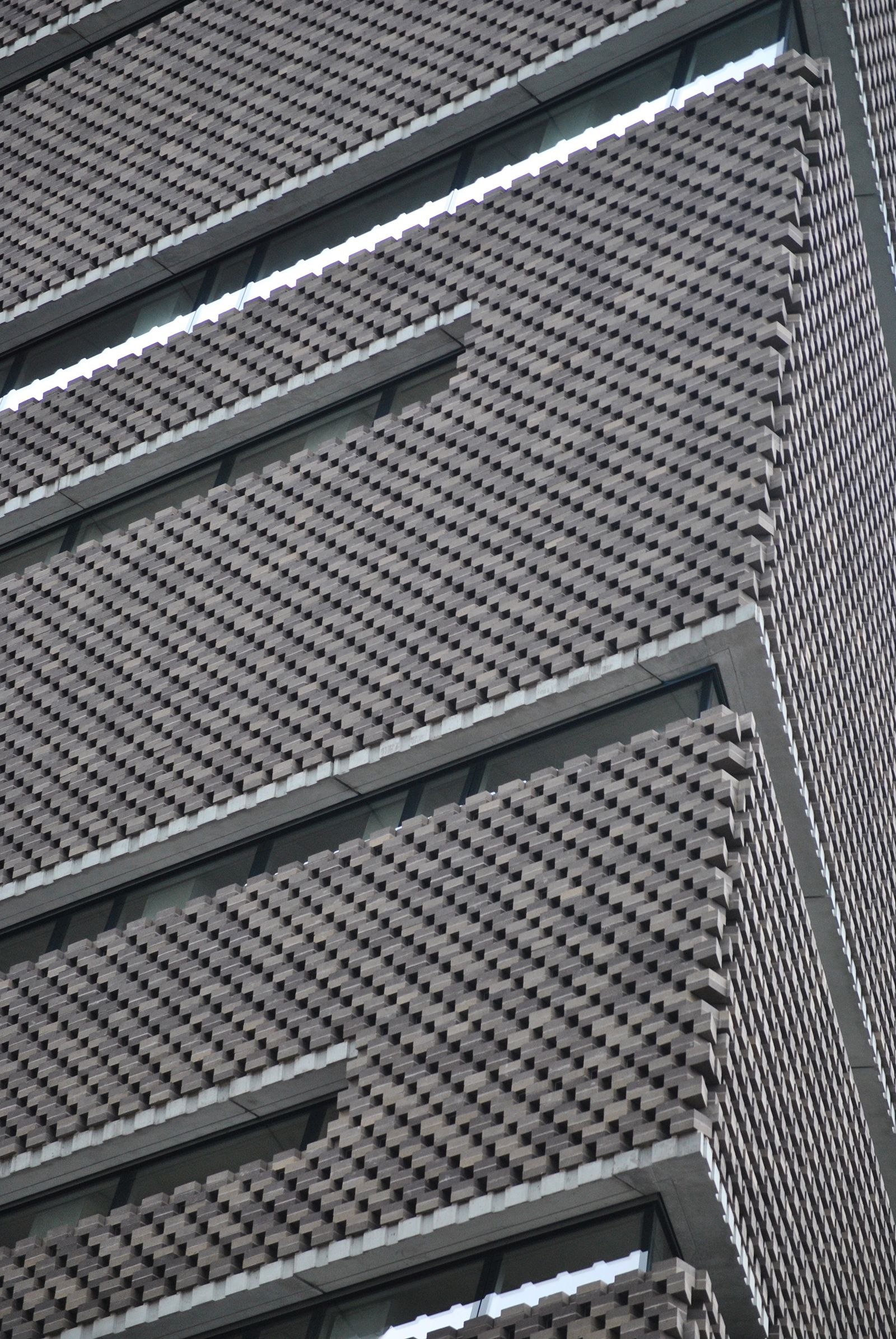

In short, we all love the Tate. And probably after this weekend, we will even be wanting to move there straight away. Last Friday, in fact, the gallery's new wing, the Switch House, a modern ziggurat twisting on itself designed by Herzog & de Meuron, has finally been revealed.

Seen from outside, the brick pyramid can generate the most conflicting opinions, on a scale ranging from 'exquisitely postmodern' to 'so retro-futuristic to seem past before even existing', a Swiss re-interpretation of that post-war rationalist architecture that's not so avant-garde but that these days we seem to like so much, and that's well harmonising with the previous building. To make it up for it, however, once you cross the threshold, the new Tate is so beautiful that it will make you forget everything else.

With its huge surface, the Switch House spans through ten floors, the area of which gets slightly smaller and smaller as you go up, the plays of curves creating unexpected intersections.

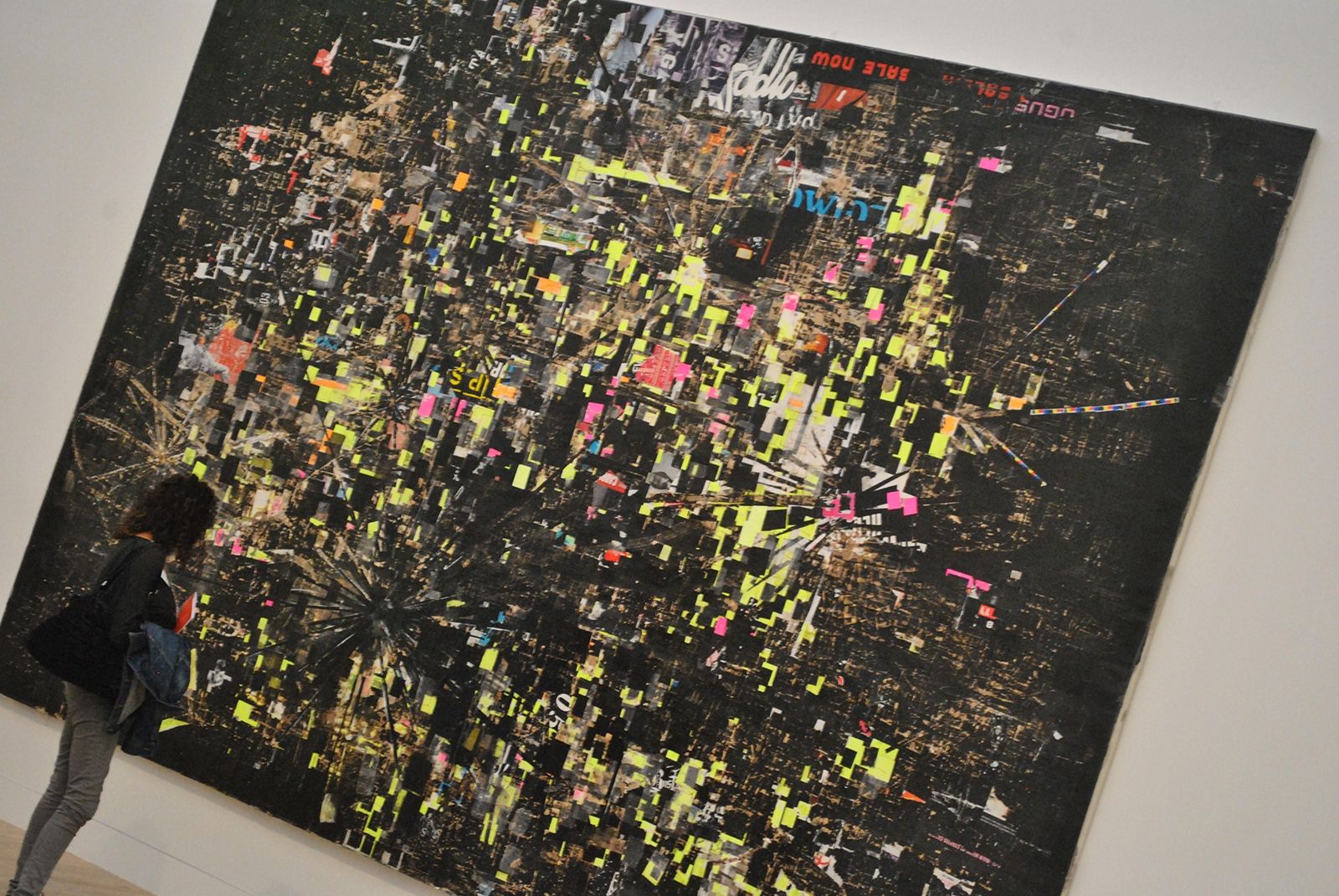

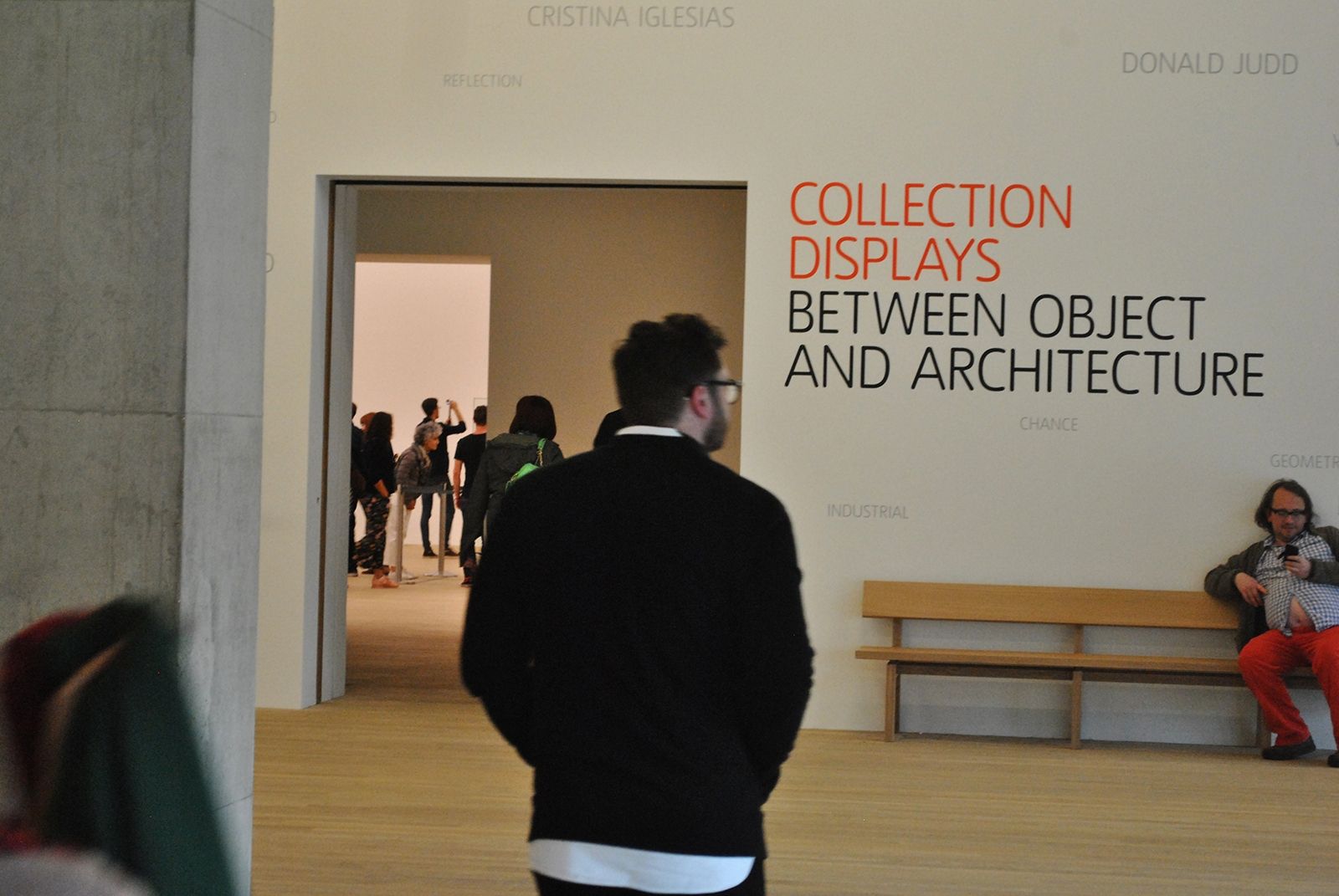

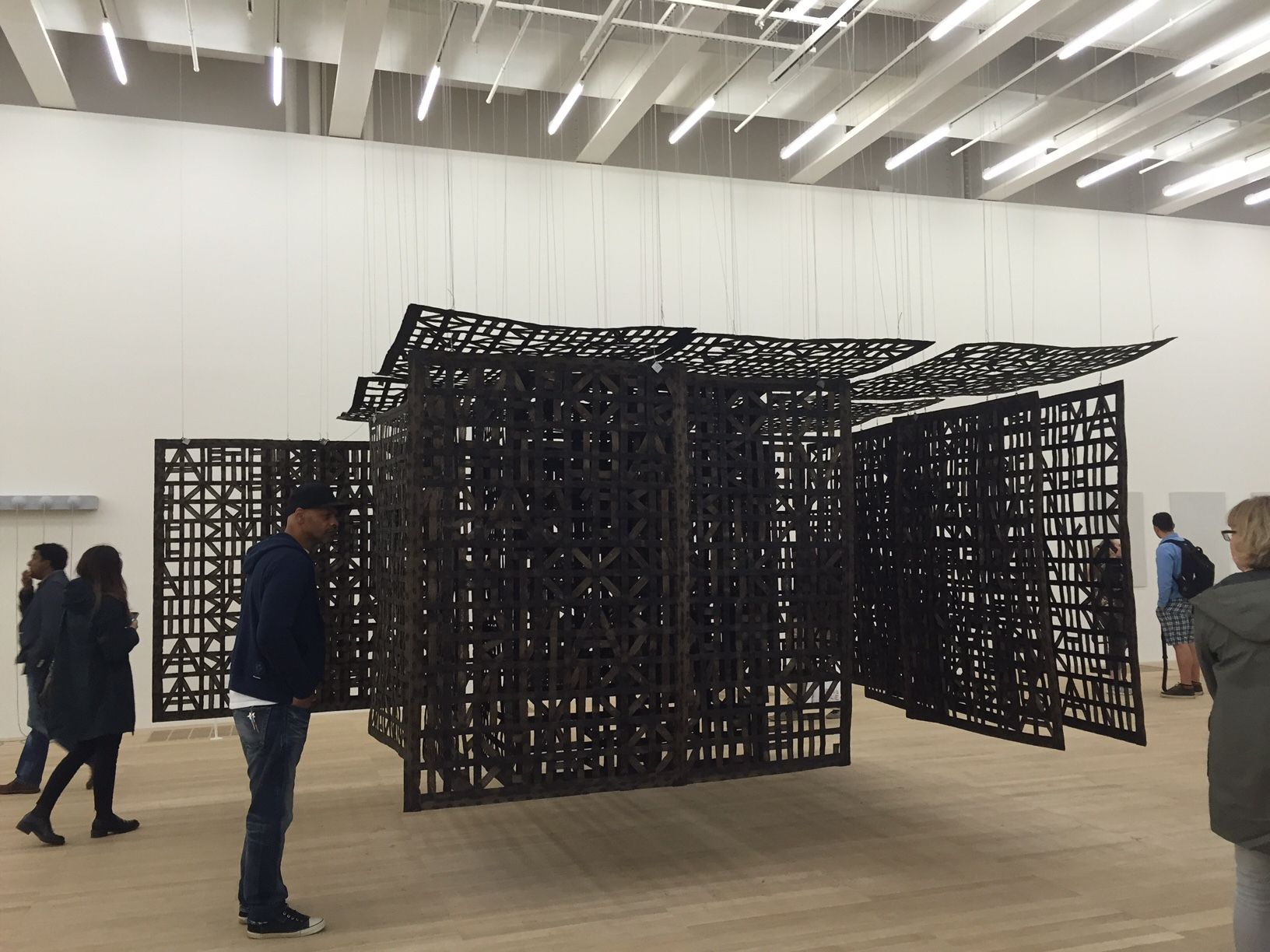

Our tour obviously starts from the first floor, which winds through two large rooms that comprise works recalling the ideas of space, architecture, science and experimentation with different materials. There's Yayoi Kusama's magic box covered with mirrors in and out (The Passing Winter), which, thanks to rounded holes that allow you to see it from the inside, gives us the illusion of being catapulted into one of the beautiful Japanese artist's mirrored-rooms; the open-ended space created out of crisscrossed steel strips by Cristina Iglesias (Pavilion Suspended in a Room); the bubbles-generating tube by David Medalla (Cloud Canyons No.3: An Ensemble of Bubble Machines); the geometric structure made out of random objects and scraps by Tony Cragg (Stack) which makes us reflect on man's impact on the landscape; the pink glass cube by Roni Horn (Pink Tons), the highly levigated top surface of which creates unexpected light reflections and constantly changing colours, simulating a water surface.

Passing through a 'chill-out zone' featuring steel cages (Capsules by Ricardo Basbaum) – in which some visitors were comfortably lying, whether just resting or playing with their phones –, we get to the next level, which among the others documents visionary German artist Rebecca Horn's body-extensions, a series of 'wearable sculptures' creating unsettling yet fascinating dehumanised figures.

The next floor is almost entirely occupied by the installation Women and Work, the result of an interesting socio-political study on the conditions of women employed at the Metal Box Company factory in Bermondsey, south London, carried out between '73 and '75 by Margaret Harrison, Kay Hunt and Mary Kelly and merged into a valuable collection of interviews, documents, videos, and statistics.

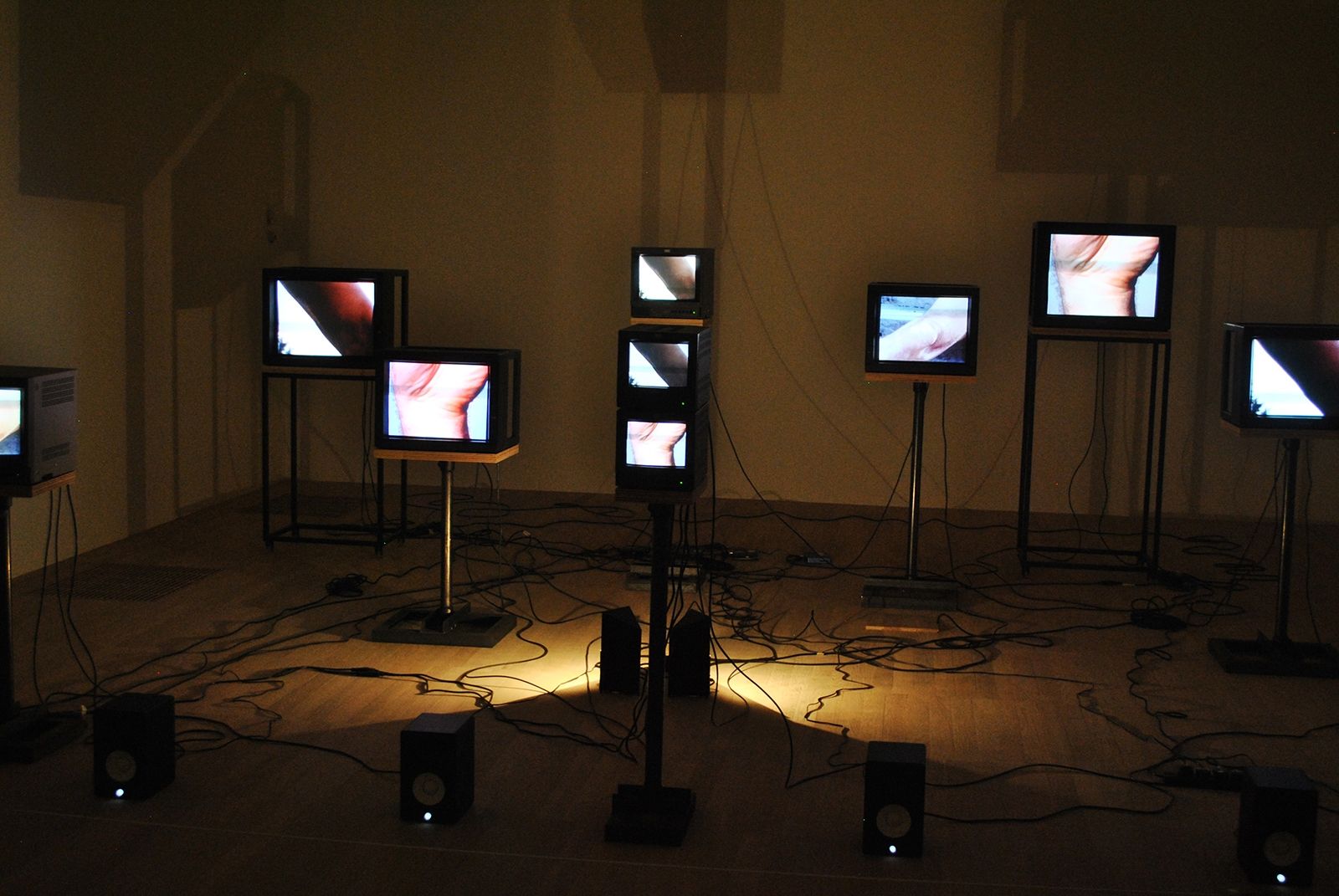

At this level, we can also find the screening of Daria Martin's Birds, a surreal video combining performance, music, sculpture and film in order to create what the artist has called 'total artwork'; and Rhythm, a long table showcasing all the 72 objects (including the famous gun) that Marina Abramovic gave to the public to use on her during her 1974 performance in Naples, I am the object.

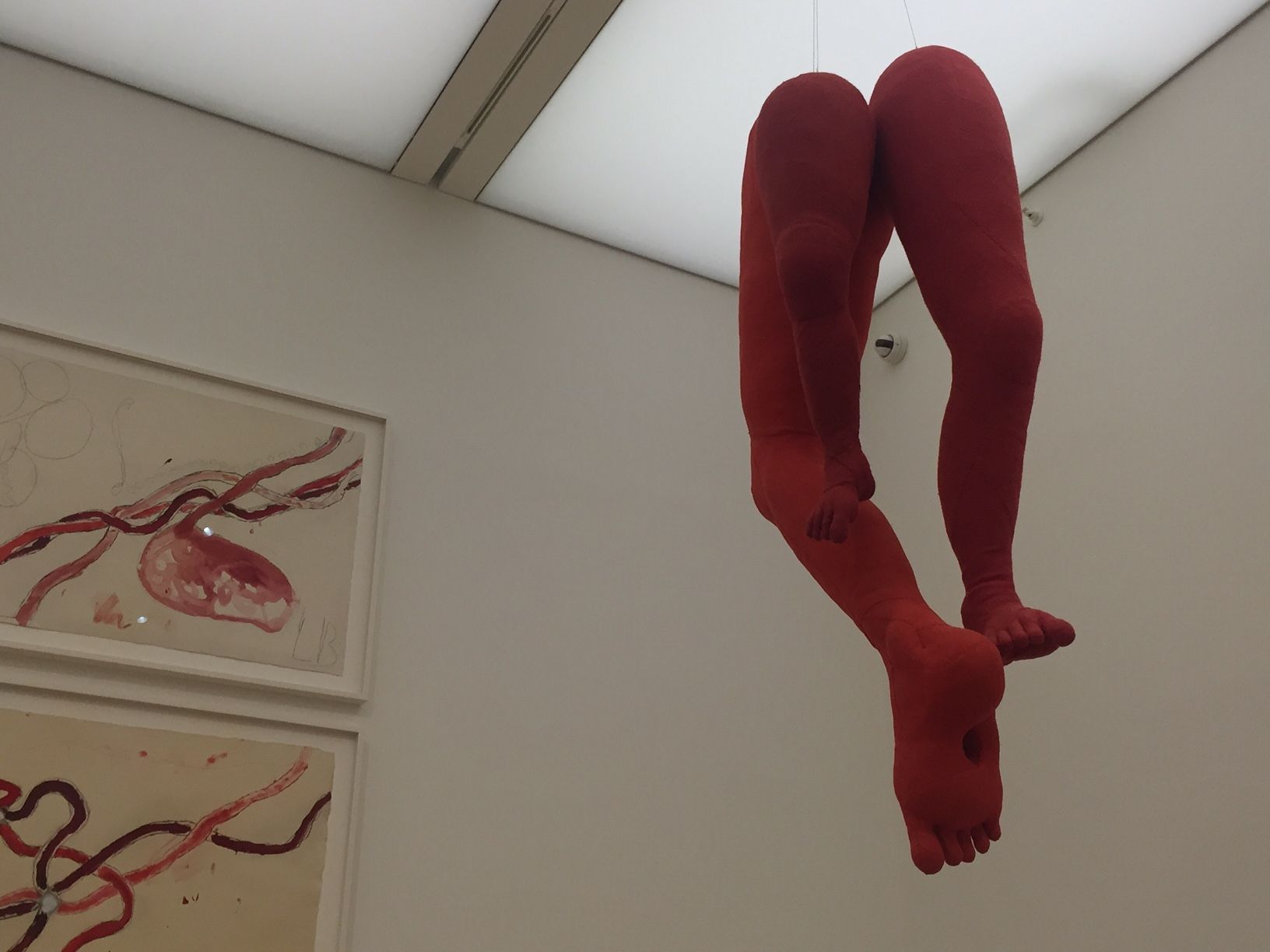

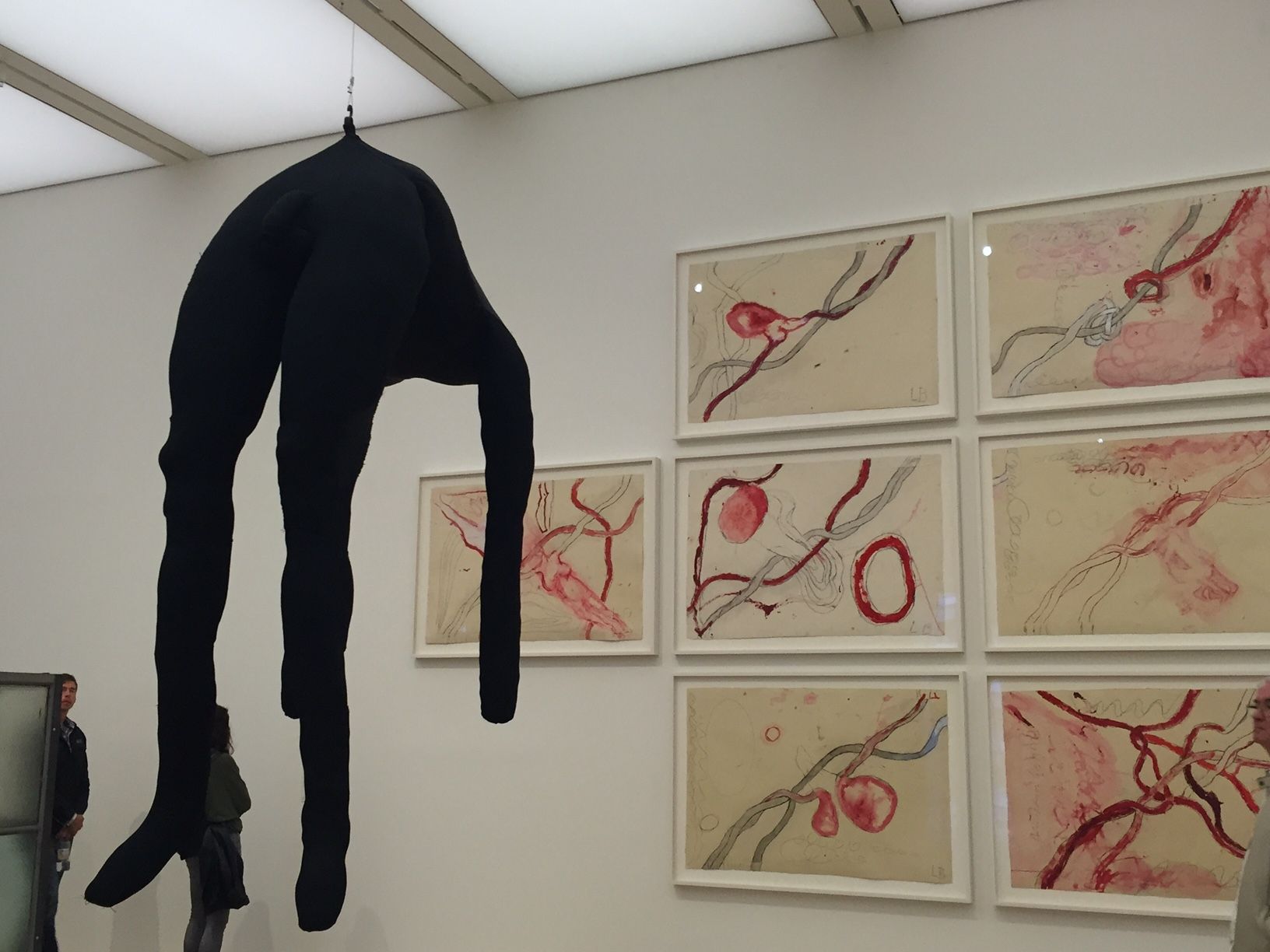

The fourth floor, one of the most engaging, is entirely dedicated to French artist Louise Bourgeois' works. Among puppets with human features and legs hanging from the ceiling, mirror sculptures pointing at the theme of voyeurism, blood-streamed paintings of hands losing and finding each others again and sculptures of deformed faces, we are led to discover the subject matters dear to the artist, on a journey through the most primordial human emotions (from love to loss and fear), in a compelling mix of grotesque and pleasant to the eye.

Finally, the new Tate is a space designed to hang out, to sit on the windows' cornices with a cup of tea and enjoy the view of the Shard dissolving within mantles of fog, to watch a movie crouched down in a cage – a really comfortable one, complete with a mattress –, to bring your folding stool around until you decide in front of which artwork you wanna settle, to look at art while feeling at home.