Swatch patronage at the Venice Biennale We visited the brand's pavilion among emerging artists and a 15-meter diorama

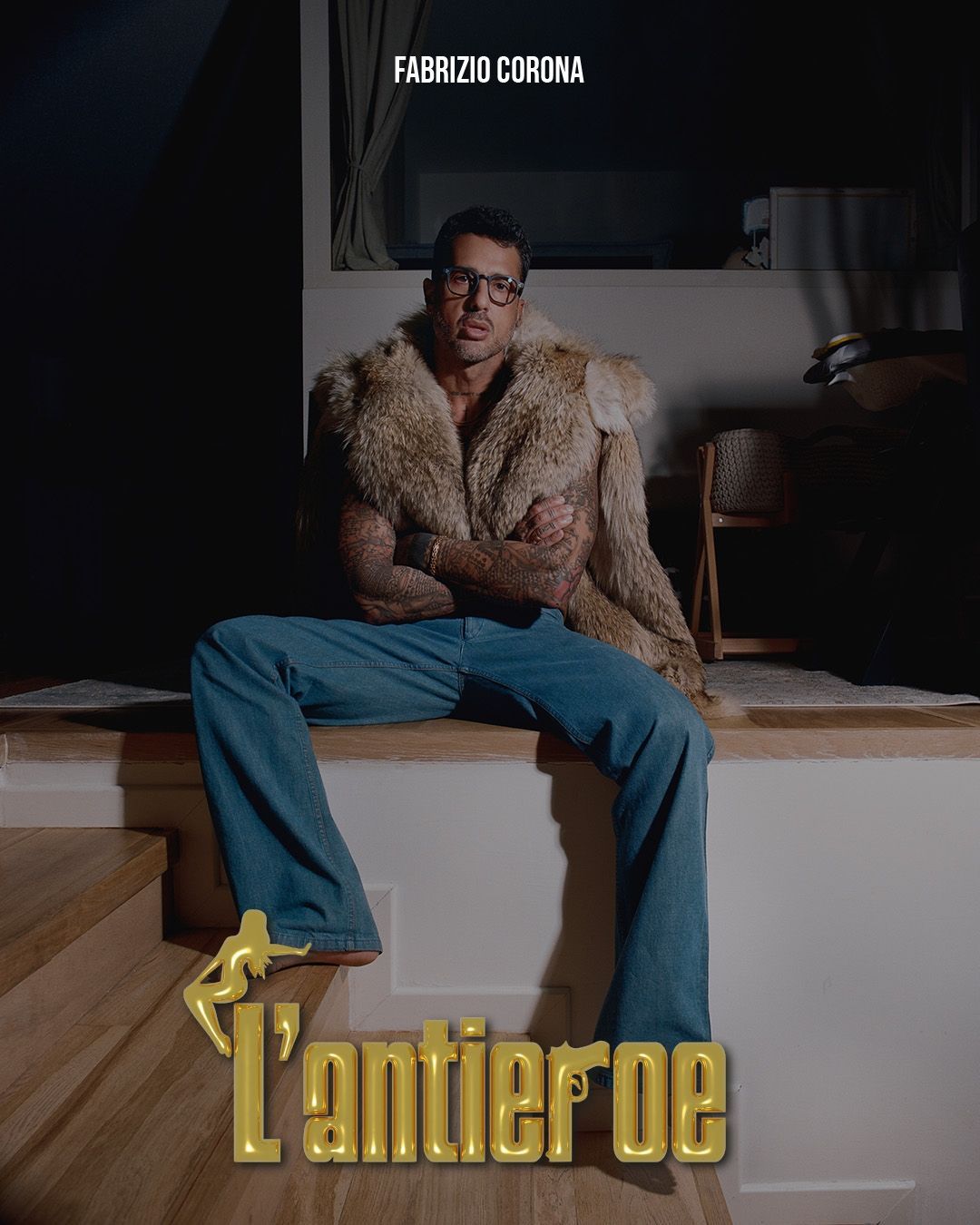

Venice is beautiful, at least until you realise you're seasick. And yet if there is a valid deterrent to endure the nausea caused by an agitated sea on a rainy day when your ferry sways towards the sky as if it wanted to touch it, it is the Venice Biennale, the first curated by a woman in a hundred years of history, Cecilia Alemani. On the occasion of the most eagerly awaited European event in the field of international contemporary art and in what is, logistical problems aside, the most romantic city in the world, Swatch presented its pavilion, a patronage operation that the brand has been carrying out since 2011 by selecting and inviting established or emerging artists to exhibit in the spaces of the Serenissima. In the last six editions of the Biennale, the Swiss watch brand has been one of the main supporters, as well as being, as the president of the event himself, Roberto Cicutto, "a creator and encourager of art". This year, after having brought names such as Joe Tilson and Ian Devemport to the lagoon, a special pavilion will host the works of five selected artists, while next door, in the Giardini, a mammoth work will tell Venice from an entirely new point of view.

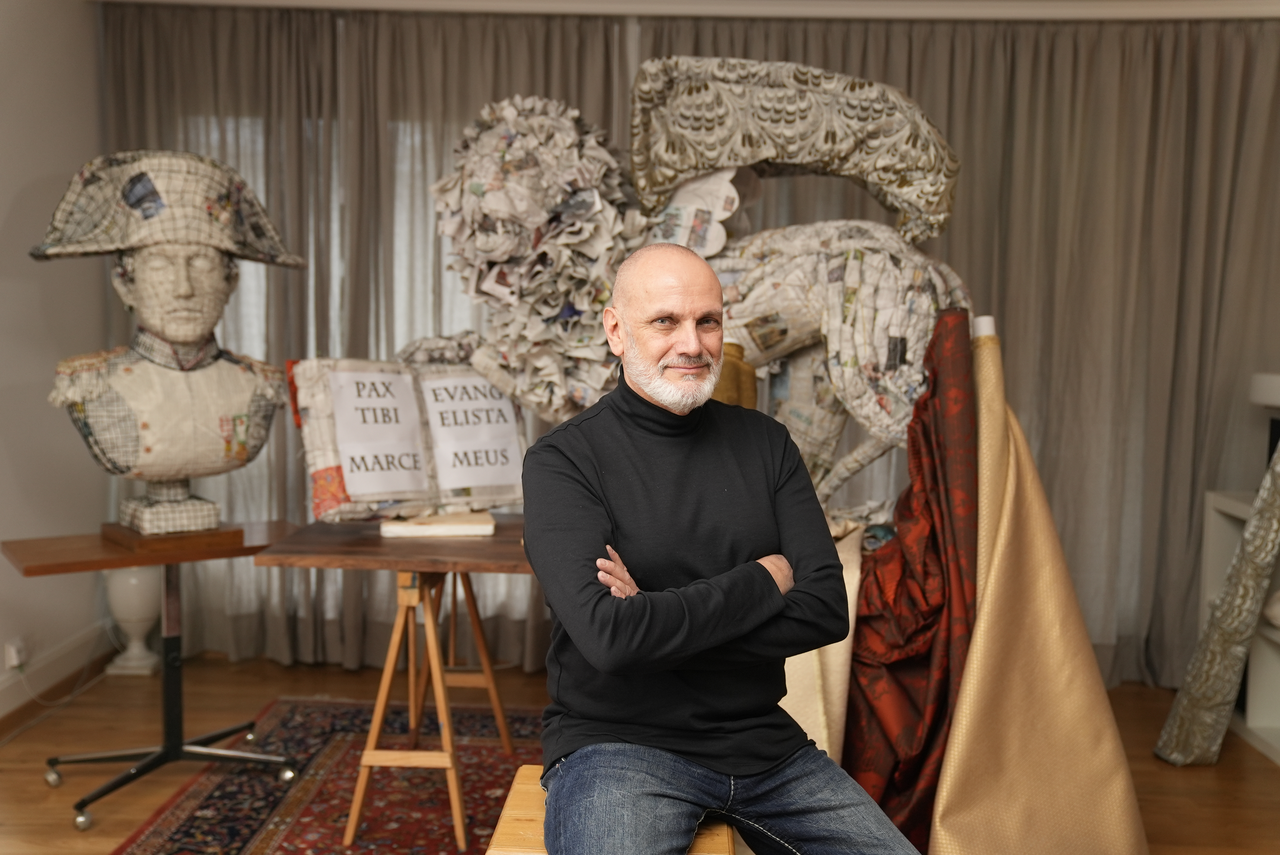

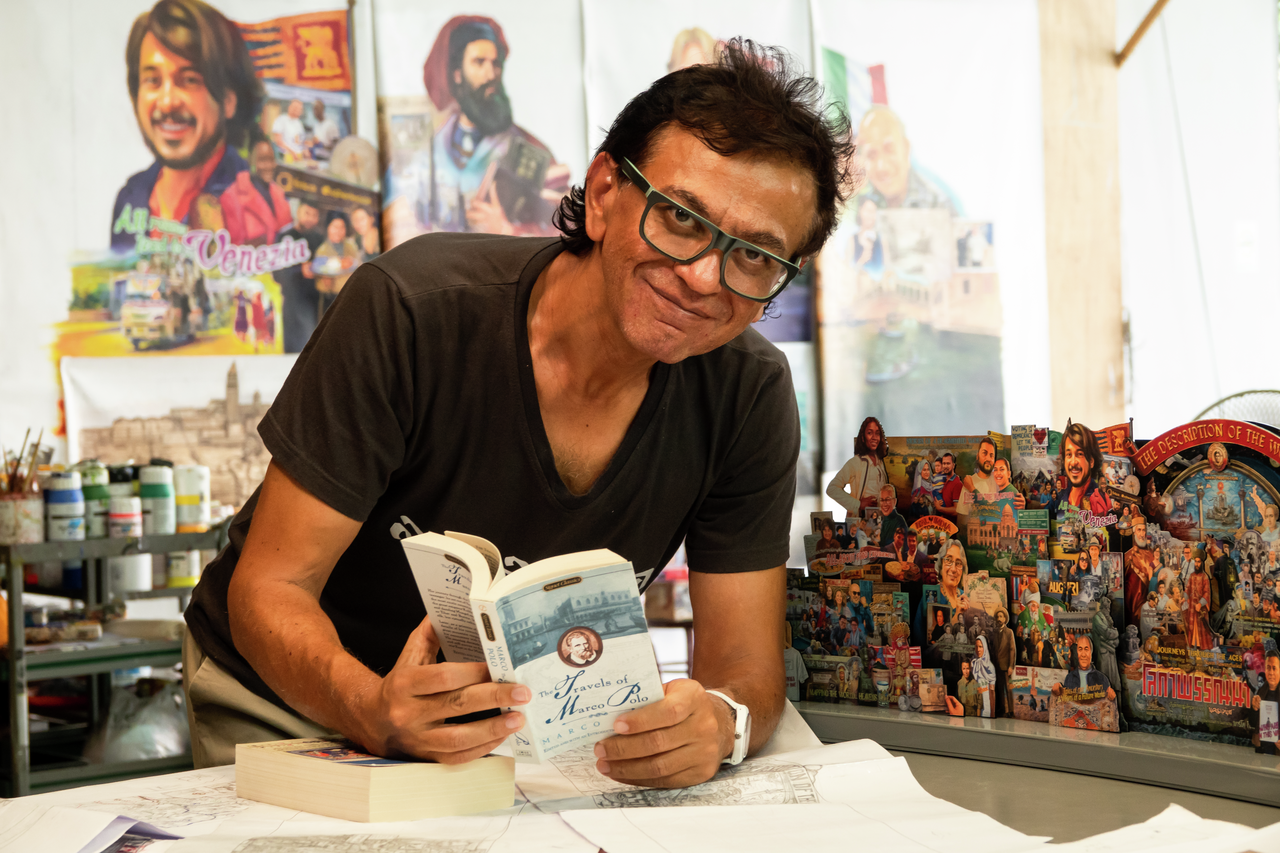

There was Marcelot, the Swiss-Brazilian artist who, armed only with sheets of newspaper and string, created two sculptures that were both celebratory and provocative: the lion symbol of the city and the bust of Napoleon, its historic adversary - «I moved my office into my room to finish everything in time», he says. There was Navin Rawanchaikul, who, interviewed by Carlo Giordanetti, a leading figure in Swatch management and CEO of the Art Peace Hotel in Shanghai where the brand hosts artists from all over the world, talked about how and to what extent his work speaks of "identity". One of Asia's leading international artists who had already exhibited in Rome at MAXXi in 2021, where Giordanetti had first appreciated him, on the occasion of his first visit to Venice, in the midst of the pandemic, studied Marco Polo's "Il Milione", with which he almost felt he had swapped places (from Italy to Asia he and centuries later from Asia to Italy Navim) and observed how the city has always been a melting pot of exchanges and migrants: Africans, Bengalis, Pakistanis who came to the city to build a new life for themselves. The result is a mega diorama, measuring 15 metres by 4, in which all the characters emerge in 3D, telling their stories of migrants alongside local stories, of locals born and raised in the same canals, and how these very different realities manage to blend together in a city so full of tourists that residents go unnoticed. In the kaleodoscopic collage, Marco Polo is an ever-present feature, and Navin even wrote him a letter thanking him for his wonderful story, so much so that it is from the original name of Il Milione that he give the title to his work 'The description of the world'. The other three artists, on the other hand, tell of fantastic worlds, works that speak of escape in a historical period in which reality seems to be a nightmare from which to flee. The answer seems to lie in abstractionism, surrealism and, at times, in the past: Hoyoon Shin's resin and paper Buddhas, Xue Fei's cartoon characters, Tang Shu's pandemic symbolism, Landi's abstract and childlike forms.

Looking at a work of art is a very personal experience: the history, cultural heritage and ideology of each person clash with the artist's thought, which is not always explicit, sometimes embracing it, sometimes rejecting it. But when it is the artist who explains how that same thought reaches a material support, it is completely a different story: from Navim at dinner, who explains that his T-shirt bears the Indian name of his mother's city of origin, to Marcelot, who walks alongside you while visiting the Biennale in broken English and a warm smile. After all, isn't that what art is all about? The passage of an emotion imprinted in time, so that it can last perhaps forever, a bit like memories. Well, those of that Venetian weekend were very good.